Selecting Flux for Soldering Coilcraft Components

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glossary Physics (I-Introduction)

1 Glossary Physics (I-introduction) - Efficiency: The percent of the work put into a machine that is converted into useful work output; = work done / energy used [-]. = eta In machines: The work output of any machine cannot exceed the work input (<=100%); in an ideal machine, where no energy is transformed into heat: work(input) = work(output), =100%. Energy: The property of a system that enables it to do work. Conservation o. E.: Energy cannot be created or destroyed; it may be transformed from one form into another, but the total amount of energy never changes. Equilibrium: The state of an object when not acted upon by a net force or net torque; an object in equilibrium may be at rest or moving at uniform velocity - not accelerating. Mechanical E.: The state of an object or system of objects for which any impressed forces cancels to zero and no acceleration occurs. Dynamic E.: Object is moving without experiencing acceleration. Static E.: Object is at rest.F Force: The influence that can cause an object to be accelerated or retarded; is always in the direction of the net force, hence a vector quantity; the four elementary forces are: Electromagnetic F.: Is an attraction or repulsion G, gravit. const.6.672E-11[Nm2/kg2] between electric charges: d, distance [m] 2 2 2 2 F = 1/(40) (q1q2/d ) [(CC/m )(Nm /C )] = [N] m,M, mass [kg] Gravitational F.: Is a mutual attraction between all masses: q, charge [As] [C] 2 2 2 2 F = GmM/d [Nm /kg kg 1/m ] = [N] 0, dielectric constant Strong F.: (nuclear force) Acts within the nuclei of atoms: 8.854E-12 [C2/Nm2] [F/m] 2 2 2 2 2 F = 1/(40) (e /d ) [(CC/m )(Nm /C )] = [N] , 3.14 [-] Weak F.: Manifests itself in special reactions among elementary e, 1.60210 E-19 [As] [C] particles, such as the reaction that occur in radioactive decay. -

Light and Illumination

ChapterChapter 3333 -- LightLight andand IlluminationIllumination AAA PowerPointPowerPointPowerPoint PresentationPresentationPresentation bybyby PaulPaulPaul E.E.E. Tippens,Tippens,Tippens, ProfessorProfessorProfessor ofofof PhysicsPhysicsPhysics SouthernSouthernSouthern PolytechnicPolytechnicPolytechnic StateStateState UniversityUniversityUniversity © 2007 Objectives:Objectives: AfterAfter completingcompleting thisthis module,module, youyou shouldshould bebe ableable to:to: •• DefineDefine lightlight,, discussdiscuss itsits properties,properties, andand givegive thethe rangerange ofof wavelengthswavelengths forfor visiblevisible spectrum.spectrum. •• ApplyApply thethe relationshiprelationship betweenbetween frequenciesfrequencies andand wavelengthswavelengths forfor opticaloptical waves.waves. •• DefineDefine andand applyapply thethe conceptsconcepts ofof luminousluminous fluxflux,, luminousluminous intensityintensity,, andand illuminationillumination.. •• SolveSolve problemsproblems similarsimilar toto thosethose presentedpresented inin thisthis module.module. AA BeginningBeginning DefinitionDefinition AllAll objectsobjects areare emittingemitting andand absorbingabsorbing EMEM radiaradia-- tiontion.. ConsiderConsider aa pokerpoker placedplaced inin aa fire.fire. AsAs heatingheating occurs,occurs, thethe 1 emittedemitted EMEM waveswaves havehave 2 higherhigher energyenergy andand 3 eventuallyeventually becomebecome visible.visible. 4 FirstFirst redred .. .. .. thenthen white.white. LightLightLight maymaymay bebebe defineddefineddefined -

Black Body Radiation and Radiometric Parameters

Black Body Radiation and Radiometric Parameters: All materials absorb and emit radiation to some extent. A blackbody is an idealization of how materials emit and absorb radiation. It can be used as a reference for real source properties. An ideal blackbody absorbs all incident radiation and does not reflect. This is true at all wavelengths and angles of incidence. Thermodynamic principals dictates that the BB must also radiate at all ’s and angles. The basic properties of a BB can be summarized as: 1. Perfect absorber/emitter at all ’s and angles of emission/incidence. Cavity BB 2. The total radiant energy emitted is only a function of the BB temperature. 3. Emits the maximum possible radiant energy from a body at a given temperature. 4. The BB radiation field does not depend on the shape of the cavity. The radiation field must be homogeneous and isotropic. T If the radiation going from a BB of one shape to another (both at the same T) were different it would cause a cooling or heating of one or the other cavity. This would violate the 1st Law of Thermodynamics. T T A B Radiometric Parameters: 1. Solid Angle dA d r 2 where dA is the surface area of a segment of a sphere surrounding a point. r d A r is the distance from the point on the source to the sphere. The solid angle looks like a cone with a spherical cap. z r d r r sind y r sin x An element of area of a sphere 2 dA rsin d d Therefore dd sin d The full solid angle surrounding a point source is: 2 dd sind 00 2cos 0 4 Or integrating to other angles < : 21cos The unit of solid angle is steradian. -

Multidisciplinary Design Project Engineering Dictionary Version 0.0.2

Multidisciplinary Design Project Engineering Dictionary Version 0.0.2 February 15, 2006 . DRAFT Cambridge-MIT Institute Multidisciplinary Design Project This Dictionary/Glossary of Engineering terms has been compiled to compliment the work developed as part of the Multi-disciplinary Design Project (MDP), which is a programme to develop teaching material and kits to aid the running of mechtronics projects in Universities and Schools. The project is being carried out with support from the Cambridge-MIT Institute undergraduate teaching programe. For more information about the project please visit the MDP website at http://www-mdp.eng.cam.ac.uk or contact Dr. Peter Long Prof. Alex Slocum Cambridge University Engineering Department Massachusetts Institute of Technology Trumpington Street, 77 Massachusetts Ave. Cambridge. Cambridge MA 02139-4307 CB2 1PZ. USA e-mail: [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] tel: +44 (0) 1223 332779 tel: +1 617 253 0012 For information about the CMI initiative please see Cambridge-MIT Institute website :- http://www.cambridge-mit.org CMI CMI, University of Cambridge Massachusetts Institute of Technology 10 Miller’s Yard, 77 Massachusetts Ave. Mill Lane, Cambridge MA 02139-4307 Cambridge. CB2 1RQ. USA tel: +44 (0) 1223 327207 tel. +1 617 253 7732 fax: +44 (0) 1223 765891 fax. +1 617 258 8539 . DRAFT 2 CMI-MDP Programme 1 Introduction This dictionary/glossary has not been developed as a definative work but as a useful reference book for engi- neering students to search when looking for the meaning of a word/phrase. It has been compiled from a number of existing glossaries together with a number of local additions. -

STHF-R Ultra High Flux Gamma Probe Data Sheet

Features STHF-R™ Ultra High ■ Measurement of H*(10) Flux Gamma Probe ambient gamma dose equivalent rate up to 1000 Sv/h (100 000 R/h) Description ■ To be connected to The STHF-R ultra high flux Radiagem™, MIP 10 Digital™ probe is designed for the or Avior ® meters measurements of very high ■ Waterproof: 80 m (262.5 ft) gamma dose-equivalent rates water depth up to 1000 Sv/h. ■ Detector: Silicon diode This probe is especially ■ 5 kSv maximum integrated designed for ultra high flux dose measurement which can be found in pools in nuclear ■ Compact portable design for power plants or in recycling detector and detector cable facilities. Effectively this on reel probes box is stainless steel based and waterproof up to 80 m (164 ft) underwater. It can be laid underwater in the storage pools Borated water. An optional ballast weight can be supplied to ease underwater measurements. The STHF-R probe is composed of two matched units: ■ The measurement probe including the silicon diode and the associated analog electronics. ■ An interface case which houses the processing electronics that are more sensitive to radiation; this module can be remotely located up to 50 m (164 ft) from the measurement spot. ■ An intermediate connection point with 50 m length cable to which the interface case can be connected. The STHF-R probe can be connected directly to Avior, Radiagem or MIP 10 Digital meters. The STHF-R unit receives power from the survey meter during operation. STHF-R instruments include key components of hardware circuitry (high voltage power supply, amplifier, discriminator, etc.). -

LFC-050-LE Light Flux Color and Luminous Efficacy Measurement Systems Why Choose Lightfluxcolor

LFC-050-LE Light Flux Color and Luminous Efficacy Measurement Systems Why Choose LightFluxColor • Calibrations are traceable to NIST (USA) which are accepted and recognized globally. Ideal For Flux, Color & AC/DC The most economical and • Calibrated lamp standards NVLAP Electrical Characterization of: reliable solution for photometry accreditation Lab Code 200951-0 of light source needs! Automotive Lamps Traffic Lighting (ISO 17025) LED Clusters Architectural Lighting • Spectral flux standards (calibration LightFluxColor-LE Series Systems are the performed at each wavelength) are LED Bulbs Railway Lighting most affordable and reliable systems for testing supplied with each system for highest LED lighting products. Whether you are a possible accuracy. manufacturer of LED luminaires, street lights, • Single software controls all electronics and solar powered LED lanterns, LED bulbs, LightFluxColor-LE Series Systems also include provides optical and electrical data. or any other type of LED lighting product, a highly sensitive mini-calibrated CCD Array Spectrometer with spectral range from LightFluxColor Systems will meet all your testing • Competitive systems only provide 250 to 850 nm. This low noise and broad spectral requirements. LightFluxColor Systems allow luminous flux standards with CCT luminaire manufacturers to test LED products response spectrometer provide instantaneous calibration which limits overall for photometric performance. measurement of radiometric, photometric, and system accuracy. color characteristics of the LED sources. • AC/DC operation in one packaged LightFluxColor-LE Series Systems allow testing system users to test AC/DC characterization of lamps The fast results from the spectrometer helps at various input frequencies along with lumens to increase the rate of product development, • An auxiliary lamp is provided for and color parameters. -

Radiometry of Light Emitting Diodes Table of Contents

TECHNICAL GUIDE THE RADIOMETRY OF LIGHT EMITTING DIODES TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 Introduction . .1 2.0 What is an LED? . .1 2.1 Device Physics and Package Design . .1 2.2 Electrical Properties . .3 2.2.1 Operation at Constant Current . .3 2.2.2 Modulated or Multiplexed Operation . .3 2.2.3 Single-Shot Operation . .3 3.0 Optical Characteristics of LEDs . .3 3.1 Spectral Properties of Light Emitting Diodes . .3 3.2 Comparison of Photometers and Spectroradiometers . .5 3.3 Color and Dominant Wavelength . .6 3.4 Influence of Temperature on Radiation . .6 4.0 Radiometric and Photopic Measurements . .7 4.1 Luminous and Radiant Intensity . .7 4.2 CIE 127 . .9 4.3 Spatial Distribution Characteristics . .10 4.4 Luminous Flux and Radiant Flux . .11 5.0 Terminology . .12 5.1 Radiometric Quantities . .12 5.2 Photometric Quantities . .12 6.0 References . .13 1.0 INTRODUCTION Almost everyone is familiar with light-emitting diodes (LEDs) from their use as indicator lights and numeric displays on consumer electronic devices. The low output and lack of color options of LEDs limited the technology to these uses for some time. New LED materials and improved production processes have produced bright LEDs in colors throughout the visible spectrum, including white light. With efficacies greater than incandescent (and approaching that of fluorescent lamps) along with their durability, small size, and light weight, LEDs are finding their way into many new applications within the lighting community. These new applications have placed increasingly stringent demands on the optical characterization of LEDs, which serves as the fundamental baseline for product quality and product design. -

• Flux and Luminosity • Brightness of Stars • Spectrum of Light • Temperature and Color/Spectrum • How the Eye Sees Color

Stars • Flux and luminosity • Brightness of stars • Spectrum of light • Temperature and color/spectrum • How the eye sees color Which is of these part of the Sun is the coolest? A) Core B) Radiative zone C) Convective zone D) Photosphere E) Chromosphere Flux and luminosity • Luminosity - A star produces light – the total amount of energy that a star puts out as light each second is called its Luminosity. • Flux - If we have a light detector (eye, camera, telescope) we can measure the light produced by the star – the total amount of energy intercepted by the detector divided by the area of the detector is called the Flux. Flux and luminosity • To find the luminosity, we take a shell which completely encloses the star and measure all the light passing through the shell • To find the flux, we take our detector at some particular distance from the star and measure the light passing only through the detector. How bright a star looks to us is determined by its flux, not its luminosity. Brightness = Flux. Flux and luminosity • Flux decreases as we get farther from the star – like 1/distance2 • Mathematically, if we have two stars A and B Flux Luminosity Distance 2 A = A B Flux B Luminosity B Distance A Distance-Luminosity relation: Which star appears brighter to the observer? Star B 2L L d Star A 2d Flux and luminosity Luminosity A Distance B 1 =2 = LuminosityB Distance A 2 Flux Luminosity Distance 2 A = A B Flux B Luminosity B DistanceA 1 2 1 1 =2 =2 = Flux = 2×Flux 2 4 2 B A Brightness of stars • Ptolemy (150 A.D.) grouped stars into 6 `magnitude’ groups according to how bright they looked to his eye. -

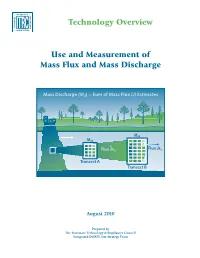

Use and Measurement of Mass Flux and Mass Discharge

Technology Overview Use and Measurement of Mass Flux and Mass Discharge Mass Discharge (Md) = Sum of Mass Flux (J) Estimates MdB MdA B Flux JAi,j Flux J i,j Transect A Transect B August 2010 Prepared by The Interstate Technology & Regulatory Council Integrated DNAPL Site Strategy Team ABOUT ITRC Established in 1995, the Interstate Technology & Regulatory Council (ITRC) is a state-led, national coalition of personnel from the environmental regulatory agencies of all 50 states and the District of Columbia, three federal agencies, tribes, and public and industry stakeholders. The organization is devoted to reducing barriers to, and speeding interstate deployment of, better, more cost-effective, innovative environmental techniques. ITRC operates as a committee of the Environmental Research Institute of the States (ERIS), a Section 501(c)(3) public charity that supports the Environmental Council of the States (ECOS) through its educational and research activities aimed at improving the environment in the United States and providing a forum for state environmental policy makers. More information about ITRC and its available products and services can be found on the Internet at www.itrcweb.org. DISCLAIMER ITRC documents and training are products designed to help regulators and others develop a consistent approach to their evaluation, regulatory approval, and deployment of specific technologies at specific sites. Although the information in all ITRC products is believed to be reliable and accurate, the product and all material set forth within are provided without warranties of any kind, either express or implied, including but not limited to warranties of the accuracy or completeness of information contained in the product or the suitability of the information contained in the product for any particular purpose. -

GLAST Science Glossary (PDF)

GLAST SCIENCE GLOSSARY Source: http://glast.sonoma.edu/science/gru/glossary.html Accretion — The process whereby a compact object such as a black hole or neutron star captures matter from a normal star or diffuse cloud. Active galactic nuclei (AGN) — The central region of some galaxies that appears as an extremely luminous point-like source of radiation. They are powered by supermassive black holes accreting nearby matter. Annihilation — The process whereby a particle and its antimatter counterpart interact, converting their mass into energy according to Einstein’s famous formula E = mc2. For example, the annihilation of an electron and positron results in the emission of two gamma-ray photons, each with an energy of 511 keV. Anticoincidence Detector — A system on a gamma-ray observatory that triggers when it detects an incoming charged particle (cosmic ray) so that the telescope will not mistake it for a gamma ray. Antimatter — A form of matter identical to atomic matter, but with the opposite electric charge. Arcminute — One-sixtieth of a degree on the sky. Like latitude and longitude on Earth's surface, we measure positions on the sky in angles. A semicircle that extends up across the sky from the eastern horizon to the western horizon is 180 degrees. One degree, therefore, is not a very big angle. An arcminute is an even smaller angle, 1/60 as large as a degree. The Moon and Sun are each about half a degree across, or about 30 arcminutes. If you take a sharp pencil and hold it at arm's length, then the point of that pencil as seen from your eye is about 3 arcminutes across. -

Radiometry and Photometry

Radiometry and Photometry Wei-Chih Wang Department of Power Mechanical Engineering National TsingHua University W. Wang Materials Covered • Radiometry - Radiant Flux - Radiant Intensity - Irradiance - Radiance • Photometry - luminous Flux - luminous Intensity - Illuminance - luminance Conversion from radiometric and photometric W. Wang Radiometry Radiometry is the detection and measurement of light waves in the optical portion of the electromagnetic spectrum which is further divided into ultraviolet, visible, and infrared light. Example of a typical radiometer 3 W. Wang Photometry All light measurement is considered radiometry with photometry being a special subset of radiometry weighted for a typical human eye response. Example of a typical photometer 4 W. Wang Human Eyes Figure shows a schematic illustration of the human eye (Encyclopedia Britannica, 1994). The inside of the eyeball is clad by the retina, which is the light-sensitive part of the eye. The illustration also shows the fovea, a cone-rich central region of the retina which affords the high acuteness of central vision. Figure also shows the cell structure of the retina including the light-sensitive rod cells and cone cells. Also shown are the ganglion cells and nerve fibers that transmit the visual information to the brain. Rod cells are more abundant and more light sensitive than cone cells. Rods are 5 sensitive over the entire visible spectrum. W. Wang There are three types of cone cells, namely cone cells sensitive in the red, green, and blue spectral range. The approximate spectral sensitivity functions of the rods and three types or cones are shown in the figure above 6 W. Wang Eye sensitivity function The conversion between radiometric and photometric units is provided by the luminous efficiency function or eye sensitivity function, V(λ). -

Transmittance Four-Up

Transmittance notes Transmittance notes – cont I What is the difference between transmittance and transmissivity? There really isn’t any: see the AMS glossary entry I Review: prove that the total transmittance for two layers is I Review the relationship between the transmittance, absorption Trtot = Tr1 Tr2: cross section, flux and radiance × I Introduce the optical depth, τλ and the differential F2 transmissivity, dTr = dτλ Trtot = − F0 I Show that Fλ = Fλ0 exp( τλ) for “direct beam” flux − F1 Tr1 = F0 F2 F2 Tr2 = = F1 Tr1F0 F2 Tr1Tr2 = = Trtot F0 Transmittance 1/10 Transmittance 2/10 scattering and absorption cross section flux and itensity I Since we know that we are dealing with flux in a very small I Beer’s law for flux absorption comes from Maxwell’s equations: solid angle, we can divide (1) through by ∆ω, recogize that Iλ Fλ/∆ω in this near-parallel beam case and get Beer’s Fλ = Fλ0exp( βas) (1) ≈ − law for intensity: 2 3 where βa m m− is the volume absorption coefficient. 2 We are ignoring the spherical spreading (1/r ) loss in (1) Iλ = Iλ0exp( βas) (2) under the assumption that the source is very far way, so that − I Take the differential of either (1) or (2) and get something s, the distance traveled, is much much smaller than r, the like this: distance from the source. I This limits the applicability of (1) to direct sunlight and laser dIλ = βadsIλ0exp( βas) = Iλβads (3) light. − − − or I The assumption that the source is far away is the same as assuming that it occupies a very small solid angle ∆ω.