Defending the Constitution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guide to Alice Marshall Women's History Collection

Guide to the Alice Marshall Women’s History Collection, ca. 1546-1997. The Pennsylvania State University Penn State Harrisburg Library Archives and Special Collections Contact Information: Heidi Abbey Moyer Archivist and Humanities Reference Librarian Coordinator of Archives and Special Collections Penn State Harrisburg Library Archives and Special Collections 351 Olmsted Drive, Room 303 Middletown, PA 17057-4850 Tel.: 717.948.6056 E-mail: [email protected] Web: https://libraries.psu.edu/about/libraries/ penn-state-harrisburg-library/alice-marshall-womens-history-collection Date Completed: August 2010; Last Revised: 25 May 2017 © 2007-2017 The Pennsylvania State University. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Creator: Marshall, Alice Kahler. Title: Alice Marshall Women’s History Collection. Dates: ca. 1546-1997, bulk 1840-1950. Accession No.: AKM 91/1 – AKM 91/95. Language: Bulk of materials in English; some French. Extent: 238 cubic feet. Repository: Archives and Special Collections, Penn State Harrisburg Library, University Libraries, Pennsylvania State University. Administrative Information Access This collection is open for research. There are no access restrictions on this collection. Permission is required to quote from or duplicate materials in this collection. Usage Restrictions Use of audiotapes may require reformatting and/or production of listening copies. Acquisitions Information Gift and purchase of Alice K. Marshall of Camp Hill, Pa., in 1991. Processing Information Processed by: Heidi Abbey Moyer, Archivist and Humanities Reference Librarian and Coordinator of Archives and Special Collections (2006-Present), and Martha Sachs, Former Curator of the Alice Marshall Collection; in collaboration with Katie Barrett, Public Services Assistant (2014-Present), Lynne Calamia, American Studies Graduate Student (2007-2008); Jessica Charlton, Humanities Graduate Student (2008); Danielle K. -

Scottsih Newspapers Have a Long Hisotry Fof Involvement With

68th IFLA Council and General Conference August 18-24, 2002 Code Number: 051-127-E Division Number: V Professional Group: Newspapers RT Joint Meeting with: - Meeting Number: 127 Simultaneous Interpretation: - Scottish Newspapers and Scottish National Identity in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries I.G.C. Hutchison University of Stirling Stirling, UK Abstract: Scotland is distinctive within the United Kingdom newspaper industry both because more people read papers and also because Scots overwhelmingly prefer to read home-produced organs. The London ‘national’ press titles have never managed to penetrate and dominate in Scotland to the preponderant extent that they have achieved in provincial England and Wales. This is true both of the market for daily and for Sunday papers. There is also a flourishing Scottish local weekly sector, with proportionately more titles than in England and a very healthy circulation total. Some of the reasons for this difference may be ascribed to the higher levels of education obtaining in Scotland. But the more influential factor is that Scotland has retained distinctive institutions, despite being part of Great Britain for almost exactly three hundred years. The state church, the education system and the law have not been assimilated to any significant amount with their counterparts south of the border. In the nineteenth century in particular, religious disputes in Scotland generated a huge amount of interest. Sport in Scotlaand, too, is emphatically not the same as in England, whether in terms of organisation or in relative popularity. Additionally, the menu of major political issues in Scotland often has been and is quite divergent from England – for instance, the land question and self-government. -

Minority Percentages at Participating Newspapers

Minority Percentages at Participating Newspapers Asian Native Asian Native Am. Black Hisp Am. Total Am. Black Hisp Am. Total ALABAMA The Anniston Star........................................................3.0 3.0 0.0 0.0 6.1 Free Lance, Hollister ...................................................0.0 0.0 12.5 0.0 12.5 The News-Courier, Athens...........................................0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Lake County Record-Bee, Lakeport...............................0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 The Birmingham News................................................0.7 16.7 0.7 0.0 18.1 The Lompoc Record..................................................20.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 20.0 The Decatur Daily........................................................0.0 8.6 0.0 0.0 8.6 Press-Telegram, Long Beach .......................................7.0 4.2 16.9 0.0 28.2 Dothan Eagle..............................................................0.0 4.3 0.0 0.0 4.3 Los Angeles Times......................................................8.5 3.4 6.4 0.2 18.6 Enterprise Ledger........................................................0.0 20.0 0.0 0.0 20.0 Madera Tribune...........................................................0.0 0.0 37.5 0.0 37.5 TimesDaily, Florence...................................................0.0 3.4 0.0 0.0 3.4 Appeal-Democrat, Marysville.......................................4.2 0.0 8.3 0.0 12.5 The Gadsden Times.....................................................0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Merced Sun-Star.........................................................5.0 -

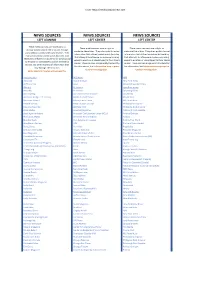

Left Media Bias List

From -https://mediabiasfactcheck.com NEWS SOURCES NEWS SOURCES NEWS SOURCES LEFT LEANING LEFT CENTER LEFT CENTER These media sources are moderately to These media sources have a slight to These media sources have a slight to strongly biased toward liberal causes through moderate liberal bias. They often publish factual moderate liberal bias. They often publish factual story selection and/or political affiliation. They information that utilizes loaded words (wording information that utilizes loaded words (wording may utilize strong loaded words (wording that that attempts to influence an audience by using that attempts to influence an audience by using attempts to influence an audience by using appeal appeal to emotion or stereotypes) to favor liberal appeal to emotion or stereotypes) to favor liberal to emotion or stereotypes), publish misleading causes. These sources are generally trustworthy causes. These sources are generally trustworthy reports and omit reporting of information that for information, but Information may require for information, but Information may require may damage liberal causes. further investigation. further investigation. Some sources may be untrustworthy. Addicting Info ABC News NPR Advocate Above the Law New York Times All That’s Fab Aeon Oil and Water Don’t Mix Alternet Al Jazeera openDemocracy Amandla Al Monitor Opposing Views AmericaBlog Alan Guttmacher Institute Ozy Media American Bridge 21st Century Alaska Dispatch News PanAm Post American News X Albany Times-Union PBS News Hour Backed by Fact Akron Beacon -

Villages Daily Sun Inks Press, Postpress Deals for New Production

www.newsandtech.com www.newsandtech.com September/October 2019 The premier resource for insight, analysis and technology integration in newspaper and hybrid operations and production. Villages Daily Sun inks press, postpress deals for new production facility u BY TARA MCMEEKIN CONTRIBUTING WRITER The Villages (Florida) Daily Sun is on the list of publishers which is nearer to Orlando. But with development trending as winning the good fight when it comes to community news- it is, Sprung said The Daily Sun will soon be at the center of the papering. The paper’s circulation is just over 60,000, and KBA Photo: expanded community. — thanks to rapid growth in the community — that number is steadily climbing. Some 120,000 people already call The Partnerships key Villages home, and approximately 300 new houses are being Choosing vendors to supply various parts of the workflow at built there every month. the new facility has been about forming partnerships, accord- To keep pace with the growth, The Daily Sun purchased a Pictured following the contract ing to Sprung. Cost is obviously a consideration, but success brand-new 100,000-square-foot production facility and new signing for a new KBA press in ultimately depends on relationships, he said — both with the Florida: Jim Sprung, associate printing equipment. The publisher is confident the investment publisher for The Villages Media community The Daily Sun serves and the technology providers will help further entrench The Daily Sun as the definitive news- Group; Winfried Schenker, senior who help to produce the printed product. paper publisher and printer in the region. -

The Old New Journalism?

ORBIT-OnlineRepository ofBirkbeckInstitutionalTheses Enabling Open Access to Birkbeck’s Research Degree output The development and impact of campaigning journal- ism in Britain, 1840-1875 : the old new journalism? https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/40128/ Version: Full Version Citation: Score, Melissa Jean (2015) The development and impact of campaigning journalism in Britain, 1840-1875 : the old new journalism? [Thesis] (Unpublished) c 2020 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copy- right law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit Guide Contact: email Birkbeck, University of London The Development and Impact of Campaigning Journalism in Britain, 1840–1875: The Old New Journalism? Melissa Jean Score Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy November 2014 2 Declaration I, Melissa Jean Score, declare that this thesis is all my own work. Signed declaration_________________________________________ Date_____________________ 3 Abstract This thesis examines the development of campaigning writing in newspapers and periodicals between 1840 and 1875 and its relationship to concepts of Old and New Journalism. Campaigning is often regarded as characteristic of the New Journalism of the fin de siècle, particularly in the form associated with W. T. Stead at the Pall Mall Gazette in the 1880s. New Journalism was persuasive, opinionated, and sensational. It displayed characteristics of the American mass-circulation press, including eye-catching headlines on newspaper front pages. The period covered by this thesis begins in 1840, with the Chartist Northern Star as the hub of a campaign on behalf of the leaders of the Newport rising of November 1839. -

From Valmy to Waterloo: France at War, 1792–1815

Copyright material from www.palgraveconnect.com - licensed to Universitetsbiblioteket i Tromsoe - PalgraveConnect - 2011-03-08 - PalgraveConnect Tromsoe i - licensed to Universitetsbiblioteket www.palgraveconnect.com material from Copyright 10.1057/9780230294981 - From Valmy to Waterloo, Marie-Cecile Thoral War, Culture and Society, 1750–1850 Series Editors: Rafe Blaufarb (Tallahassee, USA), Alan Forrest (York, UK), and Karen Hagemann (Chapel Hill, USA) Editorial Board: Michael Broers (Oxford, UK), Christopher Bayly (Cambridge, UK), Richard Bessel (York, UK), Sarah Chambers (Minneapolis, USA), Laurent Dubois (Durham, USA), Etienne François (Berlin, Germany), Janet Hartley (London, UK), Wayne Lee (Chapel Hill, USA), Jane Rendall (York, UK), Reinhard Stauber (Klagenfurt, Austria) Titles include: Richard Bessel, Nicholas Guyatt and Jane Rendall (editors) WAR, EMPIRE AND SLAVERY, 1770–1830 Alan Forrest and Peter H. Wilson (editors) THE BEE AND THE EAGLE Napoleonic France and the End of the Holy Roman Empire, 1806 Alan Forrest, Karen Hagemann and Jane Rendall (editors) SOLDIERS, CITIZENS AND CIVILIANS Experiences and Perceptions of the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, 1790–1820 Karen Hagemann, Gisela Mettele and Jane Rendall (editors) GENDER, WAR AND POLITICS Transatlantic Perspectives, 1755–1830 Marie-Cécile Thoral FROM VALMY TO WATERLOO France at War, 1792–1815 Forthcoming: Michael Broers, Agustin Guimera and Peter Hick (editors) THE NAPOLEONIC EMPIRE AND THE NEW EUROPEAN POLITICAL CULTURE Alan Forrest, Etienne François and Karen Hagemann -

James Perry and the Morning Chronicle 179O—I821

I JAMES PERRY AND THE MORNING CHRONICLE- 179O—I821 By l yon Asquith Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of London 1973 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract 3 Preface 5 1. 1790-1794 6 2. 1795-1 805 75 3. 1806-1812 (i) ThB Ministry of the Talents 184 (ii) Reform, Radicalism and the War 1808-12 210 (iii) The Whigs arid the Morning Chronicle 269 4. Perry's Advertising Policy 314 Appendix A: Costs of Production 363 Appendix B: Advertising Profits 365 Appendix C: Government Advertisements 367 5. 1813-1821 368 Conclusion 459 Bibliography 467 3 A BSTRACT This thesis is a study of the career of James Perry, editor and proprietor of the Morning Chronicle, from 1790-1821. Based on an examination of the correspondence of whig and radical polit- icians, and of the files of the morning Chronicle, it illustrates the impact which Perry made on the world of politics and journalism. The main questions discussed are how Perry responded, as a Foxite journalist, to the chief political issues of the day; the extent to which the whigs attempted to influence his editorial policy and the degree to which he reconciled his independence with obedience to their wishes4 the difficulties he encountered as the spokesman of an often divided party; his considerable involvement, which was remarkable for a journalist, in party activity and in the social life of whig politicians; and his success as a newspaper proprietor concerned not only with political propaganda, but with conducting a paper which was distinguished for the quality of its miscellaneous features and for its profitability as a business enterprise. -

5Th Grade Big Idea Study Guides

5th Grade Big Idea Study Guides B ig Ideas 1 & 2 Study Guide: Nature of Science Types of Scientific Investigations: Type of Investigation Description Model a representation of an idea, an object, a process, or a system that is used to describe and explain something that cannot be experienced directly. Simulation an imitation of the functioning of a system or process Systematic Observations documenting descriptive details of events in nature –amounts, sizes, colors, smell, behavior, texture - for example - eclipse observations Field Studies studying plants and animals in their natural habitat Controlled Experiment an investigation in which scientists control variables and set up a test to answer a question. A controlled experiment must always have a control group (used as a comparison group) and a test group. ALL types of Scientific Investigation include making observations and collecting evidence. Observations: ALL scientists make observations. An observation is information about the natural world that is gathered through one of the five senses. An observation is something you see, hear, taste, touch, or smell. List 5 Examples of Observations 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Evidence Evidence is information gathered when scientists make systematic observations or set up an experiment to collect and record data. The data recorded is then analyzed by the scientists in order to base conclusions on the evidence collected. The collection of evidence is a critical part of a scientific investigation. Although the scientific method does not always follow a rigidly defined set of steps, a scientific investigation is only valid if it is based on observations and evidence. Controlled Experiments A controlled experiment is different than all other types of scientific investigations because in an experiment, variables are being controlled by the scientist in order to answer a question. -

ECL Style Guide August ‘07

1 ECL Style Guide August ‘07 Eighteenth-Century Life first adheres to the rules in this style guide. For issues not covered in the style guide, refer to the fifteenth edition of The Chicago Manual of Style (hereinafter, CMS17) for guidance. This is available online at https://www.chicagomanualofstyle.org/home.html Eighteenth-Century Life prefers to receive submissions by e-mail, either in Microsoft Word or in WordPerfect. If that is not possible, sending in 3 ½” disks is preferable to submitting mss. If mss. are submitted, please send three copies. ABBREVIATIONS Corporate, municipal, national, and supranational abbreviations and acronyms appear in full caps. Most initialisms (abbreviations pronounced as strings of letters) are preceded by the. Latin abbreviations, such as e.g. and i.e., are usually restricted to parenthetical text and set in Roman type, not italics, except for sic, which is italicized for visibility’s sake. Pace, Latin for “contrary to,” is italicized to avoid confusion with “pace.” We’ll allow e.g. and i.e. to appear in the text of the notes. According to Chicago Manual, if used in running text, abbreviations should be confined to parenthetical expressions. Personal initials have periods and are spaced. W. E. B. DuBois; C. D. Wright BYLINE AND AFFILIATION The author’s name and affiliation appear on the opening page of each article. No abbreviations are used within the affiliation. If more than one author appears, an ampersand separates the authors. James Smith University of Arizona John Abrams University of Florida & Maureen O’Brien University of Virginia AMPERSANDS The use of ampersands is limited to “The College of William & Mary” on the cover, on the title page, and in copyright slugs, and to separating multiple authors in the byline on article-opening pages. -

Copyright at Common Law in 1774

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OpenCommons at University of Connecticut University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Connecticut Law Review School of Law 2014 Copyright at Common Law in 1774 H. Tomas Gomez-Arostegui Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/law_review Recommended Citation Gomez-Arostegui, H. Tomas, "Copyright at Common Law in 1774" (2014). Connecticut Law Review. 263. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/law_review/263 CONNECTICUT LAW REVIEW VOLUME 47 NOVEMBER 2014 NUMBER 1 Article Copyright at Common Law in 1774 H. TOMÁS GÓMEZ-AROSTEGUI As we approach Congress’s upcoming reexamination of copyright law, participants are amassing ammunition for the battle to come over the proper scope of copyright. One item that both sides have turned to is the original purpose of copyright, as reflected in a pair of cases decided in Great Britain in the late 18th century—the birthplace of Anglo-American copyright. The salient issue is whether copyright was a natural or customary right, protected at common law, or a privilege created solely by statute. These differing viewpoints set the default basis of the right. Whereas the former suggests the principal purpose was to protect authors, the latter indicates that copyright should principally benefit the public. The orthodox reading of these two cases is that copyright existed as a common-law right inherent in authors. In recent years, however, revisionist work has challenged that reading. Relying in part on the discrepancies of 18th-century law reporting, scholars have argued that the natural-rights and customary views were rejected. -

Newspapersinmicroform.Pdf (4.978Mb)

------~~--------~-- - 1 UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO LIBRARY REFERENCE DESK Newspapers in microform fourth edition Z co~piled by 1994 6945 Iqbal Wagle U57 1994 se REF DESK ------- ~--------------- 11 11 11 11 11 11· NEWSPAPERS IN MICROFORM\ III ! : 11 - 11 ~ • Microtext Library • University of Toronto Toronto, Canada 1994 • • • •I' j 11 Introduction 11 It This is a revised list ofnewspapers in microform available in the Microtext Library and the Chen Yu Tung East Asian Library in the John P. Robarts Research Library. The titles are arranged alphabetically by country, then by province or state (if applicable) and by city. Two major collections of particular significance to this guide are 11 Early English Newspapers and Newspapers from the Russian Revolution Era. Unlike the majority of newspapers 11 listed here, none of the titles in either set can be accessed through the University of Toronto's online catalogue. Early English Newspapers is a collection of seventeenth and eighteenth century periodical literature. It 11 includes the British Library's Burney Collection of Early English Newspapers as well as the holdings of Oxford University's BodVean Library. Missing issues from these two collections, and some additional titles are supplied 11 from other important collections, such as the Yale University Library. The collection is an important source for contemporary history, literature, drama, and philosophy. In addition to newspapers, it includes broadsides, periodicals, and Charles Burney's manuscripts. Newspapers from the Russian Revolutionary Era is principally based on the holdings at Columbia University's Herbert Lehman Library. This collection covers almost every facet of the Revolution, and includes papers relating to the Revolution which were printed in other countries.