Persuading the People

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RAF Wings Over Florida: Memories of World War II British Air Cadets

Purdue University Purdue e-Pubs Purdue University Press Books Purdue University Press Fall 9-15-2000 RAF Wings Over Florida: Memories of World War II British Air Cadets Willard Largent Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/purduepress_ebooks Part of the European History Commons, and the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Largent, Willard, "RAF Wings Over Florida: Memories of World War II British Air Cadets" (2000). Purdue University Press Books. 9. https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/purduepress_ebooks/9 This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. RAF Wings over Florida RAF Wings over Florida Memories of World War II British Air Cadets DE Will Largent Edited by Tod Roberts Purdue University Press West Lafayette, Indiana Copyright q 2000 by Purdue University. First printing in paperback, 2020. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America Paperback ISBN: 978-1-55753-992-2 Epub ISBN: 978-1-55753-993-9 Epdf ISBN: 978-1-61249-138-7 The Library of Congress has cataloged the earlier hardcover edition as follows: Largent, Willard. RAF wings over Florida : memories of World War II British air cadets / Will Largent. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-55753-203-6 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Largent, Willard. 2. World War, 1939±1945ÐAerial operations, British. 3. World War, 1939±1945ÐAerial operations, American. 4. Riddle Field (Fla.) 5. Carlstrom Field (Fla.) 6. World War, 1939±1945ÐPersonal narratives, British. 7. Great Britain. Royal Air ForceÐBiography. I. -

Download Target for Tonight Rules (English)

RULES OF PLAY TARGET FOR TONIGHT 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 Introduction 5.12 Heat Out and Frostbite 1.1 Game Rules 5.13 Oxygen Fires 1.2 Game Equipment 5.14 Loss of Oxygen and its Effects 1.3 Dice 1.4 Counter Identification 6.0. In the Target Zone 1.5 Game Forms and Boards 6.1 Bombing the Target 1.6 The Operational Tour of Duty 6.2 Low Altitude Bombing 1.7 Designer’s Note: The Anatomy of A Bombing Mission 6.3 (Optional Rule) Thermal Turbulence - Fire Bombing and Firestorms 2.0 Pre-Mission Steps 6.4 Pathfinders and the “Master Bomber” 2.1 Set-Up 6.5 The Turn Around - Heading Home 2.2 How to Win 2.3 The Twelve Campaigns Offered in Target for Tonight 7.0. Ending the Mission 2.4 Target Selection 7.1 Landing at Your Base 2.5 Selecting Your Bomber Type 7.2 Ditching (Landing) In Water 2.6 The Bomber Command Flight Log Gazetteer 7.3 Landing in Europe 2.7 The Electronics War 7.4 Bailing Out 2.8 The Bomber’s Crew Members 7.5 (Optional Rule) Awards 2.9 Crew Placement Board and Battle Board 7.6 (Optional Rule) Confirmation of German Fighters 2.10 Determine the Phase of The Moon Claimed Shot down By Your Gunners. 3.0 Starting the Mission 8.0 Post Mission Debriefing 3.1 Take-Off Procedure 9.0. Additional German Aircraft Rules 4.0 The Zones 9.1 (Optional Rule) The Vickers Wellington Bomber 4.1 Movement Defined 9.2 (Optional Rule) German Me-262 Jet Night Fighter 4.2 Weather in the Zone 9.3 (Optional Rule) Ta-154 A-0 Night Fighter. -

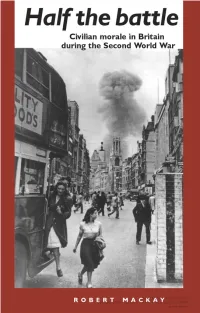

Robert Mackay - 9781526137425 Downloaded from Manchesterhive.Com at 09/24/2021 07:30:30PM Via Free Access HALF the BATTLE

Robert Mackay - 9781526137425 Downloaded from manchesterhive.com at 09/24/2021 07:30:30PM via free access HALF THE BATTLE Robert Mackay - 9781526137425 Downloaded from manchesterhive.com at 09/24/2021 07:30:30PM via free access prelim.p65 1 16/09/02, 09:21 Robert Mackay - 9781526137425 Downloaded from manchesterhive.com at 09/24/2021 07:30:30PM via free access prelim.p65 2 16/09/02, 09:21 HALF THE BATTLE Civilian morale in Britain during the Second World War ROBERT MACKAY Manchester University Press Manchester and New York distributed exclusively in the USA by Palgrave Robert Mackay - 9781526137425 Downloaded from manchesterhive.com at 09/24/2021 07:30:30PM via free access prelim.p65 3 16/09/02, 09:21 Copyright © Robert Mackay 2002 The right of Robert Mackay to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Published by Manchester University Press Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9NR, UK and Room 400, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk Distributed exclusively in the USA by Palgrave, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA Distributed exclusively in Canada by UBC Press, University of British Columbia, 2029 West Mall, Vancouver, BC, Canada V6T 1Z2 British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data applied for ISBN 0 7190 5893 7 hardback 0 7190 5894 5 paperback First published 2002 10 09 08 07 06 05 04 03 02 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Typeset by Freelance Publishing Services, Brinscall, Lancs. -

1 "Documentary Films" an Entry in the Encylcopedia of International Media

1 "Documentary Films" An entry in the Encylcopedia of International Media and Communication, published by the Academic Press, San Diego, California, 2003 2 DOCUMENTARY FILMS Jeremy Murray-Brown, Boston University, USA I. Introduction II. Origins of the documentary III. The silent film era IV. The sound film V. The arrival of television VI. Deregulation: the 1980s and 1990s VII. Conclusion: Art and Facts GLOSSARY Camcorders Portable electronic cameras capable of recording video images. Film loop A short length of film running continuously with the action repeated every few seconds. Kinetoscope Box-like machine in which moving images could be viewed by one person at a time through a view-finder. Music track A musical score added to a film and projected synchronously with it. In the first sound films, often lasting for the entire film; later blended more subtly with dialogue and sound effects. Nickelodeon The first movie houses specializing in regular film programs, with an admission charge of five cents. On camera A person filmed standing in front of the camera and often looking and speaking into it. Silent film Film not accompanied by spoken dialogue or sound effects. Music and sound effects could be added live in the theater at each performance of the film. Sound film Film for which sound is recorded synchronously with the picture or added later to give this effect and projected synchronously with the picture. Video Magnetized tape capable of holding electronic images which can be scanned electronically and viewed on a television monitor or projected onto a screen. Work print The first print of a film taken from its original negative used for editing and thus not fit for public screening. -

The Battle of Britain, 1945–1965 : the Air Ministry and the Few / Garry Campion

Copyrighted material – 978–0–230–28454–8 © Garry Campion 2015 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, Saffron House, 6–10 Kirby Street, London EC1N 8TS. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The author has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2015 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN Palgrave Macmillan in the UK is an imprint of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS. Palgrave Macmillan in the US is a division of St Martin’s Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010. Palgrave Macmillan is the global academic imprint of the above companies and has companies and representatives throughout the world. Palgrave® and Macmillan® are registered trademarks in the United States, the United Kingdom, Europe and other countries. ISBN 978–0–230–28454–8 This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. Logging, pulping and manufacturing processes are expected to conform to the environmental regulations of the country of origin. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. -

Guide to Film Movements

This was originally published by Empire ( here is their Best of 2020 list) but no longer available. A Guide to Film Movements . FRENCH IMPRESSIONISM (1918-1930) Key filmmakers: Abel Gance, Louis Delluc, Germaine Dulac, Marcel L'Herbier, Jean Epstein What is it? The French Impressionist filmmakers took their name from their painterly compatriots and applied it to a 1920s boom in silent film that jolted cinema in thrilling new directions. The devastation of World War I parlayed into films that delved into the darker corners of the human psyche and had a good rummage about while they were there. New techniques in non-linear editing, point-of-view storytelling and camera work abounded. Abel Gance’s Napoleon introduced the widescreen camera and even stuck a camera operator on rollerskates to get a shot, while Marcel L'Herbier experimented with stark new lighting styles. Directors like Gance, Germaine Dulac and Jean Epstein found valuable support from Pathé Fréres and Leon Gaumont, France’s main production houses, in a reaction to the stifling influx of American films. As Empire writer and cineguru David Parkinson points out in 100 Ideas That Changed Film, the group’s figurehead, Louis Delluc, was instrumental in the still-new art form being embraced as something apart, artistically and geographically. “French cinema must be cinema,” he stressed. “French cinema must be French.” And being French, it wasn’t afraid to get a little sexy if the circumstances demanded. Germaine Dulac’s The Seashell And The Clergyman, an early step towards surrealism, gets into the head of a lascivious priest gingering after a general’s wife in a way usually frowned on in religious circles. -

Pdf/ Mow/Nomination Forms United Kingdom Battle of the Somme (Accessed 18.04.2014)

Notes Introduction: Critical and Historical Perspectives on British Documentary 1. Forsyth Hardy, ‘The British Documentary Film’, in Michael Balcon, Ernest Lindgren, Forsyth Hardy and Roger Manvell, Twenty Years of British Film 1925–1945 (London, 1947), p.45. 2. Arts Enquiry, The Factual Film: A Survey sponsored by the Dartington Hall Trustees (London, 1947), p.11. 3. Paul Rotha, Documentary Film (London, 4th edn 1968 [1936]), p.97. 4. Roger Manvell, Film (Harmondsworth, rev. edn 1946 [1944]), p.133. 5. Paul Rotha, with Richard Griffith, The Film Till Now: A Survey of World Cinema (London, rev. edn 1967 [1930; 1949]), pp.555–6. 6. Michael Balcon, Michael Balcon presents ...A Lifetime of Films (London, 1969), p.130. 7. André Bazin, What Is Cinema? Volume II, trans. Hugh Gray (Berkeley, 1971), pp.48–9. 8. Ephraim Katz, The Macmillan International Film Encyclopedia (London, 1994), p.374. 9. Kristin Thompson and David Bordwell, Film History: An Introduction (New York, 1994), p.352. 10. John Grierson, ‘First Principles of Documentary’, in Forsyth Hardy (ed.), Grierson on Documentary (London, 1946), pp.79–80. 11. Ibid., p.78. 12. Ibid., p.79. 13. This phrase – sometimes quoted as ‘the creative interpretation of actual- ity’ – is universally credited to Grierson but the source has proved elusive. It is sometimes misquoted with ‘reality’ substituted for ‘actuality’. In the early 1940s, for example, the journal Documentary News Letter, published by Film Centre, which Grierson founded, carried the banner ‘the creative interpretation of reality’. 14. Rudolf Arnheim, Film as Art, trans. L. M. Sieveking and Ian F. D. Morrow (London, 1958 [1932]), p.55. -

British Columbia School Children and the Second World War

"THE WAR WAS A VERY VIVID PART OF MY LIFE": BRITISH COLUMBIA SCHOOL CHILDREN AND THE SECOND WORLD WAR. By EMILIE L. MONTGOMERY B.Ed., The University of British Columbia, 1984 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Centre for the Study of Curriculum and Instruction) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA October 1991 ©Emilie L. Montgomery In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of tducdrar\ CtAvy!r,A luw $ ImW The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada DE-6 (2/88) ABSTRACT This thesis examines the influence of the Second World War on the lives of British,Columbia school children. It employs a variety of primary and secondary sources, including interviews with adults who, during 1939-1945, attended school in British Columbia. War time news and propaganda through such means as newspaper, movies, newsreels and radio broadcasts permeated children's lives. War influenced the whole school curriculum and especially led to changes in Social Studies, Physical Education and Industrial Arts. -

Past and Present 19/7/05 3:53 Pm Page I

2725 M&M Past and Present 19/7/05 3:53 pm Page i Turner Classic Movies British Film Guides General Editor: Jeffrey Richards Brighton Rock Dracula The 39 Steps Steve Chibnall Peter Hutchings Mark Glancy A Hard Day’s Night Get Carter The Dam Busters Stephen Glynn Steve Chibnall John Ramsden My Beautiful The Charge of the Light A Night to Remember Launderette Brigade Jeffrey Richards Christine Geraghty Mark Connelly The Private Life of Whiskey Galore! & The Henry VIII Maggie Greg Walker Colin McArthur Cinema and Society Series General Editor: Jeffrey Richards ‘Banned in the USA’: British Films in the United States and Their Censorship, 1933–1960 Anthony Slide Best of British: Cinema and Society from 1930 to the Present Anthony Aldgate & Jeffrey Richards Brigadoon, Braveheart and the Scots: Distortions of Scotland in Hollywood Cinema Colin McArthur British Cinema and the Cold War Tony Shaw The British at War: Cinema, State and Propaganda, 1939–1945 James Chapman Christmas at the Movies: Images of Christmas in American, British and European Cinema Edited by Mark Connelly The Crowded Prairie: American National Identity in the Hollywood Western Michael Coyne Distorted Images: British National Identity and Film in the 1920s Kenton Bamford An Everyday Magic: Cinema and Cultural Memory Annette Kuhn Film and Community in Britain and France: From La Règle du Jeu to Room at the Top Margaret Butler 2725 M&M Past and Present 19/7/05 3:53 pm Page ii Film Propaganda: Soviet Russia and Nazi Germany Richard Taylor Hollywood Genres and Post-War America: Masculinity, -

“The Sort of Man”

“The sort of man” Politics, Clothing and Characteristics in British Propaganda Depictions of Royal Air Force Aviators, 1939-1945 By Liam Barnsdale A thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Victoria University of Wellington 2019 Abstract Throughout the Second World War, the Royal Air Force saw widespread promotion by Britain’s propagandists. RAF personnel, primarily aviators, and their work made frequent appearances across multiple propaganda media, being utilised for a wide range of purposes from recruitment to entertainment. This thesis investigates the depictions of RAF aviators in British propaganda material produced during the Second World War. The chronological changes these depictions underwent throughout the conflict are analysed and compared to broader strategic and propaganda trends. Additionally, it examines the repeated use of clothing and characteristics as identifying symbols in these representations, alongside their appearances in commercial advertisements, cartoons and personal testimony. Material produced or influenced by the Ministry of Information, Air Ministry and other parties within Britain’s propaganda machine across multiple media are examined using close textual analysis. Through this examination, these parties’ influences on RAF aviators’ propaganda depictions are revealed, and these representations are compared to reality as described by real aviators in post- war accounts. While comparing reality to propaganda, the traits unique to, or excessively promoted in, propaganda are identified, and condensed into a specific set of visual symbols and characteristics used repeatedly in propaganda depictions of RAF aviators. Examples of these traits from across multiple media are identified and analysed, revealing their systematic use as aids for audience recognition and appreciation. -

Pat Jackson's White Corridors

The national health: Pat Jackson’s White Corridors charles barr W C, a hospital drama first shown in June 1951, belongs to the small class of fictional films that deny themselves a musical score. Even the brief passages that top and tail the film, heard over the initial credits and the final image, were added against the wish of its director, Pat Jackson. Jackson had spent the first ten years of his career in documentary, joining the GPO Unit in the mid-1930s and staying on throughout the war after its rebranding as Crown, and the denial of music is clearly part of a strategy for giving a sense of documentary-like reality to the fictional material of White Corridors. There is a certain paradox here, in that actual documentaries, like news- reels, normally slap on music liberally. To take two submarine-centred features, released almost simultaneously in 1943, Gainsborough’s fictional We Dive at Dawn, in which Anthony Asquith directs a cast of familiar pro- fessionals headed by John Mills and Eric Portman, has virtually no music, while Crown’s ‘story-documentary’, Close Quarters, whose cast are all acting out their real-life naval roles, has a full-scale score by Gordon Jacob. Other films in this celebrated wartime genre have even more prominent and powerful scores, by Vaughan Williams for Coastal Command (1942), by William Alwyn for Fires were Started (1943) and by Clifton Parker for Jack- son’s own Western Approaches (1945). One can rationalise this by saying that documentary has enough markers of authenticity already at the level of dramatic and visual construction, and a corresponding need for the bonus of I had the not untypical experience of being taken to a lot of worthy British films by parents and teachers in the 1950s, and then reacting against them when the riches of non-British cinema were opened up, notably by Movie magazine, in the 1960s. -

A Brief History of Raf Mildenhall

A BRIEF HISTORY OF RAF MILDENHALL I am indebted to Mr. H Dring for allowing me to use material from his father’s (Mr. C. Dring) book entitled ‘A History of RAF Mildenhall’ in this account. RAF Mildenhall was established in 1934, however people living in the area had long been accustomed to the sight of aircraft in the skies overhead. The Army had, for many years, made use of the extensive Breckland area to the north east of Mildenhall for its military training. In 1929 it became known locally that Mildenhall had been selected to be the site of the first of the new-style bomber bases. The town was suffering from the effects of the agricultural depression and the local people welcomed the thought of some much needed employment. Work began in earnest in October, 1930 when the first building, a large office for the construction staff, was erected. The Ministry Of Transport laid down concrete access roads and in 1931 a London based building firm took the main contract. The first phase of construction lasted for some 3 years; most of the buildings from this period are still in existence, although now with different uses. The original hangers, Numbers 1 and 5, were designed to such a high specification that they are in use today with the United States Air Force. The first control tower, a small bungalow type building between hangers 2 and 3, has long since disappeared. The airfield when finished had 3 grass runways, the longest being the NE-SW runway at 1300 yards.