Schenker's Versus Schenkerian Attitudes Towards Sequences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Advanced Schenkerian Analysis: Perspectives on Phrase Rhythm, Motive, and Form by David Beach

Advanced Schenkerian Analysis: Perspectives on Phrase Rhythm, Motive, and Form by David Beach. New York and London: Routledge, 2012.1 Review by David Carson Berry After Allen Forte’s and Steven Gilbert’s Introduction to Schenkerian Analysis was published in 1982, it effectively had the textbook market to itself for a decade (a much older book by Felix Salzer and a new translation of one by Oswald Jonas not withstanding).2 A relatively compact Guide to Schenkerian Analysis, by David Neumeyer and Susan Tepping, was issued in 1992;3 and in 1998 came Allen Cadwallader and David Gagné’s Analysis of Tonal Music: A Schenkerian Approach, which is today (in its third edition) the dominant text.4 Despite its ascendance, and the firm legacy of the Forte/Gilbert book, authors continue to crowd what is a comparatively small market within music studies. Steven Porter offered the interesting but dubiously named Schenker Made Simple in 1 Advanced Schenkerian Analysis: Perspectives on Phrase Rhythm, Motive, and Form, by David Beach. New York and London: Routledge, 2012; hardback, $150 (978-0- 415-89214-8), paperback, $68.95 (978-0-415-89215-5); xx, 310 pp. 2 Allen Forte and Steven E. Gilbert, Introduction to Schenkerian Analysis (New York: Norton, 1982). Felix Salzer’s book (Structural Hearing: Tonal Coherence in Music [New York: Charles Boni, 1952]), though popular in its time, was viewed askance by orthodox Schenkerians due to its alterations of core tenets, and it was growing increasingly out of favor with mainstream theorists by the 1980s (as evidenced by the well-known rebuttal of its techniques in Joseph N. -

Computational Methods for Tonality-Based Style Analysis of Classical Music Audio Recordings

Fakult¨at fur¨ Elektrotechnik und Informationstechnik Computational Methods for Tonality-Based Style Analysis of Classical Music Audio Recordings Christof Weiß geboren am 16.07.1986 in Regensburg Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doktoringenieur (Dr.-Ing.) Angefertigt im: Fachgebiet Elektronische Medientechnik Institut fur¨ Medientechnik Fakult¨at fur¨ Elektrotechnik und Informationstechnik Gutachter: Prof. Dr.-Ing. Dr. rer. nat. h. c. mult. Karlheinz Brandenburg Prof. Dr. rer. nat. Meinard Muller¨ Prof. Dr. phil. Wolfgang Auhagen Tag der Einreichung: 25.11.2016 Tag der wissenschaftlichen Aussprache: 03.04.2017 urn:nbn:de:gbv:ilm1-2017000293 iii Acknowledgements This thesis could not exist without the help of many people. I am very grateful to everybody who supported me during the work on my PhD. First of all, I want to thank Prof. Karlheinz Brandenburg for supervising my thesis but also, for the opportunity to work within a great team and a nice working enviroment at Fraunhofer IDMT in Ilmenau. I also want to mention my colleagues of the Metadata department for having such a friendly atmosphere including motivating scientific discussions, musical activity, and more. In particular, I want to thank all members of the Semantic Music Technologies group for the nice group climate and for helping with many things in research and beyond. Especially|thank you Alex, Ronny, Christian, Uwe, Estefan´ıa, Patrick, Daniel, Ania, Christian, Anna, Sascha, and Jakob for not only having a prolific working time in Ilmenau but also making friends there. Furthermore, I want to thank several students at TU Ilmenau who worked with me on my topic. Special thanks go to Prof. -

Schenkerian Analysis in the Modern Context of the Musical Analysis

Mathematics and Computers in Biology, Business and Acoustics THE SCHENKERIAN ANALYSIS IN THE MODERN CONTEXT OF THE MUSICAL ANALYSIS ANCA PREDA, PETRUTA-MARIA COROIU Faculty of Music Transilvania University of Brasov 9 Eroilor Blvd ROMANIA [email protected], [email protected] Abstract: - Music analysis represents the most useful way of exploration and innovation of musical interpretations. Performers who use music analysis efficiently will find it a valuable method for finding the kind of musical richness they desire in their interpretations. The use of Schenkerian analysis in performance offers a rational basis and an unique way of interpreting music in performance. Key-Words: - Schenkerian analysis, structural hearing, prolongation, progression,modernity. 1 Introduction Even in a simple piece of piano music, the ear Musical analysis is a musicological approach in hears a vast number of notes, many of them played order to determine the structural components of a simultaneously. The situation is similar to that found musical text, the technical development of the in language. Although music is quite different to discourse, the morphological descriptions and the spoken language, most listeners will still group the understanding of the meaning of the work. Analysis different sounds they hear into motifs, phrases and has complete autonomy in the context of the even longer sections. musicological disciplines as the music philosophy, Schenker was not afraid to criticize what he saw the musical aesthetics, the compositional technique, as a general lack of theoretical and practical the music history and the musical criticism. understanding amongst musicians. As a dedicated performer, composer, teacher and editor of music himself, he believed that the professional practice of 2 Problem Formulation all these activities suffered from serious misunderstandings of how tonal music works. -

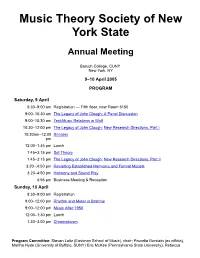

Program and Abstracts for 2005 Meeting

Music Theory Society of New York State Annual Meeting Baruch College, CUNY New York, NY 9–10 April 2005 PROGRAM Saturday, 9 April 8:30–9:00 am Registration — Fifth floor, near Room 5150 9:00–10:30 am The Legacy of John Clough: A Panel Discussion 9:00–10:30 am TextMusic Relations in Wolf 10:30–12:00 pm The Legacy of John Clough: New Research Directions, Part I 10:30am–12:00 Scriabin pm 12:00–1:45 pm Lunch 1:45–3:15 pm Set Theory 1:45–3:15 pm The Legacy of John Clough: New Research Directions, Part II 3:20–;4:50 pm Revisiting Established Harmonic and Formal Models 3:20–4:50 pm Harmony and Sound Play 4:55 pm Business Meeting & Reception Sunday, 10 April 8:30–9:00 am Registration 9:00–12:00 pm Rhythm and Meter in Brahms 9:00–12:00 pm Music After 1950 12:00–1:30 pm Lunch 1:30–3:00 pm Chromaticism Program Committee: Steven Laitz (Eastman School of Music), chair; Poundie Burstein (ex officio), Martha Hyde (University of Buffalo, SUNY) Eric McKee (Pennsylvania State University); Rebecca Jemian (Ithaca College), and Alexandra Vojcic (Juilliard). MTSNYS Home Page | Conference Information Saturday, 9:00–10:30 am The Legacy of John Clough: A Panel Discussion Chair: Norman Carey (Eastman School of Music) Jack Douthett (University at Buffalo, SUNY) Nora Engebretsen (Bowling Green State University) Jonathan Kochavi (Swarthmore, PA) Norman Carey (Eastman School of Music) John Clough was a pioneer in the field of scale theory. -

Analyzing Fugue: a Schenkerian Approach by William Renwick

Analyzing Fugue: A Schenkerian Approach by William Renwick. Harmonologia Series No. 8 (edited by Joel Lester). Stuyvesant, New York: Pendragon Press, 1995. Review by Robert Gauldin In recent years focus has tended to shift from Heinrich Schenker's canonical principles of hierarchical voice leading to his comments on musical form, as formulated in the final section of Der freie Satz.1 While Schenker's middleground and background levels are eminently suited for revealing the tonal structure of such designs as ternary and sonata, their application to other formal genres raises certain questions.2 Aside from his essay on organicism in the fugue, which deals with the C Minor fugue in WTC I, Schenker rarely ventured into contrapuntal genres.3 In fact, only a handful of fugal analyses exist in subsequent Schenkerian literature.4 It is ^See his Free Composition. 2 vols. Translated and edited by Ernst Oster. (New York: Longman, 1979), 1:128-45. ^In this regard, Joel Garland and Charles Smith have recently explored spe- cific aspects of rondo and variation form, respectively. See Garland's "Form, Genre, and Style in the Eighteenth-Century Rondo," Music Theory Spectrum 17/1 (Spring 1995), 27-52, and Smith's "Head-Tones, Mediants, Reprises: A Formal Narrative of Brahms' Handel Variations," paper deliv- ered at the Eastman School of Music, March 1995. In the latter, interest centers around^ Variation 21, where the original Urlinie 3-2-1 in Bb major is now set as 5-4-3 in the relative minor key. A similar problem of Urlinie reinterpretation occurs in Brahms' Haydn Variations Op. -

The Piano Improvisations of Chick Corea: an Analytical Study

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1996 The iP ano Improvisations of Chick Corea: An Analytical Study. Daniel Alan Duke Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Duke, Daniel Alan, "The iP ano Improvisations of Chick Corea: An Analytical Study." (1996). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 6334. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/6334 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the te d directly fi-om the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

The University of Chicago an Experience-Oriented

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO AN EXPERIENCE-ORIENTED APPROACH TO ANALYZING STRAVINSKY’S NEOCLASSICISM A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC BY SARAH MARIE IKER CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2017 CONTENTS List of Figures ...................................................................................................................................... iv List of Tables ..................................................................................................................................... viii Acknowledgments ............................................................................................................................... ix Abstract .................................................................................................................................................. x Introduction: Analysis, Experience, and Experience-Oriented Analysis ..................................... 1 1 Neoclassicism, Analysis, and Experience ................................................................................ 10 1.1 Neoclassicism After the Great War ................................................................................. 10 1.2 Analyzing Neoclassicism: Problems and Solutions ....................................................... 18 1.3 Whence Listener Experience? ........................................................................................... 37 1.4 The Problem of Historicism ............................................................................................ -

A Schenkerian Analysis of Ravel's Introduction And

Schenkerian Analysis of Ravel A SCHENKERIAN ANALYSIS OF RAVEL’S INTRODUCTION AND ALLEGRO FROM THE BONNY METHOD OF GUIDED IMAGERY AND MUSIC Robert Gross, MM, MA, DMA ABSTRACT This study gathers image and emotional responses reported by Bruscia et al. (2005) to Ravel’s Introduction and Allegro, which is a work included for use in the Bonny Method of Guided Imagery and Music (BMGIM). A Schenkerian background of the Ravel is created using the emotional and image responses reported by Bruscia’s team. This background is then developed further into a full middleground Schenkerian analysis of the Ravel, which is then annotated. Each annotation observes some mechanical phenomenon which is then correlated to one or more of the responses given by Bruscia’s team. The argument is made that Schenkerian analysis can inform clinicians about the potency of the pieces they use in BMGIM, and can explain seemingly contradictory or incongruous responses given by clients who experience BMGIM. The study includes a primer on the basics of Schenkerian analysis and a discussion of implications for clinical practice. INTRODUCTION For years I had been fascinated by musical analysis. My interest began in a graduate-level class at Rice University in 1998 taught by Dr. Richard Lavenda, who, regarding our final project, had the imagination to say that we could use an analytical method of our devising. I invented a very naïve method of performing Schenkerian analysis on post-tonal music; the concept of post-tonal prolongation and the application of Schenkerian principles to post-tonal music became a preoccupation that has persisted for me to this day. -

Concept of Tonality"

Gamut: Online Journal of the Music Theory Society of the Mid-Atlantic Volume 7 Issue 1 Article 7 May 2014 The Early Schenkerians and the "Concept of Tonality" John Koslovsky Conservatorium van Amsterdam; Utrecht University Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/gamut Part of the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation Koslovsky, John (2014) "The Early Schenkerians and the "Concept of Tonality"," Gamut: Online Journal of the Music Theory Society of the Mid-Atlantic: Vol. 7 : Iss. 1 , Article 7. Available at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/gamut/vol7/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Volunteer, Open Access, Library Journals (VOL Journals), published in partnership with The University of Tennessee (UT) University Libraries. This article has been accepted for inclusion in Gamut: Online Journal of the Music Theory Society of the Mid-Atlantic by an authorized editor. For more information, please visit https://trace.tennessee.edu/gamut. THE EARLY SCHENKERIANS AND THE “CONCEPT OF TONALITY” JOHN KOSLOVSKY oday it would hardly raise an eyebrow to hear the words “tonality” and T “Heinrich Schenker” uttered in the same breath, nor would it startle anyone to think of Schenker’s theory as an explanation of “tonal music,” however broadly or narrowly construed. Just about any article or book dealing with Schenkerian theory takes the terms “tonal” or “tonality” as intrinsic to the theory’s purview of study, if not in title then in spirit.1 Even a more general book such as The Cambridge History of Western Music Theory seems to adopt this position, and has done so by giving the chapter on “Heinrich Schenker” the final word in the section on “Tonality,” where it rounds out the entire enterprise of Part II of the book, “Regulative Traditions.” The author of the chapter, William Drabkin, attests to Schenker’s culminating image when he writes that “[Schenker’s theory] is at once a sophisticated explanation of tonality, but also an analytical system of immense empirical power. -

Schenker's Theory of Music As Ethics

Schenker's Theory of Music as Ethics NICHOLAS COOK Downloaded from http://online.ucpress.edu/jm/article-pdf/7/4/415/193927/763775.pdf by guest on 23 August 2020 hen we read Schenker's writings today, we tend to pick out the plums and ignore the rest. We appropriate his analytical techniques and accept his insights into musical structure, performance and editorial practice, while ignoring the broader con- text of his philosophical and political views, or at best relegating them to the occasional footnote. Until recently, published editions of Schenker's writings embod- 415 ied this selective, or even censorious, approach to the extent of actu- ally deleting passages of the original that were considered unneces- sary or undesirable. Some of these deletions were concerned with purely technical issues; in his 1954 edition of Harmony (the first vol- ume of Schenker's "New Musical Theories and Fantasies"), Oswald Jonas omitted a few sections that were inconsistent with the later development of Schenker's theories, including, for instance, a discus- sion of the seventh-chord. Jonas presumably did this in order to trans- form "New Musical Theories and Fantasies" as a whole into the state- ment of a fully consistent dogma; this also explains his fierce defense of canonical Schenkerian theory against the extensions and adapta- tions of Schenker's ideas proposed by Felix Salzer and, later, Roy Travis.1 But when, in the following year, he edited Free Composition (the final volume of "New Musical Theories and Fantasies"), Jonas extended his policy of deletion to Schenker's frequent excursions into metaphysics, religion and politics. -

Enharmonic Paradoxes in Classical, Neoclassical, and Popular Music By

Enharmonic Paradoxes in Classical, Neoclassical, and Popular Music by Haley Britt Beverburg Reale A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Music: Theory) in The University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Ramon Satyendra, Chair Professor Walter T. Everett Professor Kevin E. Korsyn Professor Herbert Graves Winful Associate Professor Wayne C. Petty © Haley Britt Beverburg Reale 2011 Dedication36B To my husband ii Acknowledgements37B I could not have completed this dissertation without the support of numerous people. I would especially like to thank my adviser, Ramon Satyendra, for his encouragement and boundless optimism through the whole process. He never failed to receive my ideas with enthusiasm and give me the confidence to pursue them, and his wide-ranging knowledge and helpful suggestions sparked many bursts of creativity over the past several years. I would also like to thank the other members of my dissertation committee— Kevin Korsyn, Wayne Petty, Walter Everett, and Herbert Winful—for their advice and support. Their expertise in diverse subjects was invaluable to me, and they were always willing and able to answer my many questions. I also had the privilege of working with and being inspired by many other faculty members at the University of Michigan. Special thanks to Karen Fournier for being a sounding board for many of my research ideas and for being a great listener. Additionally, I would like to acknowledge the Rackham School of Graduate Studies, especially Dean Steven M. Whiting, for financial support throughout my time at the University of Michigan. The teaching assistantships, fellowships, and travel grants for presenting at conferences gave me the means to pursue my research. -

Rock Harmony Reconsidered: Tonal, Modal and Contrapuntal Voice&

DOI: 10.1111/musa.12085 BRAD OSBORN ROCK HARMONY RECONSIDERED:TONAL,MODAL AND CONTRAPUNTAL VOICE-LEADING SYSTEMS IN RADIOHEAD A great deal of the harmony and voice leading in the British rock group Radiohead’s recorded output between 1997 and 2011 can be heard as elaborating either traditional tonal structures or establishing pitch centricity through purely contrapuntal means.1 A theory that highlights these tonal and contrapuntal elements departs from a number of developed approaches in rock scholarship: first, theories that focus on fretboard-ergonomic melodic gestures such as axe- fall and box patterns;2 second, a proclivity towards analysing chord roots rather than melody and voice leading;3 and third, a methodology that at least tacitly conflates the ideas of hypermetric emphasis and pitch centre. Despite being initially yoked to the musical conventions of punk and grunge (and their attendant guitar-centric compositional practice), Radiohead’s 1997– 2011 corpus features few of the characteristic fretboard gestures associated with rock harmony (partly because so much of this music is composed at the keyboard) and thus demands reconsideration on its own terms. This mature period represents the fullest expression of Radiohead’s unique harmonic, formal, timbral and rhythmic idiolect,4 as well as its evolved instrumentation, centring on keyboard and electronics. The point here is not to isolate Radiohead’s harmonic practice as something fundamentally different from all rock which came before it. Rather, by depending less on rock-paradigmatic gestures such as pentatonic box patterns on the fretboard, their music invites us to consider how such practices align with existing theories of rock harmony while diverging from others.