The Unbearable Heaviness of Jewish Self-Hatred

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

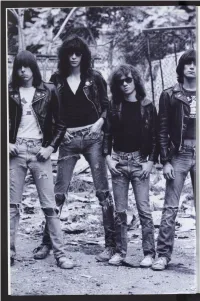

Ho! Let's Go: Ramones and the Birth of Punk Opening Friday, Sept

® The GRAMMY Museum and Delta Air Lines Present Hey! Ho! Let's Go: Ramones and the Birth of Punk Opening Friday, Sept. 16 Linda Ramone, Billy Idol, Seymour Stein, Shepard Fairey, And Monte A. Melnick To Appear At The Museum Opening Night For Special Evening Program LOS ANGELES (Aug. 24, 2016) — Following its debut at the Queens Museum in New York, on Sept. 16, 2016, the GRAMMY Museum® at L.A. LIVE and Delta Air Lines will present the second of the two-part traveling exhibit, Hey! Ho! Let's Go: Ramones and the Birth of Punk. On the evening of the launch, Linda Ramone; British pop/punk icon Billy Idol; Seymour Stein, Vice President of Warner Bros. Records and a co-founder of Sire Records, the label that signed the Ramones to their first record deal; artist Shepard Fairey; and Monte A. Melnick, longtime tour manager for the Ramones, will participate in an intimate program in the Clive Davis Theater at 7:30 p.m. titled "Hey! Ho! Let’s Go: Celebrating 40 Years Of The Ramones." Tickets can be purchased at AXS.com beginning Thursday, Aug. 25 at 10:30 a.m. Co-curated by the GRAMMY Museum and the Queens Museum, in collaboration with Ramones Productions Inc., the exhibit commemorates the 40th anniversary of the release of the Ramones' 1976 self-titled debut album and contextualizes the band in the larger pantheon of music history and pop culture. On display through February 2017, the exhibit is organized under a sequence of themes — places, events, songs, and artists —and includes items by figures such as: Arturo Vega (who, along with the Ramones, -

Ramones 2002.Pdf

PERFORMERS THE RAMONES B y DR. DONNA GAINES IN THE DARK AGES THAT PRECEDED THE RAMONES, black leather motorcycle jackets and Keds (Ameri fans were shut out, reduced to the role of passive can-made sneakers only), the Ramones incited a spectator. In the early 1970s, boredom inherited the sneering cultural insurrection. In 1976 they re earth: The airwaves were ruled by crotchety old di corded their eponymous first album in seventeen nosaurs; rock & roll had become an alienated labor - days for 16,400. At a time when superstars were rock, detached from its roots. Gone were the sounds demanding upwards of half a million, the Ramones of youthful angst, exuberance, sexuality and misrule. democratized rock & ro|ft|you didn’t need a fat con The spirit of rock & roll was beaten back, the glorious tract, great looks, expensive clothes or the skills of legacy handed down to us in doo-wop, Chuck Berry, Clapton. You just had to follow Joey’s credo: “Do it the British Invasion and surf music lost. If you were from the heart and follow your instincts.” More than an average American kid hanging out in your room twenty-five years later - after the band officially playing guitar, hoping to start a band, how could you broke up - from Old Hanoi to East Berlin, kids in full possibly compete with elaborate guitar solos, expen Ramones regalia incorporate the commando spirit sive equipment and million-dollar stage shows? It all of DIY, do it yourself. seemed out of reach. And then, in 1974, a uniformed According to Joey, the chorus in “Blitzkrieg Bop” - militia burst forth from Forest Hills, Queens, firing a “Hey ho, let’s go” - was “the battle cry that sounded shot heard round the world. -

Rhino Reissues the Ramones' First Four Albums

2011-07-11 09:13 CEST Rhino Reissues The Ramones’ First Four Albums NOW I WANNA SNIFF SOME WAX Rhino Reissues The Ramones’ First Four Albums Both Versions Available July 19 Hey, ho, let’s go. Rhino celebrates the Ramones’ indelible musical legacy with reissues of the pioneering group’s first four albums on 180-gram vinyl. Ramones, Leave Home, Rocket To Russia and Road To Ruin look amazing and come in accurate reproductions of the original packaging. More importantly, the records sound magnificent and were made using lacquers cut from the original analog masters by Chris Bellman at Bernie Grundman Mastering. For these releases, Rhino will – for the first time ever on vinyl – reissue the first pressing of Leave Home, which includes “Carbona Not Glue,” a track that was replaced with “Sheena Is A Punk Rocker” on all subsequent pressings. Joey, Johnny, Dee Dee and Tommy Ramone. The original line-up – along with Marky Ramone who joined in 1978 – helped blaze a trail more than 30 years ago with this classic four-album run. It’s hard to overstate how influential the group’s signature sound – minimalist rock played at maximum volume – was at the time, and still is today. These four landmark albums – Ramones (1976), Leave Home (1977), Rocket To Russia (1977) and Road to Ruin (1978) – contain such unforgettable songs as: “Blitzkrieg Bop,” “Sheena Is Punk Rocker,” “Beat On The Brat,” “Now I Wanna Sniff Some Glue,” “Pinhead,” “Rockaway Beach” and “I Wanna Be Sedated.” RAMONES Side One Side Two 1. “Blitzkrieg Bop” 1. “Loudmouth” 2. “Beat On The Brat” 2. -

Dee Dee Ramone Sees No Need to Change Course by KARLA TIPTON an Interview with the Valley Acterized Many Punk Bands

Friday, July 1,1988. Antdope Valley Press Dee Dee Ramone sees no need to change course BY KARLA TIPTON an interview with the Valley acterized many punk bands. ~ssisfantShowcase Editor Press. "Our goal isn't really to "Our songs aren't political and he Ramones haven't get that slick, commercial sound. more fun," said Dee Dee.. gmwn up at all. What's What it is is to preserve the 'They're mare animated-type more, they don't show Ramones sound." songs We've staved away frum any signs of it - even Now in the midst of a nation- the heavy message or shack for afterT 15 years. wrde tour, thas raucous punk.roh the sake bf v~olei&. On their latest Sire LP power pop band will be bnngmg "Oui influences are more like Ramonesmania. a cornoilation of that sound to the L,s Anrelts the Beatles and the Beach Bovs the band's most rhemorable area when they perform a< the along with all the glitter pub songs, the Ramones' steadfast- Holly~+oodPalladium (July a), &om the early '70s. So we have a ness to their musical vision of the Celebrity Theater in Ana- little bit of pop in us." wngue.~n.eheek deadpan lyrrcs heim (July 15) and the John An- That pop influence even turns and raptd-fire thnr chord aongs son Ford Theatre in Hollywood up in the band's monikei Com- hecomeb lmmedlstelv aooarenr (July 16). Dosed of Johnnv. Markv. Joev TG~"band's Defined, the Ramones' sound and Dee Dee aho one, the mem. -

I Hope You're Available to Swing by the Newseum This Evening As the National Park Trust Honors Senator Martin Heinrich (June 13Th at 6:30 PM)

Message From: Knauss, Chuck [[email protected]] Sent: 6/13/2018 4:40:24 PM To: Wehrum, Bill [/o=Exchangelabs/ou=Exchange Administrative Group (FYDI BO HF 23SPDL T)/cn=Recip ients/en =33d96a e800cf43a391 ld94a 7130b6c41-Weh rum, Wil] Subject: Invitation for tonight -- yes I know it's late ... Attachments: 2018 Bruce F Vento Public Service Award lnvitation.s-c-c-c-c.pdf Bill: Please come tonight and share with others that might be interested. ! I hope you're available to swing by the Newseum this evening as the National Park Trust honors Senator Martin Heinrich (June 13th at 6:30 PM). As you know, I'm on the NPT board and our mission is very important to me - protecting high priority lands for the National Park Service and creating future park stewards, with a special emphasis on children from under-served communities. Each year we host the Bruce F. Vento Public Service Award event to honor an outstanding elected official and conservationist and celebrate NPT's accomplishments. The invitation is below and attached. The short program will give you a chance to hear about the important and effective projects we have underway and the highlight of the evening is hearing directly from some over the under-served children in our programs. The event includes a reception with the 30-minute formal program starting at 7:00 PM. Best regards, Chuck Sierra Club v. EPA 18cv3472 NDCA Tier 1 ED_002061_00180418-00001 Sierra Club v. EPA 18cv3472 NDCA Tier 1 ED_002061_00180418-00002 Sierra Club v. EPA 18cv3472 NDCA Tier 1 ED_002061_00180418-00003 Bruce E Vento Public Service Award Recipients JOHL C'Jn<Jrntt'Nnm:m Sett; McCdkm, Minntrna 2th Ss>ndM fbb h)r!nvm. -

The Long History of Indigenous Rock, Metal, and Punk

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Not All Killed by John Wayne: The Long History of Indigenous Rock, Metal, and Punk 1940s to the Present A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in American Indian Studies by Kristen Le Amber Martinez 2019 © Copyright by Kristen Le Amber Martinez 2019 ABSTRACT OF THESIS Not All Killed by John Wayne: Indigenous Rock ‘n’ Roll, Metal, and Punk History 1940s to the Present by Kristen Le Amber Martinez Master of Arts in American Indian Studies University of California Los Angeles, 2019 Professor Maylei Blackwell, Chair In looking at the contribution of Indigenous punk and hard rock bands, there has been a long history of punk that started in Northern Arizona, as well as a current diverse scene in the Southwest ranging from punk, ska, metal, doom, sludge, blues, and black metal. Diné, Apache, Hopi, Pueblo, Gila, Yaqui, and O’odham bands are currently creating vast punk and metal music scenes. In this thesis, I argue that Native punk is not just a cultural movement, but a form of survivance. Bands utilize punk and their stories as a conduit to counteract issues of victimhood as well as challenge imposed mechanisms of settler colonialism, racism, misogyny, homophobia, notions of being fixed in the past, as well as bringing awareness to genocide and missing and murdered Indigenous women. Through D.I.Y. and space making, bands are writing music which ii resonates with them, and are utilizing their own venues, promotions, zines, unique fashion, and lyrics to tell their stories. -

Robfreeman Recordingramones

Rob Freeman (center) recording Ramones at Plaza Sound Studios 1976 THIRTY YEARS AGO Ramones collided with a piece of 2” magnetic tape like a downhill semi with no brakes slamming into a brick wall. While many memories of recording the Ramones’ first album remain vivid, others, undoubtedly, have dulled or even faded away. This might be due in part to the passing of years, but, moreover, I attribute it to the fact that the entire experience flew through my life at the breakneck speed of one of the band’s rapid-fire songs following a heady “One, two, three, four!” Most album recording projects of the day averaged four to six weeks to complete; Ramones, with its purported budget of only $6000, zoomed by in just over a week— start to finish, mixed and remixed. Much has been documented about the Ramones since their first album rocked the New York punk scene. A Google search of the Internet yields untold numbers of web pages filled with a myriad of Ramones facts and an equal number of fictions. (No, Ramones was not recorded on the Radio City Music Hall stage as is so widely reported…read on.) But my perspective on recording Ramones is unique, and I hope to provide some insight of a different nature. I paint my recollections in broad strokes with the following… It was snowy and cold as usual in early February 1976. The trek up to Plaza Sound Studios followed its usual path: an escape into the warm refuge of Radio City Music Hall through the stage door entrance, a slow creep up the private elevator to the sixth floor, a trudge up another flight -

Die Ramones Als Helden Der Pop-Kultur

Nutzungshinweis: Es ist erlaubt, dieses Dokument zu drucken und aus diesem Dokument zu zitieren. Wenn Sie aus diesem Dokument zitieren, machen Sie bitte vollständige Angaben zur Quelle (Name des Autors, Titel des Beitrags und Internet-Adresse). Jede weitere Verwendung dieses Dokuments bedarf der vorherigen schriftlichen Genehmigung des Autors. Quelle: http://www.mythos-magazin.de CHRISTIAN BÖHM Die Ramones als Helden der Pop-Kultur Inhalt 1. Einleitung 2. Punk und Pop 2.1 Punk und Punk Rock: Begriffsklärung und Geschichte 2.1.1 Musik und Themen 2.1.2 Kleidung 2.1.3 Selbstverständnis und Motivation 2.1.4 Regionale Besonderheiten 2.1.5 Punk heute 2.2 Exkurs: Pop-Musik und Pop-Kultur 2.3 Rekurs: Punk als Pop 3. Mythen, Helden und das Star-System 3.1 Der traditionelle Mythos- und Helden-Begriff 3.2 Der moderne Helden- bzw. Star-Begriff innerhalb des Star-Systems 4. Die Ramones 4.1 Einführung in das ‚ Wesen ’ Ramones 4.1.1 Kurze Biographie der Ramones 4.1.2 Musikalische Charakteristika 4.2 Analysen und Interpretationen 4.2.1 Analyse von Presseartikeln und Literatur 4.2.1.1 Zur Ästhetik der Ramones 4.2.1.1.1 Die Ramones als ‚ Familie ’ 4.2.1.1.2 Das Band-Logo 4.2.1.1.3 Minimalismus 4.2.1.2 Amerikanischer vs. britischer Punk: Vergleich von Ramones und Sex Pistols 4.2.1.3 Die Ramones als Helden 4.2.1.4 Eine typisch amerikanische Band? 4.2.2 Analyse von Ramones-Songtexten 4.2.2.1 Blitzkrieg Bop 4.2.2.2 Sheena Is A Punk Rocker 4.2.2.3 Häufig vorkommende Motive und Thematiken in Texten der Ramones 4.2.2.3.1 Individualismus 4.2.2.3.2 Motive aus dem Psychiatrie- Comic- und Horror-Kontext 4.2.2.3.3 Das Deutsche als Klischee 4.2.2.3.4 Spaß / Humor 4.3 Der Film Rock’n’Roll High School 4.3.1 Kurze Inhaltsangabe des Films 4.3.2 Analyse und Interpretation des Films 4.3.2.1 Die Protagonistin: Riff Randell [...] Is A Punk Rocker 4.3.2.2 Die Antagonistin: Ms. -

Sun.Aug.23.15 195 Songs, 12.3 Hours, 1.47 GB

Page 1 of 6 .Sun.Aug.23.15 195 songs, 12.3 hours, 1.47 GB Name Time Album Artist 1 Peaks Song 3:27 Silence Is A Weapon Blackfire 2 I Can't Give You Anything 2:01 Rocket To Russia The Ramones 3 The Cutter 3:50 U2 Jukebox Echo & The Bunnymen 4 Donations 3 w/id Julie 0:24 KSZN Broadcast Clips Julie 5 Glad To See You Go 2:12 U2 Jukebox The Ramones 6 Wake Up 5:31 U2 Jukebox The Arcade Fire 7 Grey Will Fade 4:45 U2 Jukebox Charlotte Hatherley 8 Obstacle 1 4:10 U2 Jukebox Interpol 9 Pagan Lovesong 3:27 U2 Jukebox Virgin Prunes 10 Volunteer 2 Julie 0:48 KSZN Broadcast Clips Julie 11 30 Seconds Over Tokyo 6:21 U2 Jukebox Pere Ubu 12 Hounds Of Love 3:02 U2 Jukebox The Futureheads 13 Cattle And Cane 4:14 U2 Jukebox The Go-Betweens 14 A Forest 5:54 U2 Jukebox The Cure 15 The Cutter 3:50 U2 Jukebox Echo & The Bunnymen 16 Christine 2:58 U2 Jukebox Siouxsie & The Banshees 17 Glad To See You Go 2:12 U2 Jukebox The Ramones 18 Tell Me You Love Me 2:33 Strictly Commercial Frank Zappa 19 Peaches En Regalia 3:37 Strictly Commercial Frank Zappa 20 Don't Eat The Yellow Snow (Singl… 3:35 Strictly Commercial Frank Zappa 21 My Guitar Wants To Kill Your Mama 3:32 Strictly Commercial Frank Zappa 22 COPE-Terry 0:33 23 The Way It Is 2:22 The Strokes 24 Delicious Demon 2:42 Life's Too Good Sugarcubes 25 Tumble In The Rough 3:19 Tiny Music.. -

Trajetórias De Vida Em Perspectiva Histórica: Joey Ramone E Marky Ramone Life Trajectories in Historical Perspective: Joey Ramone and Marky Ramone

http//dx.doi.org/10.15448/21778-3748.2019.1.32926 Trajetórias de vida em perspectiva histórica: Joey Ramone e Marky Ramone Life trajectories in historical perspective: Joey Ramone and Marky Ramone Fernando Mendes Coelho1 Resumo: este artigo tem como objetivo discutir alguns elementos que marcaram a geração de jovens norte-ame- ricanos dos anos 1960 e do início dos anos 1970, a qual, após o final da Segunda Guerra Mundial, experimentou um período de insatisfação política e social, que levou a inúmeras contestações frente aos comportamentos conservadores estabelecidos até então. Desta forma procuraremos, a partir da análise de alguns trechos de obras autobiográfica e biográfica dos músicos Marky Ramone e Joey Ramone, identificar como os jovens, an- tes de se tornarem astros do rock mundial, enfrentavam os dilemas políticos e culturais dos Estados Unidos, como a repulsa à Guerra do Vietnã, os atritos com a geração dos seus pais e a negação ao movimento hippie. Discutiremos que o surgimento da contracultura apresentou diversas vertentes e, que em contradição aos que apenas queriam paz e amor, havia nos subúrbios urbanos algo mais agressivo, que veio posteriormente a se estruturar como o movimento punk. Todos esses elementos perpassam as incertezas dos anos de juventude dos nossos personagens, que são o centro do objeto da pesquisa, e com a utilização de análises biográficas como fontes de pesquisa histórica, procuraremos explorar as possibilidades metodológicas deste campo teórico para consolidar a argumentação desta pesquisa. Palavras-chave: Contracultura. Punk rock. Juventude. Estados Unidos. Abstract: this article aims to discuss some elements that marked the generation of American youth of the 1960s and early 1970s, which, after the end of World War II, experienced a period of political and social discontent that led to numerous conservative behaviors established so far.