Composition, Perception, and Schenkerian Theory David Temperley

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Advanced Schenkerian Analysis: Perspectives on Phrase Rhythm, Motive, and Form by David Beach

Advanced Schenkerian Analysis: Perspectives on Phrase Rhythm, Motive, and Form by David Beach. New York and London: Routledge, 2012.1 Review by David Carson Berry After Allen Forte’s and Steven Gilbert’s Introduction to Schenkerian Analysis was published in 1982, it effectively had the textbook market to itself for a decade (a much older book by Felix Salzer and a new translation of one by Oswald Jonas not withstanding).2 A relatively compact Guide to Schenkerian Analysis, by David Neumeyer and Susan Tepping, was issued in 1992;3 and in 1998 came Allen Cadwallader and David Gagné’s Analysis of Tonal Music: A Schenkerian Approach, which is today (in its third edition) the dominant text.4 Despite its ascendance, and the firm legacy of the Forte/Gilbert book, authors continue to crowd what is a comparatively small market within music studies. Steven Porter offered the interesting but dubiously named Schenker Made Simple in 1 Advanced Schenkerian Analysis: Perspectives on Phrase Rhythm, Motive, and Form, by David Beach. New York and London: Routledge, 2012; hardback, $150 (978-0- 415-89214-8), paperback, $68.95 (978-0-415-89215-5); xx, 310 pp. 2 Allen Forte and Steven E. Gilbert, Introduction to Schenkerian Analysis (New York: Norton, 1982). Felix Salzer’s book (Structural Hearing: Tonal Coherence in Music [New York: Charles Boni, 1952]), though popular in its time, was viewed askance by orthodox Schenkerians due to its alterations of core tenets, and it was growing increasingly out of favor with mainstream theorists by the 1980s (as evidenced by the well-known rebuttal of its techniques in Joseph N. -

Science Fiction in Argentina: Technologies of the Text in A

Revised Pages Science Fiction in Argentina Revised Pages DIGITALCULTUREBOOKS, an imprint of the University of Michigan Press, is dedicated to publishing work in new media studies and the emerging field of digital humanities. Revised Pages Science Fiction in Argentina Technologies of the Text in a Material Multiverse Joanna Page University of Michigan Press Ann Arbor Revised Pages Copyright © 2016 by Joanna Page Some rights reserved This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- Noncommercial- No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA. Published in the United States of America by the University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid- free paper 2019 2018 2017 2016 4 3 2 1 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Page, Joanna, 1974– author. Title: Science fiction in Argentina : technologies of the text in a material multiverse / Joanna Page. Description: Ann Arbor : University of Michigan Press, [2016] | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2015044531| ISBN 9780472073108 (hardback : acid- free paper) | ISBN 9780472053100 (paperback : acid- free paper) | ISBN 9780472121878 (e- book) Subjects: LCSH: Science fiction, Argentine— History and criticism. | Literature and technology— Argentina. | Fantasy fiction, Argentine— History and criticism. | BISAC: LITERARY CRITICISM / Science Fiction & Fantasy. | LITERARY CRITICISM / Caribbean & Latin American. Classification: LCC PQ7707.S34 P34 2016 | DDC 860.9/35882— dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015044531 http://dx.doi.org/10.3998/dcbooks.13607062.0001.001 Revised Pages To my brother, who came into this world to disrupt my neat ordering of it, a talent I now admire. -

Computational Methods for Tonality-Based Style Analysis of Classical Music Audio Recordings

Fakult¨at fur¨ Elektrotechnik und Informationstechnik Computational Methods for Tonality-Based Style Analysis of Classical Music Audio Recordings Christof Weiß geboren am 16.07.1986 in Regensburg Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doktoringenieur (Dr.-Ing.) Angefertigt im: Fachgebiet Elektronische Medientechnik Institut fur¨ Medientechnik Fakult¨at fur¨ Elektrotechnik und Informationstechnik Gutachter: Prof. Dr.-Ing. Dr. rer. nat. h. c. mult. Karlheinz Brandenburg Prof. Dr. rer. nat. Meinard Muller¨ Prof. Dr. phil. Wolfgang Auhagen Tag der Einreichung: 25.11.2016 Tag der wissenschaftlichen Aussprache: 03.04.2017 urn:nbn:de:gbv:ilm1-2017000293 iii Acknowledgements This thesis could not exist without the help of many people. I am very grateful to everybody who supported me during the work on my PhD. First of all, I want to thank Prof. Karlheinz Brandenburg for supervising my thesis but also, for the opportunity to work within a great team and a nice working enviroment at Fraunhofer IDMT in Ilmenau. I also want to mention my colleagues of the Metadata department for having such a friendly atmosphere including motivating scientific discussions, musical activity, and more. In particular, I want to thank all members of the Semantic Music Technologies group for the nice group climate and for helping with many things in research and beyond. Especially|thank you Alex, Ronny, Christian, Uwe, Estefan´ıa, Patrick, Daniel, Ania, Christian, Anna, Sascha, and Jakob for not only having a prolific working time in Ilmenau but also making friends there. Furthermore, I want to thank several students at TU Ilmenau who worked with me on my topic. Special thanks go to Prof. -

Counterpoint MUS – Spring 2019

Counterpoint MUS – Spring 2019 Dr. Julia Bozone Monday and Wednesday at 11:00 - 11:50 in Rm. 214 Email: [email protected] Office Hours MWF 8:00-9:00, and By Appointment during 11-3 MWF Concurrent Enrollment: Required Materials: Counterpoint, Kent Kennan, 1999. A Practical Approach to 16th Century Counterpoint, Robert Gauldin A Practical Approach to 18th Century Counterpoint, Robert Gauldin Course Description: Theory II is the second in a four-semester sequence which examines the notational, harmonic, and compositional practices of the Western art- music tradition. This course emphasizes the development of analytical and compositional skills, with particular focus on the music of the Common Practice Era (CPE). Student Learning Outcomes: Upon successful completion of this course, students will be able to accomplish the following in each category: Melody Identify proper use of melodic contrapuntal lines Identify melodic properties: apex, sequences often found in melodic lines Harmony Construct and identify properly resolved interval relationships between voices Construct and identify chord progression for contrapuntal voicing. Demonstrate, through composition and analysis, an understanding of diatonic sequences Demonstrate, through composition and analysis, an understanding of common- practice functional harmony Rhythm Demonstrate, through composition and analysis, an understanding of rhythmic notation and of all common meters Composition Compose original works utilizing two and three voice counterpoint Course Requirements: There will be frequent homework assignments utilizing both analytical and compositional skills. All work should be done with either pencil or computer notation software. Homework is to be turned in during class on the day on which it is due. Late assignments will not be accepted for credit unless by previous arrangement with the instructor. -

Schenkerian Analysis in the Modern Context of the Musical Analysis

Mathematics and Computers in Biology, Business and Acoustics THE SCHENKERIAN ANALYSIS IN THE MODERN CONTEXT OF THE MUSICAL ANALYSIS ANCA PREDA, PETRUTA-MARIA COROIU Faculty of Music Transilvania University of Brasov 9 Eroilor Blvd ROMANIA [email protected], [email protected] Abstract: - Music analysis represents the most useful way of exploration and innovation of musical interpretations. Performers who use music analysis efficiently will find it a valuable method for finding the kind of musical richness they desire in their interpretations. The use of Schenkerian analysis in performance offers a rational basis and an unique way of interpreting music in performance. Key-Words: - Schenkerian analysis, structural hearing, prolongation, progression,modernity. 1 Introduction Even in a simple piece of piano music, the ear Musical analysis is a musicological approach in hears a vast number of notes, many of them played order to determine the structural components of a simultaneously. The situation is similar to that found musical text, the technical development of the in language. Although music is quite different to discourse, the morphological descriptions and the spoken language, most listeners will still group the understanding of the meaning of the work. Analysis different sounds they hear into motifs, phrases and has complete autonomy in the context of the even longer sections. musicological disciplines as the music philosophy, Schenker was not afraid to criticize what he saw the musical aesthetics, the compositional technique, as a general lack of theoretical and practical the music history and the musical criticism. understanding amongst musicians. As a dedicated performer, composer, teacher and editor of music himself, he believed that the professional practice of 2 Problem Formulation all these activities suffered from serious misunderstandings of how tonal music works. -

Further Considerations of the Continuous ^5 with an Introduction and Explanation of Schenker's Five Interruption Models

Further Considerations of the Continuous ^5 with an Introduction and Explanation of Schenker's Five Interruption Models By: Irna Priore ―Further Considerations about the Continuous ^5 with an Introduction and Explanation of Schenker’s Five Interruption Models.‖ Indiana Theory Review, Volume 25, Spring-Fall 2004 (spring 2007). Made available courtesy of Indiana University School of Music: http://www.music.indiana.edu/ *** Note: Figures may be missing from this format of the document Article: Schenker’s works span about thirty years, from his early performance editions in the first decade of the twentieth century to Free Composition in 1935.1 Nevertheless, the focus of modern scholarship has most often been on the ideas contained in this last work. Although Free Composition is indeed a monumental accomplishment, Schenker's early ideas are insightful and merit further study. Not everything in these early essays was incorporated into Free Composition and some ideas that appear in their final form in Free Composition can be traced back to his previous writings. This is the case with the discussion of interruption, a term coined only in Free Composition. After the idea of the chord of nature and its unfolding, interruption is probably the most important concept in Free Composition. In this work Schenker studied the implications of melodic descent, referring to the momentary pause of this descent prior to the achievement of tonal closure as interruption. In his earlier works he focused more on the continuity of the line itself rather than its tonal closure, and used the notion of melodic line or melodic continuity to address long-range connections. -

Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600

Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 By Leon Chisholm A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Kate van Orden, Co-Chair Professor James Q. Davies, Co-Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Massimo Mazzotti Summer 2015 Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 Copyright 2015 by Leon Chisholm Abstract Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 by Leon Chisholm Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Kate van Orden, Co-Chair Professor James Q. Davies, Co-Chair Keyboard instruments are ubiquitous in the history of European music. Despite the centrality of keyboards to everyday music making, their influence over the ways in which musicians have conceptualized music and, consequently, the music that they have created has received little attention. This dissertation explores how keyboard playing fits into revolutionary developments in music around 1600 – a period which roughly coincided with the emergence of the keyboard as the multipurpose instrument that has served musicians ever since. During the sixteenth century, keyboard playing became an increasingly common mode of experiencing polyphonic music, challenging the longstanding status of ensemble singing as the paradigmatic vehicle for the art of counterpoint – and ultimately replacing it in the eighteenth century. The competing paradigms differed radically: whereas ensemble singing comprised a group of musicians using their bodies as instruments, keyboard playing involved a lone musician operating a machine with her hands. -

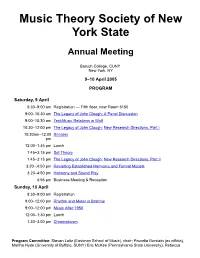

Program and Abstracts for 2005 Meeting

Music Theory Society of New York State Annual Meeting Baruch College, CUNY New York, NY 9–10 April 2005 PROGRAM Saturday, 9 April 8:30–9:00 am Registration — Fifth floor, near Room 5150 9:00–10:30 am The Legacy of John Clough: A Panel Discussion 9:00–10:30 am TextMusic Relations in Wolf 10:30–12:00 pm The Legacy of John Clough: New Research Directions, Part I 10:30am–12:00 Scriabin pm 12:00–1:45 pm Lunch 1:45–3:15 pm Set Theory 1:45–3:15 pm The Legacy of John Clough: New Research Directions, Part II 3:20–;4:50 pm Revisiting Established Harmonic and Formal Models 3:20–4:50 pm Harmony and Sound Play 4:55 pm Business Meeting & Reception Sunday, 10 April 8:30–9:00 am Registration 9:00–12:00 pm Rhythm and Meter in Brahms 9:00–12:00 pm Music After 1950 12:00–1:30 pm Lunch 1:30–3:00 pm Chromaticism Program Committee: Steven Laitz (Eastman School of Music), chair; Poundie Burstein (ex officio), Martha Hyde (University of Buffalo, SUNY) Eric McKee (Pennsylvania State University); Rebecca Jemian (Ithaca College), and Alexandra Vojcic (Juilliard). MTSNYS Home Page | Conference Information Saturday, 9:00–10:30 am The Legacy of John Clough: A Panel Discussion Chair: Norman Carey (Eastman School of Music) Jack Douthett (University at Buffalo, SUNY) Nora Engebretsen (Bowling Green State University) Jonathan Kochavi (Swarthmore, PA) Norman Carey (Eastman School of Music) John Clough was a pioneer in the field of scale theory. -

A Framework for Automated Schenkerian Analysis

ISMIR 2008 – Session 3b – Computational Musicology A FRAMEWORK FOR AUTOMATED SCHENKERIAN ANALYSIS Phillip B. Kirlin and Paul E. Utgoff Department of Computer Science University of Massachusetts Amherst Amherst, MA 01003 {pkirlin,utgoff}@cs.umass.edu ABSTRACT [1] in a hierarchical manner. Schenker’s theory of music al- lows one to determine which notes in a passage of music In Schenkerian analysis, one seeks to find structural de- are more structurally significant than others. It is important pendences among the notes of a composition and organize not to confuse “structural significance” with “musical im- these dependences into a coherent hierarchy that illustrates portance;” a musically important note (e.g., crucial for artic- the function of every note. This type of analysis reveals ulating correctly in a performance) can be a very insignifi- multiple levels of structure in a composition by construct- cant tone from a structural standpoint. Judgments regarding ing a series of simplifications of a piece showing various structural importance result from finding dependences be- elaborations and prolongations. We present a framework tween notes or sets of notes: if a note X derives its musical for solving this problem, called IVI, that uses a state-space function or meaning from the presence of another note Y , search formalism. IVI includes multiple interacting compo- then X is dependent on Y and Y is deemed more structural nents, including modules for various preliminary analyses than X. (harmonic, melodic, rhythmic, and cadential), identifying The process of completing a Schenkerian analysis pro- and performing reductions, and locating pieces of the Ur- ceeds in a recursive manner. -

MTO 15.2: Samarotto, Plays of Opposing Motion

Volume 15, Number 2, June 2009 Copyright © 2009 Society for Music Theory Frank Samarotto KEYWORDS: Schenker, Kurth, energetics, melodic analysis ABSTRACT: Rameau’s privileging of harmony over melody may be set against the pendulum swing of Kurth’s pure melodic energy. Although Schenker’s theory clearly identifies linear motion as governed by harmony, Schenker could still place great importance on melodic directionality and impulse as independent elements, even when they run counter to the harmonic setting or to the descending trajectory of the Urlinie. Extrapolating from Schenker’s work, this paper will examine what I call contra-structural melodic impulses, characterized by two aspects: directionality and ambitus, and acting as a compositionally significant counter pull to the tonal structure. Received October 2008 [1] Rameau’s seminal treatise of 1722 opens with a powerful declaration: the science of music is divided into melody and harmony, but, he says, . a knowledge of harmony is sufficient for a complete understanding of music (Rameau 1971, 3, editorial fn. 1). Indeed, an annotation in a contemporary copy adds that this makes a “remarkable statement: harmony and melody are inseparable” (Rameau 1971). It is a remarkable statement, especially when understood in light of Rameau’s progression of the fundamental bass, the progenitor of all later theories of harmony. Rameau’s cadence parfaite gathered together the contrapuntal threads of individual melodic lines and made them subordinates of, or at least co-conspirators with the root progression, which is a much more ideal concept.(1) Almost two centuries later, Ernst Kurth tried to detach melody entirely from harmony, hearing in Bach’s melodic lines an unbridled energy, careening about unrestrained by the bounds of harmony (Kurth 1917). -

Yale University Department of Music

Yale University Department of Music Review: A Commentary on Schenker's Free Composition Author(s): Carl E. Schachter Reviewed work(s): Free Composition (Der freie Satz) by Heinrich Schenker ; Ernst Oster Source: Journal of Music Theory, Vol. 25, No. 1, 25th Anniversary Issue (Spring, 1981), pp. 115-142 Published by: Duke University Press on behalf of the Yale University Department of Music Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/843469 Accessed: 14/01/2010 20:01 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=duke. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Duke University Press and Yale University Department of Music are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of Music Theory. -

A Schenkerian Analysis of Ravel's Introduction And

Schenkerian Analysis of Ravel A SCHENKERIAN ANALYSIS OF RAVEL’S INTRODUCTION AND ALLEGRO FROM THE BONNY METHOD OF GUIDED IMAGERY AND MUSIC Robert Gross, MM, MA, DMA ABSTRACT This study gathers image and emotional responses reported by Bruscia et al. (2005) to Ravel’s Introduction and Allegro, which is a work included for use in the Bonny Method of Guided Imagery and Music (BMGIM). A Schenkerian background of the Ravel is created using the emotional and image responses reported by Bruscia’s team. This background is then developed further into a full middleground Schenkerian analysis of the Ravel, which is then annotated. Each annotation observes some mechanical phenomenon which is then correlated to one or more of the responses given by Bruscia’s team. The argument is made that Schenkerian analysis can inform clinicians about the potency of the pieces they use in BMGIM, and can explain seemingly contradictory or incongruous responses given by clients who experience BMGIM. The study includes a primer on the basics of Schenkerian analysis and a discussion of implications for clinical practice. INTRODUCTION For years I had been fascinated by musical analysis. My interest began in a graduate-level class at Rice University in 1998 taught by Dr. Richard Lavenda, who, regarding our final project, had the imagination to say that we could use an analytical method of our devising. I invented a very naïve method of performing Schenkerian analysis on post-tonal music; the concept of post-tonal prolongation and the application of Schenkerian principles to post-tonal music became a preoccupation that has persisted for me to this day.