Management Summary of an Archaeological Survey of a Portion of the Willbrook Development, Georgetown County, South Carolina

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

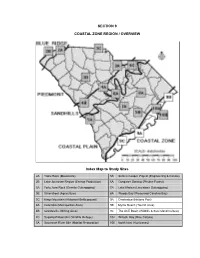

Coastal Zone Region / Overview

SECTION 9 COASTAL ZONE REGION / OVERVIEW Index Map to Study Sites 2A Table Rock (Mountains) 5B Santee Cooper Project (Engineering & Canals) 2B Lake Jocassee Region (Energy Production) 6A Congaree Swamp (Pristine Forest) 3A Forty Acre Rock (Granite Outcropping) 7A Lake Marion (Limestone Outcropping) 3B Silverstreet (Agriculture) 8A Woods Bay (Preserved Carolina Bay) 3C Kings Mountain (Historical Battleground) 9A Charleston (Historic Port) 4A Columbia (Metropolitan Area) 9B Myrtle Beach (Tourist Area) 4B Graniteville (Mining Area) 9C The ACE Basin (Wildlife & Sea Island Culture) 4C Sugarloaf Mountain (Wildlife Refuge) 10A Winyah Bay (Rice Culture) 5A Savannah River Site (Habitat Restoration) 10B North Inlet (Hurricanes) TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR SECTION 9 COASTAL ZONE REGION / OVERVIEW - Index Map to Coastal Zone Overview Study Sites - Table of Contents for Section 9 - Power Thinking Activity - "Turtle Trot" - Performance Objectives - Background Information - Description of Landforms, Drainage Patterns, and Geologic Processes p. 9-2 . - Characteristic Landforms of the Coastal Zone p. 9-2 . - Geographic Features of Special Interest p. 9-3 . - Carolina Grand Strand p. 9-3 . - Santee Delta p. 9-4 . - Sea Islands - Influence of Topography on Historical Events and Cultural Trends p. 9-5 . - Coastal Zone Attracts Settlers p. 9-5 . - Native American Coastal Cultures p. 9-5 . - Early Spanish Settlements p. 9-5 . - Establishment of Santa Elena p. 9-6 . - Charles Towne: First British Settlement p. 9-6 . - Eliza Lucas Pinckney Introduces Indigo p. 9-7 . - figure 9-1 - "Map of Colonial Agriculture" p. 9-8 . - Pirates: A Coastal Zone Legacy p. 9-9 . - Charleston Under Siege During the Civil War p. 9-9 . - The Battle of Port Royal Sound p. -

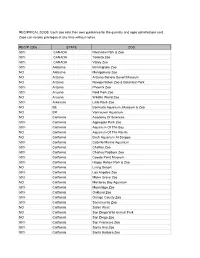

2006 Reciprocal List

RECIPRICAL ZOOS. Each zoo sets their own guidelines for the quantity and ages admitted per card. Zoos can revoke privileges at any time without notice. RECIP 2006 STATE ZOO 50% CANADA Riverview Park & Zoo 50% CANADA Toronto Zoo 50% CANADA Valley Zoo 50% Alabama Birmingham Zoo NO Alabama Montgomery Zoo NO Arizona Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum NO Arizona Navajo Nation Zoo & Botanical Park 50% Arizona Phoenix Zoo 50% Arizona Reid Park Zoo NO Arizona Wildlife World Zoo 50% Arkansas Little Rock Zoo NO BE Bermuda Aquarium, Museum & Zoo NO BR Vancouver Aquarium NO California Academy Of Sciences 50% California Applegate Park Zoo 50% California Aquarium Of The Bay NO California Aquarium Of The Pacific NO California Birch Aquarium At Scripps 50% California Cabrillo Marine Aquarium 50% California Chaffee Zoo 50% California Charles Paddock Zoo 50% California Coyote Point Museum 50% California Happy Hollow Park & Zoo NO California Living Desert 50% California Los Angeles Zoo 50% California Micke Grove Zoo NO California Monterey Bay Aquarium 50% California Moonridge Zoo 50% California Oakland Zoo 50% California Orange County Zoo 50% California Sacramento Zoo NO California Safari West NO California San Diego Wild Animal Park NO California San Diego Zoo 50% California San Francisco Zoo 50% California Santa Ana Zoo 50% California Santa Barbara Zoo NO California Seaworld San Diego 50% California Sequoia Park Zoo NO California Six Flags Marine World NO California Steinhart Aquarium NO CANADA Calgary Zoo 50% Colorado Butterfly Pavilion NO Colorado Cheyenne -

National Center for Preservation Technology and Training

National Center for National Park Service NCPTT Preservation Technology and Training U.S. Department of the Interior Annual Report for the period October 1,1994 — September 30,1998 To the President and Congress NCPTT Purposes The Preservation Technology and Training Board is pleased to be part of a new and critically NCPTT has five legislated purposes — needed, initiative of the National Park Service — the National Center for Preservation Technology and Training. The opportunity to bring our varied professional experience to bear "(1) develop and distribute preservation and conservation skills and technologies for the on NCPTT's development — and to see so much accomplished in the first four years — has identification, evaluation, conservation, and interpretation of prehistoric and historic been both exciting and rewarding. This report describes important new work that has had resources; remarkable nationwide impact in a very short time — an accomplishment with which this advisory board is proud to be associated. "(2) develop and facilitate training for Federal, State and local resource preservation professionals, cultural resource managers, maintenance personnel, and others working in the preservation Dr. Elizabeth A. Lyon field; On behalf of the Preservation Technology and Training Board November 1998 "(3) take steps to apply preservation technology benefits from ongoing research by other agencies and institutions; Creating NCPTT "(4) facilitate the transfer of preservation technology among Federal agencies, State and local In the mid-1980s, the U.S. Congress, responding to decades of concern from the preservation governments, universities, international organizations, and the private sector; and community, commissioned its Office of Technology Assessment to examine the relationship between technology and the development of the national preservation industry. -

Waccamaw River Blue Trail

ABOUT THE WACCAMAW RIVER BLUE TRAIL The Waccamaw River Blue Trail extends the entire length of the river in North and South Carolina. Beginning near Lake Waccamaw, a permanently inundated Carolina Bay, the river meanders through the Waccamaw River Heritage Preserve, City of Conway, and Waccamaw National Wildlife Refuge before merging with the Intracoastal Waterway where it passes historic rice fields, Brookgreen Gardens, Sandy Island, and ends at Winyah Bay near Georgetown. Over 140 miles of river invite the paddler to explore its unique natural, historical and cultural features. Its black waters, cypress swamps and tidal marshes are home to many rare species of plants and animals. The river is also steeped in history with Native American settlements, Civil War sites, rice and indigo plantations, which highlight the Gullah-Geechee culture, as well as many historic homes, churches, shops, and remnants of industries that were once served by steamships. To protect this important natural resource, American Rivers, Waccamaw RIVERKEEPER®, and many local partners worked together to establish the Waccamaw River Blue Trail, providing greater access to the river and its recreation opportunities. A Blue Trail is a river adopted by a local community that is dedicated to improving family-friendly recreation such as fishing, boating, and wildlife watching and to conserving riverside land and water resources. Just as hiking trails are designed to help people explore the land, Blue Trails help people discover their rivers. They help communities improve recreation and tourism, benefit local businesses and the economy, and protect river health for the benefit of people, wildlife, and future generations. -

New Discoveries D

NEWDISCOVERIES... By Gwen Thurmond and Joquita Burka At every turn in the road, every day of your visit to South 2,000 butterflies, moths and birds. The facility allows visitors Carolina, you’ll discover something new. It may be the to observe these living creatures interacting in a carefully newest restaurant, an “undiscovered” artist, a hidden garden reproduced natural habitat. or an artisan practicing in the “old ways.” This year’s discoveries The Butterfly Pavilion’s Nature Zone Discovery Center cover everything from butterflies to blacksmiths, sea turtles features live insects, reptiles, amphibians and arachnids. Visitors to showcase homes. No matter how many times you come to are transported to the mountains of Mexico surrounded by a South Carolina, you never find just exactly the same adventure. re-creation of towering fir trees and thousands of over wintering Monarch butterflies in a breathtaking sunrise BUTTERFLY PAVILION setting. The 22,500-square-foot Butterfly Pavilion, slated to open The Butterfly Conservatory, a glass structure towering 40 in the spring of 2001 at Broadway at the Beach in Myrtle feet, encompasses 9,000 square feet of lush landscape. Beach, is the first facility in the United States to incorporate a Thousands of native North American butterflies and moths fully enclosed glass conservatory featuring native North make their homes among carefully reproduced natural American butterflies. A fun-filled attraction and learning center habitats transformed into tropical, woodlands, cottage and for nature enthusiasts of all ages, Butterfly Pavilion features formal gardens. hands-on science exhibits and aviaries housing more than www.DiscoverSouthCarolina.com SOUTH CAROLINA AQUARIUM From the banks of the Bahamas to the seas of Argentina, Visitors to the Charleston area are discovering the South visitors will go underwater to meet Dolphins and get a new Carolina Aquarium, a $70-million science museum located perspective on their lives and remarkable intelligence. -

Brookgreen Gardens, S.C. : Acoustiguide Tour of the Sculpture Garden

Brookgreen Gardens, S.C. : acoustiguide tour of the sculpture garden Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 1 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 1 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 1 Container Listing ...................................................................................................... Brookgreen Gardens, S.C. : acoustiguide tour of the sculpture garden AAA.broogard Collection Overview Repository: Archives of American Art Title: Brookgreen Gardens, S.C. : acoustiguide tour of the sculpture garden Identifier: AAA.broogard Date: 1971 Creator: Brookgreen Gardens Extent: 1 Sound cassette (Sound recording) Language: English . Administrative Information Acquisition Information Provenance unknown. Restrictions Untranscribed; use requires an appointment. Biographical / Historical Sculpture garden, Murrells Inlet, S.C. Est. 1931 by Archer Huntington -

Lowcountry Spring 2016 Newsletter

OUTH AROLINA S C N ATIVE PLANT SOCIETY SPRING 2016 LOWCOUNTRY CHAPTER NEWSLETTER, VOL. 18, Issue 2, Mt. Pleasant, SC 29464 Happy New Year! I can hardly wait to break into my spring garden, and fortunately we have multiple opportunities ahead this spring to help you be the best gardener possible. Join us in February for a hands-on workshop on invasive and native plant identification and management at Charles Towne Landing. In our April lecture, local landscape architect J.R. Kramer will tell us about incorporating native plants in innovative ways into our developed landscapes. Plan to bring some inspiration from Brookgreen Gardens home with you after our special guided tour led by one of the staff horticulturalists. And don’t forget to mark your calendars now for our annual spring plant sale on March 19! I am excited to announce that we awarded our first community project grant ($500) in the fall to James B. Edwards Elementary School. The money will help students purchase supplies to erect a hoop house on the school grounds. They plan to use this facility to grow various native plants as well as spartina grass for the Seeds to Shoreline Program. Native plants will be grown within the house to be transplanted into the school garden to promote indigenous fauna and teach sustainable ecosystems. The spartina grass will be transplanted into receding estuary coastlines to reverse negative human impacts and promote new growth and niches. Our next Community Project Grant will be awarded in March – please feel free to contact me with questions about the application (or see information on page 3 of this newsletter). -

Labor in the Sculpture of Anna Hyatt Huntington

Syracuse University SURFACE Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects Projects Spring 5-1-2015 The Artist, the Workhorse: Labor in the Sculpture of Anna Hyatt Huntington Brooke Baerman Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/honors_capstone Part of the American Material Culture Commons, Art Practice Commons, Fine Arts Commons, Modern Art and Architecture Commons, Sculpture Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Baerman, Brooke, "The Artist, the Workhorse: Labor in the Sculpture of Anna Hyatt Huntington" (2015). Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects. 818. https://surface.syr.edu/honors_capstone/818 This Honors Capstone Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Artist, the Workhorse: Labor in the Sculpture of Anna Hyatt Huntington A Capstone Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Renée Crown University Honors Program at Syracuse University Brooke Baerman Candidate for a Bachelor of Arts in Art History and Renée Crown University Honors May 2015 Honors Capstone Project in Art History Capstone Project Advisor: _______________________ Sascha Scott, Professor of Art History Capstone Project Reader: _______________________ Romita Ray, Professor of Art History Honors Director: _______________________ Stephen Kuusisto, Director Date: April 22, 2015 1 Abstract Anna Hyatt Huntington (1876-1973) was an American sculptor of animals who founded the nation’s first sculpture garden, Brookgreen Gardens, in 1932. -

USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form Atalaya and Brookgreen Gardens Page #1 *********** (Rev

USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form Atalaya and Brookgreen Gardens Page #1 *********** (Rev. 8-86) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION FORM 1. Name of Property historic name: Atalaya and Brookgreen Gardens other name/site number: 2. Location street & number: U.S. Highway 17 not for publication: N/A city/town: Murrells Inlet vicinity: X state: SC county: Georgetown code: 043 zip code: 29576 3. Classification Ownership of Property: private Category of Property: district Number of Resources within Property: Contributing Noncontributing _10_ buildings _1_ sites _5_ structures _0_ objects 16 Total Number of contributing resources previously listed in the National Register: 9 Name of related multiple property listing: N/A USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form Atalaya and Brookgreen Gardens Page #2 4. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this ___ nomination ___ req'uest for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property ___ meets ___ does not meet the National Register Criteria. __ See continuation sheet. Signature of certifying official Date State or Federal agency and bureau In my opinion, the property ___ meets ___ does not meet the National Register criteria. __ See continuation sheet. Signature of commenting or other official Date State or Federal agency and bureau 5. National Park Service Certification I, hereby certify that this property is: entered in the National Register __ See continuation sheet. -

Brookgreen Gardens Set to Host Annual Art Festival Showcasing Local and National Artists and Artisans June 5 – 6 MURRELLS

Brookgreen Gardens Set to Host Annual Art Festival Showcasing Local and National Artists and Artisans June 5 – 6 MURRELLS INLET, S.C., May 27, 2021 – Brookgreen Gardens, a national historic landmark in the heart of South Carolina, is excited to announce Brookgreen Gardens Art Festival, a two-day event showcasing the fine craftsmanship of local and national artists and artisans. Paintings, sculpture, fabric art, pottery, glass, and more will be on display and available for purchase under the oaks in Brookgreen’s Live Oak Allée from June 5 – 6, 2021. “We are thrilled to offer these talented artisans a platform to showcase their craft at the Brookgreen Art Festival,” says Page Kiniry, president and CEO of Brookgreen Gardens. “The event contributes to our overall mission to support makers both locally and across the country while also allowing our community the opportunity to discover a variety of artistic gifts. From glass artists like Annie Sinton from Delaware to woodworkers like Tim Carter from Florida, there is something for every art enthusiast.” Over 68 vendors and artists from across the country, including local artisans, will gather under the canopy of 250-year-old live oak trees in Brookgreen Gardens’ Oak Allée. Guests can browse rows of photography, watercolor and pastel paintings, wooden sculptures, basketry, pottery and ceramics, fiber art, glass-blown designs, jewelry, metalwork, sculpture, oil, and acrylic paintings, and much more. Event Details: • What: Brookgreen Gardens Art Festival • When: June 5 & 6 • Where: Brookgreen Gardens, 1931 Brookgreen Drive, Murrells Inlet, SC 29576 • Price: Included with garden admission For more information about the event, visit www.brookgreen.org. -

Special 10Th Anniversary Garden Edition Page 15

21189 4/19/05 5:42 PM Page C1 RIVERBANKsRIVERBANKs May-June 2005 specialspecial 10th10th AnniversaryAnniversary gardengarden editionedition pagepage 1515 21189 4/19/05 5:42 PM Page C2 Contents Volume XXIV, Number 3 Riverbanks is published six times a year for members of Riverbanks Society by The Observation Deck 1 Riverbanks Zoological Park and Botanical Garden, Columbia, SC Plan Your Visit 2 Elephant Enlightment 4 Riverbanks Park Commission Education Adventures 8 J. Carroll Shealy, Chairman Ella Bouknight Hanging Around With Slow-Moving Sloths 12 Claudine Gee In The Know 13 Cantey Heath, Sr. Lloyd Liles Special Garden Section 15 James E. Smith Tracey Waring Robert P. Wilkins Lawrence W. Johnson, Chairman Emeritus Riverbanks Society Board of Directors H. Perry Shuping, President Jeremy G. Wilson, Vice-President Sharon Jenkins, Secretary Jan Stamps, Treasurer Stephen K. Benjamin, Esq. Joseph R. Blanchard Mike Brenan David J. Charpia Donna Croom Robert G. Davidson William H. Davidson II 12 Thomas N. Fortson Mary Howard 4 Mark D. Locke, MD, FAAP Richard N. McIntyre Dorothy G. Owen C.C. Rone, Jr. Philip Steude, MD James S. Welch Roslyn Young Don F. Barton, Director Emeritus Riverbanks Senior Staff Riverbanks Magazine Satch Krantz Dixie Kaye Allan Executive Director Executive Editor/Art Director Kim M. Benson Monique Jacobs Director of Human Resources Editor George R. Davis Ashley Walker Director of Finance Graphic Artist Ed Diebold Larry Cameron 20 Director of Animal Collections Photographer Kevin Eubanks Director of Guest Services Chris Gentile Riverbanks Hours of Operation: Director of Conservation Education Open daily 9am – 5pm Eric Helms 9am – 6pm on Saturday & Sunday, April through September Director of Facilities Management Closed Thanksgiving Day and Christmas Day Melodie Scott-Leach Special closings may be announced. -

South Carolina Coastal Zone Management Act (Pt. 2

chapter IV -------------- special management areas A. GEOGRAPHIC AREAS OF PARTICULAR CONCERN 1. Introduction Statutory Requirements The Federal Coastal Zone Management Act of 1972, while recognizing the entire coastal zone of each state as an important and vital resource, also declares that certain areas are of even more, special significance, and warrant particular attention to their preservation and development. The Act requires, in Section 305(B)(3), that each state inventory and designate the"Areas of Particular Concern" within its coastal zone as part of the state's program. Section 923.21 of the Coastal Zone Management Development and Approval Regulations (Federal Register, Vol. 44, No. 61, March 1979) defines the Federal requirements for Geographic Areas of Particular Concern (GAPCs). The subsection reads as follows: (a) Requirement. In order to meet the requirements of subsections 305(b) (3) & (5) of the Act, States must: (1) Designate geographic areas that are of particular concern, on a generic or site-specific basis or both; (2) Describe the nature of the concern and the basis on which designations are made; (3) Describe how the management program addresses and resolves the concerns for which areas are designated; and (4) Provide guidelines regarding priorities of uses in these areas, including guidelines on uses of lowest priority. The major emphasis in the GAPC segment of a coastal management program, from the Federal viewpoint, is on the adequacy of the State's authority to manage those areas or sites which have been identified. To a lesser extent, the reasons specific areas are significant as coastal resources and the criteria which establish this significance are also important for inclusion.