Pages 68-138 (Survey)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

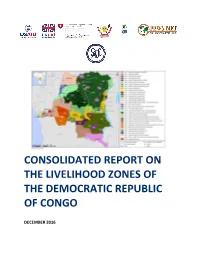

DRC Consolidated Zoning Report

CONSOLIDATED REPORT ON THE LIVELIHOOD ZONES OF THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO DECEMBER 2016 Contents ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ......................................................................................... 5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .......................................................................................................... 6 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................ 7 1.1 Livelihoods zoning ....................................................................................................................7 1.2 Implementation of the livelihood zoning ...................................................................................8 2. RURAL LIVELIHOODS IN DRC - AN OVERVIEW .................................................................. 11 2.1 The geographical context ........................................................................................................ 11 2.2 The shared context of the livelihood zones ............................................................................. 14 2.3 Food security questions ......................................................................................................... 16 3. SUMMARY DESCRIPTIONS OF THE LIVELIHOOD ZONES .................................................... 18 CD01 COPPERBELT AND MARGINAL AGRICULTURE ....................................................................... 18 CD01: Seasonal calendar .................................................................................................................... -

Report Reflects the Views of the Authors and Can in No Way Be Taken to Reflect the Views of Humanity United

‘Conflict Minerals’ initiatives in DR Congo: Perceptions of local mining communities Ken Matthysen & Andrés Zaragoza Montejano 1 Editorial ‘Conflict Minerals’ initiatives in DR Congo: Perceptions of local mining communities Authors: Ken Matthysen & Andrés Zaragoza Montejano (IPIS) Editing: Fiona Southward, Steven Spittaels, & Anna Bulzomi (IPIS); Frédéric Triest (EurAc); Chantal Daniels (Christian Aid); Zobel Behalal (CCFD); Koen Warmenbol (11.11.11.) Layout: Anne Hullebroeck Front Cover image: Artisanal miners working in Kalimbi mine, near Nyabibwe (IPIS, April 2013) Antwerp, November2013 Acknowledgements: This project has been made possible through the support of Humanity United. The report reflects the views of the authors and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of Humanity United. The report has been developed in cooperation with the European Network for Central Africa (EurAc). 2 Executive Summary The exploitation of minerals is an important source of income for many communities in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Yet this mineral wealth also plays a significant role in the continuation of insecurity in parts of the country. Revenues from mineral trade have given armed groups the means to operate, and provided off-budget funding to (often poorly paid) state security forces. Whilst recognising that this mineral wealth is not one of the root-causes of conflict, their trade does play a central role in funding and fuelling conflicts in the DRC, further weakening the already fragile government. Over recent years, several domestic, regional and international initiatives have been developed to address the so-called ‘conflict minerals’ problem and the high level of informality in the DRC’s artisanal mining sector. -

Consolidated Report on the Livelihood Zones of the Democratic Republic

CONSOLIDATED REPORT ON THE LIVELIHOOD ZONES OF THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO DECEMBER 2016 Contents ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ......................................................................................... 5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .......................................................................................................... 6 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................ 7 1.1 Livelihoods zoning ....................................................................................................................7 1.2 Implementation of the livelihood zoning ...................................................................................8 2. RURAL LIVELIHOODS IN DRC - AN OVERVIEW .................................................................. 11 2.1 The geographical context ........................................................................................................ 11 2.2 The shared context of the livelihood zones ............................................................................. 14 2.3 Food security questions ......................................................................................................... 16 3. SUMMARY DESCRIPTIONS OF THE LIVELIHOOD ZONES .................................................... 18 CD01 COPPERBELT AND MARGINAL AGRICULTURE ....................................................................... 18 CD01: Seasonal calendar .................................................................................................................... -

The Complexity of Resource Governance in a Context of State Fragility: an Analysis of the Mining Sector in the Kivu Hinterlands

The complexiTy of resource governance in a conTexT of sTaTe fragiliTy: an analysis of The mining secTor in The Kivu hinTerlands steven spittaels november 2010 this initiative is funded Understanding conflict. Building peace. by the european union about international alert international alert is an independent peacebuilding organisation that has worked for over 20 years to lay the foundations for lasting peace and security in communities affected by violent conflict. our multifaceted approach focuses both in and across various regions; aiming to shape policies and practices that affect peacebuilding; and helping build skills and capacity through training. our field work is based in africa, south asia, the south Caucasus, Latin america, Lebanon and the philippines. our thematic projects work at local, regional and international levels, focusing on cross- cutting issues critical to building sustainable peace. these include business and economy, gender, governance, aid, security and justice. We are one of the world’s leading peacebuilding nGos with more than 125 staff based in London and our 13 field offices.t o learn more, visit www.international-alert.org. this research is funded by the european union. its contents are the sole responsibility of international alert and can in no way be regarded as reflecting the point of view of the european union. about ipis IPIS seeks to be a key reference worldwide for all information related to our three core themes of research: arms trade, the exploitation of natural resources and corporate social responsibility in sub-saharan africa. in order to enhance our reputation as a necessary and independent source of information, we aim at two objectives: to expand our unique field expertise which distinguishes us from other research institutes; to observe the highest quality standards for the output of our research. -

'Conflict Minerals' Initiatives in DR Congo

‘Conflict Minerals’ initiatives in DR Congo: Perceptions of local mining communities Ken Matthysen & Andrés Zaragoza Montejano 1 Editorial ‘Conflict Minerals’ initiatives in DR Congo: Perceptions of local mining communities Authors: Ken Matthysen & Andrés Zaragoza Montejano (IPIS) Editing: Fiona Southward, Steven Spittaels, & Anna Bulzomi (IPIS); Frédéric Triest (EurAc); Chantal Daniels (Christian Aid); Zobel Behalal (CCFD); Koen Warmenbol (11.11.11.) Layout: Anne Hullebroeck Front Cover image: Artisanal miners working in Kalimbi mine, near Nyabibwe (IPIS, April 2013) Antwerp, November 2013 Acknowledgements: This project has been made possible through the support of Humanity United. The report reflects the views of the authors and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of Humanity United. The report has been developed in cooperation with the European Network for Central Africa (EurAc). 2 Executive Summary The exploitation of minerals is an important source of income for many communities in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Yet this mineral wealth also plays a significant role in the continuation of insecurity in parts of the country. Revenues from mineral trade have given armed groups the means to operate, and provided off-budget funding to (often poorly paid) state security forces. Whilst recognising that this mineral wealth is not one of the root-causes of conflict, their trade does play a central role in funding and fuelling conflicts in the DRC, further weakening the already fragile government. Over recent years, several domestic, regional and international initiatives have been developed to address the so-called ‘conflict minerals’ problem and the high level of informality in the DRC’s artisanal mining sector. -

Elixir Journal

53303 Tambwe Kasongo Henoc et al./ Elixir Agriculture 132 (2019) 53303-53307 Available online at www.elixirpublishers.com (Elixir International Journal) Agriculture Elixir Agriculture 132 (2019) 53303-53307 Morphological Diversity of Banana and Plantain in the Province of Maniema in DR Congo Tambwe Kasongo Henoc1, Solia Edondoto Sylvain2, Okungo Lotokola Albert2 and Dhed'a Djailo Benoit3 1University of Kindu, Faculty of Agricultural Sciences, Site Lwama 1, 2Institut Faculty of Agricultural Sciences of Yangambi, Laboratory of Ecophysiology and Plant Nutrition, 750/9/6 Munyororo Avenue, Medical Plateau District, B.P 1232 Kisangani. 3Kisangani University, Laboratory of Genetics, Plant Breeding and Biotechnology.Faculty of Science, B.P 2012 Kisangani. ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: The purpose of this study was to determine the morphological diversity of banana and Received: 24 May 2019; plantain in the province of Maniema and to identify criteria for the choice of planting Received in revised form: material, as well as the different uses of banana in the study area. To do this, a survey 20 June 2019; was carried out using the questionnaire established by Bioversity-CIALCA, on the Accepted: 1 July 2019; morphological characterization of the different cultivars. These surveys identified 19 banana cultivars as follows: 4 French type plantains, 3 false horns, 2 true horns, 6 dessert Keywords bananas and 4 cooking plantains not belonging to the first three groups. The results also Morphological diversity, showed that dessert-type bananas are the most diversified in the study area (Maniema Cultivars, Province) with a proportion of 31% followed by French-type plantains with 27%. A Banana and plantain, small proportion of cooking plantains (7%) were recorded in this region. -

An Analysis of the Mining Sector in the Kivu Hinterlands

The complexiTy of resource governance in a conTexT of sTaTe fragiliTy: an analysis of The mining secTor in The Kivu hinTerlands steven spittaels (ed.) november 2010 this initiative is funded Understanding conflict. Building peace. by the european union about international alert international alert is an independent peacebuilding organisation that has worked for over 20 years to lay the foundations for lasting peace and security in communities affected by violent conflict. our multifaceted approach focuses both in and across various regions; aiming to shape policies and practices that affect peacebuilding; and helping build skills and capacity through training. our field work is based in africa, south asia, the south Caucasus, Latin america, Lebanon and the philippines. our thematic projects work at local, regional and international levels, focusing on cross- cutting issues critical to building sustainable peace. these include business and economy, gender, governance, aid, security and justice. We are one of the world’s leading peacebuilding nGos with more than 125 staff based in London and our 13 field offices.t o learn more, visit www.international-alert.org. this research is funded by the european union. its contents are the sole responsibility of international alert and can in no way be regarded as reflecting the point of view of the european union. about ipis IPIS seeks to be a key reference worldwide for all information related to our three core themes of research: arms trade, the exploitation of natural resources and corporate social responsibility in sub-saharan africa. in order to enhance our reputation as a necessary and independent source of information, we aim at two objectives: to expand our unique field expertise which distinguishes us from other research institutes; to observe the highest quality standards for the output of our research. -

Mapping Artisanal Mining Areas and Mineral Supply Chains in Eastern DR Congo Impact of Armed Interference & Responsible Sourcing

Mapping artisanal mining areas and mineral supply chains in eastern DR Congo Impact of armed interference & responsible sourcing International Peace Information Service vzw EDITORIAL Mapping artisanal mining areas and mineral supply chains in Eastern DR Congo Impact of armed interference & responsible sourcing Antwerp, April 2019 Cover image: Gold Mine in Kalehe, South Kivu (Photo: IPIS) Authors: Ken Matthysen (IPIS), Steven Spittaels (IPIS associate researcher), Peer Schouten (DIIS) Coordinator field research: Zacharie Bulakali Ntakobajira Map, database and graphs: Manuel Claeys Bouuaert, Stef Verheyen The International Peace Information Service (IPIS) is an independent research institute providing tailored information, analysis and capacity enhancement to support those actors who want to realize a vision of durable peace, sustainable development and the fulfilment of human rights. The Danish Institute for International Studies (DIIS) is an independent research institute that pro- vides analysis of international politics. The research is organized around a large number of programs that cover topics ranging from natural resources and the environment, to terrorism and migration. The 2016-2018 mapping of artisanal mining sites in eastern DRC was funded by the International Or- ganization for Migration- IOM in the DRC through the United States Agency for International Develop- ment-USAID funded Responsible Minerals Trade (RMT) project. Case studies were funded through a Conflict Research Fellowship of the SSRC for the LSE-based Conflict Research -

Analysis of the Interactive Map of Artisanal Mining Areas in Eastern DR Congo: May 2014 Update

Analysis of the interactive map of artisanal mining areas in Eastern DR Congo: May 2014 update 1 Editorial Analysis of the interactive map of artisanal mining areas in Eastern DR Congo: May 2014 update IPIS dedicates this report to Germain Bikuba Assani, who was a diligent collaborator and a valued friend. Authors: Steven Spittaels, Ken Matthysen, Yannick Weyns, Filip Hilgert & Anna Bulzomi Map: Filip Hilgert, Alexandre Jaillon & Stef Verheijen Language edit: Santosh Tymms Layout: Anne Hullebroeck Front Cover image: Screenshot of the interactive webmap of artisanal mining areas in Eastern DR Congo (IPIS 2014) Antwerp, May 2014 The mapping of artisanal mining sites in Eastern DRC was funded by PROMINES, a project sponsored by the World Bank and DFID, and the Federal Public Service Foreign Affairs of Belgium. The analysis of the map was funded by the Belgian Development Cooperation (DGD). The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of IPIS and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of PROMINES or the Belgian government. 2 Highlights Section 1.1 discusses how the removal of M23 has generated hope that Eastern DRC will finally reach stabilisation, provided that a solution is found for the FDLR. Section 1.2 points out that the groups that are profiting the most from the mining activities have retained (almost) all of their control. In section 2.1 it is argued that the regulated part of the tin mining sector in Eastern DRC has already outgrown the ‘problematic’ part and that the number of remaining supply chains of 3T minerals in the Kivu provinces is relatively limited, which should facilitate their future management. -

DRC%20Sitrep%2015%20Oct-23%20Nov%202013.Pdf (Французский (Français))

Monthly humanitarian situation report © UNICEF DRC / © 2013 UNICEF DRC / Morton 15 October - 23 November DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO Highlights Water/Sanitation (p.6) National: On 5 November the M23 movement, a major politico-military force in North Kivu, announced the end of its rebellion. The announcement followed 80,000 successful military operations by the UN-backed Congolese armed forces. people in IDP sites in Irumu covered with WASH interventions Many other armed groups have begun to demand demobilization and reintegra- tion. This potentially important momentum for the peace process as outlined in Education (p.7) the regional Peace and Security Framework (PSF) should be accompanied by a national DDR program, which is still pending approval at the ministerial level. 4,569 National: the Special Representative of the Secretary General for Children in children in 40 schools outside CAR re- fugee camps were given school material Armed Conflict (SRSG-CAAC), Ms. Leila Zerrougui, visited DRC from 18 to 23 November. Accompanied by the UNICEF Representative, she met with many high level officials, civil society organizations, FARDC/PNC and children, raising Health (p.8) important issues of violence against children affected by armed conflict in DRC. 1,761,000 Rutshuru, Nyiragongo: FARDC-led offensives against M23 led to the displace- VAR doses sent to South Kivu ment of 2,500 households in Kanyarucinya and 6,000 in Ntamugenga, Khako and Rutshuru centre. They all returned to their villages soon after FARDC took Nutrition (p.9) control of the areas. Needs assessments by sector started on 13 November in coordination between State and humanitarian actors. -

List of Territories of Democratic Republic of the Congo

SNo Commune or Territory Type City or District Province 1 Aketi Territory Territory Bas-Uele District Orientale 2 Alungili Commune Kindu Maniema 3 Ango Territory Territory Bas-Uele District Orientale 4 Annexe Commune Lubumbashi Katanga 5 Aru Territory Territory Ituri District Orientale 6 Bafwasende Territory Territory Tshopo District Orientale 7 Bagata Territory Territory Kwilu District Bandundu 8 Bagira Commune Bukavu South Kivu 9 Bambesa Territory Territory Bas-Uele District Orientale 10 Banalia Territory Territory Tshopo District Orientale 11 Bandalungwa Commune Funa District Kinshasa 12 Barumbu Commune Lukunga District Kinshasa 13 Basankusu Territory Territory Équateur District Équateur 14 Basoko Territory Territory Tshopo District Orientale 15 Befale Territory Territory Tshuapa District Équateur 16 Beni Territory Territory North Kivu 17 Beni Commune Beni North Kivu 18 Bikoro Territory Territory Équateur District Équateur 19 Bipemba Commune Mbuji-Mayi Kasaï-Oriental 20 Boende Territory Territory Tshuapa District Équateur 21 Bokungu Territory Territory Tshuapa District Équateur 22 Bolobo Territory Territory Plateaux District Bandundu 23 Bolomba Territory Territory Équateur District Équateur 24 Bomongo Territory Territory Équateur District Équateur 25 Bondo Territory Territory Bas-Uele District Orientale 26 Bondoyi Commune Mwene-Ditu Kasaï-Oriental 27 Bongandanga Territory Territory Mongala District Équateur 28 Bosobolo Territory Territory Nord-Ubangi District Équateur 29 Budjala Territory Territory Sud-Ubangi District Équateur 30 Bukama