CHAPTER THIRTY Anime's Situated Posthumanism: Representation, Mediality, Performance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Understanding the Emerging Danger of the Stand Alone Complex

Andrew DeMarco University Honors in Communications, Legal Institutions, Economics, and Government Capstone Advisor: Professor Andrea Tschemplik, CAS: Philosophy Standing Alone: Understanding the Emerging Danger of the Stand Alone Complex Japanese director and screenwriter, Kenji Kamiyama, has written works on the implications of the acceleration of technology, but it is in his most famous work, Ghost in the Shell: Stand Alone Complex, that he renders his most insightful and ominous theory about the changing nature of human society. Kamiyama proposes that in an increasingly interconnected society, the potential for individuals to act independently of one another, yet toward what may appear to others to be the same goal increases as well. Standalone individuals may be deceived into emulating the actions of an original actor for a perceived end when neither of these existbecoming “copycats without originals.” Kamiyama’s theory of the Stand Alone Complex is a valid one, and the danger it heralds needs to be addressed before the brunt of its effects are felt by those unable obtain remedy. What little literature exists on the theory is primarily concerned with medialogy, but the examination herein addresses the theoretical and philosophical grounding on which the theory stands. This study finds sufficient grounding for the theory through theoretical and philosophical discourse and historical case study. The practical and moral implications of the Stand Alone Complex are addressed through related frameworks, as Kant’s moral system provides a different perspective that informs legal discussions of intent. The implications for national governments are found highly dangerous, and further discourse on the theory is recommended, despite its “juvenile” origins. -

(Revised0507)JAPAN BOOTH 2013 Cannes FIX

CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Contents Introduction 1 Introduction Japan Booth is organized by JETRO/UNIJAPAN with the support from Agency for Cultural Affairs (Government of Japan). 2 Geneon Universal Entertainment Japan, LLC 3 Gold View Co., Ltd. 4 Happening Star Project JETRO, or the Japan External Trade Organization, is UNIJAPAN is a non-profit organization established 5 MODE FILMS INC. a government-related organization that works to pro- in 1957 by the Japanese film industry under the mote mutual trade and investment between Japan and auspice of the Government of Japan for the purpose 6 Nikkatsu Co. the rest of the world. of promoting Japanese cinema abroad. Initially named 7 Office Walker Inc. Originally established in 1958 to promote Japanese ex- ‘Association for the Diffusion of Japanese Film Abroad’ 8 Omgact Entertainment LLC ports abroad, JETRO’s core focus in the 21st century (UniJapan Film), in 2005 it joined hands with the has shifted toward promoting foreign direct investment organizer of Tokyo International Film Festival (TIFF), to 9 Open Sesame Co., Ltd. into Japan and helping small to medium-sized Japa- form a combined, new organization. 10 Production I.G nese firms maximize their global business potential. 11 SDP Inc. 12 Sedic International Inc. 13 Showgate Inc. 14 Tsuburaya Productions Co., Ltd. Category Action Drama Comedy Horror / Suspense Documentary Animation Screening schedule Day Starting Time Length of the Film Title Place 1 Geneon Universal Entertainment Japan, LLC Gold View Co., Ltd. The Chasing World: The Origin Belladonna Of Sadness AD 3000. 1 in 20 has the family name "SATO" in Japan. The A story about a young and beautiful woman, who has lived a life 150th king implements a horrific policy to reduce the number of of hardships. -

Japan Booth : Palais 01 - Booth 23.01 INTRODUCTION Japan Booth Is Organized by JETRO / UNIJAPAN with the Support from Agency for Cultural Affairs (Goverment of Japan)

JA P A N BOOTH 2 O 1 6 i n C A N N E S M a y 1 1 - 2 O, 2 O 1 6 Japan Booth : Palais 01 - Booth 23.01 INTRODUCTION Japan Booth is Organized by JETRO / UNIJAPAN with the support from Agency for Cultural Affairs (Goverment of Japan). JETRO, or the Japan External Trade Organization, is a government-related organization that works to promote mutual trade and investment between Japan and the rest of the world. Originally established in 1958 to promote Japanese exports abroad, JETRO’s core focus in the 21st century has shifted toward promoting foreign direct investment into Japan and helping small to medium-sized Japanese firms maximize their global business potential. UNIJAPAN is a non-profit organization established in 1957 by the Japanese film industry under the auspice of the Government of Japan for the purpose of promoting Japanese cinema abroad. Initially named “Association for the Diffusion of Japanese Film Abroad” (UniJapan Film), in 2005 it joined hands with the organizer of Tokyo International Film Festival (TIFF), to form a combined, new organization. CONTENTS 1 Asmik Ace, Inc. 2 augment5 Inc. 3 CREi Inc. 4 Digital Frontier, Inc. 5 Gold View Co., Ltd 6 Hakuhodo DY music & pictures Inc. (former SHOWGATE Inc.) 7 nondelaico 8 Open Sesame Co., Ltd. 9 POLYGONMAGIC Inc. 10 Production I.G 1 1 SDP, Inc. 12 STUDIO4˚C Co., Ltd. 13 STUDIO WAVE INC. 14 TOHOKUSHINSHA FILM CORPORATION 15 Tokyo New Cinema, Inc. 16 TSUBURAYA PRODUCTIONS CO., LTD. 17 Village INC. CATEGORY …Action …Drama …Comedy …Horror / Suspense …Documentary …Animation …Other SCREENING SCHEDULE Title Day / Starting Time / Length of the Film / Place Asmik Ace, Inc. -

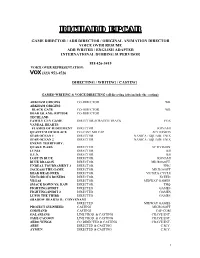

Richard Epcar Voice Over Resume

RICHARD EPCAR VOICE OVER RESUME ADR DIRECTOR / ORIGINAL ANIMATION DIRECTOR / GAME DIRECTOR ADR WRITER / ENGLISH ADAPTER INTERNATIONAL DUBBING SUPERVISOR 818 426-3415 VOICE OVER REPRESENTATION: (323) 939-0251 VOICE ACTING RESUME GAME VOICE ACTING ARKHAM ORIGINS SEVERAL CHARACTERS WB INJUSTICE: GODS AMONG US THE JOKER WB INFINITE CRISIS THE JOKER WB MORTAL KOMBAT X RAIDEN WARNER BROS. FINAL FANTASY XIV 2.4-2.5 ILBERD ACE COMBAT ASSAULT HORIZON LEGACY STARGATE SG-1: UNLEASHED GEN. GEORGE HAMMOND MGM SAINTS ROW 4 LEAD VOICE (CYRUS TEMPLE) VOICEWORKS PRODS MARVEL HEROS SEVERAL VOICES MARVEL THE BUREAU: XCOM DECLASSIFIED LEAD VOICE TAKE 2 PRODS. BLADE STORM NIGHTMARE NARRATOR ULTIMATE NINJA STORM 3 LEAD VOICE NARUTO VG LEAD VOICE STUDIPOLIS CALL OF DUTY- BLACK OPS II SEVERAL VOICES EA RESIDENT EVIL 6 MO-CAPPED THE PRESIDENT ACTIVISION SKYRIM- THE ELDER SCROLLS V LEAD VOICES BETHESDA (BEST GAME OF THE YEAR 2011-Spike Video Awards) KINGDOM HEARTS: DREAM DROP DISTANCE LEAD VOICE SQUARE ENIX / DISNEY FINAL FANTASY XIV LEAD VOICE (GAIUS VAN BAELSAR) SQUARE ENIX MAD MAX SEVERAL VOICES DEAD OR ALIVE 5 LEAD VOICE VINDICTUS LEAD VOICE TIL MORNING’S LIGHT LEAD VOICE WAY FORWARD POWER RANGERS MEGAFORCE LEAD VOICES BANG ZOOM FINAL FANTASY XIII.3 LEAD VOICE GUILTY GEARS X-RD LEAD VOICE SQUARE ENIX YOGA Wii LEAD VOICE GORMITI LEAD VOICE EARTH DEFENSE FORCE LEAD VOICE 1 ATELIER AYESHA LEAD VOICE BANG ZOOM X-COM: ENEMY UNKNOWN LEAD VOICE TAKE 2 PRODS. OVERSTRIKE LEAD VOICE INSOMNIAC GAMES DEMON’S SCORE LEAD VOICES CALL OF DUTY BLACK OPS LEAD VOICES EA TRANSFORMERS -

Protoculture Addicts Is ©1987-2003 by Protoculture

Sample file CONTENTS 3 ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ P r o t o c u l t u r e A d d i c t s # 7 9 November / December 2003. Published bimonthly by Protoculture, P.O. Box 1433, Station B, Montreal, Qc, ANIME VOICES Canada, H3B 3L2. Web: http://www.protoculture-mag.com Presentation ............................................................................................................................ 3 Letters ................................................................................................................................... 70 E d i t o r i a l S t a f f Claude J. Pelletier [CJP] – Publisher / Editor-in-chief [email protected] NEWS Miyako Matsuda [MM] – Editor / Translator ANIME & MANGA NEWS: Japan ................................................................................................. 5 Martin Ouellette [MO] – Editor ANIME RELEASES (VHS / R1 DVD) .............................................................................................. 6 PRODUCTS RELEASES (Live-Action, Soundtracks) ......................................................................... 7 C o n t r i b u t i n g E d i t o r s MANGA RELEASES .................................................................................................................... 8 Keith Dawe, Kevin Lillard, James S. Taylor MANGA SELECTION .................................................................................................................. 8 P r o d u c t i o n A s s i s t a n t s ANIME & MANGA NEWS: North America ................................................................................... -

Mamoru Oshii Filmography

MAMORU OSHII FILMOGRAPHY Information about the projects in which Mamoru Oshii has been involved is given in the following order: English title; Japanese title (if different); release date (format); Oshii’s role in the project. In compiling this list, I am indebted to Makoto Noda’s book My Dear, Ma- moru Oshii (Zenryaku Oshii Mamoru-sama) and his website at http://www.ops.dti. ne.jp/~makoto99/hakobune/nenpyou/ Time Bokan Series: Yattaman Taimu bokan shiriizu: Yattaaman January 1977–January 1979 (108 TV episodes) Chief assistant director (second half), storyboards (2 episodes) One-Hit Kanta Ippatsu Kanta-kun September 1977–September 1978 (53 TV episodes) Storyboards (4 episodes), technical director (2 episodes) Magical Girl Tickle Majokko Chikkuru March 1978–January 1979 (45 TV episodes) Storyboards (1 episode) Science Ninja Team Gatchaman II Kagaku ninjatai Gatchaman II October 1978–September 1979 (52 TV episodes) Storyboards (3 episodes), technical director (3 episodes) Time Bokan Series: Zendaman Taimu bokan shiriizu: Zendaman February 1979–January 1980 (52 TV episodes) Storyboards (10 episodes), technical director (9 episodes), storyboard revisions (1 episode) Nils’s Mysterious Journey Nirusu no fushigina tabi 264 * MAMORU OSHII FILMOGRAPHY January 1980–March 1981 (52 TV episodes) Storyboards (11 episodes), technical director (18 episodes) Time Bokan Series: Time Patrol Team Otasukeman Taimu bokan shiriizu: taimu patorourutai Otasukeman February 1980–January 1981 (53 TV episodes) Storyboards (6 episodes) Time Bokan Series: Yattodetaman -

Please Click HERE to Download My Voice Directing

RICHARD EPCAR GAME DIRECTOR / ADR DIRECTOR / ORIGINAL ANIMATION DIRECTOR VOICE OVER RESUME ADR WRITER / ENGLISH ADAPTER INTERNATIONAL DUBBING SUPERVISOR 818 426-3415 VOICE OVER REPRESENTATION: (323) 951-4526 DIRECTING / WRITING / CASTING GAMES–WRITING & VOICE DIRECTING (all directing jobs include the casting) ARKHAM ORIGINS CO-DIRECTOR WB ARKHAM ORIGINS: BLACK GATE CO-DIRECTOR WB DEAD ISLAND: RIPTIDE CO-DIRECTOR TECHLAND FAMILY GUY GAME DIRECTOR-SCRATCH TRACK FOX VANDAL HEARTS: FLAMES OF JUDGEMENT DIRECTOR KONAMI QUANTUM OF SOLACE CO-CAST MO CAP ACTIVISION STAR OCEAN 1 DIRECTOR NANICA / SQUARE ENIX STAR OCEAN 2 DIRECTOR NANICA / SQUARE ENIX ENEMY TERRITORY: QUAKE WARS DIRECTER ACTIVISION LUNIA DIRECTOR IJJI S.U.N. DIRECTOR IJJI LOST IN BLUE DIRECTOR KONAMI BLUE DRAGON DIRECTOR MICROSOFT UNREAL TOURNAMENT 3 DIRECTOR EPIC JACKASS THE GAME DIRECTOR MICROSOFT DEAD HEAD FRED DIRECTOR VICIOUS CYCLE VICTORIOUS BOXERS DIRECTOR XCEED VEGAS DIRECTOR MIDWAY GAMES SMACK DOWN VS. RAW DIRECTOR THQ FIGHTING SPIRIT DIRECTED GAMES FIGHTING SPIRIT 2 DIRECTED GAMES LUPIN THE THIRD DIRECTED GAMES SHADOW HEARTS II: CONVENANT DIRECTED MIDWAY GAMES PROJECT SYLPHEED CASTING MICROSOFT GODHAND CASTING CAP-COM GALARIANS LINE PROD. & CASTING CRAVE ENT. JADE CACOON LINE PROD. & CASTING CRAVE ENT. AERO WINGS CO-DIRECTED & CASTING CRAVE ENT. ABBY DIRECTED & CASTING C.M.Y. AYMUN DIRECTED & CASTING C.M.Y. 1 ANIMATED CARTOONS – FEATURES AND TELEVISION-WRITING & DIRECTING KICK-HEART CAST/WROTE & DIRECTED PROD I-G ALMOST HEROES ADR DIRECTOR DIGIART JUNGLE SHUFFLE ADR DIRECTOR SPACE DOGS 3-D CAST/WROTE & DIRECTED EPIC BLUE ELEPHANT CAST/CO-DIRECTED WEINSTEIN CO. GHOST IN THE SHELL 2- INNOCENCE WROTE & DIRECTED-FEATURE MANGA U.K. -

May 17Th to 26Th, 2017

JAPAN BOOTH 2017 IN CANNES May 17th to 26th, 2017 Japan Booth : Palais 01-23.01 Contents Introduction 2 1 ARTicle FILMS 2 augment5 Inc. 3 3 BLAST INC. 4 CREi Inc. UNIJAPAN is a non-profit organization established 4 5 Free Stone Productions Co., Ltd. JETRO, or the Japan External Trade Organization, is a government-related organization that works to promote in 1957 by the Japanese film industry under the 6 Gold View Co., Ltd. mutual trade and investment between Japan and the rest auspice of the Government of Japan for the purpose 5 7 NEGA Co. of the world. of promoting Japanese cinema abroad. Initially named 8 Open Sesame Co., Ltd. Originally established in 1958 to promote Japanese ‘Association for the Diffusion of Japanese Film Abroad’ 6 9 Production I.G exports abroad, JETRO’s core focus in the 21st century (UniJapan Film), in 2005 it joined hands with the has shifted toward promoting foreign direct investment into organizer of Tokyo International Film Festival (TIFF), to 10 SDP, Inc. Japan and helping small to medium-sized Japanese firms form a combined, new organization. 7 1 1 STUDIO4℃ Co., Ltd. maximize their global business potential. 1 2 TOHOKUSHINSHA FILM CORPORATION 8 13 Village INC. SCREENING SCHEDULE Category Contents Introduction 2 1 ARTicle FILMS 2 augment5 Inc. 3 3 BLAST INC. 4 CREi Inc. UNIJAPAN is a non-profit organization established 4 5 Free Stone Productions Co., Ltd. JETRO, or the Japan External Trade Organization, is a government-related organization that works to promote in 1957 by the Japanese film industry under the 6 Gold View Co., Ltd. -

October 2K2 Issue.Qxd

Building on a Masterpiece Director Kenji Kamiyama and scriptwriter Yoshiki Sakurai talk to Penumbric about work on Production I.G.’s new TV series Stand Alone Complex, the latest addition to Masamune Shirow’s classic cyberpunk story Ghost in the Shell he near future. Completely cybernetic bodies are not only possible, but encountered regularly—albeit some Tare nonhuman machines, while others are at least nom- inally human. In fact, some persons’ only human parts are their brains, and even those are not wholly human. Meet Major Motoko Kusanagi, a special agent for the govern- ment. She is one of these almost entirely cybernetic humans, as are most of the members of her team. Her assignment: To expose/arrest/destroy cyborg criminals and “ghost” hackers, and to come back alive afterwards. But there’s more to it than that. In the Ghost in the Shell series by Masamune Shirow, cyber- punk meets cybernautica as people are fully integrated into the electronic environment which surrounds them and permeates their daily lives. Are you a slow typer? Try having fingers that split into fifty smaller and more mobile digits. Having trouble GitS:SAC continued next page PICTURED: Images from Production I.G.’s Ghost in the Shell: Stand Alone Complex. Click for larger image. Oct 2k2 psfm • 3 What’s this “anime” & “manga” continued from GitS:SAC previous page we keep talking about? with your computer? Jack into it directly via We reckon there are very few of you out there a port in your neck and give it a piece of your who haven’t heard of anime by now, although mind. -

Download October2k2

Table of contents from the editor interview interview with Ghost in the Shell: Stand Alone Complex Director Kenji Kamiyama Scriptwriter Yoshiki Sakurai fiction by Anita Harkess The Student’s Nightmare by Leslie Aguillard Bill and the Night by Peri Charlifu Seeds art courtesy Production I.G. GitS: SAC by Michael Connolly Dragon by Leslie Aguillard Bill and the Night by Peri Charlifu Cthulhu graphic narrative by Stan Yan Misclassified Romance by Brian Comber Hector by Robert Elrod Life contributors’ bios on the cover: Stand Alone Complex images courtesy Production I.G. Oct 2k2 psfm • 1 It’s a happy, creepy time of year by Jeff Georgeson his is my favorite time of year. It is a time of beginnings: the Another reason I like this time of year is, of course, Halloween, the oppressive heat of summer has subsided, and the cool crisp- time when traditionally the doors to the spirit world were opened. To Tness of fall has begun; the boredom of summer break done, celebrate, we have some macabre offerings for you. The intellectual- school started (and I one of those who actually liked being in school); ly creepy (or is that intellectual and creepy?) renderings of Robert the sports I enjoy (football and hockey) are into their seasons; Elrod grace our page for the first time, with his graphic narrative Hollywood gears up for the holiday season rush of Big Films; and “Life”; “Hector” (another gn), this time by Brian Comber, is a vision even television begins anew, with new shows just testing the waters of out of Poe; and even Stan Yan’s “Misclassified Romance” answers the audience delight. -

LANDA-DISSERTATION-2017.Pdf (4.978Mb)

The Dissertation Committee for Amanda Landa certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Contemporary Japanese Seishun Eiga Cinema Committee: Lalitha Gopalan, Supervisor Janet Staiger, Co-Supervisor Kirsten Cather Shanti Kumar David Desser Michael Kackman Contemporary Japanese Seishun Eiga Cinema by Amanda Landa Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the GraduateSchool of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2017 Acknowledgements The dissertation process is always present and foreboding in one’s graduate career. An always looming presence, the first chapter is always theoretically sketched, perhaps even drafted, but the rest are generally to be filed under “fiction.” The same, of course, happened for me, and throughout this endeavor I have learned to draft, to re-read and edit, and most especially to never be afraid to start over. My primary goal was to hone my writerly voice, to elevate from description into argument and most of all, to slow down. Time and financial pressures are plentiful, and early in the writing process I wanted to rush; to achieve quickly what was later revealed to me something that could not and should not be rushed. I chose to write chapter by chapter as the films and genre categories presented themselves, allowing myself to enjoy each chapter’s research process in small achievable steps. Integral to this process are my co-supervisors, Associate Professor Lalitha Gopalan and Professor Emeritus Janet Staiger. In particular, I want to give thanks for Lalitha’s rigorous mentorship, guidance, and enthusiasm for this project and its films and Janet, a constant mentor, whose patience and attendance to both my writerly and emotional well- being will never be forgotten. -

Le 12 Juillet Au Cinéma

LE 12 JUILLET AU CINÉMA Kenji KAMIYAMA, réalisateur de Eden of the East, principal est une jeune lycéenne, ordinaire de Kokone Morikawa vit avec son père dans la préfecture d’Okayama. Moribito: Guardian of the Spirit et Ghost in the prime abord, si ce n’est qu’elle peut s’endormir C’est une lycéenne ordinaire, sans talent spécial si ce n’est celui- Shell: Stand Alone Complex, revient avec un n’importe où et n’importe quand. Une série de ci : elle peut s’endormir n’importe quand et n’importe où. Depuis film sur le passage à l’âge adulte qui mélange le rêves étranges la taraude depuis peu. Quand quelques temps, elle fait des rêves étranges. Son père, Momotarô, monde des rêves et le suspense. le monde réel commence à changer de façon est un homme bourru qui passe la majeure partie de son temps étrange, elle comprend que la réponse se trouve dans son garage à réparer et à modifier des voitures. Pourquoi rêvons-nous ? Les rêves peuvent révéler dans ses rêves. Elle se rend à Tokyo pour résoudre nos angoisses secrètes et les remous de notre ce mystère, et en chemin fait une découverte On est en 2020, trois jours avant l’ouverture des Jeux Olympiques cœur. Leur but réel est peut-être de nous montrer encore plus grande sur ses origines. de Tokyo. Sans avertissement préalable, Momotarô est arrêté et ce qui nous manque. Le réalisateur Kenji KAMIYAMA conduit à Tokyo pour être interrogé. Bien que son père soit un les a choisis comme motif pour son dernier Hirune Hime - Rêves éveillés est un road- peu marginal, Kokone ne peut croire en sa culpabilité.