The New Public Domain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Video Game Archive: Nintendo 64

Video Game Archive: Nintendo 64 An Interactive Qualifying Project submitted to the Faculty of WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science by James R. McAleese Janelle Knight Edward Matava Matthew Hurlbut-Coke Date: 22nd March 2021 Report Submitted to: Professor Dean O’Donnell Worcester Polytechnic Institute This report represents work of one or more WPI undergraduate students submitted to the faculty as evidence of a degree requirement. WPI routinely publishes these reports on its web site without editorial or peer review. Abstract This project was an attempt to expand and document the Gordon Library’s Video Game Archive more specifically, the Nintendo 64 (N64) collection. We made the N64 and related accessories and games more accessible to the WPI community and created an exhibition on The History of 3D Games and Twitch Plays Paper Mario, featuring the N64. 2 Table of Contents Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………………………… 2 Table of Contents…………………………………………………………………………………………. 3 Table of Figures……………………………………………………………………………………………5 Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………………………….. 7 Executive Summary………………………………………………………………………………………. 8 1-Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………………….. 9 2-Background………………………………………………………………………………………… . 11 2.1 - A Brief of History of Nintendo Co., Ltd. Prior to the Release of the N64 in 1996:……………. 11 2.2 - The Console and its Competitors:………………………………………………………………. 16 Development of the Console……………………………………………………………………...16 -

Stupidman 64

issue 1. – January 2015 stupidman 64. By popo. Oh wait. The game is called Superman 64. I’m sorry. Sorry I ever played this piece of garbage. It’s the kind that makes you wonder if game testers were used. After about 15 minutes it occurs to me that in order to fly, you press B+Z and then fly around with the control stick. But that It would at least not give me a doesn’t really help much if you time limit. No wonder Superman don’t know where to fly to. looks angry in the packaging. Luthor’s message isn’t much help. He’s trapped inside this hideous game. Not only that, I think Titus ripped off the Virtual Boy font. And so Superman never saw his friends again because Luthor’s plot worked too well. Too bad he doesn’t kill Superman. Too bad Gee, I can’t solve your maze. It Titus released this POS game. I’d ends abruptly in front of a rather play Penny Racers. building that I can’t go into. And Review: not only that, you have 90 seconds + cartridge makes a nice coaster to solve it. Then Luthor “wins” - game doesn’t work even if you and you press A to start level plug it in and start playing it. ONE over again. I know what Ratings (out of 10) Luthor wins. A wipe from my Graphics – 4 | Play control – 1 butt. If I felt like flying around pointlessly, I’d get Pilotwings 64. total=1 what’s this? I know what you’re thinking. -

Copyrighted Material

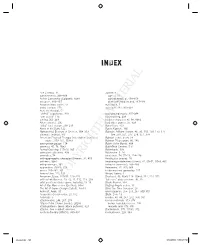

Index Ace Combat, 11 audience achievements, 368–369 age of, 29 Action Cartooning (Caldwell), 84n1 control needs of, 158–159 actuators, 166–167 pitch presentation and, 417–421 Advance Wars series, 11 Auto Race, 7 aerial combat, 270 autosave, 192, 363–364 Aero the Acrobat, 52 “ah-ha!” experience, 349 background music, 397–398 “aim assist,” 173 backtracking, 228 aiming, 263–264 badass character, 86–88, 86n2 Aliens (movie), 206 bad video games, 25, 429 “alley” level design, 218–219 Band Hero, 403 Alone in the Dark, 122 Banjo-Kazooie, 190 Alphabetical Bestiary of Choices, 304–313 Batman: Arkham Asylum, 46, 50, 110, 150, 173, 177, alternate endings, 376 184, 250, 251, 277, 278, 351, 374 American Physical Therapy Association exercises/ Batman comic book, 54 advice, 159–161, 159n3 Batman TV program, 86, 146 ammunition gauge, 174 Battle of the Bands, 404 amnesia, 47, 76, 76n9 BattleTech Centers, 5–6 Animal Crossing, 117n10, 385 Battletoads, 338 animated cutscenes, 408 Battlezone, 5, 14 animatics, 74 beat chart, 74, 77–79, 214–216 anthropomorphic characters/themes, 92, 459 Beetlejuice (movie), 18 anti-hero, 86n2 beginning/middle/end (stories), 41, 50–51, 50n9, 435 anti-power-ups, 361 behavior (enemies), 284–289 appendixes (GDD), 458 Bejeweled, 41, 350, 368 armor, 259–261, 361 bi-dimensional gameplay, 127 Army of Two, 112, 113 Bilson, Danny, 3 Arnenson, Dave, 217n13, 223–229 Bioshock, 46, 46n9, 118, 208n9, 212, 214, 372 artifi cial intelligence, 13,COPYRIGHTED 42, 71, 112, 113, 293 “bite-size” MATERIAL play sessions, 46, 79 artist positions (video game industry), 13–14 Blade Runner, 397 Art of Star Wars series (Del Rey), 84n1 Blazing Angels series, 11 The Art of Game Design (Schell), 15n14 Blinx: the Time Sweeper, 26 Ashcraft, Andy, 50 blocks/parries, 258–259, 287, 300–301 Assassin’s Creed series, 21, 172 Bluth, Don, 13 Asteroids, 5 bombs, 47–48, 247, 272, 358, 381 attack matrix, 248, 267, 279 bonus materials, 373–376 Attack of the Clones (movie), 202n6 bonus materials screen, 195 attack patterns (boss attack patterns), 323 rewards and, 373–376 attacks. -

How Comics Communicate on the Screen Telecinematic Discourse in Comic-To-Film Adaptations

In: Christian Hoffmann & Monika Kirner-Ludwig (eds.). 2020. Telecinematic Stylistics. London: Bloomsbury. 263-284. 11 How comics communicate on the screen Telecinematic discourse in comic-to-film adaptations Christina Sanchez-Stockhammer 1 Introduction Recent years have seen a large number of commercially successful screen adaptations of printed comic books, such as Kenneth Branagh’s Thor (2011) or the award-winning series of Batman films (e.g. Christopher Nolan’s2008 The Dark Knight).1 Most of these screen adaptations of comics, like most studies of ‘graphic cinema’ (e.g. Booker 2007; Gordon, Jancovich and McAllister 2007; Rauscher 2010), focus on relatively dark superheroes.2 Against this background, one box-office success stands out due to its friendly and positive hero for all audiences: Steven Spielberg’s The Adventures of Tintin (2011), which is based on the comic book series Tintin by the Belgian artist Hergé (a pseudonym for Georges Rémi; cf. Peeters 1990: 9). In Hergé’s comics, the young journalist Tintin experiences exciting adventures all over the world in the company of his dog Snowy. This chapter pays tribute to Hergé’s popular comic book universe by investigating the relation between Spielberg’s film adaptation and Hergé’s comics from a linguistic perspective. It sets out to fill an important research gap by exploring how language use in the scriptovisual3 medium of the comic (which combines still images and printed text) is rendered in the audiovisual medium of film (which combines moving images and spoken language). After discussing general linguistic similarities between comics and films and the use of language in each of the two media, this chapter compares the representation of voice, accent, thoughts, talking animals, sounds and written language in Spielberg’s screen adaptation of Tintin to the original printed comic books. -

2. What Is a Good Game?

Game and Learn: An Introduction to Educational Gaming 2. What Is A Good Game? Ruben R. Puentedura, Ph.D A Tale Of Two Games One of The Best Videogames of All Time: Pitfall! One of The Worst Videogames of All Time: ET What Makes a Game Fun? Games and Boredom When Players Say… …They Mean The game is too easy Game patterns are too simple Players are uninterested in the The game is too involved information required to detect patterns The game is too hard Patterns are perceived as noise The game becomes too repetitive New patterns are added too slowly The game becomes too hard New patterns are added too fast The game runs out of options All game patterns are exhausted Games and Boredom When Players Say… …They Mean The game is too easy Game patterns are too simple Players are uninterested in the The game is too involved information required to detect patterns The game is too hard Patterns are perceived as noise The game becomes too repetitive New patterns are added too slowly The game becomes too hard New patterns are added too fast The game runs out of options All game patterns are exhausted Games and Boredom When Players Say… …They Mean The game is too easy Game patterns are too simple Players are uninterested in the The game is too involved information required to detect patterns The game is too hard Patterns are perceived as noise The game becomes too repetitive New patterns are added too slowly The game becomes too hard New patterns are added too fast The game runs out of options All game patterns are exhausted Successful Games Include -

The Crimson Chronicle 1521 N

Hollywood High • Home of the Sheiks The Crimson Chronicle 1521 N. HIGHLAND AVE, LOS ANGELES, CA 90028 VOLUME VII, ISSUE I OCTOBER 2009 Test Scores Skyrocket 89 Points KIARA HURTADO years to improve by this much. ment, meaning this school did NEWS EDITOR The average score that the School 2009 Score not meet the required API score school receives on the CST, de- of 800 points, the highest being Hollywood High School met termines the ranking of the Fairfax 733 1000 points. In order to get out the school’s target for the Aca- school. This report helps con- of Program Improvement, the demic Performance Index (API) clude which schools need to Hollywood 702 school must meet the API target Report. The API score is the improve and which schools are Marshall 665 for two consecutive years. Since overall student scores of the doing well academically. HHS met the target last school California Standards Test (CST), After comparing Hollywood’s Bernstein 541 year, HHS must meet that tar- which was taken in May. API score with other high school get once more this school year The API score increased by 89 scores, Hollywood ranked sec- to get out of Program Improve- points for the 2008-09 school ond most improved compre- nities and traditional calendar, lieves it was the “demographic ment. year. Hollywood went from hensive high school in all of said Principal Jaime Morales. changes,” like the addition of Morales says he wants to scoring 613 points in 2007-08 California. HHS also ranked the HHS went through a lot of advisories that helped HHS im- thank “all teachers and stu- to 702 points in 2008-09. -

Crisis of Infinite Intertexts! Continuity As Adaptation in the Superman Multimedia Franchise

Crisis of Infinite Intertexts! Continuity as Adaptation in the Superman Multimedia Franchise Jack Peterson Teiwes ORCID identifier 0000-0001-8956-1602 Doctor of Philosophy November 2015 School of Culture and Communication The University of Melbourne Submitted in total fulfillment of the requirements of the PhD degree Produced on archival quality paper Abstract Since first appearing as a comic book character over three quarters of a century ago, Superman was not only the first superhero, spawning an entire genre of imitators, but also quickly became one of the most widely disseminated multi-media entertainment franchises. This achieved a degree of intergenerational cultural dissemination that far surpasses his comic book fandom. Yet despite an unprecedented degree of adaptation into other media from radio, newspaper strips, film serials, animation, feature films, video games and television, Superman’s ongoing comic books have remained in unbroken publication, developing a long and complex history of narrative renewal and reinvention. This thesis investigates the multifaceted intertextuality between the comic book portrayals of Superman and its many adaptations over the years, including how such retellings in other media have a generally stronger cultural impact, which exerts in turn an adaptive influence upon these continuing comics’ internalised narrative continuity. I shall argue that Superman comics, as a case study for the wider phenomenon in the superhero genre, demonstrate via their frequent revisions and relaunches of continuity, a process of deeply palimpsestuous self-adaptation. The Introduction positions my research methodology in relation to intertextual theory, with an emphasis on providing terminological clarity, while Chapter 1 expands into a literature review on pertinent key scholarship on adaptation studies and the comics studies field specifically. -

Terrible Old Games Youve Probably Never Heard of Free

FREE TERRIBLE OLD GAMES YOUVE PROBABLY NEVER HEARD OF PDF Stuart Ashen | 192 pages | 01 Mar 2016 | Cornerstone | 9781783522569 | English | London, United Kingdom Stuart Ashen Breaks Crowdfunding Records – TenEighty — Internet culture in focus Launched in May, the campaign is currently the top-funded book on the Unbound website. Click here to learn more! TenEighty uses cookies. Like most websites, TenEighty uses functional cookies and external scripts. You can choose whether or not to opt into those here. If you want to change your settings in the future, you can return to this menu via Terrible Old Games Youve Probably Never Heard of. NOTE: These settings will only apply to the browser and device you are currently using. We use Google AdSense to generate revenue from visits to our website. Google will display ads that it believes are relevant to you based on your browsing history, and we will earn a small amount of money from any interactions you have with them. You can find out more about this and return to this menu if you want to change your settings via teneightymagazine. This helps us learn a bit about who our readers are, what TenEighty content they are interested in, and how they consume it. We have chosen to use the IP Anonymization option so that your IP address and specific location are never recorded. The data collected by Google Analytics is retained indefinitely, but none of it is personally identifiable, and it is not made available to any third parties. It also lets us know how many people are using the site at any given moment, which allows us to identify and deal with traffic spikes. -

Dark Souls: Let's Be Honest

culture, debate, mechanics [http://howtonotsuckatgamedesign.com/?p=3538] , November 6, 2011 [http://howtonotsuckatgamedesign.com/?p=3538] by Anjin Anhut. Tweet 25 Like 80 4 Sharre StumbleUpon This article is filed under game criticism. Dark Souls: Let’s Be Honest If you like it, that’s great, buy it, share it, hug it. You go! But don’t give me that crap of Dark Souls being a worthwhile game and whoever doesn’t like it is either not as bad-ass, patient or resilient as you. Or simply doesn’t get it. That cake, son, is a lie. Hard Done Right Before I dive into Dark Souls, I’d like to tell you about Vanquish. Vanquish is a very well crafted action game and it has multiple difficulty settings. God Hard is, like the name implies, hard as hell. The high difficulty in Vanquish comes with carefully balanced game mechanics, spot on controls and tight play-testing. The player is always in full control of his avatar and has a wide range of offensive and defensive options at his disposal. The difficult scenes are a result of well done enemy AI, well designed and diverse enemy classes plus thought out level design and arenas. A game like Vanquish on God Hard is a punishing experience. But the strategic options to try out, the levels to exploit and the search for weak spots in enemies keeps the gameplay from getting repetitive, even if you have to retry a checkpoint multiple times. The most important aspect is the fact, that the game just works smooth. -

O Arquétipo Do Jornalista Nas Hqs Do Superman

UNIVERSIDADE DE BRASÍLIA FACULDADE DE COMUNICAÇÃO DEPARTAMENTO DE JORNALISMO Paulo Victor Pereira Queiroz O arquétipo do jornalista nas HQs do Superman Brasília 2018 UNIVERSIDADE DE BRASÍLIA FACULDADE DE COMUNICAÇÃO DEPARTAMENTO DE JORNALISMO Paulo Victor Pereira Queiroz O arquétipo do jornalista nas HQs do Superman Monografia apresentada à Banca Examinadora da Faculdade de Comunicação da Universidade de Brasília, como requisito parcial para obtenção do grau de Bacharelado em Comunicação Social, com habilitação em Jornalismo. Orientador: Prof. Wagner Antônio Rizzo Brasília 2018 Paulo Victor Pereira Queiroz O arquétipo do jornalista nas HQs do Superman Monografia apresentada à Banca Examinadora da Faculdade de Comunicação da Universidade de Brasília, como requisito parcial para obtenção do grau de Bacharelado em Comunicação Social, com habilitação em Jornalismo. Aprovado em 04/07/2018. BANCA EXAMINADORA ___________________________________ Prof. Dr. Wagner Antônio Rizzo (Orientador) ___________________________________ Prof. Dr. Wladimir Ganzelevitch Gramacho ___________________________________ Prof. Dr. Solano dos Santos Nascimento ___________________________________ Profa. Dra. Suzana Guedes Cardoso (Suplente) Brasília, 2018 AGRADECIMENTOS Agradeço a Deus e a Nossa Senhora por se fazerem presentes iluminando minhas escolhas durante toda a minha vida. Aos meus pais Junior e Karina e à minha mãe Renata (in memoriam), pela dedicação incondicional, amor, carinho, incentivo diário e tantas coisas que eu não poderia descrever. Eu amo vocês. À minha irmã Amanda, por ser a melhor companhia e abaixar o volume sempre que eu pedi, fonte de inspiração e minha melhor amiga. Às minhas avós Maria Francisca, Mariquinha e Belks, pelas orações, e aos meus avôs Rui, Renato e Zé Bolo, pela referência, paciência e torcida. Ao meu orientador, professor doutor Wagner Rizzo, pela disponibilidade, aposta, empatia e empréstimo de material durante todo o semestre. -

No Frills in This New Feature, We Will Be Going Far Back Into the DP Archives and Looking at Some of Our Past Work

video game fanzine no frills In this new feature, we will be going far back into the DP archives and looking at some of our past work. We might add in commentary, correct errors that slipped through the cracks, poke fun at ourselves, or simply re-run an article that’s so entertaining we had to publish it again. Anyway, here it is, from issue number 1. Now -Ikari Warriors, Mat Mania and Mean 18 were all published by Atari, not the companies in parenthesis. -Pyromania never came out. -“Asteroids Deluxe” should really be “Asteroids.” -The European-only Sentinel was missing Those are the only errors for the entire list. It is quite an impressive list considering it is 18 years old. Micky Wright From the editor’s desk... Greetings again from New Jersey. Those of you far from Digital Press HQ probably wouldn’t paint a pretty picture of our home state. Can’t say I blame you. New Jersey has a rep for being industrial and all the things that go along with that descriptor: dirty, polluted, run-down, crime-ridden, dingy, bleak, etc. I love New Jersey. Was it strange to read those words? It was strange to type them. The reason I love New Jersey is that we have a little bit of everything here, or just a few miles out of state. Anywhere you want to go is within a 2-hour drive. Snow-capped mountains, sprawling pine forests, beach resorts, wildlife preserves, skyscrapers, small towns, shopping malls, country clubs, amusement parks...it’s all here. -

Doctoral Dissertation Template

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE THE AESTHETIC VALUE OF VIDEOGAMES: AN ANALYSIS OF INTERACTIVITY, GAMEPLAY, AND PLAYER PERFORMANCE A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By ZACHARY LEE JURGENSEN Norman, Oklahoma 2018 THE AESTHETIC VALUE OF VIDEOGAMES: AN ANALYSIS OF INTERACTIVITY, GAMEPLAY, AND PLAYER PERFORMANCE A DISSERTATION APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF PHILOSOPHY BY ______________________________ Dr. Sherri Irvin, Chair ______________________________ Dr. Hugh Benson ______________________________ Dr. Stephen Ellis ______________________________ Dr. Dean Hougen ______________________________ Dr. Martin Montminy © Copyright by ZACHARY LEE JURGENSEN 2018 All Rights Reserved. For my parents: Perry and Betty Jurgensen Acknowledgements This dissertation is the product of a long, demanding journey made possible by the continued support of my family, my wife, close friends, colleagues, and mentors. There undoubtedly will be someone I miss, but I am indebted and deeply grateful to the following people who helped shape me into the philosopher, gamer, and person capable of finishing this project: My father, Perry Jurgensen, for showing me the value of hard work; my mother, Betty Jurgensen, for encouraging my endless curiosity and love of knowledge; my friends, Rob Byer, Steve Dwyer, Casey Stull, and Mike Jordan for challenging me both literally and figuratively when it comes to playing and thinking about games; my wife, Trish Catalano for keeping me focused when my will and spirit were tested time and again; my undergraduate teachers, Gene Rice, Doug Drabkin, Stephen Tramel, and Ruth Tallman for turning a freshman student interested in arguing about religion into an aspiring philosopher; my graduate professors, Martin Montminy, Stephen Ellis, Chris Swoyer, Hugh Benson, and Ray Elugardo for teaching me how to properly engage in rigorous, disciplined philosophical thought and writing; and my dissertation committee for their continued patience and advice.