Arxiv:2006.03163V1 [Astro-Ph.GA] 4 Jun 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Parkes H I Survey of the Magellanic System

A&A 432, 45–67 (2005) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361:20040321 & c ESO 2005 Astrophysics The Parkes H I Survey of the Magellanic System C. Brüns1,J.Kerp1, L. Staveley-Smith2, U. Mebold1,M.E.Putman3,R.F.Haynes2, P. M. W. Kalberla1,E.Muller4, and M. D. Filipovic2,5 1 Radioastronomisches Institut, Universität Bonn, Auf dem Hügel 71, 53121 Bonn, Germany e-mail: [email protected] 2 Australia Telescope National Facility, CSIRO, PO Box 76, Epping NSW 1710, Australia 3 Department of Astronomy, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, USA 4 Arecibo Observatory, HC3 Box 53995, Arecibo, PR 00612, USA 5 University of Western Sydney, Locked Bag 1797, Penrith South, DC, NSW 1797, Australia Received 24 February 2004 / Accepted 27 October 2004 Abstract. We present the first fully and uniformly sampled, spatially complete H survey of the entire Magellanic System with high velocity resolution (∆v = 1.0kms−1), performed with the Parkes Telescope. Approximately 24 percent of the southern skywascoveredbythissurveyona≈5 grid with an angular resolution of HPBW = 14.1. A fully automated data-reduction scheme was developed for this survey to handle the large number of H spectra (1.5 × 106). The individual Hanning smoothed and polarization averaged spectra have an rms brightness temperature noise of σ = 0.12 K. The final data-cubes have an rms noise of σrms ≈ 0.05 K and an effective angular resolution of ≈16 . In this paper we describe the survey parameters, the data- reduction and the general distribution of the H gas. The Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC) and the Small Magellanic Cloud (SMC) are associated with huge gaseous features – the = Magellanic Bridge, the Interface Region, the Magellanic Stream, and the Leading Arm – with a total H mass of M(H ) 8 2 4.87 × 10 M d/55 kpc ,ifallH gas is at the same distance of 55 kpc. -

VMC – the VISTA Survey of the Magellanic System Metallicity Of

Dr Maria‐Rosa Cioni VMC – the VISTA survey of the Magellanic System (Gal-Exgal survey) Metallicity of stellar populaons Moon of stellar populaons ESO spectroscopic survey workshop ESO-Garching, Germany, 9-10 March 2009 The VISTA survey of the Magellanic System ESO Public Survey 2009-2014 The most sensive near‐IR survey across the LMC, SMC, The team Bridge and part of the Stream M. Cioni, K. Bekki, G. Clemenni, W. de Blok, J. Emerson, C. Evans, R. de Grijs, B. Gibson, L. Girardi, M. Groenewegen, 4m Telescope V. Ivanov, M. Marconi, C. Mastropietro, B. Moore, R. Napiwotzki, T. Naylor, J. Oliveira, V. Ripepi, J. van Loon, M. Wilkinson, P. Wood 1.5 deg2 FOV United Kingdom, Italy, Belgium, Chile, France, Switzerland, South Africa, Australia http://star.herts.ac.uk/~mcioni/vmc/ 0. Observe the Magellanic System 2 ≈180 deg 3 filters ‐ YJKs 15 epochs (12 in KS and 3 in YJ; once simultaneous colours) S/N=10 at: Y=21.9, J=21.4, Ks=20.3 (Ks≈19 single epoch) Seeing 0.8 arcsec – average Spaal resoluon 0.34 pix/arcsec (0.51 arcsec instrument PSF) Service mode observing 1840 hours / 240 nights http://star.herts.ac.uk/~mcioni/vmc/ I. Derive the spaally resolved SFH Synthec diagram of a typical LMC stellar field as expected from VMC data. This field covers 1 VISTA detector! Accuracy: metallicity S/N=10 0.1 dex and age 20% in 0.1 deg2 Kerber et al 2009 http://star.herts.ac.uk/~mcioni/vmc/ II. Trace the 3D structure as a funcon of me The LMC is a few kpc thick and the SMC up to 20 kpc RR Lyrae stars are excellent distance indicators in the near‐IR First applicaon to the LMC bar to derive the LMC distance (Szewczyk et al 2008) – 0.2 kpc accuracy The structure of the Magellanic System will be measured using Cepheid variables, the red clump luminosity, the p of the red giant brach, etc. -

The Magellanic System's Interactive Formations

Publ. Astron. Soc. Aust., 2000, 17, 1–5. The Magellanic System’s Interactive Formations M. E. Putman Research School of Astronomy & Astrophysics, Australian National University, Private Bag, Weston Creek PO, ACT 2611, Australia [email protected] Received 1999 November 17, accepted 2000 January 7 Abstract: The interaction between the Galaxy and the Magellanic Clouds has resulted in several high-velocity complexes which are connected to the Clouds. The complexes are known as the Magellanic Bridge, an HI connection between the Large and Small Magellanic Clouds, the Magellanic Stream, a 10 100 HI lament which trails the Clouds, and the Leading Arm, a diuse HI lament which leads the Clouds. The mechanism responsible for these features formation remains under some debate, with the lack of detailed HI observations being one of the limiting factors in resolving the issue. Here I present several large mosaics of HI Parkes All-Sky Survey (HIPASS) data which show the full extent of the three Magellanic complexes at almost twice the resolution of previous observations. These interactive features are connected, but unique in their spatial and velocity distribution. The dierences may shed light on their origin and present environment. Dense clumps of HI along the sightline to the Sculptor Group, which may or may not be associated with the Magellanic complexes, are also discussed. Keywords: intergalactic medium — Local Group — Magellanic Clouds — galaxies: HI 1 Introduction this by providing a marked improvement in spatial Almost every galaxy in the Universe is either resolution compared to previous HVC surveys (see currently, or was at some time, part of an interacting Putman & Gibson 1999), and revealing previously system. -

R. Wagner-Kaiser

R. Wagner-Kaiser Email: [email protected] • Phone: (269) 274-1318 LinkedIn: linkedin.com/in/rawagnerkaiser • GitHub: github.com/rwk506 Webpage: astro.ufl.edu/~rawagnerkaiser/Home.html Stellar Populations • Globular Clusters & Multiple Populations • Variable Stars My interests in astronomy are centered around utilizing the power of stellar populations to learn more about the characteristics of galaxies, from the Milky Way to the Local Group to even further away external galaxies. Through observations of star clusters, variable stars, and resolved galactic stellar populations, I hope to learn more about the formation and evolution of galaxies in our universe. Education University of Florida 2011 – Present M.S. Astronomy: 2013 Gainesville, FL PhD Astronomy: 2016; GPA: 4.0 Dissertation: Bayesian Analysis of Globular Clusters – using a sophisticated Bayesian statistical technique to compare multi- dimensional theoretical models to observed data to determine the most likely parameters that describe object of interest. Vassar College 2006 – 2010 B.A. Physics, B.A. Astronomy (2010) Poughkeepsie, NY Minor equivalent in Mathematics GPA: 3.62; Graduated with Honors First Author Papers • Submitted (10.6.16): Wagner-Kaiser, R. and Sarajedini, A., 2016, MNRAS, Ages in the Local Solar Neighborhood from the JK turndown. • Accepted (2.28.17): Wagner-Kaiser, R., Sarajedini, A., von Hippel, T., Anderson, J., et al., 2016, MNRAS, The ACS Survey of Galactic Globular Clusters XIV: Bayesian Analysis of “Single” Stellar Populations of 69 Globular Clusters. • Accepted (12.5.16): Wagner-Kaiser, R. and Sarajedini, A., 2016, MNRAS, The properties of the Magellanic Bridge Based on OGLE IV Photometry of RR Lyrae Stars. • Wagner-Kaiser, R., Stenning, D., Robinson, E., von Hippel, T., Sarajedini, A., van Dyk, D. -

Hydrogen Clouds in the Magellanic System

Hydrogen clouds in the Magellanic System Bi-Qing For ICRAR/UWA The Magellanic System (HI) Leading Arm(s) LMC SMC Magellanic Stream Magellanic Bridge Image credit: Nidever et al. (2010) 2 Leading Arm(s) & Magellanic Stream Studies For et al. (2013): GASS For et al. (2014): GASS+ATCA ● HVCs catalogs (morphology – head-tail etc) ● Investigating the the effects of interaction with the Galactic halo ● Formation mechanism and compare to simulations 33 Narrow line width HVCs • Narrow line width HVCs • Cold: how do cold clouds survive in the hot halo? For et al. (2013) 44 Two phase medium (stable) Cold cloud is surrounded by a warm envelope Follow up observation with ATCA: For et al (2016) 55 Probing Environmental Effect • Deriving the physical parameters and properties • Resolving multiphase structure 66 GASS 77 ATCA ● Red: 12% peak sensitivity ● P/k = nTk ● Tk: Linewidth ● n: assumed distance, measured angular diameter ● Phase diagram: P/k vs n 88 HVC phase diagram Filled: 25kpc Non-filled: 50 pc Wolfire et al. (1995) Stable two-phase medium: Pmin< P < Pmax 99 Halo Environment as a Function of Galactic Latitude • Assuming hydrostatic equilibrium: thermal P = external halo thermal P • Galactic latitude proxy of z • Clouds reside in a denser halo environment at higher Galactic latitude 1010 • • Decreasing z Evidence LA I (Venzmer et al. 2013) LAEvidence I(Venzmer HI clouds compact possibleof evidence First Denser In short distance gradientdistance in the LA using region 11 11 GASKAP: Milky Way disk + Magellanic System ● PIs: J. Dickey + N. McClure-Griffiths ● 21 cm line + three 18 cm lines of OH molecule ● HI absorption and emission ● Magellanic System: 13020 sq deg ● resolution (~30 arcsec), velocity line width (1 km/s) 12 GASKAP: Magellanic System Figure: The GASKAP MS survey area with axes labeled in MS coordinates and Hi column densities from the LAB survey in the background (Nidever et al. -

Properties of Stellar Generations in Globular Clusters and Relations With

Astronomy & Astrophysics manuscript no. carretta c ESO 2018 November 9, 2018 Properties of stellar generations in Globular Clusters and relations with global parameters ⋆ E. Carretta1, A. Bragaglia1, R.G. Gratton2, A. Recio-Blanco3, S. Lucatello2,4, V. D’Orazi2, and S. Cassisi5 1 INAF-Osservatorio Astronomico di Bologna, via Ranzani 1, I-40127 Bologna, Italy 2 INAF-Osservatorio Astronomico di Padova, vicolo dell’Osservatorio 5, I-35122 Padova, Italy 3 Laboratoire Cassiop´ee UMR 6202, Universit`ede Nice Sophia-Antipolis, CNRS, Observatoire de la Cote d’Azur, BP 4229, 06304 Nice Cedex 4, France 4 Excellence Cluster Universe, Technische Universit¨at M¨unchen, Boltzmannstr. 2, D-85748, Garching, Germany 5 INAF-Osservatorio Astronomico di Collurania, via M. Maggini, I-64100 Teramo, Italy Received .....; accepted ..... ABSTRACT We revise the scenario of the formation of Galactic globular clusters (GCs) by adding the observed detailed chemical composition of their different stellar generations to the set of their global parameters. We exploit the unprecedented set of homogeneous abundances of more than 1200 red giants in 19 clusters, as well as additional data from literature, to give a new definition of bona fide globular clusters, as the stellar aggregates showing the presence of the Na-O anticorrelation. We propose a classification of GCs according to their kinematics and location in the Galaxy in three populations: disk/bulge, inner halo, and outer halo. We find that the luminosity function of globular clusters is fairly independent of their population, suggesting that it is imprinted by the formation mechanism, and only marginally affected by the ensuing evolution. We show that a large fraction of the primordial population should have been lost by the proto-GCs. -

Interstellar Media in the Magellanic Clouds and Other Local Group Dwarf Galaxies

Interstellar Media in the Magellanic Clouds and other Local Group Dwarf Galaxies Eva K. Grebel1 1Max-Planck-Institut f¨ur Astronomie, K¨onigstuhl 17, D-69117 Heidelberg, Germany Abstract. I review the properties of the interstellar medium in the Magellanic Clouds and Local Group dwarf galaxies. The more massive, star-forming galaxies show a complex, multi-phase ISM full of shells and holes ranging from very cold phases (a few 10 K) to extremely hot gas (> 106 K). In environments with high UV radiation fields the formation of molecular gas is suppressed, while in dwarfs with low UV fields molecular gas can form at lower than typical Galactic column densities. There is evidence of ongoing interactions, gas accretion, and stripping of gas in the Local Group dwarfs. Some dwarf galaxies appear to be in various stages of transition from gas-rich to gas-poor systems. No ISM was found in the least massive dwarfs. 1 Introduction There are currently 36 known and probable galaxy members of the Local Group within a zero-velocity surface of 1.2 Mpc. Except for the three spiral galaxies M31, Milky Way, and M33, the irregular Large Magellanic Cloud, and the small elliptical galaxy M32 all other galaxies in the Local Group are dwarf galaxies with MV > −18 mag. In this review I will concentrate on the properties of the interstellar medium (ISM) of the Magellanic Clouds and the Local Group dwarf galaxies, moving from gas-rich to gas-poor objects. Recent results from telescopes, instruments, and surveys such as NANTEN, ATCA, HIPASS, JCMT, ISO, ROSAT, FUSE, ORFEUS, STIS, Keck, and the VLT are significantly advancing our knowledge of the ISM in nearby dwarfs and provide an unprecedented, multi-wavelength view of its different phases. -

E+FW Abstract Book

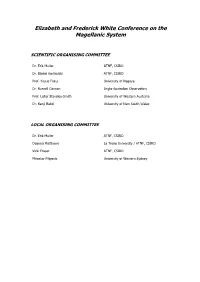

Elizabeth and Frederick White Conference on the Magellanic System SCIENTIFIC ORGANISING COMMITTEE Dr. Erik Muller ATNF, CSIRO Dr. Bärbel Koribalski ATNF, CSIRO Prof. Yasuo Fukui University of Nagoya Dr. Russell Cannon Anglo-Australian Observatory Prof. Lister Staveley-Smith Univeristy of Western Australia Dr. Kenji Bekki University of New South Wales LOCAL ORGANISING COMMITTEE Dr. Erik Muller ATNF, CSIRO Deanna Matthews La Trobe University / ATNF, CSIRO Vicki Fraser ATNF, CSIRO Miroslav Filipovic University of Western Sydney Elizabeth and Frederick White Conference on the Magellanic System PARTICIPANT LIST Bekki Kenji Univeristy of New South Wales Besla Gurtina Harvard-Smithsonian CfA Bland-Hawthorn Joss Anglo-Australian Observatory Bolatto Alberto UCB Bot Caroline California Institute of Technology Braun Robert Australia Telescope National Facility Brooks Kate Australia Telescope National Facility Cannon Russell Anglo-Australian Observatory Carlson Lynn Johns Hopkins University Cioni Maria-Rosa Institute for Astronomy, University of Edinburgh Da Costa Gary Research School of Astronomy & Astrophysics ANU Doi Yasuo University of Tokyo Ekers Ron Australia Telescope National Facility Filipovic Miroslav University of Western Sydney Fukui Yasuo Nagoya University Gaensler Bryan University of Sydney Harris Jason Steward Observatory Hitschfeld Marc University of Colgne Hughes Annie Centre for Astrophysics & Supercomputing, Swinburne University Hurley Jarrod Centre for Astrophysics & Supercomputing, Swinburne University Francisco Ibarra Javier -

![Arxiv:2007.00341V2 [Astro-Ph.GA] 7 Oct 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1243/arxiv-2007-00341v2-astro-ph-ga-7-oct-2020-1991243.webp)

Arxiv:2007.00341V2 [Astro-Ph.GA] 7 Oct 2020

MNRAS 000,1–23 () Preprint 8 October 2020 Compiled using MNRAS LATEX style file v3.0 A Search for star clusters in the outskirts of the Large Magellanic Cloud: indication of clusters in the age gap.¢ M. Gatto1,2,y V. Ripepi1, M. Bellazzini3, M. Cignoni4, M.-R. L. Cioni5, M. Dall’Ora1, G. Longo2, M. Marconi1, P. Schipani1, M. Tosi3 1 INAF-Osservatorio Astronomico di Capodimonte, Via Moiariello 16, 80131, Naples, Italy 2 Dept. of Physics, University of Naples Federico II, C.U. Monte Sant’Angelo, Via Cinthia, 80126, Naples, Italy 3 INAF-Osservatorio di Astrofisica e Scienza dello Spazio, Via Gobetti 93/3, I-40129 Bologna, Italy 4 Physics Departement, University of Pisa, Largo Bruno Pontecorvo, 3, I-56127 Pisa, Italy 5 Leibniz-Institut für Astrophysik Potsdam, An der Sternwarte 16, D-14482 Potsdam, Germany Accepted XXX. Received YYY; in original form ZZZ ABSTRACT The YMCA (Yes, Magellanic Clouds Again) and STEP (The SMC in Time: Evolution of a Prototype interacting late-type dwarf galaxy) projects are deep 6,8 photometric surveys carried out with the VLT Survey Telescope (VST) and devoted to study the outskirts of the Magellanic System. A main goal of YMCA and STEP is to identify candidate stellar clusters and complete their census out to the outermost regions of the Magellanic Clouds. We adopted a specific over-density search technique coupled with a visual inspection of the color magnitude diagrams (CMDs) to select the best candidates and estimate their ages. To date, we analysed a region of 23 sq. deg. in the outskirts of the Large Magellanic Cloud, detecting 85 candidate cluster candidates, 16 of which have estimated ages falling in the so called “age gap". -

Discovery of O Stars in the Tidal Magellanic Bridge: Stellar

Astronomy & Astrophysics manuscript no. main ©ESO 2020 November 17, 2020 Discovery of O stars in the tidal Magellanic Bridge Stellar parameters, abundances, and feedback of the nearest metal-poor massive stars and their implication for the Magellanic System ecology Varsha Ramachandran, L. M. Oskinova, and W.-R. Hamann Institut für Physik und Astronomie, Universität Potsdam, Karl-Liebknecht-Str. 24/25, D-14476 Potsdam, Germany e-mail: [email protected] Received <date> / Accepted <date> ABSTRACT The Magellanic Bridge stretching between the Small and the Large Magellanic Cloud (SMC and LMC), is the nearest tidally stripped intergalactic environment. The Bridge has a significantly low average metallicity of Z . 0:1Z . Here we report the first discovery of O-type stars in the Magellanic Bridge. Three massive O stars were identified thanks to the archival spectra obtained by the ESO’s Very Large Telescope FLAMES instrument. We analyze the spectra of each star using the advanced non-LTE stellar atmosphere model PoWR, which provides the physical parameters, ionizing photon fluxes, and surface abundances. The ages of the newly discovered O stars suggest that star formation in the Bridge is ongoing. Furthermore, the discovery of O stars in the Bridge implies that tidally stripped galactic tails containing low density but highly dynamical gas are capable of producing massive O stars. The multi-epoch spectra indicate that all three O stars are binaries. Despite their spatial proximity to each other, these O stars are chemically distinct. One of them is a fast-rotating giant with nearly LMC-like abundances. The other two are main-sequence stars that rotate extremely slowly and are strongly metal depleted. -

THE MAGELLANIC CLOUDS NEWSLETTER an Electronic Publication Dedicated to the Magellanic Clouds, and Astrophysical Phenomena Therein

THE MAGELLANIC CLOUDS NEWSLETTER An electronic publication dedicated to the Magellanic Clouds, and astrophysical phenomena therein No. 123 — 3 June 2013 http://www.astro.keele.ac.uk/MCnews Editor: Jacco van Loon Figure 1: Interstellar extinction map (left) and inferred molecular cloud map (right) around the Tarantula Nebula and Southern Molecular Ridge, based on VMC near-IR photometry of red clump stars – see Tatton et al. (2013) for more details. 1 Editorial Dear Colleagues, It is my pleasure to present you the 123rd issue of the Magellanic Clouds Newsletter. You have all been very busy. There are a lot of papers on pulsar(system)s, the Tarantula region, the Magellanic Stream and Bridge, and an exciting new proper motion study of the LMC. There is a fantastic opportunity to work with Sally Oey in Michigan – don’t miss it! The next issue is planned to be distributed on the 1st of August, 2013. Editorially Yours, Jacco van Loon 2 Refereed Journal Papers The VMC survey VII. Reddening map of the 30 Doradus field and the structure of the cold interstellar medium B.L. Tatton1, J.Th. van Loon1, M.-R. Cioni2,3, G. Clementini4, J.P. Emerson5, L. Girardi6, R. de Grijs7, M.A.T. Groenewegen8, M. Gullieuszik8, V.D. Ivanov9, M.I. Moretti4, V. Ripepi10 and S. Rubele6 1Astrophysics Group, Lennard-Jones Laboratories, Keele University, ST5 5BG, United Kingdom 2University of Hertfordshire, Physics Astronomy and Mathematics, Hatfield AL10 9AB, United Kingdom 3University Observatory Munich, Scheinerstraße 1, D-81679 M¨unchen, Germany 4INAF, Osservatorio Astronomico di Bologna, Via Ranzani 1, 40127 Bologna, Italy 5Astronomy Unit, School of Physics & Astronomy, Queen Mary University of London, Mile End Road, London E1 4NS, United Kingdom 6INAF, Osservatorio Astronomico di Padova, Vicolo dell’Osservatorio 5, 35122 Padova, Italy 7Kavli Institute for Astronomy and Astrophysics, Peking University, Yi He Yuan Lu 5, Hai Dian District, Beijing 100871, China 8Royal Observatory of Belgium, Ringlaan 3, 1180 Ukkel, Belgium 9European Southern Observatory, Santiago, Av. -

A Synoptic View of the Magellanic Clouds: VMC, Gaia, and Beyond Held at ESO Headquarters, Garching, Germany, 9–13 September 2019

Astronomical News DOI: 10.18727/0722-6691/5211 Report on the ESO Workshop A Synoptic View of the Magellanic Clouds: VMC, Gaia, and Beyond held at ESO Headquarters, Garching, Germany, 9–13 September 2019 Maria-Rosa L. Cioni 1 In this workshop, the most interesting of the system and use stellar population Martino Romaniello 2 discoveries emerging from the VMC and diagnostics across the Hertzsprung- Richard I. Anderson 2 other contemporary multi-wavelength Russell diagram with unprecedented pre- surveys were discussed. These results cision. Most of these developments will have cemented stellar populations as culminate in the early 2020s and discus- 1 Leibniz-Institut für Astrophysik Potsdam important diagnostics of galaxy proper- sions on how to formulate the most rele- (AIP), Germany ties. Cepheid stars have, for example, vant scientific questions are already 2 ESO revealed the three-dimensional structure advanced. of the system, giant stars have shown significantly extended populations, and The year 2019 marked the quincente- blue horizontal branch stars have indi- Summaries of talks and highlights from nary of the arrival in the southern hemi- cated protuberances and possible sessions sphere of Ferdinand Magellan, the streams in the outskirts of the galaxies. namesake of the Magellanic Clouds, The complementary view provided by The workshop revolved around eight our nearest example of dwarf galaxies RR Lyrae stars shows instead regular and scientific sessions at which a total of in the early stages of a minor merging ellipsoidal systems. The analysis of the 64 talks were presented and a summary event. These galaxies have been firmly star formation history suggests that the is given below.