University Microfilms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Covid-19 Resources for Franklin County Residents

Updated March 31st, 2020 COVID-19 RESOURCES FOR FRANKLIN COUNTY RESIDENTS SOUP KITCHENS Central Community House Broad Street United Methodist Church – Manna Café Location: 1150 E. Main St., Col, OH 43205 Location: 501 E. Broad St., Columbus, OH 43215 Phone: 614-252-3157 Phone: 614-221-4571 EXT: 101 Service Description: Free meal to go. Public transportation accessible Eligibility: All Franklin County Residents Service Description: Offers boxed meals to-go. No Hours: Wednesday at 6 PM; last Wednesday of the building access. month. Eligibility: Anyone Intake Process: Walk-in Hours: Tuesday and Wednesday at 5 PM. Documents: No documents required. Documents: No documents required Columbus Relief Bethany Presbyterian Church Location: 100 Highview Blvd., Col, OH 43207 Location: 206 N. Garfield, Col, OH 43203 Phone: 614-517-2038 Phone: 614-253-0077 Service Description: Free meal to go on Saturdays Service Description: Bethany provides and serves from 11 AM to 2 PM. food to those individuals who need physical Eligibility: All Franklin County Residents nourishment. Hours: Saturday Eligibility: Anyone Intake Process: Walk-in Hours: Saturdays 11:30 a.m.-1:30 p.m. Documents: No documents required. Intake Process: Walk-in Documents: No documents required. Faith Mission Location: 245 N Grant Ave, Columbus, OH 43215 Bishop Griffin Resource Center Phone: (614) 224-6617 Location: 2875 E. Livingston Ave., Col, OH 43209 Service Description: Community Resources and meals Phone: 614-338-8220 are ONLY being provided to current residents, Service Description: Offering and emergency supply of UNLESS in extreme situations. food – approximately 25 shelf stable items, plus meat, Eligibility: eggs and produce, to families that live in our zip Hours: PLEASE CALL TO MAKE AN APPOINTMENT! codes. -

New Albany Teams

2013 New Albany Fred Klink Memorial Basketball Classic 3rd Grade Pool A Pool B Pool C 1. East Side Tigers 4. Dublin Irish 7. Orange 2. Eagles 5. Ohio Bulldogs 8. Upper Arlington 3. WABA Elite 6. Thunder 9. Lancaster 4th Grade Pool D Pool E Pool F 11. Hilliard Huskers 14. Liberty Patriots 17. Worthington Elite 12. New Albany Eagles 15. Dublin Celtics 18. Olentangy Braves 13. Liberty Blue 16. Orange Pioneers 19. USA Hydro 5th Grade Pool G Pool H Pool I Pool J 21. OCC 24. Liberty-Black 27. Olentangy Gunners 30. Ohio Legacy Sharks 22. Liberty-Blue 25. Fairfield Union Falcons 28. Warriors 31. New Albany Eagles 23. Perrysburg-Black 26. Perrysburg-White 29. Lancaster 32. Southwest Storm 33. Ohio Bulldogs 6th Grade Pool K Pool L Pool M 41. New Albany-Gold 44. Hoop Heros 47. Lancaster Gale Force 42. Ohio Hoopsters Hustle 45. Ohio Varsity 48. MVL Warriors 43. Columbus Eagles 46. Licking Co. All Stars 49. Olentangy Showtime Pool N Pool O Pool P 50. Team Legacy Greyhounds 53. Ohio Elite-Gillium 56. Upper Arlington 51. Olentangy Liberty Patriots 54. Ohio Legacy Sports 57. NC Bullets 52. Ohio Havoc 55. Dublin Rocks 58. LC Elite 7th Grade Pool Q Pool R Pool S 61. Eagles 64. SBI Spurs 67. Ohio Elite 62. Eastside Storm 65. Grove City Hounds 68. Ohio Stampede 63. Cap. City Force 66. Muskingum Elite 69. Excel Pool T Pool U Pool V 70. Dublin Dynasty 73. COBA Knights 76. Olentangy Hoopsters 71. Downtowners 74. Energy 77. Cent. Ohio Ravens 72. -

New Albany Teams

2014 Ohio Youth Basketball . Com Classic March 14 - 15 - 16 3rd Grade Boys Pool A Pool B 1. Upeard Thunder 5. Excel 2. New Albany Eagles 6. Olentangy Liberty Patriots 3. Mansfield Cavs 7. Maysville Panthers 4. Cohen Elite Warriors 4th Grade Boys Pool C Pool D Pool E Pool F 11, Worthington Elite 15. Graham 19. Orange Pioneers 22. Liberty Blue 12. Dublin Celtics 16. Team Ohio 20. Dublin Rocks 23. Mansfield Cavs 13. Upper Arlington 17. Dutchtown Dawgs 21. Rat Pack 24. Sandusky Ballers 14. Hilliard Wildcats 18. Sylvania Timberwolves 5th Grade Boys Pool G Pool H 31. All Ohio Buckeyes 35. Ohio Clippers 32. Olentangy Braves 36. Cincy Bombers 33. Mansfield Cavs 37. All Ohio Black 34. Kinnikinnick Kwik 38. Warriors 6th Grade Boys Pool I Pool J Pool K Pool L 41. UA Bears 45. Mid Ohio Pumas Silver 48. Olentangy Stix 51. Cincy Slam 42. Columbus Cavs 46. OLS Sharks 49. Shelby Swish 52. Mid Ohio Fusion 43. Central Ohio Gold 47. Mansfield Cavs White 50. Mansfield Cavs Black 53. Olentangy Thunder 44. Dublin Starz 7th Grade Boys Pool M Pool N Pool O 61. Hoop Heroes Purple 65. COBA Knights 68. Northwest Warriors 62. Positive Creations 66. Hoop Squad 69. XF Tribe 63. C B C 67. Mansfield Lil Tygers 70. Dayton Metro Ank 64. Ohio Slammers Pool P Pool Q 71. Black Swamp Basketball 74. Mansfield Cavs 72. Hoop Heroes Green 75. Toledo Ice 73. Hoop Guru 76. Midwest Heat Dublin Scioto HS * Dublin Coffman HS * Marysville HS 2014 Ohio Youth Basketball . Com Classic March 14 - 15 - 16 8th Grade Boys Pool R Pool S Pool T 81. -

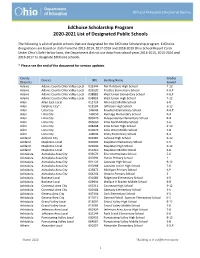

Edchoice Scholarship Program 2020-2021 List of Designated Public Schools

Office of Nonpublic Educational Options EdChoice Scholarship Program 2020-2021 List of Designated Public Schools The following is a list of public schools that are designated for the EdChoice Scholarship program. EdChoice designations are based on data from the 2013-2014, 2017-2018 and 2018-2019 Ohio School Report Cards. Under Ohio’s Safe Harbor laws, the Department did not use data from school years 2014-2015, 2015-2016 and 2016-2017 to designate EdChoice schools. * Please see the end of the document for version updates. County Grades District IRN Building Name (District) Served Adams Adams County Ohio Valley Local 033944 North Adams High School 7-12 Adams Adams County Ohio Valley Local 029520 Peebles Elementary School K-6,P Adams Adams County Ohio Valley Local 038885 West Union Elementary School K-6,P Adams Adams County Ohio Valley Local 038893 West Union High School 7-12 Allen Allen East Local 015724 Allen East Middle School 6-8 Allen Delphos City* 018184 Jefferson High School 9-12 Allen Lima City 146043 Freedom Elementary School K-4,P Allen Lima City 146050 Heritage Elementary School K-4 Allen Lima City 000470 Independence Elementary School K-4 Allen Lima City 005660 Lima North Middle School 5-6 Allen Lima City 008298 Lima Senior High School 9-12 Allen Lima City 040576 Lima West Middle School 7-8 Allen Lima City 146035 Unity Elementary School K-4 Ashland Ashland City 001081 Ashland High School 9-12 Ashland Mapleton Local 000400 Mapleton Elementary School K-5 Ashland Mapleton Local 022640 Mapleton High School 9-12 Ashland Mapleton -

2019-20 Handbook

2019-20 Handbook for Member Schools Grades 7 to 12 OHIO HIGH SCHOOL ATHLETIC ASSOCIATION 4080 Roselea Place, Columbus, OH 43214 (614) 267-2502; Fax: (614) 267-1677; www.ohsaa.org Hours: Monday – Friday, 7:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. OHSAA Mission Statement To serve our member schools and enrich interscholastic opportunities for students. The OHSAA Believes That . • Participation in interscholastic athletics programs is a privilege, not a right. • Participation in interscholastic athletics programs complements a student’s school experience and teaches lifelong lessons of hard work, teamwork and self-discipline. • Participation in interscholastic athletics programs promotes citizenship and sporting behavior, instills a sense of community and promotes a lifetime appreciation for sports and healthy lifestyles. • All students, regardless of ethnicity, race or gender, should have an equal opportunity to participate in interscholastic athletics programs. • Sporting and ethical behavior are expectations in interscholastic athletics by all participants, coaches, administrators, officials and spectators. • Coaches, administrators and contest officials should serve as positive role models who are critical to a student’s development and success. • In order to minimize health and safety risks and maintain ethical standards, it is mandatory that interscholastic athletics participants are free from use of anabolic steroids or other performance-enhancing drugs. • All rules, regulations and facilities for and supervision of interscholastic athletics programs should ensure maximum protection of the health, safety and well-being of each participant. • Limitations should be placed upon the length of sport seasons and the number of interscholastic contests played by participants. • Students should engage in a well-rounded experience that encourages participation in a multitude of extracurricular activities. -

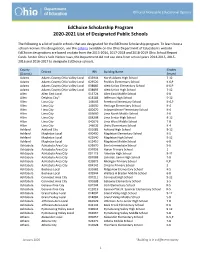

Edchoice Scholarship Program 2021-2022 List of Designated Public Schools

Office of Nonpublic Educational Options EdChoice Scholarship Program 2021-2022 List of Designated Public Schools The following is a list of public schools that are designated for the EdChoice Scholarship program. Schools are designated if they: 1.) are ranked in the lowest 20% in the Performance Index Rankings for both the 2017-2018 and 2018- 2019 school years; and 2.) are operated by a school district for which the average Title 1 formula percentage is 20% or above across the last three school years (2018-2019, 2019-2020, and 2020-2021 school years). School buildings are also designated it they are operated by a school district that has an Academic Distress Commission in place. County District IRN Building Name Grades (District) Served Adams Adams County Ohio Valley Local 038893 West Union High School 7-12 Allen Lima City 005660 Lima North Middle School 5-6 Allen Lima City 008298 Lima Senior High School 9-12 Allen Lima City 040576 Lima West Middle School 7-8 Allen Lima City 146035 Unity Elementary School K-4,P Ashtabula Ashtabula Area City 033670 Erie Intermediate School 5-6 Ashtabula Ashtabula Area City 001123 Lakeside High School 9-12 Ashtabula Ashtabula Area City 007088 Lakeside Junior High School 7-8 Ashtabula Conneaut Area City 007211 Conneaut High School 9-12 Ashtabula Pymatuning Valley Local 030932 Pymatuning Valley High School 9-12 Athens Athens City 037028 The Plains Elementary School K-6 Athens Federal Hocking Local 000620 Amesville Elementary School K-6,P Athens Federal Hocking Local 011478 Federal Hocking High School 9-12 -

Edchoice Scholarship Program 2020-2021 List of Designated Public Schools

Office of Nonpublic Educational Options EdChoice Scholarship Program 2020-2021 List of Designated Public Schools The following is a list of public schools that are designated for the EdChoice Scholarship program. To learn how a school receives this designation, see the criteria available on the Ohio Department of Education’s website. EdChoice designations are based on data from the 2013-2014, 2017-2018 and 2018-2019 Ohio School Report Cards. Under Ohio’s Safe Harbor laws, the Department did not use data from school years 2014-2015, 2015- 2016 and 2016-2017 to designate EdChoice schools. County Grades District IRN Building Name (District) Served Adams Adams County Ohio Valley Local 033944 North Adams High School 7-12 Adams Adams County Ohio Valley Local 029520 Peebles Elementary School K-6,P Adams Adams County Ohio Valley Local 038885 West Union Elementary School K-6,P Adams Adams County Ohio Valley Local 038893 West Union High School 7-12 Allen Allen East Local 015724 Allen East Middle School 6-8 Allen Delphos City* 018184 Jefferson High School 9-12 Allen Lima City 146043 Freedom Elementary School K-4,P Allen Lima City 146050 Heritage Elementary School K-4 Allen Lima City 000470 Independence Elementary School K-4 Allen Lima City 005660 Lima North Middle School 5-6 Allen Lima City 008298 Lima Senior High School 9-12 Allen Lima City 040576 Lima West Middle School 7-8 Allen Lima City 146035 Unity Elementary School K-4 Ashland Ashland City 001081 Ashland High School 9-12 Ashland Mapleton Local 000400 Mapleton Elementary School K-5 Ashland -

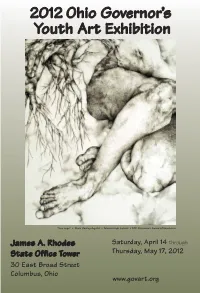

2012 Catalog.Pdf

2012 Ohio Governor’s SPONSORS Youth Art Exhibition SPONSORS: AMACO/brent Art Academy of Cincinnati Art Institute of Pittsburgh Ashland University Blizzard Internet Marketing, Inc. Bowling Green State University, School of Art Capital University - Columbus Ceramics Monthly Cleveland Institute of Art College for Creative Studies - Detroit College of Mount St. Joseph - Cincinnati Columbus Clay Company Columbus College of Art & Design Kansas City Art Institute - Missouri Kendall College of Art & Design of Ferris State University - Grand Rapids, MI Maryland Institute, College of Art - Baltimore Massachusetts College of Art and Design - Boston Montserrat College of Art - Beverly, MA Moore College of Art and Design - Philadelphia New Hampshire Institute of Art - Manchester Ohio Art Education Association Ohio Designer Craftsmen Ohio Northern University - Ada The Ohio State University, College of the Arts Ohio University, School of Art - Athens Otterbein University - Westerville, OH Pittsburgh Technical Institute Pottery Making Illustrated Ringling College of Art and Design - Sarasota, FL School of Advertising Art - Kettering, OH School of the Art Institute of Chicago School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston School of Visual Arts - New York The University of the Arts - Philadelphia The University of Cincinnati, School of Art The University of Dayton The University of Mount Union - Alliance, OH The University of Rio Grande The University of Saint Francis - Fort Wayne, IN Ursuline College - Pepper Pike, OH “Tree Legs” • Devin Owsley-Aquilia • Mason High School • 2011 Governor’s Award of Excellence Utrecht Art Supplies Watkins College of Art, Design and Film - Nashville The Governor of the State of Ohio James A. Rhodes Saturday, April 14 through The Ohio Department of Education Thursday, May 17, 2012 Photography - Monika Kaleps State Office Tower Printing - DC AlphaGraphics 30 East Broad Street Stephanie Rond’s Columbus, Ohio 2012 Top 25 Award of Excellence www.govart.org The 2012 Ohio Governor’s Youth Art Exhibition April 14 through May 17, 2012 The James A. -

Athletic Handbook

South-Western City School District Athletic Handbook Revised: 08/10/18, 3:17 p.m. This page left blank intentionally. Board of Education 2019 Mindy Garverick President Robert W. Ragland, Sr. Vice President Lee Schreiner Member Cathy Johnson Member David Donofrio Member Administrative Staff William Wise, Ph.D. Superintendent Hugh Garside, Jr. Treasurer David Stewart Deputy Superintendent Bradford Faust Assistant Superintendent of Curriculum Erik Shuey, Ed. D. Executive Director of High Schools and Athletics Cheryl Spain, Ed. D. Executive Director of Middle Grades and Testing Jon Marshall Central Crossing High School Dennis Dew Tim Donahue Franklin Heights High School Kyle Gibson Kris Sander Grove City High School Greg Waits Jason Weese Westland High School John Mike George Holly Carr Brookpark Middle School Chad Clark Lori Balough Finland Middle School Jason Phillips Dan Boland Jackson Middle School Brittany Budimirovic Tresa Davis Norton Middle School Sam Belk Brett Harmon Pleasant View Middle School Elizabeth Ketcham Table of Contents Forward .............................................................................................................................................................................. 1 Philosophy ........................................................................................................................................................................ 1 SWCSD and O.C.C. Sportsmanship Statement ............................................................................................................. -

CCP Advisors by School

School CCP Advisor Email ACADEMY FOR URBAN SCHOLARS Diane Jones [email protected] ALTERNATIVE EDUCATION ACADEMY Diane Jones [email protected] AMANDA-CLEARCREEK HIGH SCHOOL Andrea Bennett [email protected] ARTS COLLEGE PREPARATORY ACADEMY Diane Jones [email protected] BEECHCROFT HIGH SCHOOL Nicole Martin [email protected] BELLEFONTAINE HIGH SCHOOL Jordan Falb [email protected] BENJAMIN LOGAN HIGH SCHOOL Jordan Falb [email protected] BERNE UNION HIGH SCHOOL Andrea Bennett [email protected] BEXLEY HIGH SCHOOL Diane Jones [email protected] BIG WALNUT HIGH SCHOOL Andrea Bennett [email protected] BISHOP HARTLEY HIGH SCHOOL Diane Jones [email protected] BISHOP READY HIGH SCHOOL Michelle Miller-Owens [email protected] BISHOP ROSECRANS HIGH SCHOOL Andrea Bennett [email protected] BISHOP WATTERSON HIGH SCHOOL Jordan Falb [email protected] BLOOM-CARROLL HIGH SCHOOL Diane Jones [email protected] BRIGGS SENIOR HIGH SCHOOL Nicole Martin [email protected] BROOKPARK MIDDLE SCHOOL (SWCSD) Nicole Martin [email protected] BROOKWOOD ACADEMY Diane Jones [email protected] BUCKEYE ONLINE SCHOOL FOR SUCCESS Andrea Bennett [email protected] BUCKEYE VALLEY HIGH SCHOOL Jordan Falb [email protected] C-TEC CAREER CENTER Andrea Bennett [email protected] CANAL WINCHESTER HIGH SCHOOL Michelle Miller-Owens [email protected] CENTENNIAL HIGH SCHOOL Nicole Martin [email protected] CENTERBURG HIGH SCHOOL Michelle Miller-Owens [email protected] CENTRAL HIGH SCHOOL Michelle Miller-Owens [email protected] CHARLES SCHOOL AT OHIO DOMINICAN UNIVERSITY Simonne Gage [email protected] CHRISTIFIDELES -

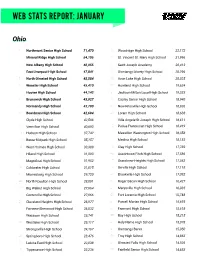

Web Stats Report: January

WEB STATS REPORT: JANUARY Ohio 1 Northmont Senior High School 71,470 31 Woodridge High School 22,172 2 Mineral Ridge High School 54,105 32 St. Vincent-St. Mary High School 21,996 3 New Albany High School 48,955 33 Saint Joseph Academy 20,413 4 East Liverpool High School 47,841 34 Olentangy Liberty High School 20,296 5 North Olmsted High School 45,584 35 Avon Lake High School 20,025 6 Wooster High School 45,410 36 Howland High School 19,634 7 Hoover High School 44,142 37 Jackson-Milton Local High School 19,333 8 Brunswick High School 43,927 38 Copley Senior High School 18,940 9 Normandy High School 43,780 39 New Knoxville High School 18,936 10 Boardman High School 42,694 40 Lorain High School 18,638 11 Clyde High School 42,506 41 Villa Angela-St Joseph High School 18,611 12 Vermilion High School 40,693 42 Padua Franciscan High School 18,419 13 Hudson High School 37,742 43 Massillon Washington High School 18,358 14 Berea-Midpark High School 35,157 44 Medina High School 18,183 15 West Holmes High School 33,389 45 Clay High School 17,782 16 Hiland High School 31,993 46 Austintown Fitch High School 17,586 17 Magnificat High School 31,952 47 Grandview Heights High School 17,562 18 Coldwater High School 31,815 48 Orrville High School 17,118 19 Miamisburg High School 29,720 49 Brookville High School 17,092 20 North Royalton High School 28,001 50 Roger Bacon High School 16,427 21 Big Walnut High School 27,664 51 Marysville High School 16,035 22 Centerville High School 27,066 52 Fort Loramie High School 15,748 23 Cleveland Heights High School 26,977 -

Ohio Contract User List 2016-2017

Ohio Contract Usage 2016-2017 MHEC CONTRACTS leverage the potential volume of the region’s purchasing power, while saving entities time and money by simplifying the procurement process and negating the need to conduct a competitive sourcing event. By offering a turnkey solution with the ability to tailor the already negotiated contract to match the entity’s specific needs and2 requirements,0162017 MHEC contracts shift some of the negotiating power back to the entities. Additionally, because of MHEC’s statutory status, many of these contracts can also be adopted for use by K-12 districts and schools, as well as cities, states and local governments. Smaller institutions benefit from these contracts as they allow these institutions to receive some pricing and terms normally reserved for larger institutions. Committee members participate in the negotiations, sharing strategies, and tactics on dealing with specific contractual issues and vendors. ANNUAL HARDWARE CONTRACTS Tiffin University Bridgeport Exempted Village Cuyahoga Valley Christian School District Academy Higher Education Union Institute and University REPORT Bristol Local School District Dover City School District Antioch University University of Cincinnati Brookville Local School East Palestine City School Ashland University University of Dayton to the Member States District District Bluffton University University of Findlay Brown Local School District Eaton Community Schools Capital University University of Mount Union Buckeye Joint Vocational Fenwick High School Case Western Reserve University of Rio Grande School Field Local Schools University University of Toledo Canfield Local School District Franklin Local School District Cedarville University Walsh University Centerville City Schools Fuchs Mizrachi School Cleveland State University Zane State College Central Junior High School Gallia-Jackson-Vinton Joint College of Wooster Central Primary School Village School District God’s Bible School and HARDWARE CONTRACTS Child Focus, Inc.