Delhi Law Review Students Edition, Volume:V(2016-17)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Legislative Assembly of Bihar

STATISTICAL REPORT ON GENERAL ELECTION, 1990 TO THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF BIHAR ELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA NEW DELHI Election Commission of India – General Elections, 1990 to the Legislative Assembly of Bihar STATISTICAL REPORT CONTENTS SUBJECT Page No. 1. List of Participating Political Parties and Abbreviations 1 - 2 2. Other Abbreviations in the Report 3 3. Highlights 4 4. List of Successful Candidates 5 - 12 5. Performance of Political Parties 13 -14 6. Electors Data Summary – Summary on Electors, voters 15 Votes Polled and Polling Stations 7. Woman Candidates 16 - 23 8. Constituency Data Summary 24 - 347 9. Detailed Result 348 - 496 Election Commission of India-State Elections, 1990 to the Legislative Assembly of BIHAR LIST OF PARTICIPATING POLITICAL PARTIES PARTYTYPE ABBREVIATION PARTY NATIONAL PARTIES 1 . BJP BHARTIYA JANATA PARTY 2 . CPI COMMUNIST PARTY OF INDIA 3 . CPM COMMUNIST PARTY OF INDIA (MARXIST) 4 . ICS(SCS) INDIAN CONGRESS (SOCIALIST-SARAT CHANDRA SINHA) 5 . INC INDIAN NATIONAL CONGRESS 6 . JD JANATA DAL 7 . JNP(JP) JANATA PARTY (JP) 8 . LKD(B) LOK DAL (B) STATE PARTIES 9 . BSP BAHUJAN SAMAJ PARTY 10 . FBL ALL INDIA FORWARD BLOC 11 . IML INDIAN UNION MUSLIM LEAGUE 12 . JMM JHARKHAND MUKTI MORCHA 13 . MUL MUSLIM LEAGUE REGISTERED(Unrecognised ) PARTIES 14 . ABSP AKHIL BAHARTIYA SOCIALIST PARTY 15 . AMB AMRA BANGALEE 16 . AVM ANTHARRASTRIYA ABHIMANYU VICHAR MANCH 17 . AZP AZAD PARTY 18 . BBP BHARATIYA BACKWARD PARTY 19 . BDC BHARAT DESHAM CONGRESS 20 . BJS AKHIL BHARATIYA JANA SANGH 21 . BKUS BHARATIYA KRISHI UDYOG SANGH 22 . CPI(ML) COMMUNIST PARTY OF INDIA (MARXIST-LENINIST) 23 . DBM AKHIL BHARATIYA DESH BHAKT MORCHA 24 . -

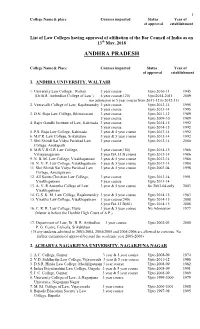

List of Law Colleges Having Deemed / Permanent / Temporary Approval Of

1 College Name & place Courses imparted Status Year of of approval establishment List of Law Colleges having approval of affiliation of the Bar Council of India as on 13th May, 2018 ANDHRA PRADESH College Name & Place Courses imparted Status Year of of approval establishment 1. ANDHRA UNIVERSITY, WALTAIR 1. University Law College , Waltair 3 year course Upto 2010-11 1945 (Dr.B.R. Ambedkar College of Law ) 5 year course(120) Upto2014-2015 2009 (no admission in 5 year course from 2011-12 to 2012-13) 2. Veeravalli College of Law, Rajahmundry 3 year course Upto 2013-14 1995 5 year course Upto 2013-14 1995 3. D.N. Raju Law College, Bhimavaram 3 year course Upto 2011-12 1989 5 year course Upto 2009-10 1989 4. Rajiv Gandhi Institute of Law, Kakinada 3 year course Upto 2014-15 1992 5 year course Upto 2014-15 1992 5. P.S. Raju Law College, Kakinada 3 year & 5 year course Upto 2013-14 1992 6. M.P.R. Law College, Srikakulam 3 year & 5 year course Upto 2013-14 1992 7. Shri Shiridi Sai Vidya Parishad Law 3 year course Upto 2013-14 2000 College, Anakapalli 8. M.R.V.R.G.R Law College, 3 year course(180) Upto 2014-15 1986 Viziayanagaram 5 year BA.LLB course Upto 2013-14 1986 9. N. B. M. Law College, Visakhapatnam 3 year & 5 year course Upto 2013-14 1986 10. N. V. P. Law College, Visakhapatnam 3 year & 5 year course Upto 2013-14 1980 11. Shri Shiridi Sai Vidya Parishad Law 3 year & 5 year course Upto 2003-04 1998 College, Amalapuram 12. -

1957 to the Legislative Assembly of Bihar

STATISTICAL REPORT ON GENERAL ELECTION, 1957 TO THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF BIHAR ELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA NEW DELHI Election Commission of India - General Election, 1957 to the Legislative Assembly of Bihar STATISTICAL REPORT CONTENTS SUBJECT Page no. 1. List of Participating Political Parties and Abbreviation 1 2. Other Abbreviations in the Report 2 3. Highlights 3 4. List of Successful Candidates 4 – 12 5. Performance of Political Parties 12 6. Electors Data Summary – Summary on Electors, voters votes Polled and Polling Stations 13 7. Women Candidates 14 - 16 8. Constituency Data Summary 17- 280 9. Detailed Result 281 - 330 Election Commission of India-State Elections,1957 to the Legislative Assembly of Bihar LIST OF PARTICIPATING POLITICAL PARTIES PARTYTYPE ABBREVIATION PARTY NATIONAL PARTIES 1 . BJS ALL INDIA BHARTIYA JAN SANGH 2 . CPI COMMUNIST PARTY OF INDIA 3 . INC INDIAN NATIONAL CONGRESS 4 . PSP PRAJA SOCIALIST PARTY STATE PARTIES 5 . CNPSPJP JANATA 6 . JHP JHARKHAND PARTY INDEPENDENTS 7 . IND INDEPENDENT rptListOfParticipatingPoliticalParties - Page 1 of 1 1 Election Commission of India - State Election, 1957 to the Legislative Assembly of Bihar OTHER ABBREVIATIONS AND DESCRIPTION ABBREVIATION DESCRIPTION FD Forfeited Deposits Gen General Constituency SC Reserved for Scheduled Castes ST Reserved for Scheduled Tribes M Men W Women T Total N National Party S State Party U Registered (Unrecognised) Party Z Independent rptOtherAbbreviations - Page 1 of 1 2 Election Commission of India - State Election, 1957 to the Legislative Assembly of Bihar HIGHLIGHTS 1. NO. OF CONSTITUENCIES TYPE OF CONSTITUENC GEN SC ST TOTAL NO. OF CONSTITUENCIE 196 39 29 264 2. NO. OF CONTESTANTS NO. -

Professional Ethics of Library Development and Services

NCPELDS - 2019 National Conference on Professional Ethics of Library Development and Services April 20, 2019 (Saturday) Venue: Conference Hall, LN Mishra College of Business Management, Bhagwanpur Chowk, Muzaffarpur, Bihar Genesis of the Conference The Libraries are repositories for humanity’s knowledge; they are our past, our present, and our future. They are much more than storehouses for books, and include many other forms of data. The information available in libraries must be accessible to all people, regardless of education, age, or economic status. Retrieval of particular types of information requires specialized knowledge and database searches that are beyond the capabilities of many users, and particularly of undergraduates starting their university careers. Librarians need to share that knowledge with users, instructing them on how to use electronic resources and the Internet so they can do research on their own, while pointing out the limits and problems associated with electronic research. Libraries are also considered to be part of the service sector. We are living in the world of change and uncertainty. Professionals who work for the libraries have to learn the techniques of Leadership methods. The main objective of the conference is to provide library and information science professionals to understand and importance of Users Service and the overall development of library and librarianship. This one day National conference is a highly effective program and a platform which brings together library professionals to exchange their innovative ideas and research. The program will also provide an opportunity for the participants to carry hands-on-practice and to attend many expert sessions. About the Library Professionals About the Dr. -

Complainant(S): Respondent(S): Nandini Kumari CPIO : D/O

Hearing Notice Central Information Commission Baba Gang Nath Marg Munirka, New Delhi - 110067 011-26105682 http://dsscic.nic.in/online-link-paper-compliance/add File No. CIC/IOCLD/A/2018/172832 DATE : 13-09-2020 NOTICE OF HEARING FOR APPEAL/COMPLAINT Appellant(s)/Complainant(s): Respondent(s): Nandini Kumari CPIO : D/o. LATE SHRI RAGHUNATH PANDEY, R/o. 1. THE CPIO VILL- MADAPUR CHAUBE, PO-KHARAUNA, INDIAN OIL CORPORATION DISTT.-MUZAFFAPUR, BIHAR – 843113 LIMITED, NODAL CPIO, RTI CELL, Bihar,Muzaffarpur,843113 MARKETING DIVISION, BIHAR STATE OFFICE, LOKNAYAK JAIPRAKASH BHAWAN, (5TH FLOOR), DAK BUNGLOW CHOWK, PATNA, BIHAR- 800001 Date of RTI Date of reply,if Date of 1st Appeal Date of order,if any,of CPIO made,if any any,of First AA 09-05-2018 30-05-2018 25-06-2018 23-07-2018 1. Take notice that the above appeal/complaint in respect of RTI application dated 09-05-2018 filed by the appellant/complainant has been listed for hearing before Hon'ble Information Commissioner Mr. Neeraj Kumar Gupta at Venue VC Address on 12-10-2020 at 11:10 AM. 2. The appellant/complainant may present his/her case(s) in person or through his/her duly authorized representative. 3. (a) CPIO/PIO should personally attend the hearing; if for a compelling reason(s) he/she is unable to be present, he/she has to give reasons for the same and shall authorise an officer not below the rank of CPIO.PIO, fully acquainted with the facts of the case and bring complete file/file(s) with him. -

![UGC-HUMAN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT CENTRE Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi-221005 List of Participants of the 68Th Orientation Course [ June 13 – July 10, 2014] Sl](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8350/ugc-human-resource-development-centre-banaras-hindu-university-varanasi-221005-list-of-participants-of-the-68th-orientation-course-june-13-july-10-2014-sl-8148350.webp)

UGC-HUMAN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT CENTRE Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi-221005 List of Participants of the 68Th Orientation Course [ June 13 – July 10, 2014] Sl

UGC-HUMAN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT CENTRE Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi-221005 List of participants of the 68th Orientation Course [ June 13 – July 10, 2014] Sl. Title & Name Designation Address Affiliated University Name No. 1. Dr. Akhilendra Kumar Singh Assistant Professor DAV PG College, Varanasi, U.P. Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi (Psychology) 2. Dr. Balchand Prajapati Assistant Professor SLS, Ambedkar University, Kashmere Gate, New Delhi Ambedkar University, Delhi (Mathematics) 3. Dr. Gaurav Rao Assistant Professor Department of Education, C.S.J. M. University, Kanpur, U.P. C.S.J. M. University, Kanpur, U.P. (Education) 4. Dr. Jay Singh Assistant Professor in Government DPG College, Chitalanka, Teknar, Dantewada Bastar University, Jagdalpur (Psychology) Chhattisgarh 5. Dr. Jitendra Kumar Singh Assistant Professor Dept. of Economics, Hindu P.G. College, Zamania, U.P. V.B.S. Poorvanchal University, Jaunpur (Economics) 6. Dr. Kamaluddin Sheikh Assistant Professor DAV P.G. College, Varanasi, U.P. Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi (Psychology) 7. Dr. Manohar Lal Assistant Professor Department of Journalism and Mass Communication, M.G. M.G. Kashi Vidyapith, Varanasi (Core Faculty) Kashi Vidyapith, Varanasi, U.P. 8. Dr. (Ms) Marathe Hemlata Assistant Professor ( Royal College of Education and Research for Women, Mira Mumbai University, Mumbai Yashwant Education) Road (E), Thane, Maharashtra 9. Dr. Naveen Kumar Singh Assistant Professor/ KVK, Pilkhi, Mau, U.P. N.D. University of Agrl. & Technology, Subject Matter Kumarganj, Faizabad Specialist (Plant Protection) 10. Dr. Ram Ratan Paswan Assistant Professor Department of Education, Magadh University, Bodhgaya, Magadh University, Bodhgaya, Gaya, Gaya, Bihar Bihar 11. Dr. Rupesh Kumar Singh Assistant Professor Dept. of Economics, Kooba P.G. -

Mandatory Disclosure.Pdf

Babasaheb Bhimrao Ambedkar Bihar University, Muzaffarpur Directorate of Distance Education Mandatory disclosure in reference to UGC-DEB F.No. 12-9/2016(DEB-III), dated 24.08.2016 INDEX Sl. Description Page(s) No. 1 Name of the courses an offer. 02 – 03 2 Approval of the statutory bodies of the university. 04 – 05 3 Approval of Regulatory bodies (Complete approval letter). 06 – 09 4 Details of academic calendar. 10 5 Student strength – enrolled, appeared and passed the 11 examinations under ODL programmes during the last three academic sessions. 6 List of Study centres with complete address and details of 12 Coordinator and support services, face to face contact programmes etc. 7 List of Examination Centres. 13 8 Availability of SLMs on website. 14 9 Elaboration of academic MOU for ODL programmes. NA 10 Name and other details of Course Coordinator at the HQ 15 for each course. 11 Complete Prospectus / brochure covering all aspects of 16 – 59 ODL programmes. 12 Territorial Jurisdiction of University / Institution. 60 13 Minimum qualification of incumbent Subject Coordinators 61 – 62 / Counsellors at the Study Cetnres (programme wise-for all programmes) 14 Details of Faculty, Administrative officials 63 1. Name of the courses an offer. Sr. No Name of Programme (Traditional Courses in Bachelor’s Degree) 01 B.A. HONOURS IN HISTORY 02 B.A. HONOURS IN HINDI 03 B.A. HONOURS IN ENGLISH 04 B.A. HONOURS IN POLITICAL SCIENCE 05 B.A. HONOURS IN ECONOMICS 06 B.A. HONOURS IN SOCIOLOGY 07 B.COM. HONS IN COMMERCE 08 B.SC. HONOURS IN MATHEMATICS 09 B.A. -

To Download Order

IN THEWWW.LIVELAW.IN HIGH COURT OF JUDICATURE AT PATNA Civil Writ Jurisdiction Case No.3636 of 2019 ====================================================== Kunal Kaushal ... ... Petitioner/s Versus The State of Bihar and Ors ... ... Respondent/s ====================================================== Appearance : For the Petitioner/s : Mr. Dinu Kumar, Advocate Mr. Arvind Kumar Sharma, Advocate Mr. Ritu Raj, Advocate Ms. Ritika Rani, Advocate For the State : Mr. Ashutosh Ranjan Pandey, Advocate Mr. Shashi Shekhar Tiwary, AAG-15 For Chancellor : Mr. Rajendra Kumar Giri, Advocate For L.N.M.U. : Mr. Nadim Seraj, Advocate Mr. Amish Kumar, Advocate For P.U. : Mr. Sandip Kumar, Advocate Mr. Rohit Raj, Advocate For T.M.B.U. : Mr. Ashhar Mustafa, Advocate For B.N.M.U. : Mr. P.N. Shahi, Sr. Advocate Mr. Ritesh Kumar, Advocate For M.U. & V.K.S.U. Mr. P.N. Shahi, Sr. Advocate Mr. Ritesh Kumar, Advocate For J.P.U. : Mr. Ritesh Kumar, Advocate For B.R.A.B.U. : Mr. Sandeep Kumar, Advocate Mr. Indrajesh Kumar, Advocate Mr. Rohit Raj, Advocate For U.G.C. : Mr. Deepak Kumar, Advocate ====================================================== CORAM: HONOURABLE THE CHIEF JUSTICE and HONOURABLE MR. JUSTICE S. KUMAR ORAL ORDER (Per: HONOURABLE THE CHIEF JUSTICE) 17 22-03-2021 The typographical error at page No. 11 of the order dated 18.02.2021 is corrected to the extent that name of “Mr. Raju Giri” be read as “Mr. Rajendra Kumar Giri.” Patna High Court CWJC No.3636 of 2019(17) dt.22-03-2021 2/4 WWW.LIVELAW.IN Bar Council of India, respondent no. 8 has filed its affidavit enclosing the status report of the existing, infrastructure and lack thereof, based on the inspection carried out of all the Universities/Law Colleges within the State of Bihar. -

Vaishali Type Fl

1 USINESS F B & R O UR TE A U L T I M T S A N N I A I G L E E A A M M H H E E S S N N I I A A T T V V VVAAIISSHHAALLII IINNSSTTIITTUUTTEE OOFF BBUUSSIINNEESSSS && RRUURRAALL MMAANNAAGGEEMMEENNTT Estd. 1983 (Approved By AICTE, New Delhi) (Affiliated to B.R.A. Bihar University, Muzaffarpur) Institutional Area, Narayanpur Anant Road Muzaffarpur - 842002 (Bihar) Tele fax. : (0621) 2273020, Mobile : 9835256380, 9334888155 Email :[email protected] website : www.vibrm.in A VENTURE OF VIKAS SEVA SANSTHAN 2 Message It is a matter of great pride for me that Vaishali Institute of Business and Rural Management has came a long way since its inception in 1983. The long journey has been very hectic as well as productive. We have carved out a place for ourselves, solely on the basis of hard work, excellent academics and devotion to our cause. The future beckons us to do more and to rise still higher, This will be possible if all of us work sincerely. Indeed you students, too, are central to our existence and plans, and therefore have a great role to play in the future. It is a privilege to welcome you all and I, on behalf of everybody associated with Vaishali Institute of Business and Rural Management, assure you of a great learning experience and a brilliant career. Sd. N.P.S. Nanda Director 3 Message It gives me great pleasure to inform the stake holders of Vaishali Institute of Business & Rural Management be it students, parents, guardians, professionals, faculty and others who have created a "Name" as a premier management Institute of North Bihar. -

Right to Privacy with Special Reference to Dignity of Women 2016

RIGHT TO PRIVACY WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO DIGNITY OF WOMEN A THESIS Submitted for the award of Ph.D. Degree In the Faculty of Law to the University of Kota, Kota (Rajasthan) Submitted by: Supervised by: Rajani Prabha Gupta Dr. Kailash Chandra Sharma Research Scholar Principal (Retd.) University of Kota, Government Law College, Kota (Raj.) Jhalawar (Raj.) 2016 Dr. K.C. Sharma Dean & Principal (Retd.) University of Kota, Kota (Raj.) Government Law College, Jhalawar (Raj.) CERTIFICATE FROM THE SUPERVISOR It is certified that the (i) Thesis “Right to Privacy with Special Reference to Dignity of Women” Submitted by Rajani Prabha Gupta, is an original copy of research work carried out by the candidate under my supervision. (ii) Her literary presentation is satisfactory and the thesis is in a form suitable for publication. (iii) Work evinces the capacity of the candidate for critical examination and independent judgment. The thesis incorporates new facts and a fresh approach towards their interpretation and systematic presentation. (iv) Rajani Prabha Gupta has put in at least 200 days of attendance every year. Date: 16.08.2016 Dr. K.C. Sharma Place : Kota Supervisor (i) PREFACE In this study the researcher has examined in detail the “Right to Privacy with Special Reference to Dignity of Women.” It is intended that such a study will help determine the parameters which any legislation for society must include. The acknowledgement of the debt to other is always a pleasant task. The help given by those mentioned in this acknowledgement has been of paramount value. Despite best efforts, non-acknowledgement to some worthy patrons cannot be completely ruled out but their contribution has been equally valuable. -

Human Resource Management

Human Resource Management I iBooks Author 2 Human Resource CHAPTER Management This document is authorized for internal use only at IBS campuses - Batch of 2012-2014 - Semester II. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieved system, used in a spreadsheet, or transmitted in any form or by means - electronic , mechanical, photocopying or otherwise - without prior permission in writing from IBS Hyderabad. iBooks Author 1 HAPTER C Introduction to Human Resource Management Human resources is one of the most valuable and given way to new approaches characterized by greater unique assets of an organization. According to Leon C. freedom and support to the employee. This Megginson, the term human resources refers to “the total transformation is almost complete and many successful knowledge, skills, creative abilities, talents and aptitudes companies today empower their employees to manage of an organization’s workforce, as well as the values, most aspects of their work. attitudes and beliefs of the individuals involved.1” Management as a process involves planning, organizing, staffing, leading and controlling activities that facilitate the achievement of an organization’s objectives. All these activities are accomplished through efficient utilization of physical and financial resources by the company’s human resources. Human resource management is one of the most complex and challenging fields of modern management. A human resource manager has to build up an effective workforce, handle the expectations of the employees and ensure that they perform at their best. He/she also has to take into account the firm’s responsibilities to the society that it operates in. -

Vaishali Prospectus.Cdr

VAISHALI INSTITUTE OF BUSINESS & RURAL MANAGEMENT Approved by AICTE & Affiliated to B.R.A. Bihar University (A Venture of Vikas Seva Sansthan) Founder Late Raghunath Pandey 08-03-1922 to 24-09-2001 (Former State Minister, Bihar) VAISHALI INSTITUTE OF BUSINESS & RURAL MANAGEMENT Approved by AICTE & Affiliated to B.R.A. Bihar University (A Venture of Vikas Seva Sansthan) 1 Message It is a matter of great pride for me that Vaishali Institute of Business and Rural Management has came a long way since its inception in 1983. The long journey has been very hectic as well as productive. We have carved out a place for ourselves, solely on the basis of hard work, excellent academics and devotion to our cause. The future beckons us to do more and to rise still higher. This will be possible if all of us work sincerely. Indeed you students, too, are central to our existence and plans, and therefore have a great role to play in the future. It is a privilege to welcome you all and I, on behalf of everybody associated with Vaishali Institute of Business and Rural Management, assure you of a great learning experience and a brilliant career. Sd. N.P.S. Nanda Director 2 Message It gives me great pleasure to inform the stake holders of Vaishali Institute of Business & Rural Management be it students, parents, guardians, professionals, faculty and others who have created a "Name" as a premier management Institute of North Bihar. Indeed It has been arduous yet satisfying journey. All along, our commitment to excellence, in everything we do, and our faith in our abilities, to deliver in the face of various odds, stood us in good stead.