Right to Privacy with Special Reference to Dignity of Women 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parliament of India R a J Y a S a B H a Committees

Com. Co-ord. Sec. PARLIAMENT OF INDIA R A J Y A S A B H A COMMITTEES OF RAJYA SABHA AND OTHER PARLIAMENTARY COMMITTEES AND BODIES ON WHICH RAJYA SABHA IS REPRESENTED (Corrected upto 4th September, 2020) RAJYA SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI (4th September, 2020) Website: http://www.rajyasabha.nic.in E-mail: [email protected] OFFICERS OF RAJYA SABHA CHAIRMAN Shri M. Venkaiah Naidu SECRETARY-GENERAL Shri Desh Deepak Verma PREFACE The publication aims at providing information on Members of Rajya Sabha serving on various Committees of Rajya Sabha, Department-related Parliamentary Standing Committees, Joint Committees and other Bodies as on 30th June, 2020. The names of Chairmen of the various Standing Committees and Department-related Parliamentary Standing Committees along with their local residential addresses and telephone numbers have also been shown at the beginning of the publication. The names of Members of the Lok Sabha serving on the Joint Committees on which Rajya Sabha is represented have also been included under the respective Committees for information. Change of nominations/elections of Members of Rajya Sabha in various Parliamentary Committees/Statutory Bodies is an ongoing process. As such, some information contained in the publication may undergo change by the time this is brought out. When new nominations/elections of Members to Committees/Statutory Bodies are made or changes in these take place, the same get updated in the Rajya Sabha website. The main purpose of this publication, however, is to serve as a primary source of information on Members representing various Committees and other Bodies on which Rajya Sabha is represented upto a particular period. -

Procurement of Stores and Inventory Control

37 PROCUREMENT OF STORES AND INVENTORY CONTROL [Action Taken by the Government on the Observations/ Recommendations of the Committee contained in their Eighteenth Report (15th Lok Sabha)] DEPARTMENT OF SPACE PUBLIC ACCOUNTS COMMITTEE 2011-2012 THIRTY SEVENTH REPORT FIFTEENTH LOK SABHA LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI THIRTY SEVENTH REPORT PUBLIC ACCOUNTS COMMITTEE (2011-2012) (FIFTEENTH LOK SABHA) PROCUREMENT OF STORES AND INVENTORY CONTROL [Action Taken by the Government on the Observations/Recommendations of the Committee contained in their Eighteenth Report (15th Lok Sabha)] DEPARTMENT OF SPACE Presented to Lok Sabha on 11.8.2011 Laid in Rajya Sabha on 11.8.2011 LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI August, 2011/Sravana, 1933 (Saka) PAC No. 1944 Price: ` 31.00 © 2011 BY LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT Published under Rule 382 of the Rules of Procedure and Conduct of Business in Lok Sabha (Fourteenth Edition) and Printed by the General Manager, Government of India Press, Minto Road, New Delhi-110 002. CONTENTS CONTENTS PAGE COMPOSITION OF THE PUBLIC A CCOUNTS COMMITTEE (2011-12) ..................... (iii) INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................... (v) CHAPTER I. Report .............................................................................. 1 CHAPTER II. Observations/Recommendations which have been accepted by Government ................................................. 5 CHAPTER III. Observations/Recommendations which the Committee do not desire to pursue in view of the replies received from Government ...................................................................... 20 CHAPTER IV. Observations/Recommendations in respect of which replies of Government have not been accepted by the Committee and which require reiteration .......................... 21 CHAPTER V. Observations/Recommendations in respect of which Government have furnished interim replies...................... 22 APPENDICES I. Minutes of the Second Sitting of Public Accounts Committee (2011-12) held on 28th June, 2011 .................. -

In the Media

Copyrights © 2014 Business Standard Ltd. All rights reserved. Business Standard - Mumbai; Size : 221 sq.cm.; Page : 12 Friday, 25 March, 2016 Copyright © 2014 Bennett Coleman & Co. Ltd. ? All rights reserved Economic Times - Mumbai; Size : 134 sq.cm.; Page : 5 Saturday, 26 March, 2016 Copyright © 2014 Bennett Coleman & Co. Ltd. ? All rights reserved Economic Times - Hyderabad; Size : 185 sq.cm.; Page : 11 Saturday, 26 March, 2016 Copyright © 2014 HT Media All Rights Reserved Mint - Delhi; Size: 255 Sq.cm. Page: 8 Saturday, 26 March, 2016 Copyright © 2014 Bennett Coleman & Co. Ltd.? All rights reserved Times Of India - Kolkata; Size : 151 sq.cm.; Page : 1 Saturday, 26 March, 2016 Copyright © 2014 HT Media All Rights Reserved Hindustan Times - Kolkata; Size : 154 sq.cm.; Page : 10 Saturday, 26 March, 2016 Copyright © 2014 The Telegraph. All rights reserved. Telegraph - Kolkata; Size : 122 sq.cm.; Page : 6 Saturday, 26 March, 2016 Copyright 2014, The Printers (Mysore) Private Ltd. Deccan Herald - Delhi; Size : 186 sq.cm.; Page : 14 Saturday, 26 March, 2016 Copyright © 2014 The Pioneer. All Rights Reserved. Pioneer - Delhi; Size : 166 sq.cm.; Page : 7 Saturday, 26 March, 2016 Copyright © 2014 The Statesman Limited. All Rights Reserved. Statesman - Delhi; Size : 353 sq.cm.; Page : 2 Saturday, 26 March, 2016 Copyright © 2014 The Pioneer. All Rights Reserved. Pioneer - Delhi; Size : 117 sq.cm.; Page : 10 Saturday, 26 March, 2016 © Millennium Post. All Rights Reserved Millennium Post - Delhi; Size : 426 sq.cm.; Page : 12 Saturday, 26 March, 2016 Copyright © 2012 Living Media India Limited. For reprint rights Mail Today - Delhi; Size : 557 sq.cm.; Page : 30 Saturday, 26 March, 2016 The Hans India - Hyd; Size : 526 sq.cm.; Page : 7 Saturday, 26 March, 2016 Copyright © 2006- 2014 Diligent Media Corporation Ltd. -

List of Successful Candidates

11 - LIST OF SUCCESSFUL CANDIDATES CONSTITUENCY WINNER PARTY Andhra Pradesh 1 Nagarkurnool Dr. Manda Jagannath INC 2 Nalgonda Gutha Sukender Reddy INC 3 Bhongir Komatireddy Raj Gopal Reddy INC 4 Warangal Rajaiah Siricilla INC 5 Mahabubabad P. Balram INC 6 Khammam Nama Nageswara Rao TDP 7 Aruku Kishore Chandra Suryanarayana INC Deo Vyricherla 8 Srikakulam Killi Krupa Rani INC 9 Vizianagaram Jhansi Lakshmi Botcha INC 10 Visakhapatnam Daggubati Purandeswari INC 11 Anakapalli Sabbam Hari INC 12 Kakinada M.M.Pallamraju INC 13 Amalapuram G.V.Harsha Kumar INC 14 Rajahmundry Aruna Kumar Vundavalli INC 15 Narsapuram Bapiraju Kanumuru INC 16 Eluru Kavuri Sambasiva Rao INC 17 Machilipatnam Konakalla Narayana Rao TDP 18 Vijayawada Lagadapati Raja Gopal INC 19 Guntur Rayapati Sambasiva Rao INC 20 Narasaraopet Modugula Venugopala Reddy TDP 21 Bapatla Panabaka Lakshmi INC 22 Ongole Magunta Srinivasulu Reddy INC 23 Nandyal S.P.Y.Reddy INC 24 Kurnool Kotla Jaya Surya Prakash Reddy INC 25 Anantapur Anantha Venkata Rami Reddy INC 26 Hindupur Kristappa Nimmala TDP 27 Kadapa Y.S. Jagan Mohan Reddy INC 28 Nellore Mekapati Rajamohan Reddy INC 29 Tirupati Chinta Mohan INC 30 Rajampet Annayyagari Sai Prathap INC 31 Chittoor Naramalli Sivaprasad TDP 32 Adilabad Rathod Ramesh TDP 33 Peddapalle Dr.G.Vivekanand INC 34 Karimnagar Ponnam Prabhakar INC 35 Nizamabad Madhu Yaskhi Goud INC 36 Zahirabad Suresh Kumar Shetkar INC 37 Medak Vijaya Shanthi .M TRS 38 Malkajgiri Sarvey Sathyanarayana INC 39 Secundrabad Anjan Kumar Yadav M INC 40 Hyderabad Asaduddin Owaisi AIMIM 41 Chelvella Jaipal Reddy Sudini INC 1 GENERAL ELECTIONS,INDIA 2009 LIST OF SUCCESSFUL CANDIDATE CONSTITUENCY WINNER PARTY Andhra Pradesh 42 Mahbubnagar K. -

USAIC Summit Sets Stage

www.expresspharmaonline.com FORTNIGHTLY INSIGHT FOR PHARMA PROFESSIONALS 16-30 April 2009 Sections Home - Market - Article Printer Friendly Version Market Pre Event Brief Management Research USAIC Summit sets stage for 'bold, innovative' Pharma Life partnerships Packaging Special This year's US-India BioPharma & Healthcare Summit, scheduled Express Biotech for May 14 in Massachusetts, USA, promises to continue the Services efforts of the USA-India Chamber of Commerce (USAIC), a bilateral Chamber of Commerce aimed at promoting and Editorial Advisory Board facilitating trade and investment between the US and India. As Open Forum Karun Rishi, President of the USA-India Chamber of Commerce, Subscribe/Renew commented, "The positive side of current economic downturn is Archives the likely growth in discovery research business between India Media Kit and the US. Many US companies sitting on the fence will be Contact Us compelled to seriously consider integrating India in their global R&D strategy. This is the time for Indian companies to ramp up Network Sites their capacity and quality standards." Express Computer According to Dr. Martin Mackay, Co-Chair of the US-India Express Channel Business BioPharma & Healthcare Summit and President Global R&D, Pharmaceutical Express Hospitality Pfizer, "Pfizer has a network of research partners in biotech Companies Express TravelWorld companies, academic institutions, hospitals and contract research Access Company Express Healthcare organisations (CROs). This global network includes scientific Profiles, Find Group Sites collaborations with Indian researchers and dozens of planned and Sales Leads & ongoing clinical studies in India. As part of Pfizer strategies to Build Lists. Free ExpressIndia grow the business in emerging markets and pursue the best Trial! Indian Express science, our R&D organisation is leveraging the capabilities of www.selectory.com Financial Express this network to assist with drug discovery and development. -

List of Winning Candidated Final for 16Th

Leading/Winning State PC No PC Name Candidate Leading/Winning Party Andhra Pradesh 1 Adilabad Rathod Ramesh Telugu Desam Andhra Pradesh 2 Peddapalle Dr.G.Vivekanand Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 3 Karimnagar Ponnam Prabhakar Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 4 Nizamabad Madhu Yaskhi Goud Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 5 Zahirabad Suresh Kumar Shetkar Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 6 Medak Vijaya Shanthi .M Telangana Rashtra Samithi Andhra Pradesh 7 Malkajgiri Sarvey Sathyanarayana Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 8 Secundrabad Anjan Kumar Yadav M Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 9 Hyderabad Asaduddin Owaisi All India Majlis-E-Ittehadul Muslimeen Andhra Pradesh 10 Chelvella Jaipal Reddy Sudini Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 11 Mahbubnagar K. Chandrasekhar Rao Telangana Rashtra Samithi Andhra Pradesh 12 Nagarkurnool Dr. Manda Jagannath Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 13 Nalgonda Gutha Sukender Reddy Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 14 Bhongir Komatireddy Raj Gopal Reddy Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 15 Warangal Rajaiah Siricilla Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 16 Mahabubabad P. Balram Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 17 Khammam Nama Nageswara Rao Telugu Desam Kishore Chandra Suryanarayana Andhra Pradesh 18 Aruku Deo Vyricherla Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 19 Srikakulam Killi Krupa Rani Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 20 Vizianagaram Jhansi Lakshmi Botcha Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 21 Visakhapatnam Daggubati Purandeswari -

17.03.2015 by an Order Passed by the Hon'ble Supreme Court in Civil

17.03.2015 SUPPLEMENTARY LIST SUPPLEMENTARY LIST FOR TODAY IN CONTINUATION OF THE ADVANCE LIST ALREADY CIRCULATED. THE WEBSITE OF DELHI HIGH COURT IS www.delhihighcourt.nic.in INDEX PRONOUNCEMENT OF JUDGMENTS ------------> J- 1 TO 03 REGULAR MATTERS -----------------------> R- 1 TO 63 FINAL MATTERS (ORIGINAL SIDE) ---------> F- 1 TO 11 ADVANCE LIST --------------------------> 1 TO 84 APPELLATE SIDE (SUPPLEMENTARY LIST)----> 85 TO 106 (FIRST PART) APPELLATE SIDE (SUPPLEMENTARY LIST)----> 107 TO 116 (SECOND PART) COMPANY -------------------------------> 117 TO 119 ORIGINAL SIDE (SUPPLEMENTARY I)--------> 120 TO 130 SECOND SUPPLEMENTARY ------------------> 131 TO NOTES 1. Urgent mentioning may be made before Hon'ble DB-II at 10.30 A.M. By an order passed by the Hon'ble Supreme Court in Civil Appeal No. 7400/2014, it has been held that against an order passed by the Armed Forces Tribunal, a Writ Petition under Article 226 of the Constitution of India cannot be entertained by the High Court and that the remedy for the aggrieved person is in terms of Section 30 and 31 of the Armed Forces Tribunal Act, 2007. Accordingly, the Writ Petitions pending in this High Court against the orders passed by the Armed Forces Tribunal will be listed for directions before Hon'ble DB-III on 20.03.2015. DELETIONS 1. W.P.(C) 628/2015 listed before Hon'ble DB-IV at item No.17 is deleted as the same is fixed for 07.04.2015. 2. W.P.(C) 5883/2012 listed before Hon'ble Mr. Justice Valmiki J. Mehta at item No.6 is deleted as the same is listed before Hon'ble Mr. -

The Legislative Assembly of Bihar

STATISTICAL REPORT ON GENERAL ELECTION, 1990 TO THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF BIHAR ELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA NEW DELHI Election Commission of India – General Elections, 1990 to the Legislative Assembly of Bihar STATISTICAL REPORT CONTENTS SUBJECT Page No. 1. List of Participating Political Parties and Abbreviations 1 - 2 2. Other Abbreviations in the Report 3 3. Highlights 4 4. List of Successful Candidates 5 - 12 5. Performance of Political Parties 13 -14 6. Electors Data Summary – Summary on Electors, voters 15 Votes Polled and Polling Stations 7. Woman Candidates 16 - 23 8. Constituency Data Summary 24 - 347 9. Detailed Result 348 - 496 Election Commission of India-State Elections, 1990 to the Legislative Assembly of BIHAR LIST OF PARTICIPATING POLITICAL PARTIES PARTYTYPE ABBREVIATION PARTY NATIONAL PARTIES 1 . BJP BHARTIYA JANATA PARTY 2 . CPI COMMUNIST PARTY OF INDIA 3 . CPM COMMUNIST PARTY OF INDIA (MARXIST) 4 . ICS(SCS) INDIAN CONGRESS (SOCIALIST-SARAT CHANDRA SINHA) 5 . INC INDIAN NATIONAL CONGRESS 6 . JD JANATA DAL 7 . JNP(JP) JANATA PARTY (JP) 8 . LKD(B) LOK DAL (B) STATE PARTIES 9 . BSP BAHUJAN SAMAJ PARTY 10 . FBL ALL INDIA FORWARD BLOC 11 . IML INDIAN UNION MUSLIM LEAGUE 12 . JMM JHARKHAND MUKTI MORCHA 13 . MUL MUSLIM LEAGUE REGISTERED(Unrecognised ) PARTIES 14 . ABSP AKHIL BAHARTIYA SOCIALIST PARTY 15 . AMB AMRA BANGALEE 16 . AVM ANTHARRASTRIYA ABHIMANYU VICHAR MANCH 17 . AZP AZAD PARTY 18 . BBP BHARATIYA BACKWARD PARTY 19 . BDC BHARAT DESHAM CONGRESS 20 . BJS AKHIL BHARATIYA JANA SANGH 21 . BKUS BHARATIYA KRISHI UDYOG SANGH 22 . CPI(ML) COMMUNIST PARTY OF INDIA (MARXIST-LENINIST) 23 . DBM AKHIL BHARATIYA DESH BHAKT MORCHA 24 . -

Nse: Indiamart

28 IndiaMART InterMESH Ltd. 6th floor, Tower 2, Assotech Business Cresterra, Plot No.22, Sec 135, Noida-201305, U.P Call Us: +91 - 9696969696 = = 1D) E: [email protected] in lama Website: www.indiamart.com The Manager - Listing Date: August 06, 2020 BSE Limited (BSE: 542726) The Manager - Listing National Stock Exchange of India Limited (NSE: INDIAMART) Dear Sir/Ma’am, Subject: Notice of 21st Annual General Meeting (AGM) and Annual Report 2019-20 In compliance with Regulation 34, 44 and other applicable provisions of the SEBI (Listing Obligations and Disclosure Requirements) Regulations, 2015, read with the General Circular No. 14/2020 dated April 08, 2020, the General Circular No. 17/2020 dated April 13, 2020, General Circular No. 20/2020 dated May 05, 2020, issued by the Ministry of Corporate Affairs and the Circular No. SEBI/HO/CFD/CMD1/CIR/P/2020/79 dated May 12, 2020, issued by the Securities and Exchange Board of India, please find enclosed the copy of notice dated July 21, 2020 along with Annual Report for the Financial Year 2019-20 for convening the 21st Annual General Meeting (AGM) of the Company to be held on Monday, August 31, 2020 at 4:00 p.m. through Video Conferencing/ Other Audio Visual Means. Notice of 21st AGM and Annual Report for the Financial Year 2019-20 is being sent today to all the members of the Company whose email addresses are registered with the Company or Depository Participant(s). Notice of 21st AGM and Annual Report for the Financial Year 2019-20 are also made available on the Company’s website at http://investor.indiamart.com. -

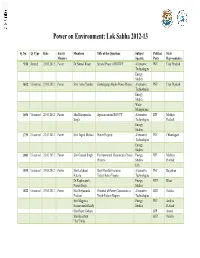

Power on Environment: Lok Sabha 2012-13

Power on Environment: Lok Sabha 2012-13 Q. No. Q. Type Date Ans by Members Title of the Questions Subject Political State Ministry Specific Party Representative *150 Starred 23.03.2012 Power Dr.Nirmal Khatri Second Phase of RGGVY Alternative INC Uttar Pradesh Technologies Energy Studies 1612 Unstarred 23.03.2012 Power Smt. Annu Tandon Kishanganga Hydro Power Project Alternative INC Uttar Pradesh Technologies Energy Studies Water Management 1656 Unstarred 23.03.2012 Power Shri Bhoopendra Agencies under RGGVY Alternative BJP Madhya Singh Technologies Pradesh Energy Studies 1739 Unstarred 23.03.2012 Power Smt. Ingrid Mcleod Power Projects Alternative INC Chhattisgarh Technologies Energy Studies 1803 Unstarred 23.03.2012 Power Shri Ganesh Singh Environmental Clearance to Power Energy BJP Madhya Projects Studies Pradesh EIA 1819 Unstarred 23.03.2012 Power Shri Lalchand Rajiv Gandhi Grameen Alternative INC Rajasthan Kataria Vidyutikaran Yojana Technologies Dr.Raghuvansh Energy RJD Bihar Prasad Singh Studies 1832 Unstarred 23.03.2012 Power Shri Nityananda Potential of Power Generation in Alternative BJD Odisha Pradhan North-Eastern Region Technologies Shri Magunta Energy INC Andhra Sreenivasulu Reddy Studies Pradesh Shri Rajen Gohain BJP Assam Shri Baijayant BJD Odisha "Jay"Panda Shri Kirti (Jha)Azad BJP Bihar *241 Starred 30.3.2012 Power Shri Power Projects Alternative CPI(M) Kerala Parayamparanbil Technologies Kuttappan Biju Rajkumari Ratna Energy INC Uttar Pradesh Singh Studies *249 Starred 30.3.2012 Power Shri Maheshwar Power Projects of NTPC Energy JD(U) Bihar Hazari Studies Shri Lalchand INC Rajasthan Kataria Starred 30.03.2012 Power Shri Ijyaraj Singh Access to Electricity Alternative INC Rajasthan *250 Technologies Shri Nityananda Energy BJD Odisha Pradhan Studies *257 Starred 30.03.2012 Power Smt. -

High Court of Delhi Advance Cause List

HIGH COURT OF DELHI ADVANCE CAUSE LIST LIST OF BUSINESS FOR TUESDAY, THE 09th SEPTEMPER,2014 INDEX PAGES 1. APPELLATE JURISDICTION 01 TO 35 2. COMPANY JURISDICTION 36 TO 38 3. ORIGINAL JURISDICTION 39 TO 51 4. REGISTRAR GENERAL/ 52 TO 68 REGISTRAR(ORGL.)/ REGISTRAR (ADMN.)/ JOINT REGISTRARS(ORGL). 09.09.2014 1 (APPELLATE JURISDICTION) 09.09.2014 [Note : Unless otherwise specified, before all appellate side courts, fresh matters shown in the supplementary lists will be taken up first.] COURT NO. 1 (DIVISION BENCH-1) HON'BLE THE CHIEF JUSTICE HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE RAJIV SAHAI ENDLAW AFTER NOTICE MISC. MATTERS 1. LPA 891/2011 UNION OF INDIA AND ANR SACHIN DATTA,G DURGA CM APPL. 19817/2011 Vs. BEST LABORATORIES PVT LTD BOSS,ANSHUL TYAGI,ANANT GARG 2. LPA 859/2013 SHIMAL INVESTMENT AND TRADING K DATTA AND ASSOCIATES,SACHIN CM APPL. 18085/2013 CO (PRESENTLY KNOWN AS RHC DATTA,ZUBEDA BEGUM HOLDING PRIVATE LIMITED) Vs. UNION OF INDIA AND ORS 3. LPA 894/2013 UNION OF INDIA AND ANR SACHIN DATTA Vs. SHIMAL INVESTMENT AND TRADING CO AFTER NOTICE MISC. MATTERS FOR FINAL HEARING (CONNECTED MATTERS)/PH 4. LPA 125/2014 TATA POWER DELHI DISTRIBUTION J SAGAR ASSOCIATES,DR BANARSI CM APPL. 2434/2014 LIMITED DAS,PRASHANT BHUSHAN CM APPL. 3297/2014 Vs. COMPTROLLER AND AUDITOR CM APPL. 4031/2014 GENERAL OF INDIA AND ORS WITH W.P.(C) 559/2014 5. W.P.(C) 559/2014 TATA POWER DELHI DISTRIBUTION J SAGAR AND CM APPL. 1125/2014 LTD ASSOCIATES,GAURANG CM APPL. 6419/2014 Vs. THE COMPTROLLER AND KANTH,PRASHANT BHUSHAN AUDITOR GENERAL OF INDIA AND ORS. -

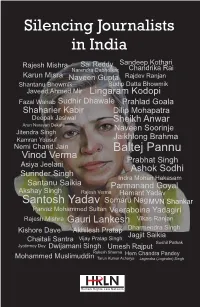

Silencing Journalists in India

In India, journalists have come under repeated attacks in the recent times. They have been killed, arrested, and Silencing Journalists wrongly implicated in many cases. There have been increasing number of criminal cases against journalists. in India Many media houses have seen their offices ransacked. It is sufficient to say that there have not been darker times for Sai Reddy Sandeep Kothari Rajesh Mishra Chandrika Rai journalists in India as it has been in the recent past and now. Narendra Dabholkar Karun Misra Rajdev Ranjan It is in this context that this compilation is brought out. This Naveen Gupta Shantanu Bhowmik Sudip Datta Bhowmik compilation brings out the stories of the journalists who Javeed Ahmed Mir Lingaram Kodopi have been arrested and killed for performing their duty. Attack on Journalists in India Fazal Wahab Sudhir Dhawale Prahlad Goala “Journalism can never be silent: That is its greatest virtue Shaharier Kabir Dilip Mohapatra and its greatest fault. It must speak, and speak immedi- Deepak Jasiwal Sheikh Anwar ately, while the echoes of wonder, the claims of triumph Arun Narayan Dekate Naveen Soorinje and the signs of horror are still in the air.” Jitendra Singh Kamran Yousuf Jaikhlong Brahma — Henry Anatole Grunwald, Nemi Chand Jain Baltej Pannu former Managing Editor, Time Magazine Vinod Verma Prabhat Singh “Journalism will kill you, but it will keep you alive while Asiya Jeelani Ashok Sodhi you’re at it.” Surinder Singh Indra Mohan Hakasam — Horace Greeley, Santanu Saikia Parmanand Goyal founder and editor of New