The Description and Indexing of Editorial Cartoons: an Exploratory Study Christopher Ryan Landbeck

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Want to Have Some Fun with Tech and Pol Cart

Want To Have Some Fun With Technology and Political Cartoons? Dr. Susan A. Lancaster Florida Educational Technology Conference FETC Political and Editorial Cartoons In U.S. History http://dewey.chs.chico.k12.ca.us/edpolcart.html • Political cartoons are for the most part composed of two elements: caricature, which parodies the individual, and allusion, which creates the situation or context into which the individual is placed. • Caricature as a Western discipline goes back to Leonardo da Vinci's artistic explorations of "the ideal type of deformity"-- the grotesque-- which he used to better understand the concept of ideal beauty 2 • Develop Cognitive • Historical and Thinking and Higher Government Events Levels of Evaluation, • Group Work Analysis and Synthesis • Individual Work • Create Student • Current Events Drawings and Interpretations • Sports Events • Express Personal • Editorial Issues Opinions • Foreign Language and • Real World Issues Foreign Events • Visual Literacy and • Authentic Learning Interpretation • Critical Observation and Interpretation • Warm-up Activities • Writing Prompts 3 • Perspective A good editorial cartoonist can produce smiles at the nation's breakfast tables and, at the same time, screams around the White House. That's the point of cartooning: to tickle those who agree with you, torture those who don't, and maybe sway the remainder. 4 http://www.newseum.org/horsey/ Why include Political Cartoons in your curriculum? My goal was to somehow get the students to think in a more advanced way about current events and to make connections to both past and present Tammy Sulsona http://nieonline.com/detroit/cftc.cfm?cftcfeature=tammy 5 Cartoon Analysis Level 1 Visuals Words (not all cartoons include words) List the objects or people you see in the cartoon. -

Food of Love Folio Manhattan

Join us for Cerddorion’s 20th Anniversary Season! Our twentieth season launches Friday, November 14 at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Carroll ERDDORION Gardens, Brooklyn. Our Manhattan concert date will be finalized soon. In March 2015, we will mark our 20th anniversary with a special concert, including the winners VOCAL ENSEMBLE of our third Emerging Composers Competition. The season will conclude with our third concert C late in the spring. Be sure to check www.Cerddorion.org for up-to-date information, and keep an eye out for James John word of our special anniversary gala in the spring! Artistic Director !!! P RESENTS Support Cerddorion Ticket sales cover only a small portion of our ongoing musical and administrative expenses. If you would like to make a tax-deductible contribution, please send a check (payable to Cerddorion NYC, Inc.) to: The Food of Love Cerddorion NYC, Inc. Post Office Box 946, Village Station HAKESPEARE IN SONG New York, NY 10014-0946 S I N C OLLABORATION WITH !!! HE HAKESPEARE OCIETY For further information about Cerddorion Vocal Ensemble, please visit our web site: T S S Michael Sexton, Artistic Director WWW.CERDDORION.ORG Join our mailing list! !!! or Follow us on Twitter: @cerddorionnyc Sunday, June 1 at 3pm Sunday, June 8 at 3pm or St. Paul’s Episcopal Church St. Ignatius of Antioch Like us on Facebook 199 Carroll Street, Brooklyn 87th Street & West End Avenue, Manhattan THE PROGRAM DONORS Our concerts would not be possible without a great deal of financial assistance. Cerddorion would like to Readings presented by Anne Bates and Chukwudi Iwuji, courtesy of The Shakespeare Society thank the following, who have generously provided financial support for our activities over the past year. -

Part Enon - Vol

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar The Parthenon University Archives Fall 11-4-1987 The Parthenon, November 4, 1987 Marshall University Follow this and additional works at: https://mds.marshall.edu/parthenon Recommended Citation Marshall University, "The Parthenon, November 4, 1987" (1987). The Parthenon. 2505. https://mds.marshall.edu/parthenon/2505 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the University Archives at Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Parthenon by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ---- - --~------. ---------- --------- - --- ----- --Wednesday-------------------------- November 4, 1987 The Part enon - Vol. 89, No. 32 Marshall University's student newspaper Huntington, W.Va. BOR passes budget - Request to go to Legislature for consideration next session Northern Community Coll~ge at Wheel By SUSAN K. LAMBERT ing, were presented two proposals, one and KAREN E. KLEIN of$253 million and one of$243 million. Reporters The board split the vote 5-5 before Board President Louis J. Costanzo cast The Board of Regents approved Tues the deciding vote in favor of the lesser ay a $243 million budget proposal for amount. higher education to be presented to the Regent Tom Craig of Huntington, who Legislature for the 1988-89 fiscal year. was critical of the higher amount, said The approved request represents a 21 a request for more money would be percent increase over the $200 million "pinned on hopes that somehow there budget this year. It would fund just are revenues out there that can be mar half of what is needed to meet the min shaled into our coffers." imum salary levels for college and uni Included in the proposal is a request versity employees. -

The Pulitzer Prizes 2020 Winne

WINNERS AND FINALISTS 1917 TO PRESENT TABLE OF CONTENTS Excerpts from the Plan of Award ..............................................................2 PULITZER PRIZES IN JOURNALISM Public Service ...........................................................................................6 Reporting ...............................................................................................24 Local Reporting .....................................................................................27 Local Reporting, Edition Time ..............................................................32 Local General or Spot News Reporting ..................................................33 General News Reporting ........................................................................36 Spot News Reporting ............................................................................38 Breaking News Reporting .....................................................................39 Local Reporting, No Edition Time .......................................................45 Local Investigative or Specialized Reporting .........................................47 Investigative Reporting ..........................................................................50 Explanatory Journalism .........................................................................61 Explanatory Reporting ...........................................................................64 Specialized Reporting .............................................................................70 -

What Inflamed the Iraq War?

Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism Fellowship Paper, University of Oxford What Inflamed The Iraq War? The Perspectives of American Cartoonists By Rania M.R. Saleh Hilary Term 2008 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to express my deepest appreciation to the Heikal Foundation for Arab Journalism, particularly to its founder, Mr. Mohamed Hassanein Heikal. His support and encouragement made this study come true. Also, special thanks go to Hani Shukrallah, executive director, and Nora Koloyan, for their time and patience. I would like also to give my sincere thanks to Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, particularly to its director Dr Sarmila Bose. My warm gratitude goes to Trevor Mostyn, senior advisor, for his time and for his generous help and encouragement, and to Reuter's administrators, Kate and Tori. Special acknowledgement goes to my academic supervisor, Dr. Eduardo Posada Carbo for his general guidance and helpful suggestions and to my specialist supervisor, Dr. Walter Armbrust, for his valuable advice and information. I would like also to thank Professor Avi Shlaim, for his articles on the Middle East and for his concern. Special thanks go to the staff members of the Middle East Center for hosting our (Heikal fellows) final presentation and for their fruitful feedback. My sincere appreciation and gratitude go to my mother for her continuous support, understanding and encouragement, and to all my friends, particularly, Amina Zaghloul and Amr Okasha for telling me about this fellowship program and for their support. Many thanks are to John Kelley for sharing with me information and thoughts on American newspapers with more focus on the Washington Post . -

Selecting a Topic

Lesson Comic Design: 1 Selecting a Topic Time Required: One 40-minute class period to share some of their topic ideas Materials: sample comic strips, Student Worksheet 1 with the class. At the end of the Comic Design: Story and Character Creation, blank class discussion, ask each student to paper, pens/pencils have a single topic in mind for their comic strip. LESSON STEPS 6 Download Student Worksheet 1 Comic Design: Story 1 Ask students to name some comic strips that they and Character Creation from www.scholastic.com like or read. Distribute samples of current comics. /prismacolor and distribute to students. Tell You can cut comics out of a newspaper or look for students that their comic should tell a story in three free comics online through websites such as panels that is related to their chosen topic. The www.gocomics.com. story should follow a simple “arc”—which has a 2 Have students read the comic samples. Then ask beginning (the first panel), a middle (the second students to describe what they think makes for a panel), and a conclusion (the final panel). Encourage good comic. Write their responses on the board. students to look at the comic samples and talk with Answers may include: funny, well-drawn, smart, fellow students about their story arcs for inspiration. or suspenseful. Tell students that comic strips are 7 Have students complete Part I of the student a type of cartoon that tells a story. As the students worksheet. This will help them to develop their topic have noted in their descriptions, these stories are and the story that they want to tell. -

Anti-Americanism and the Rise of World Opinion: Consequences for the US National Interest Monti Narayan Datta Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-03232-3 - Anti-Americanism and the Rise of World Opinion: Consequences for the US National Interest Monti Narayan Datta Index More information Index Adidas-Salomon legitimacy of 45, 57, 80 comparative consumer study 84–9 and overseas image 191–3 European sales 88 and public diplomacy 191–3 Afghanistan relaxation 4 American foreign policy 4 and tourism 3–4 ISAF (International Security Assistance and unilateralism 3, 8–9, 36–7 Force) 4, 160–70 and world opinion 191 Obama effect on war 159–70 American national interest support for United States 20, 159–63 and anti-Americanism 13–15 troop contributions to ISAF 164–8 and decision-makers 13 troops variable 162–70 measurement of 13–14 alliance variable 64, 72, 77, 80, 133–7 policy objectives in 13–14 America American overseas wars, support for attention to interests of other countries 15–17, 146–7 see also coalition 35 support; First Gulf War (1991); Iraq credit rating 182 war (2003) culture, and anti-Americanism 3, 6, 10, American unipolarity/multipolarity 37–8, 112–14 175, 187 declining world status 181–3 American voters 23 economic power 185 analytic framework description 15–18 exceptionalism 45–6 anti-Bushism, 131–2, 149 see also Bush favorable opinions toward 62, 152, anti-great powerism 187–90 194–229 Arab public opinion 26–7 financial status 182–3 Arab Street 26 Gulf wars costs 119–26 Argentina higher education 108, 185–7 on Iraq war 145–6 innovation, and economic strength 185 on Obama effect 172 military spending 185 Armitage, Richard 57 multilateralism -

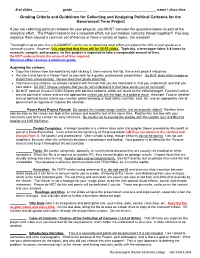

If You Are Collecting Political Cartoons for Your Projects, You MUST Consider the Questions Below As Part of the Analytical Effort

# of slides ________ grade _______ ______________________________ name / class time Grading Criteria and Guidelines for Collecting and Analyzing Political Cartoons for the Government Term Project If you are collecting political cartoons for your projects, you MUST consider the questions below as part of the analytical effort. The Project needs to be a complete effort, not just random cartoons thrown together!! You may organize them around a common set of themes or have a variety of topics. Be creative!! The length is up to you; it is a JUDGMENT call for you to determine what effort you expend for 20% of your grade as a semester project. However, it is expected that there will be 35-55 slides. Typically, a term paper takes 6-8 hours to research, compile, and prepare; so this project is expected to take a comparable amount of time. Do NOT underestimate the amount of time required. Minimum effort receives a minimum grade. Acquiring the cartoon: Copy the cartoon from the website by right clicking it, then move to the Ppt. frame and paste it into place. Re-size it and format in Power Point as you wish for a quality, professional presentation. Do NOT stretch the images or distort them unnecessarily. No one likes their photo stretched. You have many choices, so choose cartoons with themes that you are interested in, that you understand, and that you care about. Do NOT choose cartoons that you do not understand or that have words you do not know!! Do NOT confuse funnies/COMICS/jokes with political cartoons, which are found on the editorial page!! Funnies/Comics are not political in nature and are not appropriate unless you link the topic to a political issue. -

Leonie Scott-Matthews Appointed an OBE for Work on Pentameters Theatre and Services to Hampstead

New Year's Honours: Leonie Scott-Matthews appointed an OBE for work on Pentameters Theatre and services to Hampstead PUBLISHED: 22:30 27 December 2019 | UPDATED: 16:57 28 December 2019 Harry Taylor Leonie Scott-Matthews, who founded Pentameters Theatre in 1968 and has run it ever since, has been given the gong for services to British Theatre and services to the community in Hampstead. The 78-year-old, who has lived in the area since 1961, said she was "over the moon" at the news. She said: "Always doing things my way, the alternative way, it can be quite isolating. You think 'Am I right, or am I wrong?'. I've done it in a unique way, single handedly. "We've had our ups and downs in the 51 years we've run it, with no financial aid, but we've made it work." Ms Scott-Matthews started the theatre after holding poetry sessions in the cellar of the Freemasons Arms in Downshire Hill. She then held performances in a temporary home in the former Haverstock Tavern, before making the final move to Pentameters home above the Horseshoe Pub in Heath Street where it has remained ever since. She lives a stone's throw away with her partner Godfrey Old, with whom she has a 31-year-old daughter, Alice. She grew up in Mapperley near Nottingham before escaping to the bright lights of London and the Royal Academy of Music and Drama in the 1960s. She said: "When I was in drama school in the early 1960s I fell in love with Hampstead. -

Film Culture in Transition

FILM CULTURE IN TRANSITION Exhibiting Cinema in Contemporary Art ERIKA BALSOM Amsterdam University Press Exhibiting Cinema in Contemporary Art Exhibiting Cinema in Contemporary Art Erika Balsom This book is published in print and online through the online OAPEN library (www.oapen.org) OAPEN (Open Access Publishing in European Networks) is a collaborative in- itiative to develop and implement a sustainable Open Access publication model for academic books in the Humanities and Social Sciences. The OAPEN Library aims to improve the visibility and usability of high quality academic research by aggregating peer reviewed Open Access publications from across Europe. Sections of chapter one have previously appeared as a part of “Screening Rooms: The Movie Theatre in/and the Gallery,” in Public: Art/Culture/Ideas (), -. Sections of chapter two have previously appeared as “A Cinema in the Gallery, A Cinema in Ruins,” Screen : (December ), -. Cover illustration (front): Pierre Bismuth, Following the Right Hand of Louise Brooks in Beauty Contest, . Marker pen on Plexiglas with c-print, x inches. Courtesy of the artist and Team Gallery, New York. Cover illustration (back): Simon Starling, Wilhelm Noack oHG, . Installation view at neugerriemschneider, Berlin, . Photo: Jens Ziehe, courtesy of the artist, neugerriemschneider, Berlin, and Casey Kaplan, New York. Cover design: Kok Korpershoek, Amsterdam Lay-out: JAPES, Amsterdam isbn e-isbn (pdf) e-isbn (ePub) nur / © E. Balsom / Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. -

H-Diplo Roundtable Review, Vol. X, No. 27

2009 h-diplo H-Diplo Roundtable Review Roundtable Editors: Thomas Maddux and Diane www.h-net.org/~diplo/roundtables Labrosse Volume X, No. 27 (2009) Roundtable Web Editor: George Fujii Published on 31 July 2009; Introduction by Thomas Maddux reissued on 6 August 2009; Reviewers: John M. Cooper, Michael C. Desch, Walter updated 7 April 2013§ Hixson, Erez Manela, Robert W. Tucker G. John Ikenberry, Thomas J. Knock, Anne-Marie Slaughter, and Tony Smith. The Crisis in American Foreign Policy: Wilsonianism in the Twenty-first Century. Princeton University Press, 2009. Stable URL: http://www.h-net.org/~diplo/roundtables/PDF/Roundtable-X-27.pdf Contents Introduction by Thomas Maddux, California State University, Northridge.............................. 2 Review by John M. Cooper, University of Wisconsin-Madison ................................................ 8 Review by Michael C. Desch, University of Notre Dame ........................................................ 13 Review by Walter Hixson, University of Akron ....................................................................... 21 Review by Erez Manela, Harvard University ........................................................................... 25 Review by Robert W. Tucker, Professor Emeritus, The Johns Hopkins University ................. 29 Response by Thomas J. Knock, Southern Methodist University ............................................ 33 Response by Tony Smith, Cornelia M. Jackson Professor of Political Science, Tufts University37 [§Correctly classifies Erez Manela review as a review and not a response]. Copyright © 2009 H-Net: Humanities and Social Sciences Online. H-Net permits the redistribution and reprinting of this work for non-profit, educational purposes, with full and accurate attribution to the author(s), web location, date of publication, H-Diplo, and H-Net: Humanities & Social Sciences Online. For other uses, contact the H-Diplo editorial staff at [email protected]. H-Diplo Roundtable Reviews, Vol. -

April 2010 Quarterly Program Topic Report

April 2010 Quarterly Program Topic Report Category: Aging NOLA: SMIT 000000 Series Title: Smitten Length: 30 minutes Airdate: 4/19/2010 1:30:00 AM Service: PBS Format: Other Segment Length: 00:26:46 Meet Rene: at age 85, this unusual art collector continues to search for the work of northern California artists, hoping to make his next great discovery. SMITTEN follows Rene as he opens his private collection to the public, displaying the work without wall labels, so that people are empowered to interact with the art in a direct, personal, and more democratic way. Category: Agriculture NOLA: NOVA 003603 Series Title: NOVA Episode Title: Rat Attack Length: 60 minutes Airdate: 4/4/2010 12:00:00 PM Service: PBS Format: Documentary Segment Length: 00:56:46 Every 48 years, the inhabitants of the remote Indian state of Mizoram suffer a horrendous ordeal known locally as mautam. An indigenous species of bamboo, blanketing 30 percent of Mizoram's 8,100 square miles, blooms once every half-century, spurring an explosion in the rat population which feeds off the bamboo's fruit. The rats run amok, destroying crops and precipitating a crippling famine throughout Mizoram. NOVA follows this gripping tale of nature's capacity to engender human suffering, and investigates the botanical mystery of why the bamboo flowers and why the rats attack with clockwork precision every half-century. Category: Agriculture NOLA: AMDO 002301 Series Title: POV Episode Title: Food, Inc. Length: 120 minutes Airdate: 4/21/2010 8:00:00 PM Service: PBS Format: Documentary Segment Length: 01:56:46 In Food, Inc., filmmaker Robert Kenner lifts the veil on our nation's food industry, exposing the highly mechanized underbelly that's been hidden from the American consumer with the consent of our government's regulatory agencies, USDA and FDA.