Business Law Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World Series Crossword (Answer

World Series Crossword Den Mothers 12345 P L A T E R O C K T O B E R J D I K R O 6789 10 D C B H U M I D O R I F D 11 12 I K A Z U O B C A O Y 13 14 R E D A Y W I L D C A R D 15 E D L E V I T R A E L T E 16 17 18 C O O R S F I E L D Z D C O E M T F I O G L B D I 19 20 V F K I N G T E A E L 21 H A F S R E 22 23 24 I T R O Y O I S H 25 26 27 28 M C M I I I L X X I I I I P I 29 30 N O I C Y Y O U N G 31 32 33 G N F O R D O R H 34 35 Y O R V I T R H W U P S 36 R N A V A R I T E K L T 37 38 O G A G N E K E A B T C E D 39 40 41 L A S I F M C M X C I I I 42 L E J O S H I U 43 44 45 F L O M A X B H E L T O N M T A L 46 S C H I L L I N G D D EclipseCrossword.com World Series Crossword Den Mothers 4. -

The 112Th World Series Chicago Cubs Vs. Cleveland Indians Saturday, October 29, 2016 Game 4 - 7:08 P.M

THE 112TH WORLD SERIES CHICAGO CUBS VS. CLEVELAND INDIANS SATURDAY, OCTOBER 29, 2016 GAME 4 - 7:08 P.M. (CT) FIRST PITCH WRIGLEY FIELD, CHICAGO, ILLINOIS 2016 WORLD SERIES RESULTS GAME (DATE RESULT WINNING PITCHER LOSING PITCHER SAVE ATTENDANCE Gm. 1 - Tues., Oct. 25th CLE 6, CHI 0 Kluber Lester — 38,091 Gm. 2 - Wed., Oct. 26th CHI 5, CLE 1 Arrieta Bauer — 38,172 Gm. 3 - Fri., Oct. 28th CLE 1, CHI 0 Miller Edwards Allen 41,703 2016 WORLD SERIES SCHEDULE GAME DAY/DATE SITE FIRST PITCH TV/RADIO 4 Saturday, October 29th Wrigley Field 8:08 p.m. ET/7:08 p.m. CT FOX/ESPN Radio 5 Sunday, October 30th Wrigley Field 8:15 p.m. ET/7:15 p.m. CT FOX/ESPN Radio Monday, October 31st OFF DAY 6* Tuesday, November 1st Progressive Field 8:08 p.m. ET/7:08 p.m. CT FOX/ESPN Radio 7* Wednesday, November 2nd Progressive Field 8:08 p.m. ET/7:08 p.m. CT FOX/ESPN Radio *If Necessary 2016 WORLD SERIES PROBABLE PITCHERS (Regular Season/Postseason) Game 4 at Chicago: John Lackey (11-8, 3.35/0-0, 5.63) vs. Corey Kluber (18-9, 3.14/3-1, 0.74) Game 5 at Chicago: Jon Lester (19-5, 2.44/2-1, 1.69) vs. Trevor Bauer (12-8, 4.26/0-1, 5.00) SERIES AT 2-1 CUBS AT 1-2 This is the 87th time in World Series history that the Fall Classic has • This is the eighth time that the Cubs trail a best-of-seven stood at 2-1 after three games, and it is the 13th time in the last 17 Postseason series, 2-1. -

Walpole Public Library DVD List A

Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] Last updated: 9/17/2021 INDEX Note: List does not reflect items lost or removed from collection A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z Nonfiction A A A place in the sun AAL Aaltra AAR Aardvark The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.1 vol.1 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.2 vol.2 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.3 vol.3 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.4 vol.4 ABE Aberdeen ABO About a boy ABO About Elly ABO About Schmidt ABO About time ABO Above the rim ABR Abraham Lincoln vampire hunter ABS Absolutely anything ABS Absolutely fabulous : the movie ACC Acceptable risk ACC Accepted ACC Accountant, The ACC SER. Accused : series 1 & 2 1 & 2 ACE Ace in the hole ACE Ace Ventura pet detective ACR Across the universe ACT Act of valor ACT Acts of vengeance ADA Adam's apples ADA Adams chronicles, The ADA Adam ADA Adam’s Rib ADA Adaptation ADA Ad Astra ADJ Adjustment Bureau, The *does not reflect missing materials or those being mended Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] ADM Admission ADO Adopt a highway ADR Adrift ADU Adult world ADV Adventure of Sherlock Holmes’ smarter brother, The ADV The adventures of Baron Munchausen ADV Adverse AEO Aeon Flux AFF SEAS.1 Affair, The : season 1 AFF SEAS.2 Affair, The : season 2 AFF SEAS.3 Affair, The : season 3 AFF SEAS.4 Affair, The : season 4 AFF SEAS.5 Affair, -

Ryan King-White Dissertation

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: BASEBALL, CITIZENSHIP, AND NATIONAL IDENTITY IN GEORGE W. BUSH’S AMERICA Ryan Edward King‐White, Doctor of Philosophy, 2008 Dissertation directed by: Professor David L. Andrews Department of Kinesiology The four separate, but related, studies within this research project seek to offer a critical understanding for how American national identit(ies), and particular forms of (cultural) citizenship are discursively constructed and performed in and through the sport of baseball. More specifically, this dissertation will utilize and expand upon critical theories of neoliberalism, citizenship, whiteness, and (physical) cultural studies to engage various empirical sites, which help provide the context for everyday life in contemporary America. Each chapter looks at various empirical aspects of the Little League World Series and the fans of the Boston Red Sox (popularly referred to as Red Sox Nation) that have historically privileged particular performances and behaviors often associated with white, American, heterosexual, upper‐middle class, masculine subject‐positions. In the first instance this project also attempts to describe how ‘normalized’ American citizenship is being (re)shaped in and through the sport of baseball. Secondly, I aim to critically evaluate claims made by both Little League Baseball, and the Boston Red Sox organization, in response to (popular) criticisms (Bryant, 20002; Mosher, 2001a, 2001b, 2001c) of regressive activity and behavior historically related to their organizations, that they -

LEVELAND INDIANS 2016 WORLD SERIES GAME TWO NOTES CLEVELAND INDIANS (1-0) Vs

OFFICIAL 2016 POSTSEASON INFORMATION LEVELAND INDIANS 2016 WORLD SERIES GAME TWO NOTES CLEVELAND INDIANS (1-0) vs. CHICAGO CUBS (0-1) RHP Trevor Bauer (0-0, 5.06) vs. RHP Jake Arrieta (0-1, 4.91) WS G2/Home #2 » Wednesday., Oct. 26, 2016 » Progressive Field » 7:08 p.m. ET » FOX, ESPN Radio, WTAM/WMMS/IRN TEAR THE ROOF OFF THE SUCKER | THE 112th WORLD SERIES FLASH LIGHT | CLEVELAND POSTSEASON HISTORY 2016 at a glance » The Cleveland Indians & Chicago Cubs are meeting in Major » Cleveland has gone 52-43 (.547) all-time in Postseason games, the League Baseball’s 112th World Series, the first meeting in Postseason 3rd-highest Postseason winning pct. of any A.L. team since 1901 vs. AL: Central West East history between the two franchises...Cleveland took a 1-0 series lead & 5th-highest by any team in the Majors behind Florida (.667, 22-11), 81-60 49-26 18-16 14-18 with Tuesday’s 6-0 shutout...second consecutive series for Cleveland New York-AL (.590, 223-155), New York-NL (.573, 51-38) & Baltimore vs. NL: Central West East to face an opponent for first time in PS history (also Toronto in ALCS); in (.551, 54-44)...record would be 53-43 if 1948 A.L. Pennant playoff game 13-7 4-0 0-0 9-7 In Series: Home Road Total ALDS, Tribe faced Boston for the sixth time in PS history. officially counted...Cleveland’s 95 official Postseason games are 6th- Overall 15-9-3 11-11-4 26-20-7 » The 2016 Fall Classic promises to be an historic event, as this year’s most played by any A.L. -

H 8015 State of Rhode Island

2012 -- H 8015 ======= LC02213 ======= STATE OF RHODE ISLAND IN GENERAL ASSEMBLY JANUARY SESSION, A.D. 2012 ____________ H O U S E R E S O L U T I O N COMMEMORATING THE 100TH ANNIVERSARY OF FENWAY PARK, HOME OF THE BOSTON RED SOX Introduced By: Representatives Kennedy, Fox, Mattiello, E Coderre, and Baldelli-Hunt Date Introduced: March 28, 2012 Referred To: House read and passed 1 WHEREAS, Historic Fenway Park, home of the Boston Red Sox and beloved by Red 2 Sox fans and baseball lovers throughout the world for its quaint intimacy, its world famous Green 3 Monster, and for the seamless fit between its architecture and the surrounding urban landscape, is 4 celebrating its 100 th anniversary in 2012. This celebration will be observed by the Boston Red 5 Sox, their millions of fans, and by traditional baseball and architecture lovers across the country 6 and globe; and 7 WHEREAS, Fenway Park opened in 1912 and is the oldest Major League Baseball Park 8 still in use. Built for the then-princely sum of $650,000, its asymmetrical design stemmed from 9 the need to position the park against the contours of the bustling and dense “Fenway-Kenmore” 10 neighborhood of Boston. Its architecture resulted in a small capacity for a major league baseball 11 park and its many endearing features, such as the short Pesky Pole down the right field line and 12 the “Triangle” in deep Center Field. Fenway Park’s lack of much foul territory brings the 13 spectators very close to the action and helps give it its reputation as a “hitters park,” because most 14 foul balls hit by a batter land in the stands, out of the grasp of the fielders, thus affording hitters 15 extra swings at the plate; and 16 WHEREAS, Fenway Park’s most prominent, famous, and beloved feature is the Green 17 Monster in the left field. -

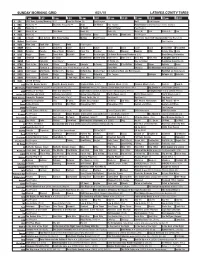

Sunday Morning Grid 6/21/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 6/21/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Golf Paid Program 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News On Money Paid Program Auto Racing Global RallyCross Series: Daytona. 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News (N) Paid Vista L.A. Paid 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Hour Mike Webb Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program 2015 U.S. Open Golf Championship Final Round. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Man Land Rock Star Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local RescueBot RescueBot 24 KVCR Painting Dowdle Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexican Cooking BBQ Simply Ming Lidia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Insight Ed Slott’s Retirement Roadmap (TVG) BrainChange-Perlmutter 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY7) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly A Knight’s Tale ›› 34 KMEX Paid Conexión Paid Program Al Punto (N) Tras la Verdad República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Fórmula 1 Fórmula 1 Gran Premio Austria 2015. -

Final 78-208.Indd

THE 2007 SEASON he Sun Devils made their 20th trip to the College IB Brett Wallace Padres. Matt Spencer was taken by the Philadelphia TWorld Series in Omaha, Nebraska in 2007, fi nishing Phillies in the third round, Andrew Romine went to the season with a 49-15 record…ASU swept the the Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim in the fi fth round, Tempe Regional and the Tempe Super Regional to Tim Smith was a 7th round pick of the Texas Rangers, secure their trip to Omaha, the fi rst time in school Brian Flores was selected in the 13th round by the history that Winkles Field-Packard Stadium at Brock Tampa Bay Devil Rays, Scott Mueller was taken by the Ballpark has hosted a Super Regional…Arizona State Baltimore Orioles in the 21st round, Josh Satow was won the 2007 Pac-10 championship with a record of a 28th round pick of the Seattle Mariners and Mike 19-5, tying for the most conference wins in history… Jones was picked in the 42nd round by the Chicago It was the seventh overall Pac-10 title and fi rst since White Sox…Joe Persichina and CJ Retherford each they shared it with UCLA and Stanford in 2000. It signed with the Chicago White Sox as free agents… was the fi rst outright title since 1993…ASU fi nished Brett Wallace and Petey Paramore were both named the season 35-3 at Winkles Field-Packard Stadium at to the USA Baseball National Team…Wallace was a Brock Ballpark, including 5-0 in postseason play… Semi-Finalist for the Golden Spikes Award, the Howser ASU fi nished the year ranked #5 in the nation Trophy and the Wallace Award…Five Devils earned and was ranked every week of 2007, never lower weekly awards from the Pac-10 during the course than 20th…2007 marked the 45th straight season of the season. -

The Chicago Cubs from 1945: History’S Automatic Out

Pace Intellectual Property, Sports & Entertainment Law Forum Volume 6 Issue 1 Spring 2016 Article 10 April 2016 The Chicago Cubs From 1945: History’s Automatic Out Harvey Gilmore Monroe College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/pipself Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Harvey Gilmore, The Chicago Cubs From 1945: History’s Automatic Out, 6 Pace. Intell. Prop. Sports & Ent. L.F. 225 (2016). Available at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/pipself/vol6/iss1/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at DigitalCommons@Pace. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pace Intellectual Property, Sports & Entertainment Law Forum by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Pace. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Chicago Cubs From 1945: History’s Automatic Out Abstract Since 1945, many teams have made it to the World Series and have won. The New York Yankees, Philadelphia/Oakland Athletics, and St. Louis Cardinals have won many. The Boston Red Sox, Chicago White Sox, and San Francisco Giants endured decades-long dry spells before they finally won the orldW Series. Even expansion teams like the New York Mets, Toronto Blue Jays, Kansas City Royals, and Florida Marlins have won multiple championships. Other expansion teams like the San Diego Padres and Texas Rangers have been to the Fall Classic multiple times, although they did not win. Then we have the Chicago Cubs. The Cubs have not been to a World Series since 1945, and have not won one since 1908. -

Congressional Record—Senate S7832

S7832 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE November 5, 2013 (2) recognizes the achievements of all the Whereas Mike Napoli blasted a game-decid- AUTHORITY FOR COMMITTEES TO crew, coaches, and staff who contributed to ing home run in game 3 of the American MEET the victory; and League Championship Series and produced (3) offers best wishes and support for the key hits and leadership for the Red Sox COMMITTEE ON BANKING, HOUSING, AND URBAN AFFAIRS team as it prepares to defend its title once throughout the World Series; again in American waters. Whereas Shane Victorino solidified his leg- Mr. MARKEY. Mr. President, I ask f end in postseason baseball lore by blasting a unanimous consent that the Com- mittee on Banking, Housing, and SENATE RESOLUTION 287—CON- grand slam that drove the Red Sox past the Detroit Tigers in game 6 of the American Urban Affairs be authorized to meet GRATULATING THE BOSTON RED League Championship Series, hitting a three during the session of the Senate on No- SOX ON WINNING THE 2013 run double in the World Series-clinching win vember 5, 2013, at 10 a.m., to conduct a WORLD SERIES at Fenway Park, and earning a Gold Glove hearing entitled ‘‘Housing Finance Re- Ms. WARREN (for herself, Mr. MAR- award for his stellar performance in right form: Protecting Small Lender Access KEY, Mr. REED, Mr. WHITEHOUSE, Mr. field; to the Secondary Mortgage Market.’’ MURPHY, Mr. LEAHY, Ms. AYOTTE, Mr. Whereas Dustin Pedroia, a sure-handed The PRESIDING OFFICER. Without fielder, was awarded the Gold Glove for his SANDERS, Mrs. -

By Michael Sandler

by Michael Sandler 1653_COVER.indd 1 4/29/08 8:22:59 AM [Intentionally Left Blank] 2007 WORLD SERIES by Michael Sandler Consultant: Jim Sherman Head Baseball Coach University of Delaware 1653_MikeLowell_FNL.indd 1 4/14/08 5:20:44 PM Credits Cover and Title Page, © Jaime Squire/Getty Images; 4, © Boston Globe/Stan Grossfeld/ Landov; 5, © Robert Caplin/Bloomberg News/Landov; 7, © David Bergman/Corbis; 8, © George Rizov; 9, Courtesy FIU Athletic Media Relations, Florida International University; 10, © Scott Halleran/Allsport/Getty Images; 12, © Barry Taylor/Ai Wire/ Newscom.com; 13, © Ezra Shaw/Getty Images; 14, © REUTERS/Shaun Best; 15, © Brad Mangin/MLB Photos via Getty Images; 16, © Brian Snyder/Reuters/Landov; 17, © Elsa/ Getty Images; 18, © Ron Vesely/MLB Photos via Getty Images; 19, © REUTERS/Mike Segar; 20, © Ron Vesely/MLB Photos via Getty Images; 21, © Paul Buck/epa/Corbis; 22T, © Elsa/Getty Images; 22C, © Elsa/Getty Images; 22B, © REUTERS/Ron Kuntz. Publisher: Kenn Goin Senior Editor: Lisa Wiseman Creative Director: Spencer Brinker Design: Stacey May Photo Researcher: James O’Connor Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Sandler, Michael, 1965- Mike Lowell and the Boston Red Sox : 2007 World Series / by Michael Sandler consultant, Jim Sherman. p. cm. — (World Series superstars) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-1-59716-739-0 (library binding) ISBN-10: 1-59716-739-8 (library binding) 1. Lowell, Mike—Juvenile literature. 2. Baseball players—United States— Biography—Juvenile literature. 3. Boston Red Sox (Baseball team) —Juvenile literature. 4. World Series (Baseball) (2007) —Juvenile literature. I. Sherman, Jim. II. Title. GV865.L69S36 2009 796.357092—dc22 [B] 2008001995 Copyright © 2009 Bearport Publishing Company, Inc. -

2007 NBC World Series Report

2007 NBC World Series Report INTRODUCTION This document contains the 2007 World Series Report, including Scorer’s Essay, the Tournament Brackets, line scores for each game, statistics for each team, trophy winners, the breakdown for tournament compensation and the media summaries. THE 73 RD ANNUAL NBC WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP TOURNAMENT The 2007 NBC World Series witnessed another first-time Champion, just as it did in 2006. The Havasu (AZ) Heat of the Pacific Southwest League won their first NBC title by defeating the Hays (KS) Larks in a 14-2 victory. Just as with the previous tournament, the Champion went undefeated with a 7-0 record. The Heat became the first team from Arizona to win the Championship. The Heat was an offensive juggernaut throughout the tournament, leading all teams with a .345 Batting Average and cranking out 11 Home Runs, more than doubling the previous team high of five. Havasu outscored its seven tournament opponents by a score of 71-20 with 40 of those runs coming in the first four innings of their games. The 2006 Champion and Runner-Up gave the Heat their closest games of the tournament. Havasu came from behind in the top of the ninth inning to defeat the Derby (KS) Twins by a score of 6-4 (12 innings); then the next night defeated the defending Champion, the Santa Barbara (CA) Foresters, by a score of 7-6. The Hays (KS) Larks played Havasu twice in the tournament and lost 11 - 7 (11 Innings) and 14 - 2 respectively. In the Championship Game, Hays shortstop Mike Brownstein hit a double down the right field line and was in scoring position with one out and advanced to third on a fielder’s choice.