British Columbia School Children and the Second World War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Communism and the Portrayal of the Working Class at the National Film Board of Canada, 1939-1946

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2007 Filming politics: communism and the portrayal of the working class at the National Film Board of Canada, 1939-1946 Khouri, Malek University of Calgary Press Khouri, M. "Filming politics: communism and the portrayal of the working class at the National Film Board of Canada, 1939-1946". Series: Cinemas off centre series; 1912-3094: No. 1. University of Calgary Press, Calgary, Alberta, 2007. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/49340 book http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 3.0 Unported Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca University of Calgary Press www.uofcpress.com FILMING POLITICS: COMMUNISM AND THE PORTRAYAL OF THE WORKING CLASS AT THE NATIONAL FILM BOARD OF CANADA, 1939–46 by Malek Khouri ISBN 978-1-55238-670-5 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected] Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specific work without breaching the artist’s copyright. -

Here We Are at 500! the BRL’S 500 to Be Exact and What a Trip It Has Been

el Fans, here we are at 500! The BRL’s 500 to be exact and what a trip it has been. Imagibash 15 was a huge success and the action got so intense that your old pal the Teamster had to get involved. The exclusive coverage of that ppv is in this very issue so I won’t spoil it and give away the ending like how the ship sinks in Titanic. The Johnny B. Cup is down to just four and here are the representatives from each of the IWAR’s promotions; • BRL Final: Sir Gunther Kinderwacht (last year’s winner) • CWL Final: Jane the Vixen Red (BRL, winner of 2017 Unknown Wrestler League) • IWL Final: Nasty Norman Krasner • NWL Final: Ricky Kyle In one semi-final, we will see bitter rivals Kinderwacht and Red face off while in the other the red-hot Ricky Kyle will face the, well, Nasty Normal Krasner. One of these four will win The self-professed “Greatest Tag team wrestler the 4th Johnny B Cup and the results will determine the breakdown of the prizes. ? in the world” debuted in the NWL in 2012 and taunt-filled promos earned him many enemies. The 26th Marano Memorial is also down to the final 5… FIVE? Well since the Suburban Hell His “Teamster Challenge” offered a prize to any Savages: Agent 26 & Punk Rock Mike and Badd Co: Rick Challenger & Rick Riley went to a NWL rookie who could capture a Tag Team title draw, we will have a rematch. The winner will advance to face Sledge and Hammer who won with him, but turned ugly when he kept blaming the CWL bracket. -

CDN Battle of Vimy Ridge.Pdf

Bataille de Vimy-E.qxp 1/2/07 11:37 AM Page 1 Bataille de Vimy-E.qxp 1/2/07 11:37 AM Page 2 Bataille de Vimy-E.qxp 1/2/07 11:37 AM Page 3 BRERETON GREENHOUS STEPHEN J. HARRIS Canada and the BATTLE OF VIMY RIDGE 9-12 April 1917 Bataille de Vimy-E.qxp 1/2/07 11:37 AM Page 4 Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Greenhous, Brereton, 1929- Stephen J. Harris, 1948- Canada and the Battle of Vimy Ridge, 9-12 April 1917 Issued also in French under title: Le Canada et la Bataille de Vimy 9-12 avril 1917. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-660-16883-9 DSS cat. no. D2-90/1992E-1 2nd ed. 2007 1.Vimy Ridge, Battle of, 1917. 2.World War, 1914-1918 — Campaigns — France. 3. Canada. Canadian Army — History — World War, 1914-1918. 4.World War, 1914-1918 — Canada. I. Harris, Stephen John. II. Canada. Dept. of National Defence. Directorate of History. III. Title. IV.Title: Canada and the Battle of Vimy Ridge, 9-12 April 1917. D545.V5G73 1997 940.4’31 C97-980068-4 Cet ouvrage a été publié simultanément en français sous le titre de : Le Canada et la Bataille de Vimy, 9-12 avril 1917 ISBN 0-660-93654-2 Project Coordinator: Serge Bernier Reproduced by Directorate of History and Heritage, National Defence Headquarters Jacket: Drawing by Stéphane Geoffrion from a painting by Kenneth Forbes, 1892-1980 Canadian Artillery in Action Original Design and Production Art Global 384 Laurier Ave.West Montréal, Québec Canada H2V 2K7 Printed and bound in Canada All rights reserved. -

NATIONAL FILM BOARD of CANADA FEATURED at Moma

The Museum off Modern Art 50th Anniversary NO. 16 ID FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE March 3, 1981 DOCUMENTARY FILMS FROM THE NATIONAL FILM BOARD OF CANADA FEATURED AT MoMA NATIONAL FILM BOARD OF CANADA: A RETROSPECTIVE is a three-part tribute presented by The Museum of Modern Art in recog nition of NFBC's 41 years Of exceptional filmmaking. PART TWO: DOCUMENTARY FILMS, running from March 26 through May 12 in the Museum's Roy and Niuta Titus Auditorium, will trace the develop ment of the documentary form at NFBC, and will be highlighted by a selection of some of the finest films directed by Donald Brittain, whose work has won wide acclaim and numerous awards. PART TWO: DOCUMENTARY will get off to an auspicious start with twelve of Donald Brittain's powerful and unconventional portraits of exceptional individuals. Best known in this country for "Volcano: An Inquiry Into The Life and Death of Malcolm Lowry" (1976), Brittain brings his personal stamp of creative interpretation to such subjects as America's love affair with the automobile in "Henry Ford's America" (1976) ; the flamboyant Lord Thompson of Fleet Street (the newspaper baron who just sold the cornerstone of his empire, The London Times) in "Never A Backward Step" (1966); Norman Bethune, the Canadian poet/ doctor/revolutionary who became a great hero in China when he marched with Mao ("Bethune" 1964); and the phenomenal media hysteria sur rounding the famous quintuplets in "The Diorme Years" (1979) . "Memo randum" (1965) accompanies a Jewish glazier from Tcronto when he takes his son back to the concentration camp where he was interned, an emotion al and historical pilgrimage of strong impact and sensitivity. -

Interaction and Perception in Anglo-German Armies: 1689-1815

Interaction and Perception in Anglo-German Armies: 1689-1815 Mark Wishon Ph.D. Thesis, 2011 Department of History University College London Gower Street London 1 I, Mark Wishon confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 2 ABSTRACT Throughout the ‘long eighteenth century’ Britain was heavily reliant upon soldiers from states within the Holy Roman Empire to augment British forces during times of war, especially in the repeated conflicts with Bourbon, Revolutionary, and Napoleonic France. The disparity in populations between these two rival powers, and the British public’s reluctance to maintain a large standing army, made this external source of manpower of crucial importance. Whereas the majority of these forces were acting in the capacity of allies, ‘auxiliary’ forces were hired as well, and from the mid-century onwards, a small but steadily increasing number of German men would serve within British regiments or distinct formations referred to as ‘Foreign Corps’. Employing or allying with these troops would result in these Anglo- German armies operating not only on the European continent but in the American Colonies, Caribbean and within the British Isles as well. Within these multinational coalitions, soldiers would encounter and interact with one another in a variety of professional and informal venues, and many participants recorded their opinions of these foreign ‘brother-soldiers’ in journals, private correspondence, or memoirs. These commentaries are an invaluable source for understanding how individual Briton’s viewed some of their most valued and consistent allies – discussions that are just as insightful as comparisons made with their French enemies. -

Chapter 3 Heroines in a Time of War: Nelvana of the Northern Lights And

Chapter 3 Heroines in a Time of War: Nelvana of the Northern Lights and Wonder Woman as Symbols of the United States and Canada Scores of superheroes emerged in comic books just in time to defend the United States and Canada from the evil machinations of super-villains, Hitler, Mussolini, and other World War II era enemies. By 1941, War Nurse Pat Parker, Miss America, Pat Patriot, and Miss Victory were but a few of the patriotic female characters who had appeared in comics to fight villains and promote the war effort. These characters had all but disappeared by 1946, a testament to their limited wartime relevance. Though Nelvana of the Northern Lights (hereafter “Nelvana”) and Wonder Woman first appeared alongside the others in 1941, they have proven to be more enduring superheroes than their crime-fighting colleagues. In particular, Nelvana was one of five comic book characters depicted in the 1995 Canada Post Comic Book Stamp Collection, and Wonder Woman was one of ten DC Comics superheroes featured in the 2006 United States Postal Service (USPS) Commemorative Stamp Series. The uniquely enduring iconic statuses of Nelvana and Wonder Woman result from their adventures and character development in the context of World War II and the political, social, and cultural climates in their respective English-speaking areas of North America. Through a comparative analysis of Wonder Woman and Nelvana, two of their 1942 adventures, and their subsequent deployment through government-issued postage stamps, I will demonstrate how the two characters embody and reinforce what Michael Billig terms “banal nationalism” in their respective national contexts. -

Canadian Masculinity in the NFB's Second World War Series

Sheridan College SOURCE: Sheridan Scholarly Output, Research, and Creative Excellence Faculty Books School of Communication and Literary Studies 10-2011 Who’s on the Home Front? Canadian Masculinity in the NFB’s Second World War Series “Canada Carries On” Michael Brendan Baker Sheridan College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://source.sheridancollege.ca/fhass_comm_book Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons SOURCE Citation Baker, Michael Brendan, "Who’s on the Home Front? Canadian Masculinity in the NFB’s Second World War Series “Canada Carries On”" (2011). Faculty Books. 1. https://source.sheridancollege.ca/fhass_comm_book/1 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Communication and Literary Studies at SOURCE: Sheridan Scholarly Output, Research, and Creative Excellence. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Books by an authorized administrator of SOURCE: Sheridan Scholarly Output, Research, and Creative Excellence. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ramsay (d)_x 13/06/11 9:18 AM Page 39 CHAPTER 3 Who’s on the Home Front? Canadian Masculinity in the NFB’s Second World War Series “Canada Carries On” MICHAEL BRENDAN BAKER It is widely accepted, and rightfully so, that the prestige of Canada’s docu- mentary tradition is wedded to the success of its Second World War–era film series, Canada Carries On. John Grierson, founding commissioner of the National Film Board of Canada, and Stuart Legg, the executive producer of the series (and a British documentarian who had worked with Grierson at the General Post Office Film Unit during the 1930s), shaped Canada Carries On in such a way that it became the signpost for Canadian documentaries of the war and immediate postwar eras. -

Truth, Justice, and the Canadian Way: the War-Time Comics of Bell Features Publications Ivan Kocmarek Hamilton, Ontario

Truth, Justice, and the Canadian Way: The War-Time Comics of Bell Features Publications Ivan Kocmarek Hamilton, Ontario 148 What might be called the “First Age of Canadian Comics”1 began on a consum- mately Canadian political and historical foundation. Canada had entered the Second World War on September 10, 1939, nine days after Hitler invaded the Sudetenland and a week after England declared war on Germany. Just over a year after this, on December 6, 1940, William Lyon MacKenzie King led parliament in declaring the War Exchange Conservation Act (WECA) as a protectionist measure to bolster the Canadian dollar and the war economy in general. Among the paper products now labeled as restricted imports were pulp magazines and comic books.2 Those precious, four-colour, ten-cent treasure chests of American culture that had widened the eyes of youngsters from Prince Edward to Vancouver Islands immedi- ately disappeared from the corner newsstands. Within three months—indicia dates give March 1941, but these books were probably on the stands by mid-January— Anglo-American Publications in Toronto and Maple Leaf Publications in Vancouver opportunistically filled this vacuum by putting out the first issues of Robin Hood Comics and Better Comics, respectively. Of these two, the latter is widely considered by collectors to be the first true Canadian comic book becauseRobin Hood Comics Vol. 1 No. 1 seems to have been a tabloid-sized collection of reprints of daily strips from the Toronto Telegram written by Ted McCall and drawn by Charles Snelgrove. Still in Toronto, Adrian Dingle and the Kulbach twins combined forces to release the first issue of Triumph-Adventure Comics six months later (August 1941), and then publisher Cyril Bell and his artist employee Edmund T. -

Japanese Reflections on World War II and the American Occupation Japanese Reflections on World War II and the American Occupation Asian History

3 ASIAN HISTORY Porter & Porter and the American Occupation II War World on Reflections Japanese Edgar A. Porter and Ran Ying Porter Japanese Reflections on World War II and the American Occupation Japanese Reflections on World War II and the American Occupation Asian History The aim of the series is to offer a forum for writers of monographs and occasionally anthologies on Asian history. The Asian History series focuses on cultural and historical studies of politics and intellectual ideas and crosscuts the disciplines of history, political science, sociology and cultural studies. Series Editor Hans Hägerdal, Linnaeus University, Sweden Editorial Board Members Roger Greatrex, Lund University Angela Schottenhammer, University of Salzburg Deborah Sutton, Lancaster University David Henley, Leiden University Japanese Reflections on World War II and the American Occupation Edgar A. Porter and Ran Ying Porter Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: 1938 Propaganda poster “Good Friends in Three Countries” celebrating the Anti-Comintern Pact Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout Amsterdam University Press English-language titles are distributed in the US and Canada by the University of Chicago Press. isbn 978 94 6298 259 8 e-isbn 978 90 4853 263 6 doi 10.5117/9789462982598 nur 692 © Edgar A. Porter & Ran Ying Porter / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2017 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. -

MUNDANE INTIMACIES and EVERYDAY VIOLENCE in CONTEMPORARY CANADIAN COMICS by Kaarina Louise Mikalson Submitted in Partial Fulfilm

MUNDANE INTIMACIES AND EVERYDAY VIOLENCE IN CONTEMPORARY CANADIAN COMICS by Kaarina Louise Mikalson Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Dalhousie University Halifax, Nova Scotia April 2020 © Copyright by Kaarina Louise Mikalson, 2020 Table of Contents List of Figures ..................................................................................................................... v Abstract ............................................................................................................................. vii Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................... viii Chapter 1: Introduction ....................................................................................................... 1 Comics in Canada: A Brief History ................................................................................. 7 For Better or For Worse................................................................................................. 17 The Mundane and the Everyday .................................................................................... 24 Chapter outlines ............................................................................................................. 30 Chapter 2: .......................................................................................................................... 37 Mundane Intimacy and Slow Violence: ........................................................................... -

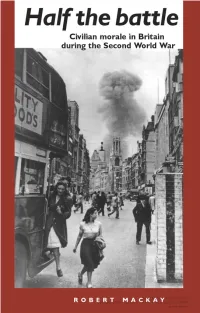

Robert Mackay - 9781526137425 Downloaded from Manchesterhive.Com at 09/24/2021 07:30:30PM Via Free Access HALF the BATTLE

Robert Mackay - 9781526137425 Downloaded from manchesterhive.com at 09/24/2021 07:30:30PM via free access HALF THE BATTLE Robert Mackay - 9781526137425 Downloaded from manchesterhive.com at 09/24/2021 07:30:30PM via free access prelim.p65 1 16/09/02, 09:21 Robert Mackay - 9781526137425 Downloaded from manchesterhive.com at 09/24/2021 07:30:30PM via free access prelim.p65 2 16/09/02, 09:21 HALF THE BATTLE Civilian morale in Britain during the Second World War ROBERT MACKAY Manchester University Press Manchester and New York distributed exclusively in the USA by Palgrave Robert Mackay - 9781526137425 Downloaded from manchesterhive.com at 09/24/2021 07:30:30PM via free access prelim.p65 3 16/09/02, 09:21 Copyright © Robert Mackay 2002 The right of Robert Mackay to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Published by Manchester University Press Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9NR, UK and Room 400, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk Distributed exclusively in the USA by Palgrave, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA Distributed exclusively in Canada by UBC Press, University of British Columbia, 2029 West Mall, Vancouver, BC, Canada V6T 1Z2 British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data applied for ISBN 0 7190 5893 7 hardback 0 7190 5894 5 paperback First published 2002 10 09 08 07 06 05 04 03 02 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Typeset by Freelance Publishing Services, Brinscall, Lancs. -

A City "... Waiting for the Sunrise " : Toronto in Song and Sound*

A City "... Waiting for the Sunrise " : Toronto in Song and Sound* Michael J. Doucet Abstract: One aspect of urban culture is examined to evaluate Toronto's position within the urban hierarchy, namely, the production of songs and sounds about the city. Although much music has been performed and created in Toronto over the years, and many songs have been urritten about a variety of features of life in the city, the musical images of Toronto remain largely unknown beyond its borders—even to many of the city's own residents. If Toronto is a "world-class city," the evidence for such a claim would have to be found on other dimensions than the one explored here. No one ever wrote / A single note / About Toronto. — Johnny Wayne and Frank Shuster (19%) I find that lately, I'm missing old Toronto, Where bass is strong and drums are full of fire. — from the Lenny Breau song "New York City" (1987) No nation can exist by the balance sheet alone. Stories, song, dance, music, art and the rest are the lifeblood of a country, the cultural images defining a people just as surely as their geography and the gross national product. — Robert Lewis, editor of Maclean's (19%) Interestingly, though, we don't seem to have an immediately identifiable style. The last time anyone spoke about a 'Toronto Sound' [former Mayor] Alan Lamport was booting hippies out of Yorkville. Unlike a Nashville or Manchester, there isn't any one thing that makes you say 'That's Toronto' -- Bob Mackowycz, writer and broadcaster (1991) Toronto itself doesn't have a distinctive civic culture.