Essential Characteristics of Lizu, a Qiangic Language of Western Sichuan1 Katia Chirkova (CRLAO, CNRS)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

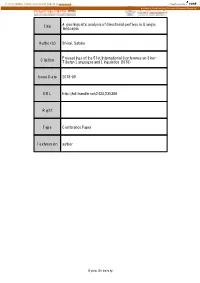

Title a Geolinguistic Analysis of Directional Prefixes In

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kyoto University Research Information Repository A geolinguistic analysis of directional prefixes in Qiangic Title languages Author(s) Shirai, Satoko Proceedings of the 51st International Conference on Sino- Citation Tibetan Languages and Linguistics (2018) Issue Date 2018-09 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/235306 Right Type Conference Paper Textversion author Kyoto University A geolinguistic analysis of directional prefixes in Qiangic languages Satoko Shirai Japan Society for the Promotion of Science/University of Tsukuba 1 Introduction The Qiangic branch of languages are still under discussion with respect to their genealogical details such as its subclassification and position in Tibeto-Burman/Sino-Tibetan languages (Sun 1982, 1983, 2001, 2016; Thurgood 1985; Nishida 1987; Matisoff 2003; Jacques and Michaud 2011; Chirkova 2012). Although it is difficult to find shared phonological innovation in these languages, 1 they share plenty of typological characteristics such as a set of verbal prefixes to indicate the direction of movement (“directional prefixes”). Moreover, certain such typological characteristics including directional prefixes are also found in neighboring languages such as Pema, a Bodic language. This study examines the geographical distribution and relative chronology of representative directional prefixes in Qiangic languages: (i) “upward” (‘UPW’); (ii) “downward” (‘DWN’); (iii) “inward” (‘INW’), “upriver” (‘URV’), “eastward” (‘ES’), and so on; and (iv) “outward” (‘OUT’), “downriver” (‘DRV’), “westward” (‘WS’), and so on.2 Note that I not only examine single morphemes such as in (i) and (ii) but also examine a group of directional prefixes shown in (iii) and (iv), because of their semantic shifts. -

The Qiangic Subgroup from an Areal Perspective: a Case Study of Languages of Muli

LANGUAGE AND LINGUISTICS 13.1:133-170, 2012 2012-0-013-001-000299-1 The Qiangic Subgroup from an Areal Perspective: A Case Study of Languages of Muli Katia Chirkova CRLAO, CNRS In this paper, I study the empirical validity of the hypothesis of “Qiangic” as a subgroup of Sino-Tibetan, that is, the hypothesis of a common origin of thirteen little-studied languages of South-West China. This study is based on ongoing work on four Qiangic languages spoken in one locality (Muli Tibetan Autonomous County, Sichuan), and seen in the context of languages of the neighboring genetic subgroups (Yi, Na, Tibetan, Sinitic). Preliminary results of documentation work cast doubt on the validity of Qiangic as a genetic unit, and suggest instead that features presently seen as probative of the membership in this subgroup are rather the result of diffusion across genetic boundaries. I furthermore argue that the four local languages currently labeled Qiangic are highly distinct and not likely to be closely genetically related. Subsequently, I discuss Qiangic as an areal grouping in terms of its defining characteristics, as well as possible hypotheses pertaining to the genetic affiliation of its member languages currently labeled Qiangic. I conclude with some reflections on the issue of subgrouping in the Qiangic context and in Sino-Tibetan at large. Key words: Qiangic, classification, areal linguistics, Sino-Tibetan 1. Introduction This paper examines the empirical validity of the Qiangic subgrouping hypothesis, as studied in the framework of the project “What defines Qiang-ness: Towards a This is a reworked version of a paper presented at the International Symposium on Sino- Tibetan Comparative Studies in the 21st Century, held at the Institute of Linguistics, Academia Sinica, Taipei, Taiwan on June 24-25, 2010. -

Tibet's Minority Languages-Diversity and Endangerment-Appendix 9 28 Sept Version

Tibet’s minority languages: Diversity and endangerment Short title: Tibet’s minority languages Authors: GERALD ROCHE (Asia Institute, University of Melbourne, [email protected])* HIROYUKI SUZUKI (IKOS, University of Oslo, [email protected]) Abstract Asia is the world’s most linguistically diverse continent, and its diversity largely conforms to established global patterns that correlate linguistic diversity with biodiversity, latitude, and topography. However, one Asian region stands out as an anomaly in these patterns—Tibet, which is often portrayed as linguistically homogenous. A growing body of research now suggests that Tibet is linguistically diverse. In this article, we examine this literature in an attempt to quantify Tibet’s linguistic diversity. We focus on the minority languages of Tibet—languages that are neither Chinese nor Tibetan. We provide five different estimates of how many minority languages are spoken in Tibet. We also interrogate these sources for clues about language endangerment among Tibet’s minority languages, and propose a sociolinguistic categorization of Tibet’s minority languages that enables broad patterns of language endangerment to be perceived. Appendices include lists of the languages identified in each of our five estimates, along with references to key sources on each language. Our survey found that as many as 60 minority languages may be spoken in Tibet, and that the majority of these languages are endangered to some degree. We hope out contribution inspires further research into the predicament of Tibet’s minority languages, and helps support community efforts to maintain and revitalize these languages. NB: This is the accepted version of this article, which was published in Modern Asian Studies in April 2018. -

Himalayan Linguistics a Geolinguistic Study of Directional Prefixes in The

Himalayan Linguistics A geolinguistic study of directional prefixes in the Qiangic language area Satoko Shirai Tokyo University of Foreign Studies ABSTRACT This study examines directional prefixes of the languages spoken in the Qiangic language area from a geolinguistic perspective. Among these languages, the northern languages tend to have more directional prefixes. This fact suggests the areal development of directional prefixes. I discuss the following eight directional prefixes: (i) “upward”, (ii) “downward”, (iii) “inward”, (iv) “outward”, (v) “upriver”, (vi) “downriver”, (vii) “eastward” and (viii) “westward”. These directional categories are based on nature such as landforms or space and are relatively common in Qiangic. First, I show the geographical distribution of the forms of prefixes for each directional category. Then, I make hypotheses on the historical development of directional prefixes using a geolinguistic method. I conclude that among these directional categories, (i)– (iv) are basic in the Qiangic language area. In other words, the other categories, (v)–(viii), developed later in each local area. The following are the oldest types of initial of each directional prefix: dental plosive for the “upriver” prefixes; dental nasal for the “downward” prefixes; voiceless velar plosive for the “inward” and “upriver” prefixes; voiced velar plosive for the “outward” and “downriver” prefixes; velar plosive for the “eastward” prefixes; and dental nasal for the “westward” prefixes. KEYWORDS Directional prefix, Qiangic, Geolinguistics, language area, GIS This is a contribution from Himalayan Linguistics, Vol. 19(1): 365–392. ISSN 1544-7502 © 2020. All rights reserved. This Portable Document Format (PDF) file may not be altered in any way. Tables of contents, abstracts, and submission guidelines are available at escholarship.org/uc/himalayanlinguistics Himalayan Linguistics, Vol. -

La Comunicazione Politica Cinese Rivolta All'estero

Memorie del Dipartimento di Giurisprudenza dell’Università di Torino TANINA ZAPPONE La comunicazione politica cinese rivolta all’estero: dibattito interno, istituzioni e pratica discorsiva MEMORIE DEL DIPARTIMENTO DI GIURISPRUDENZA DELL’UNIVERSITÀ DI TORINO 5/2017 TANINA ZAPPONE LA COMUNICAZIONE POLITICA CINESE RIVOLTA ALL’ESTERO: dibattito interno, istituzioni e pratica discorsiva Ledizioni Opera finanziata con il contributo del Dipartimento di Giurisprudenza dell’Università di Torino Il presente volume è stato preliminarmente sottoposto a un processo di referaggio anonimo, nel rispetto dell’anonimato sia dell’Autore sia dei revisori (double blind peer review). La valutazione è stata affidata a due esperti del tema trattato, designati dal Direttore del Dipartimento di Giurisprudenza dell’Università di Torino. Entrambi i revisori hanno formulato un giudizio positivo sull’opportunità di pubblicare il presente volume. © 2017 Ledizioni LediPublishing Via Alamanni, 11 – 20141 Milano – Italy www.ledizioni.it [email protected] Tanina Zappone, La comunicazione politica cinese rivolta all’estero: dibattito interno, istituzioni e pratica discorsiva. Prima edizione: novembre 2017 ISBN 9788867056798 Progetto grafico: ufficio grafico Ledizioni Informazioni sul catalogo e sulle ristampe dell’editore: www.ledizioni.it Le riproduzioni a uso differente da quello personale potranno avvenire, per un numero di pagine non superiore al 15% del presente volume, solo a seguito di specifica autorizzazione rilasciata da Ledizioni. Indice Ringraziamenti 8 Introduzione 11 L’emergere di una nuova visione della comunicazione internazionale: il dibattito cinese su diplomazia pubblica e soft power 13 Capitolo 1 L’introduzione delle nozioni di diplomazia pubblica e soft power nel discorso strategico cinese 17 1. Gli strumenti del governo, le perplessità del mondo occidentale e l’evoluzione del ruolo degli intellettuali 24 2. -

Lower Xumi, the Variety of the Lower and Middle Reaches of the Shuiluo River

ILLUSTRATIONS OF THE IPA Xumi (part 1): Lower Xumi, the variety of the lower and middle reaches of the Shuiluo river Katia Chirkova Centre de Recherches Linguistiques sur l’Asie Orientale, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Paris, France [email protected] Yiya Chen Leiden University Centre for Linguistics, Leiden Institute for Brain and Cognition, Leiden, the Netherlands [email protected] The Xumi !! language (/EPʃʉ-h˜ı ketɕɐ/‘thelanguageoftheShupeople’)isspokenby approximately 1,800 people who reside along the banks of the Shuiluo River (!!") in Shuiluo Township (!!!)ofMuliTibetanAutonomousCounty(!!!"!#!; smi li rang skyong rdzong in Written Tibetan, hereafter, WT).1 This county is located in the South-West of Sichuan Province (!!!)inthePeople’sRepublicofChina(see Figure 1). The language of the group was first described by Sun Hongkai (!"!)(Sun1983), who labeled it ‘Shixing "!’basedontheautonymofthegroup(/EPʃʉ-h˜ı/ ‘Xumi people’). However, this label is generally unknown in the county where the group resides and where its official name in the national Mandarin Chinese language is Xumi (!!) (Muli Gazetteers 2010: 560, 563–564, 568). Xumi is currently classified as a member of the putative Qiangic subgroup of the Sino- Tibetan language family (Bradley 1997: 36–37; Sun 2001). However, the recent migration history of the group from the areas historically populated by the Naxi and Mosuo ethnic groups, in combination with salient typological similarities between Xumi and the Naxi and Mosuo languages, rather suggest that Xumi is more closely related to those two languages (Guo & He 1994: 8–9; Chirkova 2009, 2012). Of old, Shuiluo Township is a multi-ethnic and multi-lingual area. -

View the 2020 ICSTLL Booklet In

International Conference on Sino-Tibetan Languages and Linguistics ICSTLL 53 will be hosted via ZOOM by the University of North Texas, October 2 - 4, 2020 with a pre-conference meeting of the Computational Resource for South Asian Languages on October 1st from 4:00 pm - 10:00 pm. (Central Standard Time) Advisory committee: • Mark Turin, Professor, Anthropology, University of British Columbia • Kristine Hildebrandt, Associate Professor, English, Southern Illinois University Edwardsville • Alexis Palmer, Assistant Professor, Linguistics, University of North Texas • Ken Van Bik, Assistant Professor, English, California State University Organizing committee: • Shobhana Chelliah (Lead Organizer), Associate Dean and Professor, College of Information, University of North Texas • Mary Burke, 3rd Year PhD Scholar, Information Science - Linguistics Concentration, University of North Texas • Marty Heaton, NSF-funded RA, 1st Year PhD Scholar, Information Science - Linguistics Concentration, University of North Texas • Adam Chavez, UNT College of Information, Web Content Manager • Sadaf Munshi, Professor and Chair, Linguistics, University of North Texas • Taraka Rama, Assistant Professor, Linguistics, University of North Texas • Oksana Zavalina, Associate Professor, Information Science, University of North Texas • Ava Jones, UNT College of Information, Communications Specialist Welcome As the Dean of the College of Information at the University of North Texas (UNT), it is an honor and a pleasure to welcome you at the International Conference on Sino-Tibetan Languages and Linguistics (ICSTLL53), taking place online during October 2-4, 2020. We at UNT are proud to have a world-class Linguistics department, with distinguished researchers who are involved in cutting-edge research funded by NSF, IMLS and others. With that backdrop, I am confident that the hosting of ICSTLL53 will not only benefit from the exchange of those pioneering efforts but also advance the field further, aligned with the expectations of UNT as a Tier 1 Carnegie Research university. -

Numeral Classifiers in Ersu*

Article Language and Linguistics Numeral Classifiers in Ersu* 15(6) 883–915 © The Author(s) 2014 Reprints and permissions: sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/1606822X14544624 Sihong Zhang lin.sagepub.com Anhui University of Chinese Medicine James Cook University This paper analyzes the numeral classifier system in Ersu, a previously under-documented Tibeto-Burman language spoken in Sichuan Province, China. Ersu numeral classifiers obligatorily follow a numeral in the context of counting. The language has a rich set of numeral classifiers, including sortal classifiers, mensural classifiers, time classifiers and repeaters. Their functional range involves individualization, classification, referentialization and emphasis. The paper concludes that Ersu not only shares common features with other Tibeto-Burman languages in this area, but also has some unique typological characteristics. Key words: Ersu, numeral classifiers, Tibeto-Burman language * The paper is part of an earlier version, ‘Classifiers in Ersu’, which was presented at the 13th International Symposium on Chinese Languages and Linguistics held in National Taiwan Normal University on June 1, 2012. I thank all the conference participants for their useful comments. I am grateful to Alexandra Aikhenvald, R. M. W. Dixon, and Mark Post for their supervision during the whole process of my PhD research. Special thanks go to Alexandra Aikhenvald and Mark Post for their careful and dedicated reading, comments and corrections while I was writing this paper. I thank Brigitta Flick and Nerida Jarkey for their professional proofreading. I must also thank Walter Bisang, Katia Chirkova, and the two anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and suggestions that have greatly improved the quality of this paper. -

2017 Annual Report .Pdf

CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2017 ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION OCTOBER 5, 2017 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov VerDate Nov 24 2008 16:24 Oct 04, 2017 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6011 Sfmt 5011 U:\DOCS\26811 DIEDRE 2017 ANNUAL REPORT VerDate Nov 24 2008 16:24 Oct 04, 2017 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 6019 Sfmt 6019 U:\DOCS\26811 DIEDRE CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2017 ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION OCTOBER 5, 2017 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 26–811 PDF WASHINGTON : 2017 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Nov 24 2008 16:24 Oct 04, 2017 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 U:\DOCS\26811 DIEDRE CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA LEGISLATIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS Senate House MARCO RUBIO, Florida, Chairman CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey, JAMES LANKFORD, Oklahoma Cochairman TOM COTTON, Arkansas ROBERT PITTENGER, North Carolina STEVE DAINES, Montana TRENT FRANKS, Arizona TODD YOUNG, Indiana RANDY HULTGREN, Illinois DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California MARCY KAPTUR, Ohio JEFF MERKLEY, Oregon TIMOTHY J. WALZ, Minnesota GARY PETERS, Michigan TED LIEU, California ANGUS KING, Maine EXECUTIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS Department of State, To Be Appointed Department of Labor, To Be Appointed Department of Commerce, To Be Appointed At-Large, To Be Appointed At-Large, To Be Appointed ELYSE B. -

Congressional-Executive Commission on China

CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2005 ONE HUNDRED NINTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION 3, 2009 April v. Holder,OCTOBER 11, 2005on in Liv archived Cited Printed 05-70053for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China No. ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 23–753 PDF WASHINGTON : 2005 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 11-MAY-2000 19:18 Oct 07, 2005 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 U:\DOCS\23753.TXT CHINA1 PsN: CHINA1 CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA LEGISLATIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS Senate House CHUCK HAGEL, Nebraska, Chairman JAMES A. LEACH, Iowa, Co-Chairman SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas DAVID DREIER, California GORDON SMITH, Oregon FRANK WOLF, Virginia JIM DEMINT, South Carolina JOSEPH R. PITTS, Pennsylvania MEL MARTINEZ, Florida ROBERT B. ADERHOLT, Alabama MAX BAUCUS, Montana SANDER LEVIN, Michigan CARL LEVIN, Michigan MARCY KAPTUR, Ohio DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California SHERROD BROWN, Ohio BYRON DORGAN, North Dakota MICHAEL M. HONDA, California EXECUTIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS STEVEN J. LAW, Department of Labor PAULA DOBRIANSKY, Department of State DAVID DORMAN, Staff Director (Chairman) JOHN FOARDE, Staff Director (Co-Chairman) (II) 3, 2009 April v. Holder, on in Liv archived Cited 05-70053 No. VerDate 11-MAY-2000 19:18 Oct 07, 2005 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 0486 Sfmt 0486 U:\DOCS\23753.TXT CHINA1 PsN: CHINA1 C O N T E N T S Page I. -

Diachronic Developments of Voiceless Nasals in Ersu, Lizu, And

Diachronic developments of voiceless nasals: the case of Ersu, Lizu, and related languages Katia Chirkova, CNRS-CRLAO, Paris Zev Handel, University of Washington, Seattle Note: This is an updated (October 5, 2013) written version of the presentation Diachronic Developments of Voiceless Nasals in Ersu, Lizu, and Related Languages made at the 46th International Conference on Sino-Tibetan Languages and Linguistics Dartmouth, August 8-10, 2013 Abstract Ersu, Lizu and Duoxu (collectively ELD) are three closely related, little-studied Tibeto-Burman [TB] languages of Sichuan Province in China. Their position within the broader TB family is a matter of dispute. Recent analyses variously link them to other lesser-known TB languages of Sichuan (known under the term Qiangic, Sūn 2001a) or consider them more closely related to the Naish languages (Bradley 2008, 2012; Jacques & Michaud 2011). This study presents one significant new finding for the reconstruction of Proto-ELD (going beyond the conclusions of Yu 2012): the existence of voiceless nasal onsets. This finding not only illuminates the broader problem of classification of the languages of the area, it also suggests the existence of a universal pathway of sequenced changes related to the development and loss of voiceless nasals in languages of the world. The study makes use of a significant amount of new data arising from recent fieldwork. The conclusions are based on a combination of (i) the techniques of the comparative method within the ELD cluster, (ii) external comparison with cognates elsewhere in Tibeto-Burman, and (iii) analysis of universal phonetic mechanisms and constraints. Voiceless nasals are posited based on cognate sets like the following for ‘ripe’, showing a correspondence between a voiceless fricative in Ersu, a voiceless nasal approximant in Lizu, and a nasal stop in Duoxu: Ersu /(dɛ³¹-)xe⁵¹/, Lizu /(de³³-)h̃e⁵¹/, Duoxu /me³⁴/ The reconstruction is supported by cognate forms elsewhere in TB (for example, Written Burmese /m̥ ɛ1/ ‘ripe’ and Written Tibetan smyin ‘ripe’). -

Paris, Sept. 2013)

3rd Workshop on Sino- Tibetan Languages of Sichuan (Paris, Sept. 2013) 2-4 Sep 2013 France Table of Contents Certain Phonological Peculiarities of Taku Tibetan, J. Sun......................................................................1 Time Ordinals in Ngwi Languages of Sichuan, D. Bradley..................................................................... 2 A Study of Malimasa Phonology: Synchronic Analysis and Diachronic Hypothesis, L. Zihe................ 3 Complexities in a simple level-tone system: Phonological and phonetic perspectives on Lijiazui Na, D. Xu............................................................................................................................................................. 5 Lataddi Narua Tones: The tonal system of a Si?chua?n variety of Yo?ngni?ng Na, R. Dobbs................7 Phrasing, prominence, and morphotonology: How utterances are divided into tone groups in Yongning Na, A. Michaud....................................................................................................................................... 10 Synchronic analysis and diachronic development of obstruent vowels in Ersu and Lizu, K. Chirkova [et al.] ...........................................................................................................................................................12 Tense and Aspect Morphology in Lizu: A First Look, Y. Lin [et al.] .....................................................14 Verb predicate Structure in the Mu-nya language, T. Ikeda....................................................................15