A Catholic's Dissent from the Bishops' Immigration Policy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

News Release Michigan State University Commencement

NEWS RELEASE MEDIA CONTACT: Kristen Parker, University Relations, (517) 353-8942, [email protected] MICHIGAN STATE UNIVERSITY COMMENCEMENT/CONVOCATION SPEAKERS 1907 Theodore Roosevelt, U.S. president 1914 Thomas Mott Osborn 1915 David Starr Jordan, Chancellor, Leland Stanford Junior University 1916 William Oxley Thompson, president, Ohio State University 1917 Samuel M. Crothers 1918 Liberty H. Bailey 1919 Robert M. Wenley, University of Michigan 1920 Harry Luman Russell, dean, University of Wisconsin 1921 Woodridge N. Ferris 1922 David Friday, MSU president 1923 John W. Laird 1924 Dexter Simpson Kimball, dean, Cornell University 1925 Frank O. Lowden 1926 Francis J. McConnell 1931 Charles R. McKenny, president, Michigan State Normal College 1933 W.D. Henderson, director of university extension, University of Michigan 1934 Ernest O. Melby, professor of education, Northwestern University 1935 Edwin Mims, professor of English, Vanderbilt University 1936 Gordon Laing, professor, University of Chicago 1937 William G. Cameron, Ford Motor Co. 1938 Frank Murphy, governor of Michigan 1939 Howard C. Elliott, president, Purdue University 1940 Allen A. Stockdale, Speakers’ Bureau, National Assoc. of Manufacturers 1941 Raymond A. Kent, president, University of Louisville 1942 John J. Tiver, president, University of Florida 1943 C.A. Dykstra, president, University of Wisconsin 1944 Howard L. Bevis, president, Ohio State University 1945 Franklin B. Snyder, president, Northwestern University 1946 Edmund E. Day, president, Cornell University 1947 James L. Morrill, president, University of Minnesota 1948 Charles F. Kettering 1949 David Lilienthal, chairperson, U.S. Atomic Commission 1950 Alben W. Barkley, U.S. vice president (For subsequent years: S-spring; F-fall; W-winter) 1951-S Nelson A. -

2010 Tiaa-Cref Theodore M. Hesburgh Award for Leadership Excellence

2010 TIAA-CREF THEODORE M. HESBURGH AWARD FOR LEADERSHIP EXCELLENCE Vision is what leadership is all about. Leadership is how you bring that vision into reality. If you want people to go with you, you have to share a vision. Reverend Theodore M. Hesburgh, C.S.C., President Emeritus, University Of Notre Dame William E. Kirwan CHANCELLOR, UNIVERSITY SYSTEM OF MARYLAND 2010 TIAA-CREF THEODORE M. HESBURGH AWARD WINNER Presenting the In looking at leaders in higher education who best exemplify Father Hesburgh’s shining example of visionary thinking, integrity, and a selfless commitment to TIAA-CREF Hesburgh award the greater good, one name becomes clear: Dr. William E. Kirwan. The TIAA-CREF Theodore M. Hesburgh Award for Leadership Excellence TIAA-CREF is proud to salute Dr. Kirwan as the 2010 recipient of the is named in honor of Reverend Hesburgh, C.S.C., president emeritus of the TIAA-CREF Theodore M. Hesburgh Award for Leadership Excellence. University of Notre Dame and former member of the TIAA-CREF Board of Over his nearly half-century as an educator, administrator, and community Overseers for 28 years. leader, Dr. Kirwan has been a passionate advocate for a broad spectrum of major issues facing higher education. He gives selflessly of his abilities and The award recognizes leadership and commitment to higher education and energy to encourage the sharing and shaping of ideas and practices across contributions to the greater good. It is presented to a current college or Maryland, the United States, and beyond. university president or chancellor who embodies the spirit of Father Hesburgh, his commitment and contributions to higher education and society. -

Hesburgh Scholar Program

HESBURGH SCHOLAR PROGRAM Inspired by the work of Rev. Theodore Hesburgh, CSC, the Hesburgh Scholar Program challenges students to use their talents to aid in the construction of a world where justice, peace and love prevail. Rev. Theodore Hesburgh, CSC: Renowned Leader A priest of the Congregation of Holy Cross, Rev. Theodore Hesburgh, CSC, is considered one of the nation’s truly great leaders. Committed to nurturing spiritual values, Fr. Hesburgh has substantially shaped and articulated America’s conscience on numerous social issues. Fr. Hesburgh served as President of the University of Notre Dame for 35 years (1952-1987), but his work was not limited to the University. His remarkable achievements in the public sector include service on 16 Presidential Commissions in the areas of civil rights, peaceful uses of atomic energy, and Third World development. Widely recognized for his work, he has received over 150 honorary degrees, the Congressional Gold Medal, and the Medal of Freedom. Inspired by the work of Fr. Hesburgh, the Rev. Theodore Hesburgh, CSC Scholar Program challenges students to use their talents to aid in the construction of the world “where justice, peace and love prevail.” What is the Hesburgh Scholar Program? The Rev. Theodore Hesburgh, CSC Scholar Program is designed to challenge the most gifted and motivated students in a demanding course of studies. The Hesburgh Scholar Program not only requires the development of the student’s abilities in all areas of the academic curriculum, but also seeks to further his overall development through involvement in various service-oriented and extracurricular activities. Admissions Criteria and Expectations Members of the Hesburgh Scholar Program are invited to apply at the end of the first semester of their freshman or sophomore year. -

Father Ted's Obituary

For Immediate Release Feb. 27, 2015 Father Theodore Hesburgh of Notre Dame dies at age 97 Rev. Theodore M. Hesburgh, C.S.C., president of the University of Notre Dame from 1952 to 1987, a priest of the Congregation of Holy Cross, and one of the nation’s most influential figures in higher education, the Catholic Church, and national and international affairs, died at 11:30 p.m. Thursday (Feb. 26) at Holy Cross House adjacent to the University. He was 97. “We mourn today a great man and faithful priest who transformed the University of Notre Dame and touched the lives of many,” said Rev. John I. Jenkins, C.S.C., Notre Dame’s president. “With his leadership, charisma and vision, he turned a relatively small Catholic college known for football into one of the nation’s great institutions for higher learning. “In his historic service to the nation, the Church and the world, he was a steadfast champion for human rights, the cause of peace and care for the poor. “Perhaps his greatest influence, though, was on the lives of generations of Notre Dame students, whom he taught, counseled and befriended. “Although saddened by his loss, I cherish the memory of a mentor, friend and brother in Holy Cross and am consoled that he is now at peace with the God he served so well.” In accord with Father Hesburgh’s wishes, a customary Holy Cross funeral Mass will be celebrated in the Basilica of the Sacred Heart at Notre Dame in coming days for his family, Holy Cross religious, University Trustees, administrators, and select advisory council members, faculty, staff and students. -

Vita Michigan State University Department of History East Lansing

Vita William James Schoenl Professor Michigan State University Department of History East Lansing, Michigan 48824 Telephone: (517) 351-0456 Educational Background: Ph.D., History, Columbia University, New York, N.Y., 1968 M.A., History, Columbia University, 1964 B.S., Mathematics, Canisius College, Buffalo, N.Y., 1963 Career Employment: 1989- Professor of History, Michigan State University 1978-1989 Professor of Humanities, Michigan State University 1972-1978 Associate Professor of Humanities, MSU 1968-1972 Assistant Professor of Humanities, MSU Books Published: Editor, New Perspectives on the Vietnam War: Our Allies’ Views (Lanham, New York, and Oxford: University Press of America, 2002) Author, C.G. Jung: His Friendships with Mary Mellon and J. B. Priestley (Wilmette: Chiron Publications, 1998) [NOTE: Chiron is the leading publisher of books in Jungian studies in the United States.] Editor, Major Issues in the Life and Work of C. G. Jung (Lanham, New York, and London: University Press of America, 1996) Author, The Intellectual Crisis in English Catholicism (New York and London: Garland Publishing, 1982) [NOTE: a book in the Garland Series in Modern British History, edited by Peter Stansky and Leslie Hume, Stanford University.] Contributor of numerous articles and reviews to professional journals. The American Historical Review, The Journal of Analytical Psychology, Church History, The Catholic Historical Review, Victorian Studies, and Choice have published my reviews. 1 I have given papers, chaired sessions, and served as commentator at annual meetings of the American Historical Association, Catholic Historical Association, American Society of Church History, Midwest Conference on British Studies, and Michigan Academy of Arts and Sciences. I have also been a member of each of these professional associations. -

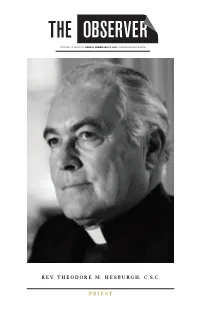

Rev. Theodore M. Hesburgh, C.S.C. Priest

VOLUME 48, ISSUE 98 | FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 27, 2015 | NDSMCOBSERVER.COM REV. THEODORE M. HESBURGH, C.S.C. PRIEST GOD , COUNTRY, NOTRE DAME In memoriam of the impact Rev. Theodore M. Hesburgh had on the Notre Dame Family, the Nation and the Catholic Church. r. Theodore Hesburgh, whose unprecedented 35-year tenure as president of Notre Dame revolutionized the University, making him Fone of the most influential figures in higher education, and whose dedication to social issues brought him worldwide recognition, died Feb. 26. He was 97. When Hesburgh became the 15th president of Notre Dame in 1952, the University was comprised of all males. It was owned and operated by the Theodore Bernard Hesburgh Holy Cross Order with an endowment of $9 million and yearly student aid to tuition at $20,000. When Hesburgh retired in 1987, Notre Dame had grown its student body to include both men and women. He transitioned the school’s governance to a mixed board of lay and religious trustees that still operates the University today. The endowment had grown to $350 million over 35 years and student aid hit $40 million. His presidency transformed the school into the top-tier educational institution it is today. But Hesburgh was, first and foremost, a simple priest. “I would say if there is one thing that my whole life has been dedicated to, I’ve been a priest now for about 70 years, and I would hope they remember me as a priest,” Hesburgh told The Observer in May 2013. “‘Fr. Ted’ is the best title I have. -

Georgetown at Two Hundred: Faculty Reflections on the University's Future

GEORGETOWN AT Two HUNDRED Content made available by Georgetown University Press and Digital Georgetown Content made available by Georgetown University Press and Digital Georgetown GEORGETOWN AT Two HUNDRED Faculty Reflections on the University's Future William C. McFadden, Editor Georgetown University Press WASHINGTON, D.C. Content made available by Georgetown University Press and Digital Georgetown Copyright © 1990 by Georgetown University Press All Rights Reserved Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Georgetown at two hundred : faculty reflections on the university's future / William C. McFadden, editor. p. cm. ISBN 0-87840-502-X. — ISBN 0-87840-503-8 (pbk.) 1. Georgetown University—History. 2. Georgetown University— Planning. I. McFadden, William C, 1930- LD1961.G52G45 1990 378.753—dc20 90-32745 CIP Content made available by Georgetown University Press and Digital Georgetown FOR THE GEORGETOWN FAMILY — STUDENTS, FACULTY, ADMINISTRATORS, STAFF, ALUMNI, AND BENEFACTORS, LET US PRAY TO THE LORD. Daily offertory prayer of Brian A. McGrath, SJ. (1913-88) Content made available by Georgetown University Press and Digital Georgetown Content made available by Georgetown University Press and Digital Georgetown Contents Foreword ix Introduction xi Past as Prologue R. EMMETT CURRAN, S J. Georgetown's Self-Image at Its Centenary 1 The Catholic Identity MONIKA K. HELLWIG Post-Vatican II Ecclesiology: New Context for a Catholic University 19 R. BRUCE DOUGLASS The Academic Revolution and the Idea of a Catholic University 39 WILLIAM V. O'BRIEN Georgetown and the Church's Teaching on International Relations 57 Georgetown's Curriculum DOROTHY M. BROWN Learning, Faith, Freedom, and Building a Curriculum: Two Hundred Years and Counting 79 JOHN B. -

Memorandum, President Nixon Meeting with Commission on an All

「下情三 幸井出丁離 日Cう∪$蚤 WASトロ卜」G千〇予」 M丑MORANDUM FOR THE PRESIDFNT SUBJECT: Meeting with Commission on An A11細Volu.n七eer Arlned Fo].Ce February 2l, 1970 1l:00A.M. Cabine七RooIn PURPOSE Requested by Martin Anderson to allow thc Commission tO PreSent its COmPleted repOrt・ エI. BACKGROUND A. This was a 。working commission・ 。 The members particIPated deep]y in the prepara七ion of the study, and did not rely exclusive]y, as many commissions do, On the staff・ During the las七year they SPent OVer 100 hours and many long weekends in. Commission. meetings. There was∴a gene]:al feeling m the Commission that the issue r thcy were dealillg Wi七h was one of great importance・ They Were Vitally concerned with national security, and onlv after a long, SOul輸SCarChing examination of the pros and cons did they unanimously conclude that 。the nationls interes七s w丑l be bett e聖畦上狸聖 all録VOlunte∋er f。rCe, SuPPOr七ed bv an .′ effective standby draft, than by a mixed fol.Ce Of voluntecrs and conscripts. (and) that a v0lun王eer force will not JeOPal.dizc na七ional secul.ity, and. wi11 haヽ′e a beneficia‘し effect on Lhc milゴtary aLS Well as the rest of our∴S。Ciety. 。 Their basic∴工・ccOmmendations are: (l〉 Raise basic pay for mili七ary personnel in the first two years of seユ:Vice. The estimated cost is about $3. 3 billion a, year. (Z) M諒e comprehcnsive improvements in condiLions Of military sel.Vice・ (3) 曲鉦ablish a. sしa朝航y draft. _Z- Tom Gates was particularly effective as Chairman・ Each Commission mem-ber is a一一star一一inhis own right, the issues were con七roversial, yet Gates managed to sm0Othly and de工tly keep the Commission moving to a una,n王mous report. -

Notre Dame College Prep

Notre Dame College Prep COMMITTED TO FORMING MEN OF FAITH, SCHOLARSHIP AND SERVICE School Notre Dame College Prep is a Roman Catholic college preparatory school and has educated more than 12,000 young men since its founding in 1954. Located in Niles, Illinois, on 28 wooded acres, Notre Dame Notre Dame currently enrolls over 800 students. Our students come from Chicago and 29 different suburbs.Notre College Prep Dame’s approach to education is holistic. We educate the mind, but never at the expense of the heart. 7655 West Dempster Street The instructional programs at Notre Dame have distinct levels of challenge: Advanced Placement, Honors, Niles, Illinois 60714 College Prep Core, and the Andre Program. Each level is geared to prepare our students for college Phone: 847-965-2900 admission. Rigorous courses of study are designed to meet the educational needs of our diverse student Fax: 847-965-2975 body and are tailored to provide challenging educational experiences for our students. www.nddons.org Mission CEEB/ACT School Code: 141-063 Under the patronage of Mary, Notre Dame College Prep is a secondary school committed to educating PRESIDENT young men to be gentlemen of faith, scholarship, and service in an inclusive, family-oriented community. Mr. Ralph J. Elwart Faithful to the Roman Catholic tradition and inspired by Gospel values, we prepare students to be lifelong learners and to lead lives of integrity. PRINCIPAL Mr. Daniel E. Tully Hesburgh Scholar Program COUNSELING CENTER Named in honor of University of Notre Dame President Emeritus Rev. Theodore Hesburgh, CSC, this program Mr. Steve Murray, Director is designed to challenge the most gifted and motivated student with a demanding course of studies. -

1 the Current State of Catholic Higher Education

N o t e s 1 The Current State of Catholic Higher Education 1 . John Paul II, Fides et Ratio (Boston: Pauline Books & Media, 1998). 2 . Alice Gallin, O. S. U., ed., American Catholic Higher Education: The Essential Documents, 1967–1990 (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 1992), 7. 3 . Edward Manier and John Houck, eds., Academic Freedom and the Catholic University (Notre Dame, IN: Fides Publishers, 1967); Neil G. McCluskey, S. J., ed., The Catholic University: A Modern Appraisal (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 1970); Paul L. Williams, ed., Catholic Higher Education: Proceedings of the Eleventh Convention of the Fellowship of Catholic Scholars (Pittston, PA: Northeast Books, 1989); George S. Worgul Jr., Issues in Academic Freedom (Pittsburgh, PA: Duquesne University Press, 1992). 4 . Recent American historians have documented, from a purely historical perspec- tives, the severance of academic inquiry from religious belief. See George M. Marsden, The Soul of the American University: From Protestant Establishment to Established Nonbelief (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994); James Tunstead Burtchaell, The Dying of the Light: The Disengagement of Colleges and Universities from Their Christian Churches (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1998); Julie A. Reuben, The Making of the Modern University: Intellectual Transformation and the Marginalization of Morality (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1996); Jon Roberts and James Turner, The Sacred and the Secular University (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2000); David J. O’Brien, From the Heart of the American Church: Catholic Higher Education and American Culture (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1994); and Philip Gleason, Contending with Modernity: Catholic Higher Education in the Twentieth Century (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995). -

Mayor Marvin's Column

MAYOR MARVIN'S COLUMN At this time of year, I am a keen observer of commencement addresses, having spent weeks writing one to deliver at the Bronxville High school graduation of 2008. It was the honor of my life. Tlus past month, I was struck fIrst by the number of extremely accomplished, ground breaking, brave people who were disinvited or respectfully backed out as commencement speakers after student and/or faculty protests. Snlith College nlissed out on one of the world's most pronlinent and powerful women, Christine Legarde, because, "she leads an imperialistic and patriarchal system," according to student organizers and just listening to her would be paramount to endorsement. What a lost moment to hear the triumphs and travails of a fellow woman who has navigated a traditionally male sphere. To her credit, the President of Stnith College, KatWeen McCartney, refused to rescind the invitation stating that she is, "committed to leading a college where differing views can be heard and debated with respect." However, Ms. Legarde cancelled given the protests. A similar situation occurred at Rutgers when Condoleeza Rice gracefully bowed out after not only students but the faculty council said just listening to her, "was encouraging a world that justifIes torture," Completing the First Amendment repression hat trick, Haverford College caused Robert Burgeneau, former Chancellor of the University of California, Berkeley to withdraw as commencement speaker. Students wanted him, as condition of attendance, to formally apologize for allowing police to use batons at an Occupy protest in 2011. Truth be told, Chancellor Burgeneau actually launched an investigation after being disturbed by a videotape of the baton use. -

Rev. Theodore M. Hesburgh, C.S.C., President, University of Notre Dame, at Duquesne University's Centennial Celebration, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, October 3, 1978)

., (Address given by the Rev. Theodore M. Hesburgh, C.S.C., President, University of Notre Dame, at Duquesne University's Centennial Celebration, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, October 3, 1978) THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY IN THE MODERN CONTEXT If this subject were being discussed in the 13th Century, we could dispense with the adjective Catholic in the title, since to speak of universities in the first century or two of their existence in the Western world would be to speak of them as Catholic, since there were no others. Today, of course, the situation is quite the opposite. Catholic universities are the exception, rather than the rule, in the world of universities. In Europe, where universities began and multiplied, as Catholic, there remains today just one of those great originals, Louvain. I say one, although it has recently separated by language, the French-speaking one becoming Louvain-la-Neuve. .. There are five Instituts Catholiques, French Catholic universities in the country of the university's origin. Italy, the country that saw the first student founded and student administered university in Bologna the !tali.ans will also say it is the oldest of all -- now has one true Catholic university, Sacro Cuore in Milan. I studied at the reasonably ancient - mid 16th Century - Gregorian University in Rome, but it and its ancient sister universities there have only ecclesi.astical faculties theology, philosophy, Canon Law, etc. -- and would not be considered universities in the secular sense. - 2 - Spain and Portugal, the countries of ancient and distinguished Mediaeval Catholic universities, like Alcala and Coimbra, now have only newly-created Catholic universities, such as Salamanca, Navarra, and Lisbon, which count their life spans in decades, not centuries.