Introduction Lamprey River Advisory Committee Archeological Survey Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Archeological Overview and Assessment Blow-Me-Down Farm

ARCHEOLOGICAL OVERVIEW AND ASSESSMENT BLOW-ME-DOWN FARM SAINT-GAUDENS NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE CORNISH, NEW HAMPSHIRE FINAL Prepared for: National Park Service Northeast Regional Archeology Program 115 John Street Lowell, MA 01852 Prepared by: James Lee, M.A., Principal Investigator Eryn Boyce, M.A., Historian JULY 2017 This page intentionally left blank. This page intentionally left blank. MANAGEMENT SUMMARY The following technical report describes and interprets the results of an archeological overview and assessment carried out at Blow-Me-Down Farm, part of the Saint-Gaudens National Historic Site in the Town of Cornish, Sullivan County, New Hampshire. The primary goals of this AOA were to: review existing archeological data; generate new archeological data through shovel testing and background research; catalog and assess known and potential archeological resources on this property; and make recommendations concerning the need and design of future studies (National Park Service 1997:25). The Blow-Me-Down Farm occupies a 42.6-acre parcel located between the Connecticut River to the west, New Hampshire Route 12A to the east and Blow-Me-Down Brook to the south. The property, which has a history extending back into the 18th century, served in the late 19th century as the summer home of Charles Beaman, a significant figure in the development of the Cornish Art Colony. The farm was purchased by the National Park Service in 2010 as a complementary property to the adjacent Saint-Gaudens National Historic Site listed in the National Register of Historic Places as a contributing element of the Saint-Gaudens National Historic Site Historic District in 2013. -

Quinebaug Solar, LLC Phase 1B Cultural Resources Report, Volume I

Kathryn E. Boucher Associate Direct Telephone: 860-541-7714 Direct Fax: 860-955-1145 [email protected] December 4, 2019 VIA ELECTRONIC MAIL AND FIRST CLASS MAIL Melanie A. Bachman Executive Director Connecticut Siting Council 10 Franklin Square New Britain, CT 06051 Re: Petition 1310 - Quinebaug Solar, LLC petition for a declaratory ruling that no Certificate of Environmental Compatibility and Public Need is required for the proposed construction, maintenance and operation of a 50 megawatt AC solar photovoltaic electric generating facility on approximately 561 acres comprised of 29 separate and abutting privately-owned parcels located generally north of Wauregan Road in Canterbury and south of Rukstela Road and Allen Hill Road in Brooklyn, Connecticut Dear Ms. Bachman: I am writing on above- d (“ ”) p d . d p d Resources Report (Exhi ). While Volume I was previously submitted to the Council as a bulk filing on November 12, 2019, the electronic version was inadvertently omitted. Please do not hesitate to contact the undersigned or David Bogan of this office (860-541-7711) should you have any questions regarding this submission. Very truly yours, Kathryn E. Boucher 81738234v.1 CERTIFICATION I hereby certify that on December 4, 2019, the foregoing was delivered by email and regular mail, postage prepaid, in accordance with § 16-50j-12 of the Regulations of Connecticut State Agencies, to all parties and intervenors of record, as follows: Troy and Megan Sposato 192 Wauregan Road Canterbury, CT 06331 [email protected] ______________________________ Kathryn E. Boucher Commissioner of the Superior Court 81738234v.1 NOVEMBER 2019 PHASE IB CULTURAL RESOURCES RECONNAISSANCE SURVEY OF THE PROPOSED QUINEBAUG SOLAR FACILITY AND PHASE II NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES TESTING AND EVALUATION OF SITES 19-35 AND 22-38 IN CANTERBURY AND BROOKLYN, CONNECTICUT VOLUME I PREPARED FOR: 53 SOUTHAMPTON ROAD WESTFIELD, MASSACHUSETTS 01085 PREPARED BY: P.O. -

Six FLOURING MILLS on MINNEHAHA CREEK

-f**^ ^^^^1 THESE RUINS of the old Godfrey water wheel have long since disappeared from the banks of Minnehaha Creek. The wheel is typ ical of the ones that powered the old- fashioned gristmills. 162 Minnesota History The Six FLOURING MILLS on MINNEHAHA CREEK Foster W. Dunwiddie MUCH HAS BEEN written about the flour-milhng in enjoy for fifty years — from 1880 to 1930. But in the dustry of Minneapolis and the history of St. Anthony pioneer days of Minnesota Territory, hauling grain to Falls. With development of the immense water power Minneapolis and St. Anthony was an arduous task, espe available at the falls, Minneapolis grew to become the cially during certain seasons of the year. Roads were flour-milling capital of the world, a position it was to poor and often impassable. This led quite naturally to the demand for small local flouring mills that were more readily accessible to the farmers, and a great many flour ^Lucde M. Kane, The Waterfad That Built a City, 99, 17,3 ing mills were erected throughout the territory.^ (St. Paul, 1966). The term "flour" is taken from the French In the nineteenth century, Minnehaha Creek, which term "fleur de farine, " which literally means "the flower, or still flows from Gray's Bay in Lake Minnetonka almost finest, of the meal." The word "flouring" or "flowering" was applied to miUs in this country as early as 1797. The suffix, directly eastward to the Mississippi River, was a stream "ing," was added to form a verbal noun, used in this case as an having sufficient flow of water to develop the necessary adjective to describe the type of mill. -

Gristmill Gazette 2019 Fall

The Gristmill Gazette Jerusalem Mill Village News & Notes Fall 2019 2811 Jerusalem Rd., Kingsville, MD www.jerusalemmill.org 410-877-3560 Upcoming Events All activities are in the village, unless otherwise indicated. Saturday, October 12th, 9 AM ‘til noon: Second Saturday Serve Volunteer Day. Come help us with a wide variety of tasks throughout the village. All tools, materials, equipment and protective gear will be provided. We’ll meet on the porch of the General Store or in the Tenant House across the street from the store, depending on the weather. Everyone is invited. Saturday, October 19th: Fairy Tales to Scary Tales and Family Haunted Trail. Halloween activities for all ages. Family activities (e.g. face painting, scarecrow making, treats, scavenger hunt, etc.) will occur from 1 PM to 4 PM. The haunted trail will be open until 8 PM. DONATIONS NEEDED: old long sleeve shirts and long pants to be used in scarecrow making. You can drop off donated items at the Jerusalem Mill Visitor Center on Saturdays or Mondays between 10 AM and 4 PM, on Sundays between 1 PM and 4 PM, or by calling the Visitor Center on 410-877-3560 to make special arrangements. Saturday, November 9th, 8 AM to 2 PM: Semi-annual Yard Sale. We’ll have a wide variety of household goods, books, DVDs, tools, equipment, toys, hardware, supplies, etc. If you have any items to donate, please call the Visitor Center at 410-877-3560 to arrange for drop-off, or simply bring them on the 9th (no chemicals or clothing). -

Benjamin Sawyer's Grist Mill

Benjamin Sawyer’s Grist Mill – 1794 A Brief Description of its History and Workings The Bolton Conservation Trust thanks Nancy Skinner for her generous donation of the land on which the foundations of the Sawyer Grist Mill are located and to the Bolton Historical Society for the important historical information about the Mill. Benjamin Sawyer’s Grist Mill - 1794 Benjamin Sawyer owned a saw mill and a grist mill relatively close to each other on the east side of Burnham Road and the north side of Main Street (Rt. 117). You are looking at the remains of the foundation of the grist mill. The saw mill was located on Great Brook to the right and behind the grist mill foundation. Samuel Baker had built the saw mill, a tanning yard and a small house just after his purchase of the 20 acres of land from John Osborne in 1750. The saw mill was powered by Great Brook on a seasonal (freshet) basis from a dammed pond to the west of Burnham Road. After passing through several other owners the land was purchased by Benjamin Sawyer in 1791 after which he built the grist mill just prior to 1794. Unlike the sawmill, the gristmill was powered throughout the year by water from West Pond which passed through culverts under Long Hill Road and the Great Road (now Main street). The water entered the mill from the side opposite to where you are standing and then ran under the building, through a wood channel (flume) and over what is believed (on the basis the height of the foundation) to have been an overshot water wheel and then into the channel (tailrace) to your left where it met Great Brook behind you. -

What Is a Grist Mill 2020

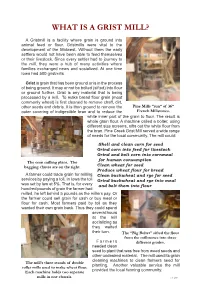

WHAT IS A GRIST MILL? A Gristmill is a facility where grain is ground into animal feed or flour. Gristmills were vital to the development of the Midwest. Without them the early settlers would not have been able to feed themselves or their livestock. Since every settler had to journey to the mill, they were a hub of many activities where families exchanged news and socialized. At one time Iowa had 500 gristmills. Grist is grain that has been ground or is in the process of being ground. It may or not be bolted (sifted) into flour or ground further. Grist is any material that is being processed by a mill. To make bread flour grain (most commonly wheat) is first cleaned to remove chaff, dirt, other seeds and debris. It is then ground to remove the Pine Mills “run” of 36” outer covering of indigestible bran and to reduce the French Millstones. white inner part of the grain to flour. The result is whole grain flour. A machine called a bolter, using different size screens, sifts out the white flour from the bran. Pine Creek Grist Mill served a wide range of needs for the local community. The mill could: Shell and clean corn for seed Grind corn into feed for livestock Grind and bolt corn into cornmeal for human consumption The corn milling plant. The bagging chutes are on the right. Clean wheat for seed Produce wheat flour for bread A farmer could trade grain for milling Clean buckwheat and rye for seed services by paying a toll. -

The Brainerd Mill and the Tellico Mills: the Development of Water- Milling in the East Tennessee Valley

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 6-1986 The Brainerd Mill and the Tellico Mills: The Development of Water- Milling in the East Tennessee Valley Loretta Ettien Lautzenheiser University of Tennessee, Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Lautzenheiser, Loretta Ettien, "The Brainerd Mill and the Tellico Mills: The Development of Water-Milling in the East Tennessee Valley. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 1986. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/4154 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Loretta Ettien Lautzenheiser entitled "The Brainerd Mill and the Tellico Mills: The Development of Water-Milling in the East Tennessee Valley." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in Anthropology. Charles H. Faulkner, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Jeff Chapman, Benita J. Howell Accepted for the Council: Carolyn -

Archaeological Explorations Phillips Gristmill Site Howell Living History

ARCHAEOLOGICAL EXPLORATIONS PHILLIPS GRISTMILL SITE HOWELL LIVING HISTORY FARM HOPEWELL TOWNSHIP, MERCER COUNTY NEW JERSEY P repared for: Mercer County Park Commission The Friends of Howell Living History Farm New Jersey Historical Commission Prepared by: James S. Lee Richard W. Hunter NOVEMBER 2012 MANAGEMENT SUMMARY In May and July of 2012 a program of archaeological exploration was carried out at the Phillips Gristmill Site in Pleasant Valley, Hopewell Township, Mercer County, New Jersey. This site lies within the Mercer County- owned property centered around the Howell Living History Farm and is contained within the Pleasant Valley Historic District, which is listed in the New Jersey and National Registers of Historic Places. The scope of work for these archaeological explorations involved limited background research, field survey, subsurface testing with the assistance of a backhoe, documentation of exposed remains, analysis of the research and field results, and preparation of a technical report. One weekend day was also set aside for public tours of the site during the course of the field investigation. This work was performed by Hunter Research, Inc. under contract to the Mercer County Park Commission. Project funding was provided by the County of Mercer supplemented by grants from the New Jersey Historical Commission and the Friends of Howell Living History Farm. The Phillips Gristmill is thought to have been originally established sometime between the late 1730s and circa 1770 by either John Phillips or his son Henry Phillips. The mill first appears in the documentary record in a tax ratable assessment of 1779. It passed out of Phillips family ownership in the 1830s, but remained in operation into the 1850s or 1860s. -

The Scene Played out Every Autumn Across

by Jason Jenkins he scene played out every autumn across rural America around the turn of the 20th century. Farmers hitched their wagons — loaded with the family and the season’s har- Tvest — and traveled to a nearby gristmill. Here, the crop they toiled all spring and summer to coax from the soil was transformed into flour or meal. In Ozark County, farmers from miles around brought their grain to Dawt Mill, a three-story roller mill perched high on the east bank of the North Fork of the White River. During the busy milling season, the mill operated 24 hours a day, and farm- ers would often wait days to “take their turn” on the millstone, spawning the expression used today when waiting to reach the front of a line. A trip to Dawt was more than an occasion to grind grain, though. Here in this thriving pioneer community, the women shopped in the general store and picked up letters at the post office. Chil- dren played games, skipped rocks on the millpond or fished while the men chatted about their crops, the weather and their plans for the coming year. With time and technological progress, however, the heyday of the water-powered gristmill ended about the time of World War II. Dawt Mill would continue to overlook the North Fork for more than a century, but by last fall, it seemed destined to succumb to the same fate as so To order a print of this photo, see page 29. many other gristmills whose names are now but a Once in danger of falling into the North Fork, a restored Dawt Mill is now home to Henegar’s Grist Mill Restaurant. -

Consolidated Word List: Words Appearing with Moderate Frequency (S-Z)

The Spelling Champ Consolidated Word List: Words Appearing with Moderate Frequency (S-Z) TheSpellingChamp.com Website by Cole Shafer-Ray TheSpellingChamp.com 2004 Scripps National Spelling Bee Consolidated Word List: Words Appearing with Moderate Frequency solemn solmizate somatotonic adj v adj ˌhÊOJL L L > F Gk marked by full realization and sing using a set of syllables to exhibiting a pattern of acceptance of all that is involved. denote the tones of a musical scale. aggressiveness, love of physical Donald looked solemn as he In the musical The Sound of Music, activity, vigor, and alertness.With apologized to the class. Maria composes a song called “Do his somatotonic personality,Brian Re Mi” to teach her young pupils gets more done before ninein the solemnly to solmizate. morning than most peopleget done all day. solenoglyph soloist n somatotype solenoid n n L > It + Ecf one who performs with no partner Gk Gk or associate. body type : physique.Considering a coil of wire commonly in the Charles is an occasional soloist in Phil’s thin, slightbuild, the form of a long cylinder that carries his school’s modern dance physician classified hissomatotype a current. performances. as ectomorphic. It took a long time to trace the power failure to a faulty solenoid. Solomonic sombra adj n soleprint Heb name L > Sp solfeggio marked by notable wisdom, the shady side or section of a reasonableness, or discretion bullfight arena. solicit especially under trying Richard was glad he had a seat in circumstances. the sombra. solicitude Naeem’s Solomonic solution to a n workplace disagreement earned sommelier him a reputation as a peacemaker. -

Colvin Run Mill Simple Machines Learning

Colvin Run Mill Historic Site Simple Machines 10017 Colvin Run Rd Great Falls, VA 22066 Learning Kit 703-759-2771 Introduction Inside: Thank you for scheduling a field trip to Colvin Run Mill Historic Educational 2 Site. We hope you and your Objectives students find your visit to be both educational and enjoyable. This Educational Themes 2 Learning Kit provides you with information to introduce your students to the site and to During the visit, your students will A Brief History of 3 reinforce concepts learned during go to three learning centers where Colvin Run Mill your visit. It includes Standards they will learn how simple machines of Learning objectives, made work easier and they will use Worksheet: 4 educational themes, a brief some simple machines. They will also 19th Century discover the inter-dependence of local Livelihoods history of the site, a list of vocabulary words, and rural economics, the impact of Oliver Evans’ 5 worksheets. Please feel free to geography on the development of Automated Mill: A adapt these materials to your communities in northern Virginia Symphony of Simple needs and to make copies of this and the importance of transportation Machines information. routes for commerce. Worksheet: 6 Simple Machines Make the Miller’s Job In the barn, Vocabulary List 7-8 students use four simple machines that made work easier in the days before electricity. In the mill, students In the general store, learn how grain was students discover a ground into flour or thriving commercial center cornmeal by the water- for the town and a hub of powered grinding social activities. -

Archeological Investigations at the Savacoal Property in Boston Village, Cuyahoga Valley National Park, Summit County, Ohio

ARCHEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATIONS AT THE SAVACOAL PROPERTY IN BOSTON VILLAGE, CUYAHOGA VALLEY NATIONAL PARK, SUMMIT COUNTY, OHIO By Ann C. Bauermeister Technical Report No. 128 NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Midwest Archeological Center ARCHEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATIONS AT THE SAVACOAL PROPERTY IN BOSTON VILLAGE, CUYAHOGA VALLEY NATIONAL PARK, SUMMIT COUNTY, OHIO By Ann C. Bauermeister Midwest Archeological Center Technical Report No. 128 NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Midwest Archeological Center United States Department of the Interior National Park Service Midwest Archeological Center Lincoln, Nebraska 2011 This report has been reviewed against the criteria contained in 43CFR Part 7, Subpart A, Section 7.18 (a) (1) and, upon recommendation of the Midwest Regional Office and the Midwest Archeological Center, has been classified as Available Making the report available meets the criteria of 43CFR Part 7, Subpart A, Section 7.18 (a) (1). ABSTRACT The Midwest Archeological Center (MWAC) conducted archeological inventory and evaluative testing efforts at the Savacoal property, in Cuyahoga Valley National Park (CUVA), during the 2001, 2002, and 2007 field seasons. The investigations resulted in the identification of two archeological sites, both located on land Tract 109-107 in Boston Village, Boston Township, Summit County, Ohio. Site 33SU419 is an historic artifact scatter associated with the Savacoal Barn on the east side of the parcel. A small prehistoric assemblage of two artifacts was also recovered from the site. Site 33SU423, the Hopkins House site, is a multicomponent prehistoric and historic site, with the latter assemblage attributed to the residential component on the west side of the lot. The archeological investigations were initiated in response to plans to rehabilitate and stabilize the barn (HS-487) and to adaptively restore the vacant house (HS-486).