An Annotated Guide to African Romances, Op

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cult of Old Believers' Domestic Icons and the Beginning of Old

religions Article The Cult of Old Believers’ Domestic Icons and the Beginning of Old Belief in Russia in the 17th-18th Centuries Aleksandra Sulikowska-Bełczowska Institute of Art History, University of Warsaw, Krakowskie Przedmie´scie26/28, 00-927 Warszawa, Poland; [email protected] Received: 23 August 2019; Accepted: 11 October 2019; Published: 14 October 2019 Abstract: The aim of this paper is to present the cult of icons in the Old Believer communities from the perspective of private devotion. For the Old Believers, from the beginning of the movement, in the middle of the 17th century, icons were at the center of their religious life. They were also at the center of religious conflict between Muscovite Patriarch Nikon, who initiated the reforms of the Russian Orthodox Church, and the Old Believers and their proponent, archpriest Avvakum Petrov. Some sources and documents from the 16th and 18th centuries make it possible to analyze the reasons for the popularity of small-sized icons among priested (popovtsy) and priestless (bespopovtsy) Old Believers, not only in their private houses but also in their prayer houses (molennas). The article also shows the role of domestic icons from the middle of the 17th century as a material foundation of the identity of the Old Believers movement. Keywords: icons; private devotion; Old Believers; Patriarch Nikon; archpriest Avvakum 1. Introduction When I visited an Old Believers’ prayer house i.e., molenna for the first time I was amazed by the uncommon organization of the space. It was in 1997, in Vidzy—a village in northwestern Belarus (Sulikowska 1998, pp. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 2001, Tanglewood

SEMI OIAWA MUSIC DIRECTOR BERNARD HAITINK PRINCIPAL GUEST CONDUCTOR • i DALE CHIHULY INSTALLATIONS AND SCULPTURE / "^ik \ *t HOLSTEN GALLERIES CONTEMPORARY GLASS SCULPTURE ELM STREET, STOCKBRIDGE, MA 01262 . ( 41 3.298.3044 www. holstenga I leries * Save up to 70% off retail everyday! Allen-Edmoi. Nick Hilton C Baccarat Brooks Brothers msSPiSNEff3svS^:-A Coach ' 1 'Jv Cole-Haan v2^o im&. Crabtree & Evelyn OB^ Dansk Dockers Outlet by Designs Escada Garnet Hill Giorgio Armani .*, . >; General Store Godiva Chocolatier Hickey-Freeman/ "' ft & */ Bobby Jones '.-[ J. Crew At Historic Manch Johnston & Murphy Jones New York Levi's Outlet by Designs Manchester Lion's Share Bakery Maidenform Designer Outlets Mikasa Movado Visit us online at stervermo OshKosh B'Gosh Overland iMrt Peruvian Connection Polo/Ralph Lauren Seiko The Company Store Timberland Tumi/Kipling Versace Company Store Yves Delorme JUh** ! for Palais Royal Phone (800) 955 SHOP WS »'" A *Wtev : s-:s. 54 <M 5 "J* "^^SShfcjiy ORIGINS GAUCftV formerly TRIBAL ARTS GALLERY, NYC Ceremonial and modern sculpture for new and advanced collectors Open 7 Days 36 Main St. POB 905 413-298-0002 Stockbridge, MA 01262 Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Ray and Maria Stata Music Directorship Bernard Haitink, Principal Guest Conductor One Hundred and Twentieth Season, 2000-2001 SYMPHONY HALL CENTENNIAL SEASON Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. Peter A. Brooke, Chairman Dr. Nicholas T. Zervas, President Julian Cohen, Vice-Chairman Harvey Chet Krentzman, Vice-Chairman Deborah B. Davis, Vice-Chairman Vincent M. O'Reilly, Treasurer Nina L. Doggett, Vice-Chairman Ray Stata, Vice-Chairman Harlan E. Anderson John F. Cogan, Jr. Edna S. -

QUALM; *Quoion Answeringsystems

DOCUMENT RESUME'. ED 150 955 IR 005 492 AUTHOR Lehnert, Wendy TITLE The Process'of Question Answering. Research Report No. 88. ..t. SPONS AGENCY Advanced Research Projects Agency (DOD), Washington, D.C. _ PUB DATE May 77 CONTRACT ,N00014-75-C-1111 . ° NOTE, 293p.;- Ph.D. Dissertation, Yale University 'ERRS' PRICE NF -$0.83 1C- $15.39 Plus Post'age. DESCRIPTORS .*Computer Programs; Computers; *'conceptual Schemes; *Information Processing; *Language Classification; *Models; Prpgrai Descriptions IDENTIFIERS *QUALM; *QuOion AnsweringSystems . \ ABSTRACT / The cOmputationAl model of question answering proposed by a.lamputer program,,QUALM, is a theory of conceptual information processing based 'bon models of, human memory organization. It has been developed from the perspective of' natural language processing in conjunction with story understanding systems. The p,ocesses in QUALM are divided into four phases:(1) conceptual categorization; (2) inferential analysis;(3) content specification; and (4) 'retrieval heuristict. QUALM providea concrete criterion for judging the strengths and weaknesses'of store representations.As a theoretical model, QUALM is intended to describ general question answerinlg, where question antiering is viewed as aerbal communicb.tion. device betieen people.(Author/KP) A. 1 *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied'by EDRS are the best that can be made' * from. the original document. ********f******************************************,******************* 1, This work-was -

Final Appendices

Bibliography ADORNO, THEODOR W (1941). ‘On Popular Music’. On Record: Rock, Pop and the Written Word (ed. S Frith & A Goodwin, 1990): 301-314. London: Routledge (1publ. in Philosophy of Social Sci- ence, 9. 1941, New York: Institute of Social Research: 17-48). —— (1970). Om musikens fetischkaraktär och lyssnandets regression. Göteborg: Musikvetenskapliga in- stitutionen [On the fetish character of music and the regression of listening]. —— (1971). Sociologie de la musique. Musique en jeu, 02: 5-13. —— (1976a). Introduction to the Sociology of Music. New York: Seabury. —— (1976b) Musiksociologi – 12 teoretiska föreläsningar (tr. H Apitzsch). Kristianstad: Cavefors [The Sociology of Music – 12 theoretical lectures]. —— (1977). Letters to Walter Benjamin: ‘Reconciliation under Duress’ and ‘Commitment’. Aesthetics and Politics (ed. E Bloch et al.): 110-133. London: New Left Books. ADVIS, LUIS; GONZÁLEZ, JUAN PABLO (eds., 1994). Clásicos de la Música Popular Chilena 1900-1960. Santiago: Sociedad Chilena del Derecho de Autor. ADVIS, LUIS; CÁCERES, EDUARDO; GARCÍA, FERNANDO; GONZÁLEZ, JUAN PABLO (eds., 1997). Clásicos de la música popular chilena, volumen II, 1960-1973: raíz folclórica - segunda edición. Santia- go: Ediciones Universidad Católica de Chile. AHARONIÁN, CORIúN (1969a). Boom-Tac, Boom-Tac. Marcha, 1969-05-30. —— (1969b) Mesomúsica y educación musical. Educación artística para niños y adolescentes (ed. Tomeo). 1969, Montevideo: Tauro (pp. 81-89). —— (1985) ‘A Latin-American Approach in a Pioneering Essay’. Popular Music Perspectives (ed. D Horn). Göteborg & Exeter: IASPM (pp. 52-65). —— (1992a) ‘Music, Revolution and Dependency in Latin America’. 1789-1989. Musique, Histoire, Dé- mocratie. Colloque international organisé par Vibrations et l’IASPM, Paris 17-20 juillet (ed. A Hennion. -

UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Beyond the Limit: Gender, Sexuality, and the Animal Question in (Afro)Modernity Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0rw8q9k9 Author Jackson, Zakiyyah Iman Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Beyond the Limit: Gender, Sexuality, and the Animal Question in (Afro)Modernity by Zakiyyah Iman Jackson A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in African American Studies and the Designated Emphasis in Film Studies and the Designated Emphasis Women, Gender and Sexuality in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Abdul JanMohamed, Chair Professor Darieck Scott Professor Brandi Catanese Professor Kristen Whissel Spring 2012 Copyright Zakiyyah Iman Jackson 2012 Beyond the Limit: Gender, Sexuality, and the Animal Question in (Afro)Modernity Abstract Beyond the Limit: Gender, Sexuality, and the Animal Question in (Afro)Modernity by Zakiyyah Iman Jackson Doctor of Philosophy in African American Studies and the Designated Emphasis in Film Studies and the Designated Emphasis in Gender, Women and Sexuality University of California, Berkeley Professor Abdul JanMohamed, Chair “Beyond the Limit” provides a crucial reexamination of African diasporic literature, performance, and visual culture’s philosophical interventions into Western legal, scientific, and philosophic definitions of the human. Frederick Douglass’s speeches, Toni Morrison’s Beloved, Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God and The Pet Negro System, Charles Burnett’s The Killer of Sheep and The Horse, Jean Michel- Basquiat’s Wolf Sausage and Monkey, Ezrom Legae’s Chicken Series, and the performance art of Grace Jones both critique and displace the racializing assumptive logic that has grounded these fields’ debates on how to distinguish human identity from that of the animal. -

Nordic Race - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Nordic race - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nordic_race From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The Nordic race is one of the putative sub-races into which some late 19th- to mid 20th-century anthropologists divided the Caucasian race. People of the Nordic type were described as having light-colored (typically blond) hair, light-colored (typically blue) eyes, fair skin and tall stature, and they were empirically considered to predominate in the countries of Central and Northern Europe. Nordicism, also "Nordic theory," is an ideology of racial supremacy that claims that a Nordic race, within the greater Caucasian race, constituted a master race.[1][2] This ideology was popular in the late 19th and early 20th centuries in some Central and Northern European countries as well as in North America, and it achieved some further degree of mainstream acceptance throughout Germany via Nazism. Meyers Blitz-Lexikon (Leipzig, 1932) shows famous German war hero (Karl von Müller) as an example of the Nordic type. 1 Background ideas 1.1 Attitudes in ancient Europe 1.2 Renaissance 1.3 Enlightenment 1.4 19th century racial thought 1.5 Aryanism 2 Defining characteristics 2.1 20th century 2.2 Coon (1939) 2.3 Depigmentation theory 3 Nordicism 3.1 In the USA 3.2 Nordicist thought in Germany 3.2.1 Nazi Nordicism 3.3 Nordicist thought in Italy 3.3.1 Fascist Nordicism 3.4 Post-Nazi re-evaluation and decline of Nordicism 3.5 Early criticism: depigmentation theory 3.6 Lundman (1977) 3.7 Forensic anthropology 3.8 21st century 3.9 Genetic reality 4 See also 5 Notes 6 Further reading 7 External links Attitudes in ancient Europe 1 of 18 6/18/2013 7:33 PM Nordic race - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nordic_race Most ancient writers were from the Southern European civilisations, and generally took the view that people living in the north of their lands were barbarians. -

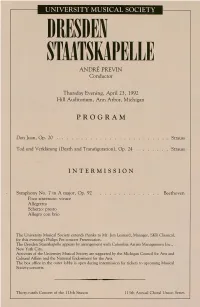

University Musical Society Program

UNIVERSITY MUSICAL SOCIETY ANDRE PREVIN Conductor Thursday Evening, April 23, 1992 Hill Auditorium, Ann Arbor, Michigan PROGRAM Don Juan, Op. 20 ........................ Strauss Tod und Verklarung (Death and Transfiguration), Op. 24 ....... Strauss INTERMISSION Symphony No. 7 in A major, Op. 92 Beethoven Poco sostenuto; vivace Allegretto Scherzo: presto Allegro con brio The University Musical Society extends thanks to Mr. Jim Leonard, Manager, SKR Classical, for this evening's Philips Pre-concert Presentation. The Dresden Staatskapelle appears by arrangement with Columbia Artists Management Inc., New York City. Activities of the University Musical Society are supported by the Michigan Council for Arts and Cultural Affairs and the National Endowment for the Arts. The box office in the outer lobby is open during intermission for tickets to upcoming Musical Society concerts. Thirty-ninth Concert of the 113th Season 113th Annual Choral Union Series Program Notes Richard Strauss (1864-1949) great success. In a letter to his father, the here was a time when the music composer wrote: "It sounded wonderful.. .No of Richard Strauss was the center where have I made a mistake in the orches of great controversy. At the end tration." Indeed, Strauss was called by the of the nineteenth century, when audience onto the stage five times, persisting the successors of Hector Berlioz, until the work was played once more. Even FranzT Liszt, and Richard Wagner were prob the staunch Brahmsian Hans von Billow ing the possibilities of new musical means and called it "a most unheard-of success." A year were discovering new potentials of poetic later, after conducting the Berlin premiere, expressiveness in music, Strauss was in the he wrote to the composer: "Your most gran vanguard of the creative search. -

Robert Walser Published Titles My Music by Susan D

Running With the Devil : Power, Gender, title: and Madness in Heavy Metal Music Music/culture author: Walser, Robert. publisher: Wesleyan University Press isbn10 | asin: 0819562602 print isbn13: 9780819562609 ebook isbn13: 9780585372914 language: English Heavy metal (Music)--History and subject criticism. publication date: 1993 lcc: ML3534.W29 1993eb ddc: 781.66 Heavy metal (Music)--History and subject: criticism. Page i Running with the Devil Page ii MUSIC / CULTURE A series from Wesleyan University Press Edited by George Lipsitz, Susan McClary, and Robert Walser Published titles My Music by Susan D. Crafts, Daniel Cavicchi, Charles Keil, and the Music in Daily Life Project Running with the Devil: Power, Gender, and Madness in Heavy Metal Music by Robert Walser Subcultural Sounds: Micromusics of the West by Mark Slobin Page iii Running with the Devil Power, Gender, and Madness in Heavy Metal Music Robert Walser Page iv WESLEYAN UNIVERSITY PRESS Published by University Press of New England, Hanover, NH 03755 © 1993 by Robert Walser All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America 5 4 3 2 1 CIP data appear at the end of the book Acknowledgments for song lyrics quoted: "Electric Eye": Words and music by Glenn Tipton, Rob Halford, and K. K. Downing, © 1982 EMI APRIL MUSIC, INC. / CREWGLEN LTD. / EBONYTREE LTD. / GEARGATE LTD. All rights controlled and administered by EMI APRIL MUSIC, INC. International copyright secured. All rights reserved. Used by permission. "Suicide Solution": Words and music by John Osbourne, Robert Daisley, and Randy Rhoads, TRO© Copyright 1981 Essex Music International, Inc. and Kord Music Publishers, New York, N.Y. -

2005 Distinguished Faculty, John Hall

The Complete Recitalist June 9-23 n Singing On Stage June 18-July 3 n Distinguished faculty John Harbison, Jake Heggie, Martin Katz, and others 2005 Distinguished Faculty, John Hall Welcome to Songfest 2005! “Search and see whether there is not some place where you may invest your humanity.” – Albert Schweitzer 1996 Young Artist program with co-founder John Hall. Songfest 2005 is supported, in part, by grants from the Aaron Copland Fund for Music and the Virgil Thomson Foundation. Songfest photography courtesy of Luisa Gulley. Songfest is a 501(c)3 corporation. All donations are 100% tax-deductible to the full extent permitted by law. Dear Friends, It is a great honor and joy for me to present Songfest 2005 at Pepperdine University once again this summer. In our third year of residence at this beautiful ocean-side Malibu campus, Songfest has grown to encompass an ever-widening circle of inspiration and achievement. Always focusing on the special relationship between singer and pianist, we have moved on from our unique emphasis on recognized masterworks of art song to exploring the varied and rich American Song. We are once again privileged to have John Harbison with us this summer. He has generously donated a commission to Songfest – Vocalism – to be premiered on the June 19 concert. Our singers and pianists will be previewing his new song cycle on poems by Milosz. Each time I read these beautiful poems, I am reminded why we love this music and how our lives are enriched. What an honor and unique opportunity this is for Songfest. -

Inforiwatfonto USERS

INFORIWATfONTO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction Is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. ProQuest Information and teaming 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 UMI' THE ART SWGS OF ANDRÉ PREVIN WITH LYRICS BY TONI MORRISON: HONEY AND RUE AND FOUR SOSGS FOR SOPRANO, CELLO AND PIANO A PERFORMER'S PERSPECTIVE D.M.A. DOCUMENT Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Misical Arts in the Graduate School of the School of The Ohio State University By Stephanie McClure Adrian, B.M., M M ***** The Ohio State University 2001 D.M.A. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 126, 2006

2006-2007 SEASON BOSTON SYM PH ORCHESTRA JAMES LEVINE MUSIC DIRECTOR BERNARD HAITINK SEIJI OZAWA MUSIC DIRECTOR LAUREATE Leaa o richer (Ue. ) i * II mmturn tin \ flftffwir " W > f John Hancock is proud to support the Boston Symphony Orchestra, the future is yours S;A« 3nl v 1 IH Hoi View from The McLean Center, Princeton, MA y . i • - j < E McLEAN CENTER AT FERNSIDE JMB^^m A comprehensive residential treatment program. So • Expertise in treating co-occurring psychiatric disorders. Highly discreet and individualized care for adults. Exceptional accommodations in a peaceful, rural setting. 'i»S -'V McLean Hospital: A Legacy of Compassionate Care Uji and Superb Clinical Treatment www.mclean.harvard.edu • 1-800-906-9531 McLean Hospital is a psychiatric teachingfacility Partners. ofHarvard Medical School, an affiliate of Healthcare Massachusetts General Hospital and a member of Partners HealthCare. REASON #75 transplan exper s It takes more than just a steady hand to perform a successful organ transplant. The highly complicated nature of these procedures demands the utmost in experience and expertise. At Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, we offer one of the most comprehensive liver, kidney and pancreas transplant programs available today. Our doctors' exceptional knowledge and skill translate to enhanced safety and care in transplant surgery - and everything that goes into it. For more information on the Transplant Center, visit www.bidmc.harvard.edu or call 1-800-667-5356. A teaching hospital of Beth Israel Deaconess Harvard Medical School Medical Center Affiliated with Joslin Clinic | A Research Partner of Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center | Official Hospital of the Boston Red Sox James Levine, Music Director Bernard Haitink, Conductor Emeritus Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Laureate 126th Season, 2006-2007 Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 115, 1995-1996, Subscription, Volume 02

BOSTON ii_'. A4 SYMPHONY . II ORCHESTRA A -+*\ SEIJIOZAWA MUSIC DIRECTOR 9 6 S E SON The security of a trust, Fidelity investment expertise. A CLjmIc Composition Just as a Beethoven score is at its Fidelity i best when performed by a world- Pergonal ** class symphony — so, too, should your trust assets be managed by Trudt r a financial company recognized Serviced globally for its investment expertise. Fidelity Investments. hat's why Fidelity now offers a naged trust or personalized estment management account ** »f -Vfor your portfolio of $400,000 or ^^ more. For more information, visit -a Fidelity Investor Center or call Fidelity Pergonal Triut Serviced at 1-800-854-2829. Visit a Fidelity Investor Center Near You: Boston - Back Bay • Boston - Financial District Braintree, MA • Burlington, MA Fidelity Investments" SERVICES OFFERED ONLY THROUGH AUTHORIZED TRUST COMPANIES. TRUST SERVICES VARY BY STATE. FIDELITY BROKERAGE SERVICES, INC., MEMBER NYSE, SIPC. Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Bernard Haitink, Principal Guest Conductor One Hundred and Fifteenth Season, 1995-96 Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. J. P. Barger, Chairman Nicholas T. Zervas, President Peter A. Brooke, Vice-Chairman Harvey Chet Krentzman, Vice-Chairman Mrs. Edith L. Dabney, Vice-Chairman William J. Poorvu, Vice-Chairman and Treasurer Mrs. John H. Fitzpatrick, Vice-Chairman Ray Stata, Vice-Chairman Harlan E. Anderson Nader F. Darehshori Edna S. Kalman Mrs. Robert B. Newman James F. Cleary Deborah B. Davis Allen Z. Kluchman Robert P. O'Block John E. Cogan, Jr. Nina L. Doggett George Krupp Peter C. Read Julian Cohen Avram J. Goldberg R. Willis Leith, Jr. Carol Scheifele-Holmes William F.