Joyce Cary's Trilogies Joyce Cary's Trilogies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

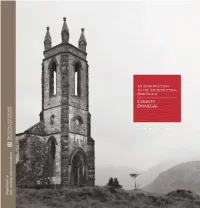

AN INTRODUCTION to the ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE of COUNTY DONEGAL

AN INTRODUCTION TO THE ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE of COUNTY DONEGAL AN INTRODUCTION TO THE ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE of COUNTY DONEGAL COUNTY DONEGAL Mount Errigal viewed from Dunlewey. Foreword County Donegal has a rich architectural seventeenth-century Plantation of Ulster that heritage that covers a wide range of structures became a model of town planning throughout from country houses, churches and public the north of Ireland. Donegal’s legacy of buildings to vernacular houses and farm religious buildings is also of particular buildings. While impressive buildings are significance, which ranges from numerous readily appreciated for their architectural and early ecclesiastical sites, such as the important historical value, more modest structures are place of pilgrimage at Lough Derg, to the often overlooked and potentially lost without striking modern churches designed by Liam record. In the course of making the National McCormick. Inventory of Architectural Heritage (NIAH) The NIAH survey was carried out in phases survey of County Donegal, a large variety of between 2008 and 2011 and includes more building types has been identified and than 3,000 individual structures. The purpose recorded. In rural areas these include structures of the survey is to identify a representative as diverse as bridges, mills, thatched houses, selection of the architectural heritage of barns and outbuildings, gate piers and water Donegal, of which this Introduction highlights pumps; while in towns there are houses, only a small portion. The Inventory should not shopfronts and street furniture. be regarded as exhaustive and, over time, other A maritime county, Donegal also has a rich buildings and structures of merit may come to built heritage relating to the coast: piers, light. -

Field Day Revisited (II): an Interview with Declan Kiberd1

Concentric: Literary and Cultural Studies 33.2 September 2007: 203-35 Field Day Revisited (II): An Interview with Declan Kiberd1 Yu-chen Lin National Sun Yat-sen University Abstract Intended to address the colonial crisis in Northern Ireland, the Field Day Theatre Company was one of the most influential, albeit controversial, cultural forces in Ireland in the 1980’s. The central idea for the company was a touring theatre group pivoting around Brian Friel; publications, for which Seamus Deane was responsible, were also included in its agenda. As such it was greeted by advocates as a major decolonizing project harking back to the Irish Revivals of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Its detractors, however, saw it as a reactionary entity intent on reactivating the same tired old “Irish Question.” Other than these harsh critiques, Field Day had to deal with internal divisions, which led to Friel’s resignation in 1994 and the termination of theatre productions in 1998. Meanwhile, Seamus Deane persevered with the publication enterprise under the company imprint, and planned to revive Field Day in Dublin. The general consensus, however, is that Field Day no longer exists. In view of this discrepancy, I interviewed Seamus Deane and Declan Kiberd to track the company’s present operation and attempt to negotiate among the diverse interpretations of Field Day. In Part One of this transcription, Seamus Deane provides an insider’s view of the aspirations, operation, and dilemma of Field Day, past and present. By contrast, Declan Kiberd in Part Two reconfigures Field Day as both a regional and an international movement which anticipated the peace process beginning in the mid-1990’s, and also the general ethos of self-confidence in Ireland today. -

74 Morris Joyce Cary

JOYCE CARY – LIBERAL TRAdiTIONS ‘Britain is profoundly a liberal state. Its dominating mind has been liberal for more than a century.’ These words were written by a novelist whose works Prisoner of Grace, Except the Lord, and Not Honour More explore the British liberal tradition against the backdrop of the great electoral landslide which gave the Liberal Party its overwhelming majority in 1906. Chester Nimmo, the main protagonist of this ‘political trilogy’, is a member of the resulting New Liberalism which took hold as a result. John Morris celebrates the work of the English novelist Joyce Cary, whose work is rooted in Liberal ideas. 16 Journal of Liberal History 74 Spring 2012 JOYCE CARY – LIBERAL TRAdiTIONS orn in Londonderry in The African Witch was made a Book and guide the soul – politics does 1888, Arthur Joyce Lunel Society choice, and he was finally the same thing for the body. God Cary was named after recognised as a fine novelist with is a character, a real and consistent his mother Charlotte the publication of Mister Johnson in being, or He is nothing. If God did Joyce in the Anglo-Irish 1939, which was also based on his a miracle He would deny His own Btradition of his class. Following the experiences in West Africa. nature and the universe would sim- Irish land reforms of the 1880s, the Though now largely forgot- ply blow up, vanish, become noth- family, now stripped of its lands, ten, Joyce Cary was the author of ing’. 4 Cary’s conviction instead was settled in London, where Charlotte many novels which were as highly that beauty and human love proved died of pneumonia in 1898 when regarded as those of his contempo- the existence ‘of some transcenden- Joyce was nine years old and his raries Graham Greene and Evelyn tal spiritual reality with which a brother Jack just six. -

MORAL ELEMENTS in the NOVELS of JOYCE CARY Thesis Presented

1028 UNIVERSITY D'OTTAWA ~ ECOLE DES GRADUES MORAL ELEMENTS IN THE NOVELS OF JOYCE CARY Thesis presented to the Faculty of Arts of the University of Ottawa through the Department of English as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. UNIVERSITY OF OTTAWA - SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES UMI Number: DC53804 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI® UMI Microform DC53804 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 UNIVERSITE D'OTTAWA - ECOLE DES GRADUES ACKNOWLEDGMENT This thesis was prepared under the guidance of Dr- Emmett O'Grady of the University of Ottawa, Department of English. The writer would like to express his thanks to Dr. O'Grady for the interest he has shown in the thesis and for the suggestions he has made for its improvement. UNIVERSITY OF OTTAWA ~ SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES UNIVERSITE D'OTTAWA ~ ECOLE DES GRADUES CURRICULUM STUDIORUM William Ewing MacDonald Lindsay was born in Edinburgh, Scotland on March 19, 1915- He has been granted the following academic degrees: Bachelor of Arts (University of Toronto, 19^3); Master of Arts in English (St. -

Creative Imagination in Joyce Cary's Trilogies E

Loma Linda University TheScholarsRepository@LLU: Digital Archive of Research, Scholarship & Creative Works Loma Linda University Electronic Theses, Dissertations & Projects 6-1979 Creative Imagination in Joyce Cary's Trilogies E. Christian Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsrepository.llu.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, and the Poetry Commons Recommended Citation Christian, E., "Creative Imagination in Joyce Cary's Trilogies" (1979). Loma Linda University Electronic Theses, Dissertations & Projects. 550. https://scholarsrepository.llu.edu/etd/550 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by TheScholarsRepository@LLU: Digital Archive of Research, Scholarship & Creative Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loma Linda University Electronic Theses, Dissertations & Projects by an authorized administrator of TheScholarsRepository@LLU: Digital Archive of Research, Scholarship & Creative Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract CREATIVE IMAGINATION IN JOYCE CARY'S TRILOGIES by E. Christian This thesis describes Joyce Cary's theories of creative imagination and how the characters in his two trilogies reflect those theories. To Cary, creative imagination is essential for society's improvement. Re believes that everyone--not just artists and writers--can have creative imagination, and in his novels he shows the results of living with and without it. Joyce Cary was born in 1888, in Ireland. His mother died when he was nine, but his close-knit family gave him the security he needed to develop his creativity. As a boy he voraciously read adventure stories and led a gang. Throughout his life he dealt creatively with his problems. In public school, weak from previously poor health, he won his classmates' favor by telling them stories and forcing himself to master swimming, football, and boxing. -

Making Literary Heritage Accessible to Young People

Making literary heritage accessible to young people The Unwrapping Words project has changed the lives of young people from deprived areas by empowering their creative talents and gifts through art, music, literature and film The Moville and District Family Resource Centre supports fami- lies and individuals in the Inishowen peninsula of County Donegal, Ireland. In 2015, it brought together marginalised young people from Inishowen and Derry City to explore the Photo: © Moville and District Family Resource Centre literary heritage of this North-West border region of Ireland. The ‘Unwrapping Words’ project looked at the works of writers Key facts and figures such as Joyce Cary, Frank McGuinness, Bridget O’Toole and Erasmus+ Participants: Countries: Mabel Colhoun, who are connected to Inishowen through their 48 2 books, family, themes, sense of place or geographical refer- Field: Youth ence in their work. Participants reinterpreted and contextual- Action: Strategic ised the works, with multimedia technology employed to Partnerships EU grant: Project duration: encourage participation and creativity. € 23,288 2015-2016 The project coordinator, Michael McDermott, explained: Project title We wanted to reinterpret our own cultural Unwrapping Words identity through the eyes of young people ‘ from two urban and rural areas facing social and economic deprivation.’ Participants created a mural piece, located in a cross- border area that will be directly impacted by Brexit which will see the United Kingdom withdrawing from the European Union. The mural is seen on average by 10 000 cars that pass the site each week. Other activi- ties included the production of a rap music CD produced by the participants themselves that deals with issues affecting their own lives. -

Donegal -- Derry

Chapter 3 THE NORTH-WEST counties Roscommon -- Leitrim -- Cavan -- Fermanagh -- west Tyrone -- Donegal -- Derry ROSCOMMON Rathcrogan West of Edgeworthstown (which has now reverted to its old name of Mostrim) on the N5 Longford-Castlebar road [1] , is Rathcrogan , Co.Roscommon. As Cruachan this was the site of the royal palace of Queen Maeve , and here were sown the seeds of the Táin, the 'Cattle Raid of Cooley ' [2] . Maeve ( Medb ), Queen of Connacht, and her consort, Ailill, are in bed in their palace on one of the mounds still to be seen at Rathcrogan, and he, with mixed humour and malice, muses: 'You are better off today than when I married you.' Maeve is indignant, and responds with an account of her genealogy, her battle- prowess, and the number of soldiers of her own that she had before she married Ailill. Then she seems to change tack, admitting that she had 'a strange bride-gift such as no woman before had asked of the men of Ireland, that is, a man without meanness, jealousy, or fear': Ailill had brought with him those gifts, he was just such a man, equal to herself in generosity and grace. One can almost see Ailill, pleased, relaxing and lowering his guard. However, Maeve continues; she had brought with her 'the breadth of your face in red gold, the weight of your left arm in bronze. So, whoever imposes shame or annoyance or trouble on you, you have no claim for compensation or honour-price other than what comes to me -- for you are a man dependant on a woman.' Ailill replies loftily that his two brothers were kings, one of Temair (Tara), the other of Leinster, and he had only decided to marry Maeve, and thus become a king himself, 'because I heard of no province in Ireland ruled by a woman save this province alone.' Scholars have suggested that this is the mythological representation of an historical shift from matriarchy to political patriarchy, as well as from goddess to god. -

Postcolonial Literatures in English

The Cambridge Introduction to Postcolonial Literatures in English The past century has witnessed an extraordinary flowering of fiction, poetry and drama from countries previously colonised by Britain, an output which has changed the map of English literature. This introduction, from a leading figure in the field, explores a wide range of Anglophone postcolonial writing from Africa, Australia, the Caribbean, India, Ireland and Britain. Lyn Innes compares the ways in which authors shape communal identities and interrogate the values and representations of peoples in newly independent nations. Placing its emphasis on literary rather than theoretical texts, this book offers detailed discussion of many internationally renowned authors, including Chinua Achebe, James Joyce, Les Murray, Salman Rushdie and Derek Walcott. It also includes historical surveys of the main countries discussed, a glossary, and biographical notes on major authors. Lyn Innes provides a rich and subtle guide to an array of authors and texts from a wide range of sites. C. L. Innes is Emeritus Professor of Postcolonial Literatures at the University of Kent. She is the author of, among other books, AHistory of Black and Asian Writing in Britain (Cambridge, 2002). Cambridge Introductions to Literature This series is designed to introduce students to key topics and authors. Accessible and lively, these introductions will also appeal to readers who want to broaden their understanding of the books and authors they enjoy. r Ideal for students, teachers, and lecturers r Concise, yet packed with essential information r Keysuggestions for further reading Titles in this series: Christopher Balme The Cambridge Introduction to Theatre Studies Eric Bulson The Cambridge Introduction to James Joyce Warren Chernaik The Cambridge Introduction to Shakespeare’s History Plays John Xiros Cooper The Cambridge Introduction to T. -

Books for Children

~endix I Books for children IRISH books specifically written for children begin with Maria Edgeworth's well-known moral, educational stories which still appeal to children fortunate enough to have them read aloud to them. There is, however, more fantasy in the fairy stories of Granny s Wonderful Chair and the Stories It Told (1857) by Frances Brown (1816-79) the blind Donegal poet and novelist. Following Standish O'Grady's Irish stories came those of Ella Young (1865-1951). Born in County Antrim, she became an active Republican, learned Irish, and wrote The Coming of Lugh (1909) and Celtic Wonder-Tales (1910). Her later work The Wonder Smith and His Son (1927) and The Unicorn with Silver Shoes (1932) have a touch of pleasing fantasy about them. Another woman writer who produced stories for children was Winifred Letts (b. 1882), whose poems, in Songs from Leinster (1913) and More Songs from Leinster (1926), and an autobiography, Knockmaroon (1933), are worth reading. In more recent times Patricia Lynch (1900-72) wrote many very popular books for children, particularly her Turf-Cutter's Donkey Series which began in 1935, and the books about Brogeen the leprechaun, which began in 1947. Her writings, warmhearted and skilful, have been widely translated. A Storytellers Childhood (1947) is a masterly rendering of her own youth, to be compared, perhaps, with an earlier masterpiece, Hannah Lynch's Auto biography of a Child (1899). The Singing Cave (1959) by Eilis Dillon (b. 1920) is the best of this writer's work for children. She has also written a lively historical novel Across the Bitter Sea (1973) with a sequel Blood Relations (1977). -

1988 | Joyce Cary Remembered: in Letters and Interviews by His Family and Others, ISSN 0954-3392

Rowman & Littlefield, 1988 | 9780389208129 | 273 pages | Barbara Fisher | 1988 | Joyce Cary Remembered: In Letters and Interviews by His Family and Others, ISSN 0954-3392 The story begins with the fact that Tutin wants to leave his wife and three children after sixteen years of married life. We will write a custom essay sample on. âœPeriod Pieceâ by Joyce Cary. or any similar topic specifically for you. Do Not Waste Your Time. Clare does not object and Tutin feels comfortable until his mother-in-law comes to London and makes a scene. At first she breaks into Tutinâ™s office and says that he is selfish. Tutin does not share this point of view and he goes to Clare to have it out with her. Then Tutin learns that Mrs. Beer has visited Phyllis. Then thereâ™s a description of their family life seven years after the events. Tutin is happy enough not to feel sorry about his fate. The author ridicules old Mrs. Beer, who thinks that she is the one who has made Tutin return to Clare. The text under stylistic analysis is written by Joyce Carry. It deals with the author's emotions and feelings towards Clare, Tutin's wife, who lost her. The text under stylistic analysis is written by Joyce Carry. It deals with the authorâ™s emotions and feelings towards Clare, Tutinâ™s wife, who lost her husband. This text is about one businessman Tutin who tell in love with his secretary and wanted a divorce. And having known this description we can say it was a bossy person who liked to give orders to other people. -

Amongst Empires: a Short History of Ireland and Empire Studies in International Context

01-cleary-pp11-57 5/8/07 9:52 PM Page 11 Joe Cleary Amongst Empires: A Short History of Ireland and Empire Studies in International Context This essay begins with a summary overview of emergent intellectual trends that are redefining the study of empire today. It then charts a history of modern Irish scholarship on empire, discussing the achievements and limitations of Atlantic History, Commonwealth History, and postcolonial studies.1 The piece closes with a discus- sion of how Empire Studies in Ireland might be reoriented in the future so as to deal not only with Irish responses to the now-vanished British Empire but also to the wider European imperial system and to the American neo-imperialism that emerged in its wake. Empire Studies and the Crises of American Imperialism Not so long ago the historiography of empire was a sedate enter- prise with the air of a somewhat inconsequential intellectual tidy-up operation in which mostly Western historians deliberated the char- acter of European empires gone the way of Nineveh and Tyre. For a time, the very word “imperialism” seemed even to be becoming obsolete due to the collapse of Marxist theory’s intellectual stock . These fields obviously do not cover the entire gamut of Irish scholarship on empire. Several other fields might be discussed, including the economic history of empire, scholarship on Northern Ireland, studies of empire in eighteenth- and nine- teenth-century contexts, and so on. However, they do represent major concentra- tions of work and thus represent significant contributions to the development of Empire Studies in Ireland. -

Reference Resources in Irish Literature by JAMES BRACKEN

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by KnowledgeBank at OSU Choice, Vol. 39, No. 2, 2001, pp.229-242. ISSN: 1523-8253 http://www.ala.org/ http://www.cro2.org/default.aspx Copyright © 2001American Library Association. BIBLIOGRAPHIC ESSAY Reference Resources in Irish Literature BY JAMES BRACKEN James Bracken is acting assistant director for Main Library Research and Reference Services at Ohio State University. The recent publication of Nobel laureate Seamus Heaney's Beowulf: A New Verse Translation suggests some of the difficulties in attempting to distinguish an Irish identity in English literature. This Beowulf can be interpreted as a clever trick of literary appropriation: if, as it has been said, the great works of Irish literature have been written in English, in Heaney's Beowulf one of England's literary treasures is made Irish. Just what constitutes Irish literature often seems to be as much a matter of semantics as national identity. In the Oxford Companion to Irish Literature, editor Robert Welch argues that Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing, edited by Seamus Deane, the standard by which all subsequent anthologies of Irish literature must be measured, confronts "the discontinuities in Irish literary culture." Some collections have taken Deane's example to the extreme: for instance, The Ireland Anthology, edited by Sean Dunne, includes on its "literary map of Ireland" Edmund Spenser, William Thackeray, Katherine Mansfield, and John Betjeman, Chevalier de la Tocnaye, Alexis de Tocqueville, Friedrich En- gels, and Pope John Paul II. In The Oxford Book of Ireland editor Patricia Craig takes "the opposite extreme ..