Genetically Engineered Fish and Seafood

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE CASE for FIRST AMENDMENT PROTECTION of BIOART in 2000

FREEDOM TO EXPRESS A BIOLOGICAL CONSTRUCT: THE CASE FOR FIRST AMENDMENT PROTECTION OF BIOART KEITH SYVERSON INTRODUCTION In 2000, contemporary artist Eduardo Kac made international headlines by partnering with scientists at the Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique (INRA), France where together they genetically engineered an albino rabbit to express an enhanced green fluorescent protein (GFP)1 so that the rabbit would glow green when exposed to blue light.2 The entire project from its conception to the final display was intended as an artistic experiment to challenge society’s views on animal experimentation and the selective breeding of pets.3 This type of work that merges art and biology is called “BioArt.” According to Eduardo Kac, BioArt “employs one or more of the following approaches: (1) the coaching of biomaterials into specific inert shapes or behaviors; (2) the unusual or subversive use of biotech tools and processes; (3) the invention or transformation of living organisms with or without social environmental integration."4 BioArt has arguably existed for centuries.5 For example, some commentators have described the primitive methods of brewing beer in the Old Kingdom as form of BioArt.6 Similarly, the artificial selection involved in agriculture has been viewed by some as a form of 1 Frances Stracey, Bio-art: The Ethics Behind the Aesthetics, 10 NATURE REVIEWS: MOLECULAR CELL BIOLOGY 496, 499 (2009). 2 Id. 3 Id. 4 Eduardo Kac, Art That Looks You in the Eye: Hybrids, Clones, Mutants, Synthetics, and Transgenics, in SIGNS OF LIFE 1, 18 (Eduardo Kac ed., MIT Press, 2007). 5 See Edgar DaSilva, Art, Biotechnology and the Culture of Peace, 7 ELECTRONIC JOURNAL OF BIOTECHNOLOGY 130, 131-32 (2004) (arguing that the brewing reliefs in Egypt during the Old Kingdom from 2650 BC are an example of BioArt). -

Genetically Modified, Red Fluorescent Zebrafish: Detection, Crossing

Journal of Environmental Biotechnology Vol. 8, No. 2, 105–110, 2008 Original paper (regular paper) Genetically Modifi ed, Red Fluorescent Zebrafi sh: Detection, Crossing, Inheritance of Red Fluorescence, and Tolerance to Low Temperatures KIMIKO AMANUMA*, NOBUYOSHI NAKAJIMA, AKIKO H. HASHIMOTO and YASUNOBU AOKI National Institute for Environmental Studies, 16–2 Onogawa, Tsukuba, Ibaraki 305–8506, Japan * TEL: +81–(0)29–850–2390 FAX: +81–(0)29–850–2588 * E-mail: [email protected] (Received; 28 September, 2008/Accepted; 10 October, 2008) Under Cartagena Protocol domestic law, genetically modifi ed (GM) fi sh have not yet received permission to be imported or sold in Japan. However, it is anticipated that ornamental, fl uorescent GM fi sh will be imported and sold prior to any offi cial process for evaluating their eff ects on biological diversity as GM organisms (GMO). Therefore, we have devised a method for detecting GM fi sh that utilizes PCR for the detection of replication origins of plasmids that generally exist as transgenes integrated in the GMOs’ chromosomes. Using red fl uorescent zebrafi sh (rfZF), sold in Japan, and rpsL GM ZF established by us, we demonstrated the feasibility of this method for detecting GMO. Next, we examined the biological characteristics of the GM rfZF. They were able to cross with non-GM ZF; the red fl uorescence was inherited by their progeny according to expected outcomes, based on Mendelian genetics. Examination of the low temperature tolerance of rfZF and non-GM fi sh indicated that the lethal, minimum temperature was the same for both fi sh (5°C). -

Genome As a Tool of Genetic Engineering: Application in Plant and Plant Derived Medicine

International Journal of Biotech Trends and Technology (IJBTT) – Volume 8 Issue 1- Jan - March 2018 Genome as a Tool of Genetic Engineering: Application in Plant and Plant Derived Medicine A.B.M. Sharif Hossain1,2 Musamma M. Uddin2 1Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Hail University, Hail, KSA 2Biotechnology Program, Institute of Biological Sciences, Faculty of Science, University of Malaya, 50603, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia introduce point mutations. Genetically modified Abstract organism (GMO) is considered as an organism that The study was conducted from different is generated through genetic engineering. The first modern research data to review the innovative GMOs were bacteria in 1973, GM mice were generated in 1974 [4]. Insulin-producing bacteria latest technology in the genomics and its were commercialized in 1982 and genetically application in Agriculture, biomedicinae and modified food has been sold since 1994. Glofish, the plant derived medicine. Application of genome first GMO designed as a pet, was first sold in the in genetic engineering and molecular United States December in 2003 [4]. Genetic biotechnology have been exhibited well. engineering biotechnology has been applied in Genetically Modified Organism (GMO), numerous fields including agriculture, industrial Agrobacterium mediated recombination (T- biotechnology, and medicine. Enzymes used in DNA) and genetic engineering using molecular laundry detergent and medicines such as insulin and Biotechnology in plant, medicine and human growth hormone are now manufactured in biomedicine have been highlighted from GM cells, experimental GM cell lines and GM animals such as mice or zebra fish are being used for technology based different research data. research purposes, and genetically modified Moreover, molecular biotechnology in crops have been commercialized [4]. -

The Bio Revolution: Innovations Transforming and Our Societies, Economies, Lives

The Bio Revolution: Innovations transforming economies, societies, and our lives economies, societies, our and transforming Innovations Revolution: Bio The The Bio Revolution Innovations transforming economies, societies, and our lives May 2020 McKinsey Global Institute Since its founding in 1990, the McKinsey Global Institute (MGI) has sought to develop a deeper understanding of the evolving global economy. As the business and economics research arm of McKinsey & Company, MGI aims to help leaders in the commercial, public, and social sectors understand trends and forces shaping the global economy. MGI research combines the disciplines of economics and management, employing the analytical tools of economics with the insights of business leaders. Our “micro-to-macro” methodology examines microeconomic industry trends to better understand the broad macroeconomic forces affecting business strategy and public policy. MGI’s in-depth reports have covered more than 20 countries and 30 industries. Current research focuses on six themes: productivity and growth, natural resources, labor markets, the evolution of global financial markets, the economic impact of technology and innovation, and urbanization. Recent reports have assessed the digital economy, the impact of AI and automation on employment, physical climate risk, income inequal ity, the productivity puzzle, the economic benefits of tackling gender inequality, a new era of global competition, Chinese innovation, and digital and financial globalization. MGI is led by three McKinsey & Company senior partners: co-chairs James Manyika and Sven Smit, and director Jonathan Woetzel. Michael Chui, Susan Lund, Anu Madgavkar, Jan Mischke, Sree Ramaswamy, Jaana Remes, Jeongmin Seong, and Tilman Tacke are MGI partners, and Mekala Krishnan is an MGI senior fellow. -

Guide to Biotechnology 2008

guide to biotechnology 2008 research & development health bioethics innovate industrial & environmental food & agriculture biodefense Biotechnology Industry Organization 1201 Maryland Avenue, SW imagine Suite 900 Washington, DC 20024 intellectual property 202.962.9200 (phone) 202.488.6301 (fax) bio.org inform bio.org The Guide to Biotechnology is compiled by the Biotechnology Industry Organization (BIO) Editors Roxanna Guilford-Blake Debbie Strickland Contributors BIO Staff table of Contents Biotechnology: A Collection of Technologies 1 Regenerative Medicine ................................................. 36 What Is Biotechnology? .................................................. 1 Vaccines ....................................................................... 37 Cells and Biological Molecules ........................................ 1 Plant-Made Pharmaceuticals ........................................ 37 Therapeutic Development Overview .............................. 38 Biotechnology Industry Facts 2 Market Capitalization, 1994–2006 .................................. 3 Agricultural Production Applications 41 U.S. Biotech Industry Statistics: 1995–2006 ................... 3 Crop Biotechnology ...................................................... 41 U.S. Public Companies by Region, 2006 ........................ 4 Forest Biotechnology .................................................... 44 Total Financing, 1998–2007 (in billions of U.S. dollars) .... 4 Animal Biotechnology ................................................... 45 Biotech -

Go with the Glow: Fluorescent Proteins to Light Transgenic Organisms

Review TRENDS in Biotechnology Vol.24 No.4 April 2006 Go with the glow: fluorescent proteins to light transgenic organisms C. Neal Stewart, Jr University of Tennessee, Department of Plant Sciences, Knoxville, TN 37996 USA Once a biological novelty known for their role in zebrafish [8] and the frog Xenopus laevis [9] were bioluminescence, fluorescent proteins (FPs) from marine transformed with GFP variants yielding visible green invertebrates have revolutionized the life sciences. fluorescence. FPs quickly transcended science to be used Organisms from all kingdoms have been transformed in ornamental fish and even iconic works of art. The most with the Aequorea victoria green fluorescent protein infamous of these is ‘Alba’, the GFP bunny commissioned (GFP), and biotechnology has been advanced by the use by the artist Eduardo Kac. The erstwhile albino rabbit was of FPs. This article reviews the current uses of FPs in engineered with GFP to yield a striking fluorescent whole transgenic organisms and genomics and looks phenotype (Figure 1a), which was a focal point of the beyond GFP to the complete color palette and spectral Eighth Day art exhibit, where art and biotechnology properties afforded by FPs from other marine organisms. intersected (www.ekac.org/gfpbunny.html#gfpbunnyan- Coupled with electronic devices for visualizing and chor). The transgenic rhesus monkey ‘ANDi’ [10] was quantifying FPs, recently cloned FP genes might be also iconic (at least from a news perspective) not because it useful for the ecological monitoring of transgenic had a macroscopically fluorescent body but simply because organisms in the environment. Therefore, this review it was the first reported GFP transgenic primate – also addresses the in vivo labeling of organisms with an obviously reporters and the public had a closer taxonomic emphasis on plants. -

Swimming Upstream: the Eedn to Resolve Inconsistency in the FDA's Fishy Regulatory Scheme Kelsie Kelly

Journal of Law and Policy Volume 27 | Issue 1 Article 5 Fall 10-1-2018 Swimming Upstream: The eedN to Resolve Inconsistency in the FDA's Fishy Regulatory Scheme Kelsie Kelly Follow this and additional works at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/jlp Part of the Agriculture Law Commons, Food and Drug Law Commons, and the Science and Technology Law Commons Recommended Citation Kelsie Kelly, Swimming Upstream: The Need to Resolve Inconsistency in the FDA's Fishy Regulatory Scheme, 27 J. L. & Pol'y 185 (2018). Available at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/jlp/vol27/iss1/5 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at BrooklynWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Law and Policy by an authorized editor of BrooklynWorks. S"I11IN4 $PS%&6,17 %36 N66) %( &6S(L#6 IN*(NSIS%6N*0 IN %36 5),'S 5IS30 &64$L,%(&0 S*3616 Kelsie Kelly* The citizens of the United States rely on the federal government to maintain the safety of their food through effective regulation. As the technology used to develop food has advanced, the outermost limits of the current regulatory framework are being tested. The result has been a circuitous and ineffective attempt to regulate transgenic organisms, intended for human consumption, using multiple agencies and a patchwork of laws. The ability to incorporate DNA from nearly any organism into the genome of another provides immense potential for innovative new food products, but may also allow for unintended health and environmental consequences. Proper regulation of genetically engineered organisms is necessary in order to safely and effectively utilize biotechnology to benefit the American people. -

What Would You Do with a Fluorescent Green Pig: How Novel

What Would You Do with a Fluorescent Green Pig?: How Novel Transgenic Products Reveal Flaws in the Foundational Assumptions for the Regulation of Biotechnology Sheryl Lawrence* The Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetics Act (FDCA) and the Coordinated Framework for the Regulation of Biotechnology are the primary federal tools for oversight of the products of genetic modification. Since their enactment, tremendous advancements in biotechnology have resulted in the creation of novel transgenic organisms, significantly unlike any pre-existing life form. The innovative nature of these transgenicproducts challenges fundamental assumptions of the FDCA and the CoordinatedFramework. The first of these key assumptions is that the categories of "foods" and "drugs" are cleanly separable,and thus can be regulatedthrough entirely different path ways. The FDCA and the CoordinatedFramework also assume that genetically modified products do not pose inherent risks of environmental harm requiring regulatory oversight. On this basis, the United States has established a bifurcated system for the regulation of foods and drugs, in which drugs are subjected to much more rigorous scrutiny than food or industrial products. However, basing risk assessment for a novel transgenicorganism on this classificationplaces far too much weight on a distinction that is oblivious to the innate features of the transgenic product that present potential risk. Many transgenic organisms will present multiple usage possibilities, whether food, drug, or industrial, Copyright © 2007 by the Regents of the University of California. Sheryl Lawrence, University of California, Berkeley, Boalt Hall School of Law, J.D., 2006. This paper was awarded the Ellis J. Harmon Environmental Law Writing Award and the Alvin and Sadie Landis prize for government law writing in 2006, by panels composed of Boalt's environmental law faculty and practitioners. -

Animal Health and Welfare Alison Van Eenennaam, Ph.D

Animal Health and Welfare Alison Van Eenennaam, Ph.D. Cooperative Extension Specialist Animal Biotechnology and Genomics Department of Animal Science University of California, Davis, USA [email protected] @BioBeef Blog: http://biobeef.faculty.ucdavis.edu http://animalscience.ucdavis.edu/animalbiotech Van Eenennaam BIO 9/21/2016 Animal Genomics and Biotechnology Education https://youtu.be/C0MBl0BANHg Animal biotech is often associated with only one application BIO 9/21/2016 Animal Biotechnology and Genomics Education Sustainability implications of land-based AquAdvantage aquaculture √ More efficient: Less feed to produce a serving of fish √ Less disease spread to wild populations √ Decreased use of antibiotics BIO 9/21/2016 Animal Biotechnology and Genomics Education Genetically engineered Glofish Pigs as organ donors - xenotransplantation • http://www.glofish.com BIO 9/21/2016 Animal Genomics and Biotechnology Education Genetic improvement (permanent, cumulative) as a solution to animal disease rather than chemicals BIO 9/21/2016 The influenza pandemic of 1918 killed between 20-40 million people - more than died in WWI BIO 9/21/2016 Animal Genomics and Biotechnology Education GE Chickens That Don't Transmit Bird Flu Breakthrough could prevent future bird flu epidemics Science 331:223-226. 2011 www.roslin.ed.ac.uk/public-interest/gm-chickens BIO 9/21/2016 Animal Genomics and Biotechnology Education TRYPANOSOMIASIS (African sleeping sickness) in SUB-SAFARAN AFRICA • Several thousand people die of African sleeping sickness and 3 -

The Use of Fluorescence in Genetically Modified Animals

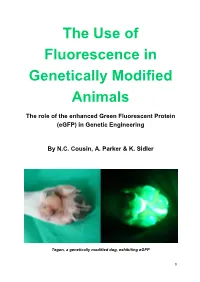

The Use of Fluorescence in Genetically Modified Animals The role of the enhanced Green Fluorescent Protein (eGFP) in Genetic Engineering By N.C. Cousin, A. Parker & K. Sidler Tegon, a genetically modified dog, exhibiting eGFP 0 Contents Preface 2 Introduction 2 Description of technique 4 Documentation of visited research institutions 6 Interview 7 Discussion 8 Summary 9 References 10 Figure sources 11 1 Preface When we were informed that we had to write a paper about Genetic Engineering, the first thought that came to mind was “Ruppy”. Ruppy was the first ever transgenic dog. She was genetically engineered so that she would glow red under UV light. We were so interested in the fact that scientists could create such animals that we began to research Ruppy and came across Tegon. Tegon was another transgenic dog created by the same laboratory. Tegon, however, expressed the enhanced Green Fluorescent Protein (eGFP). On the cover you can see a picture of Tegon’s paws when exposed to UV light. The expression of eGFP is regulated by doxycycline, so that only when it is administered, the protein is expressed and the dog can glow when exposed to UV light. The more we heard about eGFP, the more interested we became in all its possible applications in medical and biological research. eGFP (or better: the gene which encodes for it) is mainly used as a reporter gene, which means it is attached to a gene of interest and through its expression this gene is monitored. Depending on how the new genetically engineered organism is “programmed”, it can be used in multiple ways. -

Environmental and Indirect Human Health Risk Assessment of the Glofish® Electric Green® Tetra and the Glofish® Long-Fin Elect

Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat National Capital Region Science Advisory Report 2018/027 ENVIRONMENTAL AND INDIRECT HUMAN HEALTH RISK ASSESSMENT OF THE GLOFISH® ELECTRIC GREEN® TETRA AND THE GLOFISH® LONG-FIN ELECTRIC GREEN® TETRA (GYMNOCORYMBUS TERNETZI): A TRANSGENIC ORNAMENTAL FISH Figure 1. Some variants of Gymnocorymbus ternetzi available in the ornamental pet trade worldwide (a, b, d, e), and notified transgenic variants (c, f). Wild-type Black Tetra (a, d), White Tetra (b, e) and CGT2016 Electric Green® tetra (c, f) showing normal and long- fin variants, respectively. Taken from commercial websites www.petsmart.com (a, b), www.glofish.com (c, f) and www.segrestfarms.com (d, e). Context: The biotechnology provisions of the Canadian Environmental Protection Act (CEPA) take a preventative approach to environmental protection by requiring all new living organism products of biotechnology, including genetically engineered fish, to be notified and assessed prior to their import into Canada or manufacture in Canada, to determine whether they are “toxic” or capable of becoming “toxic”. Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC) and Health Canada (HC) are mandated to conduct all risk assessments under CEPA. On July 5, 2017 a notification under the NSNR(O) was submitted by GloFish LLC to ECCC for the GloFish® Electric Green® Tetra (CGT2016), a genetically engineered white variant of the Black Tetra (Gymnocorymbus ternetzi). Under a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) between the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO), ECCC and HC, DFO conducts an environmental risk assessment as advice, provides this advice to ECCC, and collaborates with HC to conduct an indirect human health risk assessment for any fish products of biotechnology notified under CEPA and the New Substances Notification Regulations (Organisms) [NSNR(O)]. -

Here's the List

List of Genetically Modified Organisms for 8th grade research project May 2017 1. lavender-colored carnations- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dianthus_caryophyllus#Colors 2. blue roses- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blue_rose 3. glowing fish- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/GloFish 4. golden rice- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Golden_rice 5. salmon- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Genetically_modified_salmon 6. insect- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Genetically_modified_insect 7. MON 810- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/MON_810 8. Amflora- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amflora 9. Roundup Ready Soybean- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roundup_ready_soybean 10. Flavr Savr- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flavr_savr 11. Wheat- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Genetically_modified_wheat 12. Mouse- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Knockout_mouse 13. Pig- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Enviropig 14. Bull- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herman_the_Bull 15. Sheep- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dolly_the_sheep 16. Ice-minus bacteria- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ice-minus_bacteria 17. supermice- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Metabolic_supermice 18. oncomouse- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oncomouse 19. rat- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Knockout_rat 20. goats- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/BioSteel 21. green fluorescence- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Green_fluorescent_protein 22. Ruppy- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ruppy 23. mosquito- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aedes_aegypti 24. corn- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SmartStax 25. poplar tree- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Genetically_modified_tree 26. dog- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Snuppy 27. rice fish- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oryzias_latipes 28. medicine- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ATryn 29. papaya- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carica_papaya 30.