Field Day Revisited (II): an Interview with Declan Kiberd1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aguisíní Appendices Aguisín 1: Comóradh Céad Bliain Ollscoil Na Héireann Appendix 1: Centenary of the National University of Ireland

Aguisíní Appendices Aguisín 1: Comóradh Céad Bliain Ollscoil na hÉireann Appendix 1: Centenary of the National University of Ireland Píosa reachtaíochta stairiúil ab ea Acht Ollscoileanna na hÉireann, 1908, a chuir deireadh go foirmeálta le tréimhse shuaite in oideachas tríú leibhéal na hEireann agus a d’oscail caibidil nua agus nuálaíoch: a bhunaigh dhá ollscoil ar leith – ceann amháin díobh i mBéal Feirste, in ionad sean-Choláiste na Ríona den Ollscoil Ríoga, agus an ceann eile lárnaithe i mBaile Átha Cliath, ollscoil fheidearálach ina raibh coláistí na hOllscoile Ríoga de Bhaile Átha Cliath, Corcaigh agus Gaillimh, athchumtha mar Chomh-Choláistí d’Ollscoil nua na hÉirean,. Sa bhliain 2008, rinne OÉ ceiliúradh ar chéad bliain ar an saol. Is iomaí athrú suntasach a a tharla thar na mblianta, go háiriithe nuair a ritheadh Acht na nOllscoileanna i 1997, a rinneadh na Comh-Choláistí i mBaile Átha Cliath, Corcaigh agus Gaillimh a athbhunú mar Chomh-Ollscoileanna, agus a rinneadh an Coláiste Aitheanta (Coláiste Phádraig, Má Nuad) a athstruchtúrú mar Ollscoil na hÉireann, Má Nuad – Comh-Ollscoil nua. Cuireadh tús le comóradh an chéid ar an 3 Nollaig 2007 agus chríochnaigh an ceiliúradh le mórchomhdháil agus bronnadh céime speisialta ar an 3 Nollaig 2008. Comóradh céad bliain ón gcéad chruinniú de Sheanad OÉ ar an lá céanna a nochtaíodh protráid den Seansailéirm, an Dr. Garret FitzGerald. Tá liosta de na hócáidí ar fad thíos. The Irish Universities Act 1908 was a historic piece of legislation, formally closing a turbulent chapter in Irish third level education and opening a new and innovational chapter: establishing two separate universities, one in Belfast, replacing the old Queen’s College of the Royal University, the other with its seat in Dublin, a federal university comprising the Royal University colleges of Dublin, Cork and Galway, re-structured as Constituent Colleges of the new National University of Ireland. -

AN INTRODUCTION to the ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE of COUNTY DONEGAL

AN INTRODUCTION TO THE ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE of COUNTY DONEGAL AN INTRODUCTION TO THE ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE of COUNTY DONEGAL COUNTY DONEGAL Mount Errigal viewed from Dunlewey. Foreword County Donegal has a rich architectural seventeenth-century Plantation of Ulster that heritage that covers a wide range of structures became a model of town planning throughout from country houses, churches and public the north of Ireland. Donegal’s legacy of buildings to vernacular houses and farm religious buildings is also of particular buildings. While impressive buildings are significance, which ranges from numerous readily appreciated for their architectural and early ecclesiastical sites, such as the important historical value, more modest structures are place of pilgrimage at Lough Derg, to the often overlooked and potentially lost without striking modern churches designed by Liam record. In the course of making the National McCormick. Inventory of Architectural Heritage (NIAH) The NIAH survey was carried out in phases survey of County Donegal, a large variety of between 2008 and 2011 and includes more building types has been identified and than 3,000 individual structures. The purpose recorded. In rural areas these include structures of the survey is to identify a representative as diverse as bridges, mills, thatched houses, selection of the architectural heritage of barns and outbuildings, gate piers and water Donegal, of which this Introduction highlights pumps; while in towns there are houses, only a small portion. The Inventory should not shopfronts and street furniture. be regarded as exhaustive and, over time, other A maritime county, Donegal also has a rich buildings and structures of merit may come to built heritage relating to the coast: piers, light. -

New Articulations of Irishness and Otherness’1 on the Contemporary Irish Stage

9780719075636_4_006.qxd 16/2/09 9:25 AM Page 98 6 ‘New articulations of Irishness and otherness’1 on the contemporary Irish stage Martine Pelletier Though the choice of 1990 as a watershed year demarcating ‘old’ Ireland from ‘new’, modern, Ireland may be a convenient simplification that ignores or plays down a slow, complex, ongoing process, it is nonethe- less true to say that in recent years Ireland has undergone something of a revolution. Economic success, the so-called ‘Celtic Tiger’ phe- nomenon, and its attendant socio-political consequences, has given the country a new confidence whilst challenging or eroding the old markers of Irish identity. The election of Mary Robinson as the first woman President of the Republic came to symbolise that rapid evolution in the cultural, social, political and economic spheres as Ireland went on to become arguably one of the most globalised nations in the world. As sociologist Gerard Delanty puts it, within a few years, ‘state formation has been diluted by Europeanization, diasporic emigration has been reversed with significant immigration and Catholicism has lost its capacity to define the horizons of the society’.2 The undeniable exhil- aration felt by many as Ireland set itself free from former constraints and limitations, waving goodbye to mass unemployment and emigra- tion, has nonetheless been counterpointed by a measure of anxiety. As the old familiar landscape, literal and symbolic, changed radically, some began to experience what Fintan O’Toole has described as ‘a process of estrangement [whereby] home has become as unfamiliar as abroad’.3 If Ireland changed, so did concepts of Irishness. -

Irish Divorce/Joyce's

Irish Divorce/Joyce’s Ulysses Irish Divorce/ Joyce’s Ulysses Peter Kuch Peter Kuch University of Otago Dunedin, New Zealand ISBN 978-1-349-95187-1 ISBN 978-1-137-57186-1 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-57186-1 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017939123 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2017 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. The publisher remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institu- tional affiliations. Printed on acid-free paper This Palgrave Macmillan imprint is published by Springer Nature The registered company is Nature America Inc. -

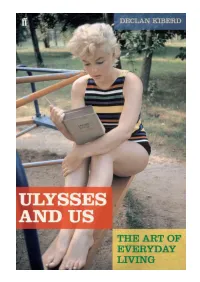

Ulysses and Us

Ulysses and Us The Art of Everyday Living declan kiberd First published in 2009 by Faber and Faber Ltd Bloomsbury House 74–77 Great Russell Street London wc1b 3da Typeset by Faber and Faber Ltd Printed in England by CPI Mackays, Chatham All rights reserved © Declan Kiberd, 2009 The right of Declan Kiberd to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library isbn 978–0–571–24254–2 2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1 In memory of John McGahern ‘Níl ann ach lá dár saol’ Contents Acknowledgements ix Note on the Text xi How Ulysses Didn’t Change Our Lives 3 How It Might Still Do So 16 Paralysis, Self-Help and Revival 32 1 Waking 41 10 Wandering 153 2 Learning 53 11 Singing 168 3 Thinking 64 12 Drinking 181 4 Walking 77 13 Ogling 193 5 Praying 89 14 Birthing 206 6 Dying 100 15 Dreaming 222 7 Reporting 113 16 Parenting 237 8 Eating 124 17 Teaching 248 9 Reading 137 18 Loving 260 Ordinary People’s Odysseys 277 Old Testaments and New 296 Depression and After: Dante’s Comedy 313 Shakespeare, Hamlet and Company 331 Conclusion: The Long Day Fades 347 Notes 359 Index 381 vii Acknowledgements For almost thirty years the students of University College Dublin have been teaching me about their famous fore- runner. -

The IRISH Seminar 2021

The IRISH Seminar 2021 Faculty Lead: Barry McCrea Format: Webinar* Please note that all times are listed in EST. Tuesday 8 June 9am Welcome & Introductions by Patrick Griffin & Barry McCrea 9.30am-10.30am Opening Roundtable: The State of Irish History Break Panel: Carole Holohan (Trinity College Dublin) 11.00am – 12.00pm Anne Dolan (Trinity College Dublin) Enda Delaney (University of Edinburgh) Ian McBride (Hertford College, Oxford) Moderator: Patrick Griffin (Notre Dame) 2-3pm Poetry Reading: Doireann Ní Gríofa Moderator: Brian Ó Conchubhair Wednesday 9 June Irish Studies from austerity to pandemic Editors of the Routledge International Handbook of Irish Studies (2021) in conversation with selected contributors. 9.00-9.15am Introduction with Renée Fox (University of California, Santa Cruz), Mike Cronin (Boston College) and Brian Ó Conchubhair (Notre Dame) 9.15-10.00am Eric Falci (University of California, Berkeley): Aesthetics of Irish poetry Sarah Townsend (University of New Mexico): Race in Ireland & Irish America. 10.00-10.15am Break 10.15-11.00am Claire Bracken (Union College): Gender and Irish Studies Nessa Cronin (NUI Galway): Environmentalities & the Anthropocene Maggie O'Neill (NUI Galway): The Ageing body in Irish Literature 11.00-11.15am Break 11.15-12.00pm Discussion and Q&A with panellists and participants Thursday 10 June Digital Humanities & Irish Studies 9.00-9.25 Beyond 2022 project overview. 9.25-10.00 Case Study 1: Medieval Ireland by Lynn Kigallon (Trinity College Dublin) 10.00-10.30 Break 10.30-11.00 Case Study 2: Eighteenth Century Ireland by Tim Murtagh (Trinity College Dublin) 11.00-11.15 Break 11.15-12.00 Discussion Friday 11 June Black Ireland Please note times for this seminar are subject to change** 9am Introduction by Chante Mouton Kinyon (Notre Dame) 9.15am Korey Garibaldi (Notre Dame) with Colm Toibin (Columbia): Culture and Racial Cosmopolitanism 10.15am Comfort break 10.45-11.45 Chante Mouton Kinyon with Colm Tóibín: Stranger in the Village 12:00-12.30 Discussion. -

Reporting on the Irish Question by the Times and Helsingin Sanomat 1910– 1919

Reporting on the Irish question by The Times and Helsingin Sanomat 1910– 1919 University of Oulu Department of History Master’s Thesis December 2017 Miika Tapaninen Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 3 1. The Road to Home rule 1910–1914 ................................................................................. 14 1.1. Helsingin Sanomat 1910–1914 ................................................................................. 15 1.1.1. Parliament Act: removing the road block .......................................................... 15 1.1.2. The necessity of Home Rule ............................................................................... 20 1.1.3. Ulster’s resistance: “Civil war or comedy”......................................................... 26 1.1.4. Mirroring the Irish and Finnish questions .......................................................... 30 1.2. The Times 1910–1914 ............................................................................................... 33 1.2.1. Parliament Act: constitutional crisis .................................................................. 34 1.2.2. The Home Rule Phantom: “unsubstantial and fugitive will-o-the-wisp” .......... 38 1.2.3. Justifying Ulster’s resistance .............................................................................. 43 2. The changing realities 1914–1919 .................................................................................. -

Irelands: Migration, Media, and Locality in Modern Day Dublin

Imagining Irelands: Migration, Media, and Locality in Modern Day Dublin by Aaron Christopher Thornburg Department of Cultural Anthropology Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Naomi Quinn, Supervisor ___________________________ Lee D. Baker ___________________________ Katherine P. Ewing ___________________________ John L. Jackson, Jr. ___________________________ Suzanne Shanahan Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Cultural Anthropology in the Graduate School of Duke University 2011 ABSTRACT Imagining Irelands: Migration, Media, and Locality in Modern Day Dublin by Aaron Christopher Thornburg Department of Cultural Anthropology Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Naomi Quinn, Supervisor ___________________________ Lee D. Baker ___________________________ Katherine P. Ewing ___________________________ John L. Jackson, Jr. ___________________________ Suzanne Shanahan An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Cultural Anthropology in the Graduate School of Duke University 2011 Copyright by Aaron Christopher Thornburg 2011 Abstract This dissertation explores the place of Irish-Gaelic language (Gaeilge) television and film media in the lives of youths living in the urban greater Dublin metropolitan area in the Republic of Ireland. By many accounts, there has been a Gaeilge renaissance underway in recent times. The number of Gaeilge-medium primary and secondary schools (Gaelscoileanna) has grown throughout the 1990s and into the twenty-first century, the year 2003 saw the passage of the Official Languages Act (laying the groundwork to assure all public services would be made available in Gaeilge as well as English), and as of January 2007 Gaeilge has become a working language of the European Union. -

74 Morris Joyce Cary

JOYCE CARY – LIBERAL TRAdiTIONS ‘Britain is profoundly a liberal state. Its dominating mind has been liberal for more than a century.’ These words were written by a novelist whose works Prisoner of Grace, Except the Lord, and Not Honour More explore the British liberal tradition against the backdrop of the great electoral landslide which gave the Liberal Party its overwhelming majority in 1906. Chester Nimmo, the main protagonist of this ‘political trilogy’, is a member of the resulting New Liberalism which took hold as a result. John Morris celebrates the work of the English novelist Joyce Cary, whose work is rooted in Liberal ideas. 16 Journal of Liberal History 74 Spring 2012 JOYCE CARY – LIBERAL TRAdiTIONS orn in Londonderry in The African Witch was made a Book and guide the soul – politics does 1888, Arthur Joyce Lunel Society choice, and he was finally the same thing for the body. God Cary was named after recognised as a fine novelist with is a character, a real and consistent his mother Charlotte the publication of Mister Johnson in being, or He is nothing. If God did Joyce in the Anglo-Irish 1939, which was also based on his a miracle He would deny His own Btradition of his class. Following the experiences in West Africa. nature and the universe would sim- Irish land reforms of the 1880s, the Though now largely forgot- ply blow up, vanish, become noth- family, now stripped of its lands, ten, Joyce Cary was the author of ing’. 4 Cary’s conviction instead was settled in London, where Charlotte many novels which were as highly that beauty and human love proved died of pneumonia in 1898 when regarded as those of his contempo- the existence ‘of some transcenden- Joyce was nine years old and his raries Graham Greene and Evelyn tal spiritual reality with which a brother Jack just six. -

In Joyce's Dubliners

PARALYSIS AS “SPIRITUAL LIBERATION” IN JOYCE’S DUBLINERS Iven Lucas Heister, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2014 APPROVED: David Holdeman, Major Professor and Chair of the Department of English Masood Raja, Committee Member Stephanie Hawkins, Committee Member Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Heister, Iven Lucas. Paralysis as “spiritual liberation” in Joyce’s Dubliners. Master of Arts (English), May 2014, 50 pp., references, 26 titles. In James Joyce criticism, and by implication Irish and modernist studies, the word paralysis has a very insular meaning. The word famously appears in the opening page of Dubliners, in “The Sisters,” which predated the collection’s 1914 publication by ten years, and in a letter to his publisher Grant Richards. The commonplace conception of the word is that it is a metaphor that emanates from the literal fact of the Reverend James Flynn’s physical condition the narrator recalls at the beginning of “The Sisters.” As a metaphor, paralysis has signified two immaterial, or spiritual, states: one individual or psychological and the other collective or social. The assumption is that as a collective and individual signifier, paralysis is the thing from which Ireland needs to be freed. Rather than relying on this received tradition of interpretation and assumptions about the term, I consider that paralysis is a two-sided term. I argue that paralysis is a problem and a solution and that sometimes what appears to be an escape from paralysis merely reinforces its negative manifestation. Paralysis cannot be avoided. Rather, it is something that should be engaged and used to redefine individual and social states. -

MORAL ELEMENTS in the NOVELS of JOYCE CARY Thesis Presented

1028 UNIVERSITY D'OTTAWA ~ ECOLE DES GRADUES MORAL ELEMENTS IN THE NOVELS OF JOYCE CARY Thesis presented to the Faculty of Arts of the University of Ottawa through the Department of English as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. UNIVERSITY OF OTTAWA - SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES UMI Number: DC53804 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI® UMI Microform DC53804 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 UNIVERSITE D'OTTAWA - ECOLE DES GRADUES ACKNOWLEDGMENT This thesis was prepared under the guidance of Dr- Emmett O'Grady of the University of Ottawa, Department of English. The writer would like to express his thanks to Dr. O'Grady for the interest he has shown in the thesis and for the suggestions he has made for its improvement. UNIVERSITY OF OTTAWA ~ SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES UNIVERSITE D'OTTAWA ~ ECOLE DES GRADUES CURRICULUM STUDIORUM William Ewing MacDonald Lindsay was born in Edinburgh, Scotland on March 19, 1915- He has been granted the following academic degrees: Bachelor of Arts (University of Toronto, 19^3); Master of Arts in English (St. -

6 X 10.5 Long Title.P65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-66686-2 - The Cambridge Companion to Brian Friel Edited by Anthony Roche Frontmatter More information The Cambridge Companion to Brian Friel Brian Friel is widely recognized as Ireland’s greatest living playwright, win- ning an international reputation through such acclaimed works as Transla- tions (1980) and Dancing at Lughnasa (1990). This collection of specially commissioned essays includes contributions from leading commentators on Friel’s work (including two fellow playwrights) and explores the entire range of his career from his 1964 breakthrough with Philadelphia, Here I Come! to his most recent success in Dublin and London with The Home Place (2005). The essays approach Friel’s plays both as literary texts and as performed drama, and provide the perfect introduction for students of both English and Theatre Studies, as well as theatregoers. The collection considers Friel’s lesser-known works alongside his more celebrated plays and provides a comprehensive crit- ical survey of his career. This is the most up-to-date study of Friel’s work to be published, and includes a chronology and further reading suggestions. anthony roche is Senior Lecturer in English and Drama at University College Dublin. He is the author of Contemporary Irish Drama: From Beckett to McGuinness (1994). © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-66686-2 - The Cambridge Companion to Brian Friel Edited by Anthony Roche Frontmatter More information THE CAMBRIDGE COMPANION TO BRIAN FRIEL