Prairie Perspectives: Geographical Essays

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

May 1, 2016, Lazy Bones Travelogue, Virgin Islands And

May 1, 2016 Lazy Bones Update: British Virgin Islands (BVI’s), U.S. Virgin Islands, and Puerto Rico Our last update left off with us setting sail on March 14th from St Maarten, the most northerly of the Leeward Islands, to the British Virgin Islands (BVI’s). Our destination was the island of Virgin Gorda, 84 miles northwest. We left St. Maarten at 5:30 AM and experienced rain squalls most of the day, but we averaged over eight knots and even hit 10.2 knots! We arrived at Virgin Gorda North Sound at 3:30 PM and anchored off Prickly Pear Island. The next morning we took the dinghy across the sound to Gun Creek and cleared in with customs. We came back to Lazy Bones and motor-sailed over to the Bitter End Yacht Club (BEYC), anchored outside the mooring field, and went ashore for lunch. The BEYC is a unique nautical resort that caters to all yachtsmen. They have a small marina, several restaurants, friendly bars, a small grocery store, bungalows, Wi-Fi, a pool, and much more. It’s a great place to hang out, have some drinks, and enjoy a nice meal. At 4:30 we took the dinghy over to Saba Rock for happy hour. This tiny island was owned by Bert Kilbride, a big enthusiast for SCUBA diving, back in the fifties. In the sixties Bert opened the Pirates Pub, set up a few moorings, and Saba Rock became the local sailors’ hangout. In 1997, he sold out to a developer who built an amazing resort on this tiny piece of rock. -

A231 Virgin Islands St Thomas to Virgin Gorda

A231 Virgin Islands St Thomas to Virgin Gorda October 2019 Before using this chart visit Plans Charlotte Amalie (St Thomas), Cruz Bay (St John), www.imray.com Road Harbour, Sea Cow Bay & Nanny Cay Marina (Tortola), for the latest corrections Benner Bay (St Thomas), Great Camanoe to Scrub Island 1: 90 000 WGS 84 A A2 A1 L E A14 E W VIRGIN A11 A131 A231 A ISLANDS R D A3 PUERTO A141 A232 A24 Anguilla RICO A131 St Martin A12 A13 A234 A25 A23 St Croix A25 Barbuda A26 St Christopher A271 Nevis A27 Antigua A25 I S Montserrat L A N D A4 A28 S Guadeloupe A281 A281 Marie-Galante A29 Dominica Caribbean Sea B B5 Martinique A301 A30 St Lucia B1 B3 B30 MCA recognised MOBILE DOWNLOADS Imray-Iolaire Imray Navigator app CHARTS FOR THE EASTERN CARIBBEAN Digitally printed Donald M Street Jr on water resistant paper Ground swell A231 St Thomas to Virgin Gorda Ground swells are generated by storms in the North Atlantic and are completely The Virgin Islands are an archipelago archipelago lies along the length of so independent of the Caribbean weather of small islands divided into two main called ‘Hurricane Alley’ and is systems. From mid-October to April any groupings: The US Virgin Islands lie at vulnerable to the devastating effects anchorage open to the northwest is the western end of the group and are that these storms can bring (see vulnerable. If these swells take you by governed as an unincorporated Hurricanes). surprise and you are lying to a single anchor you may end up being driven ashore. -

A Cruising Guide to Puerto Rico

A Cruising Guide to Puerto Rico Ed. 1.0 by Frank Virgintino Flag of Puerto Rico Copyright © 2012 by Frank Virgintino. All rights reserved. www.freecruisingguides.com A Cruising Guide to Puerto Rico, Ed. 1.0 www.freecruisingguides.com 2 Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................. 10 1. PREFACE AND PORT REFERENCES ....................................... 12 SOUTH COAST ......................................................................... 13 EAST COAST ............................................................................ 14 Mainland ................................................................................ 14 Islands .................................................................................... 15 NORTH COAST ......................................................................... 15 WEST COAST ........................................................................... 16 2. INTRODUCING PUERTO RICO ................................................ 17 SAILING DIRECTIONS TO PUERTO RICO .............................. 17 From North: ............................................................................ 17 From South: ............................................................................ 21 From East: .............................................................................. 22 From West: ............................................................................. 22 PUERTO RICAN CULTURE ...................................................... 23 SERVICES -

Tourism Research in the British Virgin Islands

Prairie Perspectives 89 Chasing Twenty-first Century smokestacks: tourism research in the British Virgin Islands John Everitt, Department of Geography, Brandon University Abstract: “Chasing Smokestacks” has become well-known if not complimentary terminology to describe the actions of villages, towns, regions, and countries wanting instant economic development, often at almost any cost. In the past the smokestack referred to was a conventional industry – such as Maple Leaf Pork or J.R. Simplot (fertilizer production) in Brandon, or oil refineries and alumina smelters in St. Thomas (U.S. Virgin Islands). The contemporary smokestack for many places, such as the British Virgin Islands, is tourism — ironically stereotypified by the large smoke-stacked cruise ships of the Holland America Line or Cunard ships such as the Queen Mary 2. Although mass tourism cruise ships are only one part of the BVI tourist puzzle, they are seen to be important both financially and symbolically and are accepted at almost any cost. But tourism in the BVI is much more than what many feel are ‘down-market’ cruise ships and short-stay beach tourists. The BVI are also aiming for ‘up-market visitors’ such as those who own or rent yachts, dive and/or snorkel, as well as snowbirds who stay for greater lengths of time and expats who settle-in for several years and contribute significantly both to the economy and society of the Islands. Many of the former stay on their (or rented) yachts, buy from local businesses, and frequent locals restaurants and bars The snowbirds and expats typically live in large, expensive homes or villas that are keeping the construction industry at full stretch. -

January 2007

Diplomatic Security special agents arrive via ferry in the British Virgin Islands to con- duct a passport fraud investigation. San Juan Noche SMALL OFFICE PLAYS A BIG LAW ENFORCEMENT ROLE BY CHRISTOPHER TREMANN he smallest of the Greater officer in 1952 in a foiled attempt to assassi- weeks. Even as late as last December, anti- Antilles, Puerto Rico is an island nate President Truman. American graffiti could be seen scrawled on of contrasts and incredible In 1999, protests over the U.S. military highway ramps and the sides of buildings. beauty. It is a territory of the presence in Puerto Rico came to a head The only permanent Department of United States, so a tour there is when a civilian guard was killed on the State representation on the island is the San consideredT a domestic assignment. But with island of Vieques, to the east of Puerto Rico. Juan Resident Office, which reports to the its different language and culture, it can be Vieques, two-thirds of which was owned by Bureau of Diplomatic Security’s Miami an exciting, rewarding and culturally the U.S., was used by the Navy as a live- Field Office. It has both Foreign Service enriching experience. weapons testing ground. The protests and Civil Service positions: an FS resident While most Puerto Ricans are proud of received international attention, and in agent in charge, three FS special agents and their U.S. citizenship, a small but vocal 2003 the Navy left Puerto Rico and Vieques. a CS investigative assistant. The office is minority has advocated complete inde- In September 2005, agents from the expanding to include two Puerto Rico pendence. -

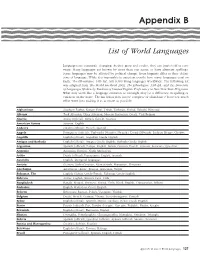

Bbbbbbbbbbbbbbb List of World Languages

Appendix B bbbbbbbbbbbbbbb List of World Languages Languages are constantly changing. As they grow and evolve, they can branch off or con- verge. Many languages are known by more than one name, or have alternate spellings. Some languages may be affected by political change. Even linguists differ in their defini- tions of language. While it is impossible to ascertain exactly how many languages exist on Earth, The Ethnologue, 14th Ed., lists 6,809 living languages worldwide. The following list was adapted from The World Factbook 2002, The Ethnologue, 14th Ed., and the Directory of Languages Spoken by Students of Limited English Proficiency in New York State Programs. What may seem like a language omission or oversight may be a difference in spelling or variation on the name. The list below may not be complete or all-inclusive; however, much effort went into making it as accurate as possible. Afghanistan Southern Pashto, Eastern Farsi, Uzbek, Turkmen, Brahui, Balochi, Hazaragi Albania Tosk Albanian, Gheg Albanian, Macedo-Romanian, Greek, Vlax Romani Algeria Arabic (official), French, Kabyle, Chaouia American Samoa Samoan, English Andorra Catalán (official), French, Spanish Angola Portuguese (official), Umbundu, Nyemba, Nyaneka, Loanda-Mbundu, Luchazi, Kongo, Chokwe Anguilla English (official), Anguillan Creole English Antigua and Barbuda English (official), Antigua Creole English, Barbuda Creole English Argentina Spanish (official), Pampa, English, Italian, German, French, Guaraní, Araucano, Quechua Armenia Armenian, Russian, North Azerbaijani -

The United States Virgin Islands 8 Tyler B

The United States Virgin Islands 8 Tyler B. Smith, Marilyn E. Brandt, Viktor W. Brandtneris, Rosmin S. Ennis, Sarah H. Groves, Sennai Habtes, Daniel M. Holstein, Elizabeth Kadison, and Richard S. Nemeth Abstract (45–151 species), but often their biomass is dominated by Mesophotic coral ecosystems (MCEs) at 30–100 m depth a few species, particularly on edges with high abundances are the dominant hard bottom habitat in the US Virgin of planktivores and piscivores. Despite their importance to Islands of the northeastern Caribbean Sea. Well-developed the ecology and economy of USVI, MCEs are threatened MCEs surpass the extent of shallow coral reefs by almost by a variety of local and global stressors and disturbances a factor of three. These habitats range from high coral that are causing declines in coral cover. cover structural reefs to low coral cover hard bottoms on banks, slopes, and walls. The most common communities Keywords in the United States Virgin Islands (USVI) are star coral Mesophotic coral ecosystems · Orbicella banks · (Orbicella franksi) banks that are concentrated in a rela- Agaricia fringe · Fish spawning aggregations · tively large area (187 km2) south and southwest of St. Disturbance Thomas in depths of 30–43 m. Wall and slope coral com- munities in upper (30–60 m) and lower MCE (60–100 m) depths are dominated by lettuce corals (Agaricia spp.) Most MCEs are heavily covered in macroalgae, particu- 8.1 Introduction larly Lobophora variegata. Corals are species rich in many upper MCE habitats (20–28 species) compared with shal- Caribbean mesophotic coral ecosystems (MCEs) are hard low reefs (31), but not in upper and lower MCE slopes and bottom habitats containing or dominated by scleractinian walls (6–8). -

British Virgin Islands Information

British Virgin Islands Information General Information Area: 59 sq miles (153 sq km) Population: 18,000 Capital city: Road Town on Tortola Language: English Government: British Dependent Territory Currency: The Local currency is the United States Dollar (USD) Electricity: The voltage used is 110-120 Volts (Same as U.S./Canada) Time: UTC/GMT -4 hours. Tourist Information Centre Road Town, Tortola, BVI Tel: (284) 494-3134 Fax: (284) 494-3866 E-mail: [email protected] Arrival & Departure Two ways to get to Tortola: Fly to Tortola’s Beef Island Airport; take taxi to the base. Fly to St. Thomas and take the Roadtown Fast Ferry into Roadtown Harbour, Tortola. Customs & Immigration A valid passport (for each passenger) and crew list is compulsory for clearance. Expiration date must be no earlier than 6 months after your planned return. A customs declaration form must be completed at the port of entry. IMPORTANT: Signature and Bareboat charters with a hired crew, that intend to visit either the US or Spanish Virgin Islands, need to advise the Moorings Vacation Planning department to advice accordingly. Airport-Located at Beef Island Airport Transfers Beef Island Airport to Roadtown Distance is approximately 30 minutes by taxi. For your convenience, you may purchase round-trip tickets for Beef Island Airport transfers in advance of your charter. St. Thomas to Roadtown For your convenience, you may purchase your ferry tickets or a combination of ferry/taxi tickets in advance of your charter. The distance is approximately 60 min by ferry transfer. Please contact our Vacation Planning Team for more details regarding both available options. -

On the Water the Moorings Company Journey

UNFORGETTABLE MOMENTS 2017 PRESS KIT on the water The Moorings Company Journey ON FOURTH OF JULY WEEKEND, THE MOORINGS BEGINS A partnership OPERATIONS IN TORTOLA, BRITISH VIRGIN ISLANDS. is formed with WITH SIX 35-FOOT PEARSON YACHTS, CHARLIE AND GINNY catamaran yacht CARY PIONEER YACHT CHARTERING IN THE BVI. builders Robertson Along with his wife Ginny, Charlie moved from New Orleans to the British & Caine. The first Virgin Islands to start a small boat rental operation called The Moorings, catamarans are offering travelers a new and unique way to explore the islands and added to the fleet – experience the thrill of sailing. The Carys worked tirelessly to make this the Moorings 4500 new concept a success, caring for each customer like family. and the Moorings The Moorings The company begins 3800. The Moorings Soon enough, The Moorings started to grow. Charlie and Ginny expanded expands into the its expansion into the 4500 is named “Best their fleet and hired staff from the local community to help carry the lower Caribbean with Mediterranean with Charter Boat” by company into the future. a base in Marigot Bay, charter offerings in Cruising World St. Lucia. Greece. Magazine. 1969 1981 1989 1997 2 2017 Press Kit View complete Timeline The Moorings expands The Moorings completes further into the a $15 million expansion Mediterranean and with the grand re-opening The Moorings new The Moorings debuts the Exotics with destinations of the BVI flagship flagship 4800 Catamaran 433 Power catamaran in in the Grenadines; charter base, and the is introduced for bareboat the BVI and the Bahamas. -

Snorkeling, Sailing and Fishing As Well

THE BEST OF 1 PUERTO RICO t’s only the size of Connecticut, but Puerto Rico pulsates with more life than any other island in the Caribbean. IWhether it’s the beat of bomba y plena, salsa, or reggae- ton, there’s a party going on here 24/7. The four million people who live here have perfected the art of having fun on their dazzling island, and visitors are free to join right in. Puerto Ricans love their island and take pride in showing off its charms, which makes them among the world’s great hosts. Especially on weekends, there seems to be something going on just about everywhere—whether it’s an art fair in Old San Juan, a pig roast in the rural mountain area outside town, or a volleyball competition or free concert on the beach in Isla Verde. More so than on any other island, visitors are more likely to rub elbows with locals in Puerto Rico because so many of them are out enjoying themselves. For island hotels and restaurants, local residents are an important and loyal part of their clientele. Puerto Rico is blessed with towering mountains, rainforests, white sandy beaches along Caribbean shores, and a vibrant culture forged from a mix of Caribbean, Hispanic, African, and U.S. influences. Culture vultures will find a wealth of historic buildings and monuments, many of them dating back some 500 years to the Spanish conquistadors. There are three world-class museums and a thriving gallery scene in San Juan. The city is more intimate but just as exciting as Miami or Las Vegas, and the sophisticated fashion sense of the city and its inhabitants will genu- inely impress visitors. -

Puerto-Rico-Frommers.Pdf

01_257111 ffirs.qxp 8/25/08 11:21 PM Page i Puerto Rico 9th Edition by John Marino Here’s what the critics say about Frommer’s: “Amazingly easy to use. Very portable, very complete.” —Booklist “Detailed, accurate, and easy-to-read information for all price ranges.” —Glamour Magazine “Hotel information is close to encyclopedic.” —Des Moines Sunday Register “Frommer’s Guides have a way of giving you a real feel for a place.” —Knight Ridder Newspapers 02_257111 ftoc.qxp 8/25/08 11:22 PM Page vi 01_257111 ffirs.qxp 8/25/08 11:21 PM Page i Puerto Rico 9th Edition by John Marino Here’s what the critics say about Frommer’s: “Amazingly easy to use. Very portable, very complete.” —Booklist “Detailed, accurate, and easy-to-read information for all price ranges.” —Glamour Magazine “Hotel information is close to encyclopedic.” —Des Moines Sunday Register “Frommer’s Guides have a way of giving you a real feel for a place.” —Knight Ridder Newspapers 01_257111 ffirs.qxp 8/25/08 11:21 PM Page ii About the Author John Marino is editor of the The San Juan Star and has written about Puerto Rico and the Caribbean for Reuters, The Washington Post, The New York Times, Gourmet, and other publications. He lives in San Juan, Puerto Rico with his wife Jova and son Juan Antonio, who both provided valuable research and insight for this book. Published by: Wiley Publishing, Inc. 111 River St. Hoboken, NJ 07030-5774 Copyright ©2008 Wiley Publishing, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except as permitted under Sections 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authoriza- tion through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, 978/750-8400, fax 978/646-8600. -

Welcome Packet Post Irma

www.villasvirgingorda.com Tel: (284) 540-8002 Welcome to Virgin Gorda! Congratulations! You are among the chosen few who have stumbled upon Nature’s Little Secret, 8 square miles of paradise! Villas Virgin Gorda has been operating on Virgin Gorda for over 14 years. We specialize in the property management of the beautiful homes in our care and in vacation rentals of the properties. We are extremely honored that you have chosen us to provide you with a home during your holiday on Virgin Gorda and we are committed to making sure you are comfortable during your stay. We love everything about Virgin Gorda! We love sailing up to the island and the vista of the mountains rising out of the sea. Of course, the beaches, sailing, and snorkeling are amazing and The Baths are a must visit, but we have also enjoyed exploring the old Copper Mine ruins, hiking the peaks, and lingering over a painkiller at Hog Heaven while enjoying the views of the boats in the North Sound. The local population is made up of amazingly generous and happy people, we challenge you not to make a friend for life on VG! Also take time to enjoy the natural beauty of the island: note the hummingbirds flitting from flower to flower, the lizards running up a wall or tree, the goats hopping on the boulders by the beach, and the chickens leading their chicks through the trees along the shore or just down the main road. Stargazing is another favorite pastime with skies dark enough to see thousands of celestial bodies, shooting stars, and the occasional passing satellite.