Mobbing Behaviour Varies According to Predator Dangerousness Andᅡᅠoccurrence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wallcreeper and the Camargue

Wallcreeper and The Camargue Naturetrek Tour Report 19 – 23 November 2018 Firecrest Western Swamphen Stripeless Tree Frog Spoonbill Report compiled by Matt Collis Images courtesy of Neil McMahon Naturetrek Mingledown Barn Wolf's Lane Chawton Alton Hampshire GU34 3HJ UK T: +44 (0)1962 733051 E: [email protected] W: www.naturetrek.co.uk Tour Report Wallcreepers and The Camargue Tour participants: Matt Collis & Neil McMahon (leaders) with 16 Naturetrek clients Summary A short birding trip to the very special Camargue district of southern France provides an excellent opportunity to experience good views of typical waterbirds of the west Mediterranean. Utilising a family-run hotel on the outskirts of the ancient city of Arles as our base, the itinerary provided an easy opportunity to look for flamingoes, herons and wading birds using the shallow waters and reed-fringed lagoons as a breeding area or a suitable stop-over for migrants. The mountainous areas attract different and more localized species and we located special birds such as Wallcreeper, Rock Sparrow and Booted Eagle, together with a selection of other stunning species that call the Camargue home. Day 1 Monday 19th November Arriving in the early evening, leaders Neil and Matt met 15 of the 16 clients at Marseille airport, before collecting the minibuses and beginning the journey to the hotel. French protests and road blocks meant the route was more cross country but after just over an hour or so we arrived at our destination, Hotel des Granges. We were greeted by Bruno and Marie-Jo, our wonderful hosts and owners of this classically French Hotel, and a lone Black Redstart, the first bird for our trip, sat roosting over the entrance porch. -

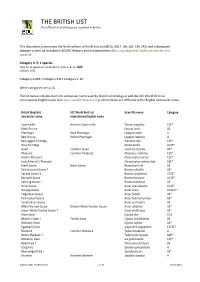

THE BRITISH LIST the Official List of Bird Species Recorded in Britain

THE BRITISH LIST The official list of bird species recorded in Britain This document summarises the Ninth edition of the British List (BOU, 2017. Ibis 160: 190-240) and subsequent changes to the List included in BOURC Reports and announcements (bou.org.uk/british-list/bourc-reports-and- papers/). Category A, B, C species Total no. of species on the British List (Cats A, B, C) = 623 at 8 June 2021 Category A 605 • Category B 8 • Category C 10 Other categories see p.13. The list below includes both the vernacular name used by British ornithologists and the IOC World Bird List international English name (see www.worldbirdnames.org) where these are different to the English vernacular name. British (English) IOC World Bird List Scientific name Category vernacular name international English name Capercaillie Western Capercaillie Tetrao urogallus C3E* Black Grouse Lyrurus tetrix AE Ptarmigan Rock Ptarmigan Lagopus muta A Red Grouse Willow Ptarmigan Lagopus lagopus A Red-legged Partridge Alectoris rufa C1E* Grey Partridge Perdix perdix AC2E* Quail Common Quail Coturnix coturnix AE* Pheasant Common Pheasant Phasianus colchicus C1E* Golden Pheasant Chrysolophus pictus C1E* Lady Amherst’s Pheasant Chrysolophus amherstiae C6E* Brent Goose Brant Goose Branta bernicla AE Red-breasted Goose † Branta ruficollis AE* Canada Goose ‡ Branta canadensis AC2E* Barnacle Goose Branta leucopsis AC2E* Cackling Goose † Branta hutchinsii AE Snow Goose Anser caerulescens AC2E* Greylag Goose Anser anser AC2C4E* Taiga Bean Goose Anser fabalis AE* Pink-footed Goose Anser -

Progress in the Development of an Eurasian-African Bird Migration Atlas

CONVENTION ON UNEP/CMS/COP13/Inf.20 MIGRATORY 10 February 2020 SPECIES Original: English 13th MEETING OF THE CONFERENCE OF THE PARTIES Gandhinagar, India, 17 - 22 February 2020 Agenda Item 25 PROGRESS IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF AN EURASIAN-AFRICAN BIRD MIGRATION ATLAS (Submitted by the European Union of Bird Ringing (EURING) and the Institute of Avian Research) Summary: The African-Eurasian Bird Migration Atlas is being developed under the auspices of CMS in the framework of a Global Animal Migration Atlas, of which it constitutes a module. The African-Eurasian Bird Migration Atlas is being developed and compiled by the European Union of Bird Ringing (EURING) under a Project Cooperation Agreement (PCA) between the CMS Secretariat and the Institute of Avian Research, acting on behalf of EURING. The development of the African-Eurasian Bird Migration Atlas is funded with the contribution granted by the Government of Italy under the Migratory Species Champion Programme. This information document includes a progress report on the development of the various components of the project. The project is expected to be completed in 2021. UNEP/CMS/COP13/Inf.20 Eurasian-African Bird Migration Atlas progress report February 2020 Stephen Baillie1, Franz Bairlein2, Wolfgang Fiedler3, Fernando Spina4, Kasper Thorup5, Sam Franks1, Dorian Moss1, Justin Walker1, Daniel Higgins1, Roberto Ambrosini6, Niccolò Fattorini6, Juan Arizaga7, Maite Laso7, Frédéric Jiguet8, Boris Nikolov9, Henk van der Jeugd10, Andy Musgrove1, Mark Hammond1 and William Skellorn1. A report to the Convention on Migratory Species from the European Union for Bird Ringing (EURING) and the Institite of Avian Research, Wilhelmshaven, Germany 1. British Trust for Ornithology, Thetford, IP24 2PU, UK 2. -

Birds, Butterflies & Wildflowers of the Dordogne

Tour Report France – Birds, Butterflies & Wildflowers of the Dordogne 15 – 22 June 2019 Woodchat shrike Lizard orchid Spotted fritillary (female) River Dordogne near Lalinde Compiled by David Simpson & Carine Oosterlee Images courtesy of: Mike Stamp & Corine Oosterlee 01962 302086 [email protected] www.wildlifeworldwide.com Tour Leaders: David Simpson & Corine Oosterlee Day 1: Arrive Bergerac; travel to Mauzac & short local walk Saturday 15 June 2019 It was a rather cool, cloudy and breezy afternoon as the Ryanair flight touched down at Bergerac airport. Before too long the group had passed through security and we were meeting one another outside the arrivals building. There were only five people as two of the group had driven down directly to the hotel in Mauzac, from their home near Limoges in the department of Haute-Vienne immediately north of Dordogne. After a short walk to the minibus we were soon heading off through the fields towards Mauzac on the banks of the River Dordogne. A song thrush sang loudly as we left the airport and some of us had brief views of a corn bunting or two on the airport fence, whilst further on at the Couze bridge over the River Dordogne, several crag martins were flying. En route we also saw our first black kites and an occasional kestrel and buzzard. We were soon parking up at the Hotel Le Barrage where Amanda, the hotel manager, greeted us, gave out room keys and helped us with the suitcases. Here we also met the other couple who had driven straight to the hotel (and who’d already seen a barred grass snake along the riverbank). -

SEO/BIRDLIFE BIRD MONITORING PROGRAMMES 2012 2 Our Volunteers’ Contribution

SEO/BIRDLIFE BIRD MONITORING PROGRAMMES 2012 2 Our volunteers’ contribution 4 Sacre programme OUR VOLUNTEERS’ CONTRIBUTION Bird trends in spring 10 Sacin programme Bird trends in winter Thanks to the contribution of our volunteers we are able to take on large-scale projects, as it would be difficult to recruit profes- sional staff for this work. The value of this contribution does not only reside in the scale or scope that can be given to the work. It is 12 Sacre / Sacin also an economic question– the economic value of our volunteers’ Common bird trends in National Parks work is almost never quantified. It is not difficult to calculate a minimum economic value of our vol- unteers’ contribution to each monitoring programme, census and atlas. It is also worthwhile to know its relevance in the understand- 14 Noctua programme ing of the state of biodiversity in our country. Nocturnal bird trends Each participant in any SEO/BirdLife monitoring programme (Sacre, Sacin or Noctua) must visit the field once or twice prior to sampling. They also need to design the work in hand well, which involves some “office” hours – a good job depends on a good de- sign. Thus, they need to invest some time in checking digital or any 16 Paser programme Bird ringing in spring other type of map, to consult and calculate things difficult to ap- preciate in the field, or to have an overview of the sampling area, the itineraries or the distribution of the points. This previous work, at home and in the field, also involves hours or even days in visits to the countryside and fieldwork. -

Madeira Cujos Registos Requerem Homologação Pelo Cpr

LISTA REGIONAL DAS ESPÉCIES DE AVES RARAS OU ACIDENTAIS PARA A MADEIRA CUJOS REGISTOS REQUEREM HOMOLOGAÇÃO PELO CPR RARE OR ACCIDENTAL SPECIES CONSIDERED FOR MADEIRA ARCHIPELAGO BY THE PRC Notas: Apenas espécies com registos publicados ou com espécimes em museus foram consideradas para inclusão. A área abrangida inclui as ilhas da Madeira e Porto Santo, e os arquipélagos das Desertas e das Selvagens e as ZEEs respectivas. Esta lista pretende reunir o conjunto de espécies consideradas como raras ou acidentais somente à escala regional. Todas as espécies ou subespécies registadas pela primeira vez na Madeira (e não elencadas nesta lista) estão sujeitas a homologação pelo CPR. * Note: Only species for which published records or museum specimens are known to exist have been considered for inclusion in this list. The area covered includes the islands of Madeira and Porto Santo, and the Desertas and Selvagens archipelagos and their EEZ. This list aims to present the group of species considered rare or vagrant at a regional scale only. Furthermore, details of all species and subspecies recorded in Madeira for the first time are also subject to review by the PRC. MADEIRA NOME CIENTÍFICO NOME PORTUGUÊS ENGLISH NAME Branta bernicla Ganso-de-faces-pretas Brent Goose Anser anser Ganso-bravo Greylag Goose Tadorna tadorna Tadorna Common Shelduck Spatula querquedula Marreco Garganey Spatula clypeata Pato-colhereiro Northern Shoveler Mareca strepera Frisada Gadwall Mareca penelope Piadeira-comum Eurasian Wigeon Anas acuta Arrábio Northern Pintail Aythya -

Regulus Ignicapilla

Regulus ignicapilla -- (Temminck, 1820) ANIMALIA -- CHORDATA -- AVES -- PASSERIFORMES -- REGULIIDAE Common names: Firecrest; European Red List Assessment European Red List Status LC -- Least Concern, (IUCN version 3.1) Assessment Information Year published: 2015 Date assessed: 2015-03-31 Assessor(s): BirdLife International Reviewer(s): Symes, A. Compiler(s): Ashpole, J., Burfield, I., Ieronymidou, C., Pople, R., Wheatley, H. & Wright, L. Assessment Rationale European regional assessment: Least Concern (LC) EU27 regional assessment: Least Concern (LC) At both European and EU27 scales this species has an extremely large range, and hence does not approach the thresholds for Vulnerable under the range size criterion (Extent of Occurrence 10% in ten years or three generations, or with a specified population structure). The population trend appears to be stable, and hence the species does not approach the thresholds for Vulnerable under the population trend criterion (30% decline over ten years or three generations). For these reasons the species is evaluated as Least Concern within both Europe and the EU27. Occurrence Countries/Territories of Occurrence Native: Albania; Andorra; Austria; Belarus; Belgium; Bosnia and Herzegovina; Bulgaria; Croatia; Czech Republic; Denmark; France; Germany; Greece; Hungary; Italy; Latvia; Liechtenstein; Lithuania; Macedonia, the former Yugoslav Republic of; Malta; Montenegro; Netherlands; Poland; Portugal; Russian Federation; Serbia; Slovakia; Slovenia; Spain; Sweden; Switzerland; Turkey; Ukraine; United Kingdom; Gibraltar (to UK) Origin Uncertain: Azerbaijan Population The European population is estimated at 4,180,000-7,110,000 pairs, which equates to 8,360,000-14,200,000 mature individuals. The population in the EU27 is estimated at 3,800,000-6,550,000 pairs, which equates to 7,610,000-13,100,000 mature individuals. -

AERC Wplist July 2015

AERC Western Palearctic list, July 2015 About the list: 1) The limits of the Western Palearctic region follow for convenience the limits defined in the “Birds of the Western Palearctic” (BWP) series (Oxford University Press). 2) The AERC WP list follows the systematics of Voous (1973; 1977a; 1977b) modified by the changes listed in the AERC TAC systematic recommendations published online on the AERC web site. For species not in Voous (a few introduced or accidental species) the default systematics is the IOC world bird list. 3) Only species either admitted into an "official" national list (for countries with a national avifaunistic commission or national rarities committee) or whose occurrence in the WP has been published in detail (description or photo and circumstances allowing review of the evidence, usually in a journal) have been admitted on the list. Category D species have not been admitted. 4) The information in the "remarks" column is by no mean exhaustive. It is aimed at providing some supporting information for the species whose status on the WP list is less well known than average. This is obviously a subjective criterion. Citation: Crochet P.-A., Joynt G. (2015). AERC list of Western Palearctic birds. July 2015 version. Available at http://www.aerc.eu/tac.html Families Voous sequence 2015 INTERNATIONAL ENGLISH NAME SCIENTIFIC NAME remarks changes since last edition ORDER STRUTHIONIFORMES OSTRICHES Family Struthionidae Ostrich Struthio camelus ORDER ANSERIFORMES DUCKS, GEESE, SWANS Family Anatidae Fulvous Whistling Duck Dendrocygna bicolor cat. A/D in Morocco (flock of 11-12 suggesting natural vagrancy, hence accepted here) Lesser Whistling Duck Dendrocygna javanica cat. -

A Method to Enhance Species Knowledge NAME ILLUSTRATIONS

5-MIN-BIOLOGY a method to enhance species knowledge Jonathan Hense & Annette Scheersoi Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-University Bonn, Biology Education BACKGROUND Biodiversity loss and its impact on humanity is one of the key challenges of the 21st century (e.g. CARDINALE et al., 2012). This problem is even more aggravated by the loss of spe- EXAMPLE OF A 5-MIN-BIOLOGY ON cies knowledge in society and also in science (e.g. FROBEL & COMMON BIRDS SCHLUMPRECHT, 2016; RSPB, 2017). This extinction of the ex- perience (expert knwoledge) has a strong effect as species Conducted in a regular university seminar presenting the following species: knowledge is a prerequisite for the research on biodiversi- 1. Common chiffchaff 8. Common firecrest ty loss and therefore for conservation approaches (MILLER, Phylloscopus collybita Regulus ignicapillus 2005; COX & GASTON, 2015). 2. Common chaffinch 9. Common redstart GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS Fringilla coelebs Phoenicurus phoenicurus 3. Short-toed treecreeper 10. Song thrush The method was developed by ALPHONS BEILER (1965) and Certhia brachydactyla Turdus philomelos redefined by STICHMANN (1992) and describes a short (5 mi- 4. Great tit 11. Blackbird nutes) off-topic and repetitive period at the beginning of a Parus major Turdus merula regular teaching situation, which can be used to either take 5. Blue tit 12. Eurasian blackcap up issues of the audience‘s current interest or to develop Parus caeruleus Sylvia atricapilla species knowledge. 6. Eurasian nuthatch 13. European robin The method was originally developed for a school setting, Sitta europaea Erithacus rubecula but it is also applicable for the university context. 7. Great spotted woodpecker 14. -

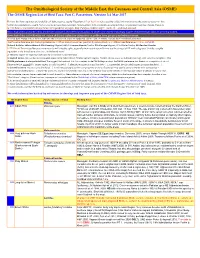

OSME List V3.4 Passerines-2

The Ornithological Society of the Middle East, the Caucasus and Central Asia (OSME) The OSME Region List of Bird Taxa: Part C, Passerines. Version 3.4 Mar 2017 For taxa that have unproven and probably unlikely presence, see the Hypothetical List. Red font indicates either added information since the previous version or that further documentation is sought. Not all synonyms have been examined. Serial numbers (SN) are merely an administrative conveninence and may change. Please do not cite them as row numbers in any formal correspondence or papers. Key: Compass cardinals (eg N = north, SE = southeast) are used. Rows shaded thus and with yellow text denote summaries of problem taxon groups in which some closely-related taxa may be of indeterminate status or are being studied. Rows shaded thus and with white text contain additional explanatory information on problem taxon groups as and when necessary. A broad dark orange line, as below, indicates the last taxon in a new or suggested species split, or where sspp are best considered separately. The Passerine Reference List (including References for Hypothetical passerines [see Part E] and explanations of Abbreviated References) follows at Part D. Notes↓ & Status abbreviations→ BM=Breeding Migrant, SB/SV=Summer Breeder/Visitor, PM=Passage Migrant, WV=Winter Visitor, RB=Resident Breeder 1. PT=Parent Taxon (used because many records will antedate splits, especially from recent research) – we use the concept of PT with a degree of latitude, roughly equivalent to the formal term sensu lato , ‘in the broad sense’. 2. The term 'report' or ‘reported’ indicates the occurrence is unconfirmed. -

EUROPEAN BIRDS of CONSERVATION CONCERN Populations, Trends and National Responsibilities

EUROPEAN BIRDS OF CONSERVATION CONCERN Populations, trends and national responsibilities COMPILED BY ANNA STANEVA AND IAN BURFIELD WITH SPONSORSHIP FROM CONTENTS Introduction 4 86 ITALY References 9 89 KOSOVO ALBANIA 10 92 LATVIA ANDORRA 14 95 LIECHTENSTEIN ARMENIA 16 97 LITHUANIA AUSTRIA 19 100 LUXEMBOURG AZERBAIJAN 22 102 MACEDONIA BELARUS 26 105 MALTA BELGIUM 29 107 MOLDOVA BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA 32 110 MONTENEGRO BULGARIA 35 113 NETHERLANDS CROATIA 39 116 NORWAY CYPRUS 42 119 POLAND CZECH REPUBLIC 45 122 PORTUGAL DENMARK 48 125 ROMANIA ESTONIA 51 128 RUSSIA BirdLife Europe and Central Asia is a partnership of 48 national conservation organisations and a leader in bird conservation. Our unique local to global FAROE ISLANDS DENMARK 54 132 SERBIA approach enables us to deliver high impact and long term conservation for the beneit of nature and people. BirdLife Europe and Central Asia is one of FINLAND 56 135 SLOVAKIA the six regional secretariats that compose BirdLife International. Based in Brus- sels, it supports the European and Central Asian Partnership and is present FRANCE 60 138 SLOVENIA in 47 countries including all EU Member States. With more than 4,100 staf in Europe, two million members and tens of thousands of skilled volunteers, GEORGIA 64 141 SPAIN BirdLife Europe and Central Asia, together with its national partners, owns or manages more than 6,000 nature sites totaling 320,000 hectares. GERMANY 67 145 SWEDEN GIBRALTAR UNITED KINGDOM 71 148 SWITZERLAND GREECE 72 151 TURKEY GREENLAND DENMARK 76 155 UKRAINE HUNGARY 78 159 UNITED KINGDOM ICELAND 81 162 European population sizes and trends STICHTING BIRDLIFE EUROPE GRATEFULLY ACKNOWLEDGES FINANCIAL SUPPORT FROM THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION. -

Trip Report May 11 – 23, 2019 |Written by Carlos Sanchez

Spain: Birding & Nature | Trip Report May 11 – 23, 2019 |Written by Carlos Sanchez Guide: Carlos Sanchez, with 6 participants: Christine, Laura, Brad, Cathy, Elizabeth, & Richard Naturalist Journeys, LLC | Caligo Ventures PO Box 16545 Portal, AZ 85632 PH: 520.558.1146 | 866.900.1146 Fax 650.471.7667 naturalistjourneys.com | caligo.com [email protected] | [email protected] Sat., May 11 Arrivals in Madrid | Gredos After meeting at our comfortable hotel in Madrid at around 9 a.m. we began our journey west through the city of Madrid towards the alpine scenery of the Gredos Mountains. After about an hour’s drive, we made our first stop at the Bulls of Guisando. The four ancient granite sculptures were built by an ancient Celtiberian tribe around the 2nd century BCE. They are a recurrent feature in Spanish literature, including the novel Dox Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes. As it was spring, the surrounding riparian woodlands rang with the calls of nesting birds such as Cetti’s Warbler, Common Nightingale, and we saw our first European Bee-eaters flying overhead. After an incredible lunch overlooking a forested valley, we continued onwards to Puerto del Pico in the Sierra de Gredos. This mountain pass, at about 4,600 ft, was already far above the tree line (the tree line is surprisingly low in Spain), and we could clearly see an ancient Roman road stretching out before us–still in excellent condition even after two millennia. A little patch of trees in the parking lot held our first Great and Blue Tit, as well as our first Common Firecrest.