United Nations: Time for a New “Inquiry”? MICHAEL J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proceedings 207

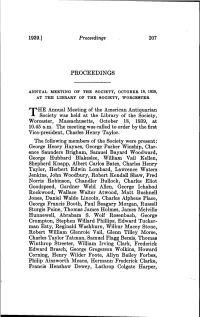

1939.] Proceedings 207 PROCEEDINGS ANNUAL MEETING OP THE SOCIETY, OCTOBER 18, 1939, AT THE LIBEARY OF THE SOCIETY, WORCESTER Annual Meeting of the Anierican Antiquarian -1 Society was held at the Library of the Society, Worcester, Massachusetts, October 18, 1939, at 10.45 a.m. The meeting was called to order by the first Vice-president, Charles Henry Taylor. The following members of the Society were present : George Henry Haynes, George Parker Winship, Clar- ence Saunders Brigham, Samuel Bayard Woodward, George Hubbard Blakeslee, William Vail Kellen, Shepherd Knapp, Albert Carlos Bates, Charles Henry Taylor, Herbert Edwin Lombard, Lawrence Waters Jenkins, John Woodbury, Robert Kendall Shaw, Fred Norris Robinson, Chandler BuUockj Charles Eliot Goodspeed, Gardner Weld Allen, George Ichabod Rockwood, Wallace Walter Atwood, Matt Bushneil Jones, Daniel Waldo Lincoln, Charles Alpheus Place, George Francis Booth, Paul Beagary Morgan, Russell Sturgis Paine, Thomas James Holmes, James Melville Hunnewell, Abraham S. Wolf Rosenbach, George Crompton, Stephen Willard Phillips, Edward Tucker- man Esty, Reginald Washburn, Wilbur Macey Stone, Robert William Glenroie Vail, Glenn Tilley Morse, Charles Taylor Tatman, Samuel Flagg Bemis, Thomas Winthrop Streeter, William Irving Clark, Frederick Edward Brasch, George Gregerson Wolkins, Howard Corning, Henry Wilder Foote, Allyn Bailey Forbes, Philip Ainsworth Means, Hermann Frederick Clarke, Francis Henshaw Dewey, Lathrop Colgate Harper, 208 American Antiquarian Society [Oct., Augustus Peabody Loring, Jr., James Duncan Phillips, Clifford Kenyon Shipton, Alexander Hamilton Bullock, Theron Johnson Damon, Albert White Rice, Fred- erick Lewis Weis, Donald McKay Frost, Harry- Andrew Wright. It was voted to dispense with the reading of the records of the last meeting. The report of the Council of the Society was presented by the Director, Mr. -

University Microfilms Copyright 1984 by Mitchell, Reavis Lee, Jr. All

8404787 Mitchell, Reavis Lee, Jr. BLACKS IN AMERICAN HISTORY TEXTBOOKS: A STUDY OF SELECTED THEMES IN POST-1900 COLLEGE LEVEL SURVEYS Middle Tennessee State University D.A. 1983 University Microfilms Internet ion elæ o N. Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106 Copyright 1984 by Mitchell, Reavis Lee, Jr. All Rights Reserved Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. PLEASE NOTE: In all cases this material has been filmed in the best possible way from the available copy. Problems encountered with this document have been identified here with a check mark V 1. Glossy photographs or pages. 2. Colored illustrations, paper or print_____ 3. Photographs with dark background_____ 4. Illustrations are poor copy______ 5. Pages with black marks, not original copy_ 6. Print shows through as there is text on both sides of page. 7. Indistinct, broken or small print on several pages______ 8. Print exceeds margin requirements______ 9. Tightly bound copy with print lost in spine______ 10. Computer printout pages with indistinct print. 11. Page(s)____________ lacking when material received, and not available from school or author. 12. Page(s) 18 seem to be missing in numbering only as text follows. 13. Two pages numbered _______iq . Text follows. 14. Curling and wrinkled pages______ 15. Other ________ University Microfilms International Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. BLACKS IN AMERICAN HISTORY TEXTBOOKS: A STUDY OF SELECTED THEMES IN POST-190 0 COLLEGE LEVEL SURVEYS Reavis Lee Mitchell, Jr. A dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of Middle Tennessee State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Arts December, 1983 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

20 American Antiquarian Society Lications of American Writers. One

20 American Antiquarian Society lications of American writers. One of his earliest catalogues was devoted to these early efforts and this has been followed at intervals by others in the same vein. This was, however, only one facet of his interests and the scholarly catalogues he published covering fiction, poetry, drama, and bibliographical works provide a valuable commentary on the history and the changing fashions of American book buying over four de- cades. The shop established on the premises at S West Forty- sixth Street in New York by Kohn and Papantonio shortly after the end of the war has become a mecca for bibliophiles from all over the United States and from foreign countries. It is not overstating the case to say that Kohn became the leading authority on first and important editions of American literature. He was an interested and active member of the American Antiquarian Society. The Society's incomparable holdings in American literature have been enriched by his counsel and his gifts. He will be sorely missed as a member, a friend, and a benefactor. C. Waller Barrett SAMUEL ELIOT MORISON Samuel Eliot Morison was born in Boston on July 9, 1887, and died there nearly eighty-nine years later on May 15, 1976. He lived most of his life at 44 Brimmer Street in Bos- ton. He graduated from Harvard in 1908, sharing a family tradition with, among others, several Samuel Eliots, Presi- dent Charles W. Eliot, Charles Eliot Norton, and Eking E. Morison. During his junior year he decided on teaching and writing history as an objective after graduation and in his twenty-fifth Harvard class report, he wrote: 'History is a hu- mane discipline that sharpens the intellect and broadens the mind, offers contacts with people, nations, and civilizations. -

Suicide Facts Oladeinde Is a Staff Writerall for Hands Suicide Is on the Rise Nationwide

A L p AN Stephen Murphy (left),of Boston, AMSAN Kevin Sitterson (center), of Roper, N.C., and AN Rick Martell,of Bronx, N.Y., await the launch of an F-14 Tomcat on the flight deckof USS Theodore Roosevelt (CVN 71). e 4 24 e 6 e e Hidden secrets Operation Deliberate Force e e The holidays are a time for giving. USS Theodore Roosevelt (CVN 71) e e proves what it is made of during one of e e Make time for your shipmates- it e e could be the gift of life. the biggest military operations in Europe e e since World War 11. e e e e 6 e e 28 e e Grab those Gifts e e Merchants say thanks to those in This duty’s notso tough e e uniform. Your ID card is worth more Nine-section duty is off to a great start e e e e than you may think. and gets rave reviews aboardUSS e e Anchorage (LSD 36). e e PAGE 17 e e 10 e e The right combination 30 e e e e Norfolk hospital corpsman does studio Sailors care,do their fair share e e time at night. Seabees from CBU420 build a Habitat e e e e for Humanity house in Jacksonville, Fla. e e 12 e e e e Rhyme tyme 36 e e Nautical rhymes bring the past to Smart ideas start here e e e e everyday life. See how many you Sailors learn the ropes and get off to a e e remember. -

Jefferson's Failed Anti-Slavery Priviso of 1784 and the Nascence of Free Soil Constitutionalism

MERKEL_FINAL 4/3/2008 9:41:47 AM Jefferson’s Failed Anti-Slavery Proviso of 1784 and the Nascence of Free Soil Constitutionalism William G. Merkel∗ ABSTRACT Despite his severe racism and inextricable personal commit- ments to slavery, Thomas Jefferson made profoundly significant con- tributions to the rise of anti-slavery constitutionalism. This Article examines the narrowly defeated anti-slavery plank in the Territorial Governance Act drafted by Jefferson and ratified by Congress in 1784. The provision would have prohibited slavery in all new states carved out of the western territories ceded to the national government estab- lished under the Articles of Confederation. The Act set out the prin- ciple that new states would be admitted to the Union on equal terms with existing members, and provided the blueprint for the Republi- can Guarantee Clause and prohibitions against titles of nobility in the United States Constitution of 1788. The defeated anti-slavery plank inspired the anti-slavery proviso successfully passed into law with the Northwest Ordinance of 1787. Unlike that Ordinance’s famous anti- slavery clause, Jefferson’s defeated provision would have applied south as well as north of the Ohio River. ∗ Associate Professor of Law, Washburn University; D. Phil., University of Ox- ford, (History); J.D., Columbia University. Thanks to Sarah Barringer Gordon, Thomas Grey, and Larry Kramer for insightful comment and critique at the Yale/Stanford Junior Faculty Forum in June 2006. The paper benefited greatly from probing questions by members of the University of Kansas and Washburn Law facul- ties at faculty lunches. Colin Bonwick, Richard Carwardine, Michael Dorf, Daniel W. -

Above the World: William Jennings Bryan's View of the American

Nebraska History posts materials online for your personal use. Please remember that the contents of Nebraska History are copyrighted by the Nebraska State Historical Society (except for materials credited to other institutions). The NSHS retains its copyrights even to materials it posts on the web. For permission to re-use materials or for photo ordering information, please see: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/magazine/permission.htm Nebraska State Historical Society members receive four issues of Nebraska History and four issues of Nebraska History News annually. For membership information, see: http://nebraskahistory.org/admin/members/index.htm Article Title: Above the World: William Jennings Bryan’s View of the American Nation in International Affairs Full Citation: Arthur Bud Ogle, “Above the World: William Jennings Bryan’s View of the American Nation in International Affairs,” Nebraska History 61 (1980): 153-171. URL of article: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/publish/publicat/history/full-text/1980-2-Bryan_Intl_Affairs.pdf Date: 2/17/2010 Article Summary: One of the major elements in Bryan’s intellectual and political life has been largely ignored by both critics and admirers of William Jennings Bryan: his vital patriotism and nationalism. By clarifying Bryan’s Americanism, the author illuminates an essential element in his political philosophy and the consistent reason behind his foreign policy. Domestically Bryan thought the United States could be a unified monolithic community. Internationally he thought America still dominated her hemisphere and could, by sheer energy and purity of commitment, re-order the world. Bryan failed to understand that his vision of the American national was unrealizable. The America he believed in was totally vulnerable to domestic intolerance and international arrogance. -

Bernard Bailyn, W

Acad. Quest. (2021) 34.1 10.51845/34s.1.24 DOI 10.51845/34s.1.24 Reviews He won the Pulitzer Prize in history twice: in 1968 for The Ideological Illuminating History: A Retrospective Origins of the American Revolution of Seven Decades, Bernard Bailyn, W. and in 1987 for Voyagers to the West, W. Norton & Company, 2020, 270 pp., one of several volumes he devoted $28.95 hardbound. to the rising field of Atlantic history. Though Bailyn illuminated better than most scholars the contours of Bernard Bailyn: An seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Historian to Learn From American history, his final book hints at his growing concern about the Robert L. Paquette rampant opportunism and pernicious theoretical faddishness that was corrupting the discipline he loved and to which he had committed his Bernard Bailyn died at the age professional life. of ninety-seven, four months after Illuminating History consists of publication of this captivating curio five chapters. Each serves as kind of of a book, part autobiography, part a scenic overlook during episodes meditation, part history, and part of a lengthy intellectual journey. historiography. Once discharged At each stop, Bailyn brings to the from the army at the end of World fore little known documents or an War II and settled into the discipline obscure person’s life to open up of history at Harvard University, views into a larger, more complicated Bailyn undertook an ambitious quest universe, which he had tackled to understand nothing less than with greater depth and detail in the structures, forces, and ideas previously published books and that ushered in the modern world. -

Curtis Putnam Nettels

Curtis Putnam Nettels August 25, 1898 — October 19, 1981 Curtis Putnam Nettels, trained at the University of Kansas and the University of Wisconsin, had an active teaching career at the University of Wisconsin and Cornell from 1924 to 1966. From the outset he centered his research and writing in the colonial and early national period and quickly became one of the best and most effective teachers, writers, and critics on seventeenth- and eighteenth-century America. His move to Cornell pushed its Department of History into the front rank of colonial history. Nettels was born in Topeka, Kansas, from old New England stock, as all three of his names suggest. His father was a court stenographer, local politician, and lover of music, as his son became. With the University of Kansas only twenty miles away, it was natural for him to go there for his undergraduate education and equally natural that he should do his graduate work at Wisconsin, which had a very strong American history section. Under the influence of Frank Hodder at Kansas, who had begun his teaching at Cornell University in 1885, and Frederic L. Paxson, the ‘frontier” historian who succeeded Frederick Jackson Turner when he left Wisconsin for Harvard in 1910, and in an atmosphere permeated by the progressivism of Richard Ely, John R. Commons, and Selig Perlman in eonomics; John M. Gaus in government; E. A. Ross in sociology; and, most of all, the LaFollette family, Nettels emerged as a progressive historian, concerned about the problems modern industrialism had created, the ravages that uncontrolled capitalism had done to soil, forests, and water of the West. -

Lawrence Henry Gipson's Empire: the Critics

LAWRENCE HENRY GIPSON'S EMPIRE: THE CRITICS ED. BY WILLIAM G. SHADE X N 1936 Charles McLean Andrews, then the foremost of American Colonial historians, wrote after reading the maanu- script of the first three volumes of Lawrence Henry Gipson's, The British Empire before the American Revolution, "I want to say how highly I value the work in question. It is unique in its scope and thoroughness and in more ways than one is a remarkable production. I had the privilege of reading it in manuscript and recognized at the time the breadth, originality and ripeness of the treatment. There is nothing written on the subject that approaches it in comprehensiveness and artistry of execution. To students of the Anglo-colonial relationship it will be indispensable."' This monumental series, now numbering fourteen volumes with yet another planned, was conceived in the 1920's and the first volumes appeared in 1936 when their author was at an age when most men contemplate retirement rather than moving forward on a project of such magnitude. After over thirty years, the text has been completed and it is clear that the series represents not only the mature consideration of a major topic by a master historian, but as Esmond Wright has put it, "the ne plus ultra of the im- perialist view"2 of the origins of the American Revolution. The "imperialist view" of the American Revolution can be traced back to the Tory historians of the eighteenth century, but is gen- erally associated with that generation of historians in the early twentieth century including Herbert L. -

29 from the Library of Professor Richard B. Dinsmore, Phd FY2006

From the Library of Professor Richard B. Dinsmore, PhD FY2006 1848 : The Revolutionary Tide in Europe / Peter N. Stearns 500 Popular Annuals and Perennials for American Gardeners / Edited by Loretta Barnard About Philosophy / Robert Paul Wolff Absolutism and Enlightenment, 1660-1789 / R. W. Harris Action Française; Royalism and Reaction in Twentieth-Century France Action Française; Die-Hard Reactionaries in Twentieth-Century France Adding on / Editors of Time-Life Books Advanced Woodworking / Editors of Time-Life Books After Everything : Western Intellectual History Since 1945 / Roland N. Stromberg Age of Louis XIV Age of Nationalism and Reform, 1850-1890 Age of Revolution and Reaction, 1789-1850 Age of the Economist / Daniel R. Fusfeld Age of Controversy: Discussion Problems in 20th Century European History / Gordon Wright Alexander the Great : Legacy of a Conqueror / Winthrop Lindsay Adams All Quiet on the Western Front / Erich Maria Remarque All About Market Timing : The Easy Way to Get Started / Leslie N. Masonson An Intellectual History of Modern Europe / Roland N. Stromberg Ancien Régime; French Society 1600-1750. Translated by Steve Cox Ancien Régime / Hubert Méthivier Ancient Near Eastern Tradition Ancient World Ancient Near East Anticlericalism; Conflict Between Church & State in France, Italy, and Spain / J. S. Schapiro Antony and Cleopatra / Louis B. Wright and Virginia Lamar Army of the Republic, 1871-1914 / David B. Ralston Art of Cross-Examination / Francis L. Wellman Artisans and Sans-culottes; Popular Movements in France and Britain... / Gwyn A. Williams Aspects of Western Civilization : Problems and Sources in History / Edited by Perry M. Rogers Aspects of Western Civilization : Problems and Sources in History / Edited by Perry M. -

The Large Book Versus the Small a Presidential Historian’S Consideration of Three Recent Biographies

The Large Book versus the Small A Presidential Historian’s Consideration of Three Recent Biographies ROBERT H. FERRELL urs seems to be the time of the large book, those huge bestsellers 0that cover the tables in bookstores across the country. The bio- graphical volumes among these books might be described as “lives and times.” They are written in such an exquisite amount of detail that they present a challenge to readers, both scholarly and non. Older scholars like myself find the books of younger historians piling up around us, and we wonder where we might find time to read such a flood. Confronting an eight-hundred-page biography, and calculating twenty to twenty-five pages per hour for reading, each of these onrushing books would require thirty or forty hours of time. Unless, that is, we skimmed; whereupon we could respond positively to the queries of younger colleagues as to whether we had read the latest scholarship. We had-that is, we had scampered through several hundred pages in an hour, or maybe two or three. The trend toward the dominance of the large book in historical biog- raphy is, in my judgment, radically wrong. But it does have a history, and understanding something of the context of today’s over-long historical Robert H. Ferrell is professor emeritus of history at Indiana University Bloomington. INDIANA MAGAZINE OF HISTORY, 100 (December 2004). 0 2004, Trustees of Indiana University. RECENT PRESIDENTIAL BIOGRAPHIES 379 blockbusters may help to make more sense of the books under consider- ation in this review essay. The first generation of scholars to produce these large books did so under the influence of the late Samuel Eliot Morison, Harvard professor and dean of post-World-War-I1 American historians. -

Harvard Confederates Who Fell in the Civil

Advocates for Harvard ROTC H CRIMSON CLUB MEMBER VETERANS As a result of their military service, Crimson warriors became part of a “Band of Brothers”. The following is an illustrative but not exhaustive listing of military oriented biographies of veterans whose initial exposure to non-family “brotherhood” were as members of various social and final clubs as undergraduates at Harvard. CIVIL WAR - HARVARD COLLEGE BY CLASS 18 34 Major General Henry C. Wayne CSA Born in Georgia – Georgia Militia Infantry Henry was the son of a lawyer and US congressman from Georgia who was later appointed as justice to the US Supreme Court by President Andrew Jackson. He prepared at the Williston School in Northampton (MA) for Harvard where he was member of the Porcellian Club. In his junior year at Harvard, he received and accepted an appointment to West Point where he graduated 14th out of 45 in 1838. Among his class mates at West Point were future flag officers: Major General Irvin McDowell USA who was defeated at the 1st battle of Bull Run, General P.G.T. Beauregard CSA who was the victor at the1st battle of Bull Run as well as numerous other major Civil War engagements and Lt. General William J. Hardee CSA who served in both Mexican War and throughput the Civil War. After West Point, Henry was commissioned as a 2nd LT and served for 3 years with the 4th US Artillery on the frontiers border of NY and ME during a border dispute with Canada. He then taught artillery and cavalry tactics at West Point for 5 years before joining General Winfield Scott’s column from Vera Cruz to Mexico City during in the Mexican War.