Sovereignty, Governmentality and Development in Ayub's Pakistan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Training Schedule 2018.Xlsx

Training Schedule for Successful Hajj Applicants of Government Hajj Scheme - 2018 Sr. No. District Date Venue Time Training Arranged By JALAL BABA AUDITORIUM, Hajji Camp, Islamabad, Ph: (051) 1 ABBOTTABAD 25-Mar-18 09 AM ABBOTTABAD 9247521, 9247575 JALAL BABA AUDITORIUM, Hajji Camp, Islamabad, Ph: (051) 2 ABBOTTABAD 26-Mar-18 09 AM ABBOTTABAD 9247521, 9247575 PARADISE MARRIAGE HALL, MAIN Hajji Camp, Islamabad, Ph: (051) 3 ATTOCK 28-Mar-18 09 AM RAWALPINDI ROAD, FATEH JANG 9247521, 9247575 TULIP MARQUE, CHINA CHOWK, Hajji Camp, Islamabad, Ph: (051) 4 ATTOCK 03-Apr-18 09 AM HAJI SHAH ROAD, ATTOCK 9247521, 9247575 Hajj Complex, Quetta, Ph: (081) 5 AWARAN 19-Apr-18 DISTRICT COUNCIL HALL, PANJGUR 09 AM 9213021, 9213326 QATAR MASJID, HYDERABAD Hajji Camp, Karachi, Ph: (021) 6 BADIN 28-Mar-18 10 AM ROAD, BADIN 99204761, 35688307 MILAN MARRIEGE CLUB, SUGER 7 BAHAWAL NAGAR 02-Apr-18 09 AM Hajji Camp, Multan, Ph: (061) 9330058 MILL ROAD,CHISHTIAN 8 BAHAWAL NAGAR 03-Apr-18 OFFICERS CLUBE FORT ABBAS 09 AM Hajji Camp, Multan, Ph: (061) 9330058 INSAF MARRIAGE HALL OPPOSITE TABLEEGHI MARKAN 9 BAHAWAL NAGAR 04-Apr-18 09 AM Hajji Camp, Multan, Ph: (061) 9330058 HAROONABAD ROAD , BAHAWAL NAGHAR MILAN MARRIEGE CLUB, SUGER 10 BAHAWALPUR 02-Apr-18 09 AM Hajji Camp, Multan, Ph: (061) 9330058 MILL ROAD,CHISHTIAN QUAID-E-AZAM MEDICAL 11 BAHAWALPUR 06-Apr-18 09 AM Hajji Camp, Multan, Ph: (061) 9330058 COLLEGE, BAHAWAL PUR. QUAID-E-AZAM MEDICAL 12 BAHAWALPUR 07-Apr-18 09 AM Hajji Camp, Multan, Ph: (061) 9330058 COLLEGE, BAHAWAL PUR. -

National Electric Power Regulatory Authority Islamic Republic of Pakistan

National Electric Power Regulatory Authority Islamic Republic of Pakistan NEPRA Tower, Attaturk Avenue (East), G-511, Islamabad Ph: +92-51-9206500, Fax: +92-51-2600026 Web: www.nepra.org.pk, E-mail: [email protected] No. NEPRA/ADG(L)/LAN-2187/ / 6 Y 2 1- (3 September 17 2019 Mr. Zafar Aitmad Siddique, R-3, Block-1, Gulistan-e-Johar, Karachi, Phone No. 0301-8258533 Subject: Generation Licence No. DGL/2187/2019 Licence Application No. LAN-2187 Mr. Zafar Aitmad Siddique, K — Electric Limited Ref KEL's letter No. KE/BPR/NEPRA/2019/624 dated 23.07.2019 (received on 29.07.2019) Enclosed please find herewith Generation Licence No. DGL/2187/2019 granted by the National Electric Power Regulatory Authority to Mr. Zafar Aitmad Siddique for 05.20 kW photo voltaic solar based distributed generation facility located at R-3, Block-1, Gulistan-e-Johar, Karachi, under NEPRA (Alternative & Renewable Energy) Distributed Generation and Net Metering Regulations, 2015. 2. Please quote above mentioned Generation ence No. for future correspondence. Enclosure: Generation Licence (DGL/2187/2019) CA (Syed Safeer Hussain) Copy to: 1. Chief Executive Office, Alternative Energy Development Board, 2nd Floor, OPF Building, G-5/2, Islamabad. 2. Chief Executive Officer, K-Electric Limited, KE House, 39 B, Main Sunset Boulevard, DHA Phase-II, Karachi. 3. Director General, Environment Protection Department, Government of Sindh, Complex Plot No. ST-2/1, Korangi Industrial Area, Karachi. National Electric Power f equlatory Authority NEP Is! mabad— kistan The Authority hereby grants Generation Licence to Mr. Zafar Aitvpad Siddique, for 5.20 KW photovoltaic solar based distributed generation facility, having consumer reference number LA912022, located at R-3, Block-I, Gulistan-e- Jouhar, Karachi under the National Electric Power Regulatory Authority (Alternative & Renewable Energy) Distributed Generation and Net Metering Regulations, 2015 (the "A&RE Regulations") for a period of seven (07) years. -

Group Identity and Civil-Military Relations in India and Pakistan By

Group identity and civil-military relations in India and Pakistan by Brent Scott Williams B.S., United States Military Academy, 2003 M.A., Kansas State University, 2010 M.M.A., Command and General Staff College, 2015 AN ABSTRACT OF A DISSERTATION submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Security Studies College of Arts and Sciences KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2019 Abstract This dissertation asks why a military gives up power or never takes power when conditions favor a coup d’état in the cases of Pakistan and India. In most cases, civil-military relations literature focuses on civilian control in a democracy or the breakdown of that control. The focus of this research is the opposite: either the returning of civilian control or maintaining civilian control. Moreover, the approach taken in this dissertation is different because it assumes group identity, and the military’s inherent connection to society, determines the civil-military relationship. This dissertation provides a qualitative examination of two states, Pakistan and India, which have significant similarities, and attempts to discern if a group theory of civil-military relations helps to explain the actions of the militaries in both states. Both Pakistan and India inherited their military from the former British Raj. The British divided the British-Indian military into two militaries when Pakistan and India gained Independence. These events provide a solid foundation for a comparative study because both Pakistan’s and India’s militaries came from the same source. Second, the domestic events faced by both states are similar and range from famines to significant defeats in wars, ongoing insurgencies, and various other events. -

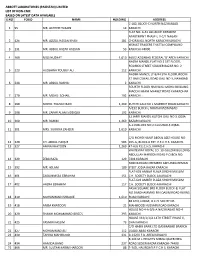

Abbott Laboratories (Pakistan) Limited List of Non-Cnic Based on Latest Data Available S.No Folio Name Holding Address 1 95

ABBOTT LABORATORIES (PAKISTAN) LIMITED LIST OF NON-CNIC BASED ON LATEST DATA AVAILABLE S.NO FOLIO NAME HOLDING ADDRESS C-182, BLOCK-C NORTH NAZIMABAD 1 95 MR. AKHTER HUSAIN 14 KARACHI FLAT NO. A-31 ALLIANCE PARADISE APARTMENT PHASE-I, II-C/1 NAGAN 2 126 MR. AZIZUL HASAN KHAN 181 CHORANGI, NORTH KARACHI KARACHI. KISMAT TRADERS THATTAI COMPOUND 3 131 MR. ABDUL RAZAK HASSAN 53 KARACHI-74000. 4 169 MISS NUZHAT 1,610 469/2 AZIZABAD FEDERAL 'B' AREA KARACHI NAZRA MANZIL FLAT NO 2 1ST FLOOR, RODRICK STREET SOLDIER BAZAR NO. 2 5 223 HUSSAINA YOUSUF ALI 112 KARACHI NADIM MANZIL LY 8/44 5TH FLOOR, ROOM 37 HAJI ESMAIL ROAD GALI NO 3, NAYABAD 6 244 MR. ABDUL RASHID 2 KARACHI FOURTH FLOOR HAJI WALI MOHD BUILDING MACCHI MIANI MARKET ROAD KHARADHAR 7 270 MR. MOHD. SOHAIL 192 KARACHI 8 290 MOHD. YOUSUF BARI 1,269 KUTCHI GALI NO 1 MARRIOT ROAD KARACHI A/192 BLOCK-L NORTH NAZIMABAD 9 298 MR. ZAFAR ALAM SIDDIQUI 192 KARACHI 32 JAFRI MANZIL KUTCHI GALI NO 3 JODIA 10 300 MR. RAHIM 1,269 BAZAR KARACHI A-113 BLOCK NO 2 GULSHAD-E-IQBAL 11 301 MRS. SURRIYA ZAHEER 1,610 KARACHI C/O MOHD HANIF ABDUL AZIZ HOUSE NO. 12 320 CH. ABDUL HAQUE 583 265-G, BLOCK-6 EXT. P.E.C.H.S. KARACHI. 13 327 AMNA KHATOON 1,269 47-A/6 P.E.C.H.S. KARACHI WHITEWAY ROYAL CO. 10-GULZAR BUILDING ABDULLAH HAROON ROAD P.O.BOX NO. 14 329 ZEBA RAZA 129 7494 KARACHI NO8 MARIAM CHEMBER AKHUNDA REMAN 15 392 MR. -

Politics of Combined Opposition Parties (Cop) During Ayub Khan Era (1958-1969)

Journal of the Punjab University Historical Society Volume No. 31, Issue No. 1, January - June 2018 Akhtar Hussain * Politics of Combined Opposition Parties (Cop) During Ayub Khan Era (1958-1969) Abstract This Paper is about the Combined Opposition Parties, an electoral alliance which challenged Ayub Khan in the 1965 Presidential election. The alliance not only challenged but it gave a tough time through its effective mass mobilisation both in the urban and rural areas to one of the strongest military ruler in Pakistan. The alliance played a vital role in initiating critical debate and discussion in place of dead conformism, in rekindling and refurbishing the enfeebled and dying flame of democracy in Pakistan and thus setting the nation a new towards a democratic destiny. Furthermore this alliance made a female as its candidate for Presidentship which is a debatable issue among the orthodox Muslim scholars and religio-political parties of the country. The paper focuses on the political background, formation, strategies and politics of COP to get rid of the military ruler. The paper is mainly descriptive in approach yet partial analytical approach is also employed. Both primary and secondary sources of information are used in this article. Key Words: Democracy, Alliance politics, Military rule, Opposition politics, Political parties, Election. Introduction: Ayub Khan came into power after imposition of martial law in the country in October 1958. 1 He assured the nation about lifting of martial law with the fulfilment of its objectives i.e. removal of all the political, social, economic and administrative confusions that prevailed in the country.2 He banned all the Political parties, their offices were sealed and their capital was confiscated as according to him, “…the politicians had ruined the country through their corrupt practices”.3 In the first couple of years, he paid attention towards administration of the country and strengthening his rule. -

Tormenting 71 File-04

The dead bodies of the students of Sergent Zahurul Huq Hall, Dhaka University, Killed during the dark night on March 25, 1971 A visual document of Pakistan army's atrocities in the district of Kushtia An ice berg of brutal women repression by the Pakistani occupied forces which become a regular phenomenon during nine months of Bangladesh liberation war Two repressed women at the Rehabilitation Centre in Dhaka during 1972 The bodies of the intellectuals at Rayer Bazar slaughtering spot. Apprehending ultimate defeat, the Pakistani occupied forces prepared list of the top most intellectuals of the country with the help of their local collaborator Jamaat-e-Islami's killing squad Al Badar and executed the pre-planned elimination A example of crime against humanity: Pakistani soldiers used to humilate people in this manner to identify whether he is a Hindu or Muslim The bodies of innocent Bengalees on the street of Jessore district Dhaka city wore a vies of devastation : aftermath of the March 25 crack down in 1971 Indian Army preparing lists of the sophisticated arms laid down by Pakistani occupied forces on December 16, 1971 The agony of a women in a west Bengal refugee camp in India whose husband and others family members were killed by Pakistani army The human skeletons recovered from the slaughtered sites. More than 5 thousands such sites are calculated in different part of Bangladesh The thousands of localities were destroyed by Pakistani shells leaving hundreds dead or jnjured. A bid for treatment of a burnt boy The wailing parents at a refugee camp in Indian state of West Bengal, who lost their children Appendix List of the war criminals of Pakistani armed forces Bangladesh government prepared a list of five hundred Pakistani war criminals in 1972. -

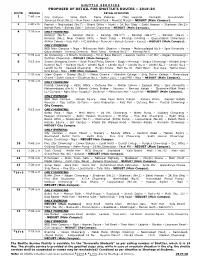

Shuttle Route

SHUTTLE SERVICES PROPOSED OF DETAIL FOR SHUTTLE’S ROUTES – 2019-20 ROUTE TIMINGS DETAIL OF ROUTES 1 7:40 a.m City Campus – Jama Cloth – Radio Pakistan – 7Day Hospital – Numaish – Gurumandir – Jamshed Road (No.3) – New Town – Askari Park – Mumtaz Manzil – NEDUET (Main Campus). 2 7:40 a.m Paposh – Nazimabad (No.7) – Board Office – Hydri – 2K Bus Stop – Sakhi Hassan – Shadman (No.2)– Namak Bank – Sohrab Goth – Gulshan Chowrangi – NEDUET (Main Campus). 4 7:20 a.m ONLY MORNING: Korangi (No.5) – Korangi (No.4) – Korangi (No.31/2) – Korangi (No.21/2) – Korangi (No.2) – Korangi (No.1, Near Chakra Goth) – Nasir Jump – Korangi Crossing – Qayyumabad Chowrangi – Akhtar Colony – Kala Pull – FTC Building – Nursery – Baloch Colony – Karsaz – NEDUET (Main Campus). ONLY EVENING: NED Main Campus – Nipa – Millennium Mall– Stadium – Karsaz – Mehmoodabad No.6 – Iqra University – Qayyumabad – Korangi Crossing – Nasir Jump – Korangi No.21/2 – Korangi No.5. 5 7:45 a.m 4K Chowrangi – 2 Minute Chowrangi – 5C-4 (Bara Market) – Saleem Centre – U.P Mor – Nagan Chowrangi – Gulshan Chowrangi – NEDUET (Main Campus). 6 7:15 a.m Shama Shopping Centre – Shah Faisal Police Station – Bagh-e-Korangi – Singer Chowrangi – Khaddi Stop – Korangi No.5 – Korangi No.6 – Landhi No.6 – Landhi No.5 – Landhi No.4 – Landhi No.3 – Landhi No.1 – Landhi No.89 – Dawood Chowrangi – Murghi Khana – Malir No.15 – Malir Hault – Star Gate – Natha Khan – Drig Road – Nipa – NED Main Campus. 7 7:35 a.m Islam Chowk – Orangi (No.5) – Metro Cinema – Abdullah College – Ship Owner College – Qalandarya Chowk – Sakhi Hassan – Shadman No.1 – Buffer Zone – Fazal Mill – Nipa – NEDUET (Main Campus). -

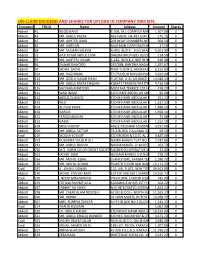

Un-Claim Dividend and Shares for Upload in Company Web Site

UN-CLAIM DIVIDEND AND SHARES FOR UPLOAD IN COMPANY WEB SITE. Company FOLIO Name Address Amount Shares Abbott 41 BILQIS BANO C-306, M.L.COMPLEX MIRZA KHALEEJ1,507.00 BEG ROAD,0 PARSI COLONY KARACHI Abbott 43 MR. ABDUL RAZAK RUFI VIEW, JM-497,FLAT NO-103175.75 JIGGAR MOORADABADI0 ROAD NEAR ALLAMA IQBAL LIBRARY KARACHI-74800 Abbott 47 MR. AKHTER JAMIL 203 INSAF CHAMBERS NEAR PICTURE600.50 HOUSE0 M.A.JINNAH ROAD KARACHI Abbott 62 MR. HAROON RAHEMAN CORPORATION 26 COCHINWALA27.50 0 MARKET KARACHI Abbott 68 MR. SALMAN SALEEM A-450, BLOCK - 3 GULSHAN-E-IQBAL6,503.00 KARACHI.0 Abbott 72 HAJI TAYUB ABDUL LATIF DHEDHI BROTHERS 20/21 GORDHANDAS714.50 MARKET0 KARACHI Abbott 95 MR. AKHTER HUSAIN C-182, BLOCK-C NORTH NAZIMABAD616.00 KARACHI0 Abbott 96 ZAINAB DAWOOD 267/268, BANTWA NAGAR LIAQUATABAD1,397.67 KARACHI-190 267/268, BANTWA NAGAR LIAQUATABAD KARACHI-19 Abbott 97 MOHD. SADIQ FIRST FLOOR 2, MADINA MANZIL6,155.83 RAMTLA ROAD0 ARAMBAG KARACHI Abbott 104 MR. RIAZUDDIN 7/173 DELHI MUSLIM HOUSING4,262.00 SOCIETY SHAHEED-E-MILLAT0 OFF SIRAJUDULLAH ROAD KARACHI. Abbott 126 MR. AZIZUL HASAN KHAN FLAT NO. A-31 ALLIANCE PARADISE14,040.44 APARTMENT0 PHASE-I, II-C/1 NAGAN CHORANGI, NORTH KARACHI KARACHI. Abbott 131 MR. ABDUL RAZAK HASSAN KISMAT TRADERS THATTAI COMPOUND4,716.50 KARACHI-74000.0 Abbott 135 SAYVARA KHATOON MUSTAFA TERRECE 1ST FLOOR BEHIND778.27 TOOSO0 SNACK BAR BAHADURABAD KARACHI. Abbott 141 WASI IMAM C/O HANIF ABDULLAH MOTIWALA95.00 MUSTUFA0 TERRECE IST FLOOR BEHIND UBL BAHUDARABAD BRANCH BAHEDURABAD KARACHI Abbott 142 ABDUL QUDDOS C/O M HANIF ABDULLAH MOTIWALA252.22 MUSTUFA0 TERRECE 1ST FLOOR BEHIND UBL BAHEDURABAD BRANCH BAHDURABAD KARACHI. -

Site Name City a & Y Filling Station Karachi AFTAB SERVICE STATION

Site Name City A & Y Filling Station Karachi AFTAB SERVICE STATION Karachi AHMED FILLING STATION Karachi AHMED FILLING STATION ORANGI Karachi AISHA SERVICE STATION Karachi Al - Ayaan Filling Station Karachi Al Raheem Filling Station Karachi AL-KARIM SERVICE STATION Karachi Almas Filling Station Karachi AL-RAFAY SERVICE STATION Karachi AL-SAEED SERVICE STATION Karachi AL-SIDDIQUE SVC STN Karachi AMMA SERVICE STATION Karachi Arafat Filling Station Karachi ASAD PETROLEUM SERVICE Karachi Atrium Petroleum and CNG Services Karachi AWAN BALOUCH TRUCKING STATION Karachi Babar Filling Station Karachi Beachview Filling Station Karachi Bismillah Associates Karachi Burraq Filling Station Karachi CENTRAL GASOLINE Karachi Central Gasoline II Filling Station Karachi Chairman Service Station Karachi Chinar Filling Station Karachi CNG SYSTEMS Karachi Data Filling Station Karachi Enchante' Filling Station-COCO Karachi ESSA PETROLEUM Karachi Excel Petroleum Service Karachi FAISAL SERVICE STATION Karachi FARZAM FUEL STATION Karachi GOTEWALA SERVICE STATION Karachi GULSHAN SERVICE STATION Karachi HAFIZ SUDAIS FILLING STATION Karachi HIGH SPEED SERVICE STATION Karachi Hub Filling Station Karachi Jannat Filling Station Karachi JAVED SERVICE STATION Karachi Jinnah Petroleum Karachi KAMAL SERVICE STATION Karachi KARIMI AUTOS Karachi KHAWAR SHAHEED SERVICE STATION Karachi Khazan Associates Karachi KHYBER PETROL SERVICE Karachi Lavender Filling Station Karachi LUCKY SERVICE STATION Karachi M/s. Madina Filing Station Karachi Madni Filling Station Karachi MAKKAH AUTOS Karachi Malir Filling Station Karachi Mashallah Associates Karachi MILLAT SERVICE STATION Karachi Mina Filling Station Karachi MM FILLING STATION Karachi Moon Filling Station Karachi NAVEED TRUCKING Karachi New Korangi Filling Station Karachi NEW TOWN FUEL STATION Karachi NORTHERN GASOLINE Karachi QASIM SERVICE STATION Karachi RAJA 2 PETROLEUM Karachi RAJA SERVICE STATION Karachi Reda Filling Station Karachi Rehman Filling Station Karachi REX SERVICE STATION Karachi RM FILLING STATION Karachi S. -

My Memoirs Shah Wali Khan

University of Nebraska at Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Digitized Books Archives & Special Collections 1970 My Memoirs Shah Wali Khan Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/ascdigitizedbooks Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Khan, Shah Wali, "My Memoirs" (1970). Digitized Books. 18. http://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/ascdigitizedbooks/18 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Archives & Special Collections at DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Digitized Books by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MY MEMOIRS ( \ ~ \ BY HIS ROYAL HIGHNESS SARDAR SHAH WALi VICTOR OF KABUL KABUL COLUMN OF JNDEPENDENCE Afghan Coll. 1970 DS 371 sss A313 His Royal Highness Marshal Sardar Shah Wali Khan Victor of Kabul MY MEMOIRS BY HIS ROYAL HIGHNESS MARSHAL SARDAR SHAH WALi VICTOR OF KABUL KABUL 1970 PRINTED IN PAKISTAN BY THE PUNJAB EDUCATIONAL PRESS, , LAHORE CONTENTS PART I THE WAR OF INDEPENDENCE Pages A Short Biography of His Royal Highness Sardar Shah Wali Khan, Victor of Kabul i-iii 1. My Aim 1 2. Towards the South 7 3. The Grand Assembly 13 4. Preliminary Steps 17 5. Fall of Thal 23 6. Beginning of Peace Negotiations 27 7. The Armistice and its Effects 29 ~ 8. Back to Kabul 33 PART II DELIVERANCE OF THE COUNTRY 9. Deliverance of the Country 35 C\'1 10. Beginning of Unrest in the Country 39 er 11. Homewards 43 12. Arrival of Sardar Shah Mahmud Ghazi 53 Cµ 13. Sipah Salar's Activities 59 s:: ::s 14. -

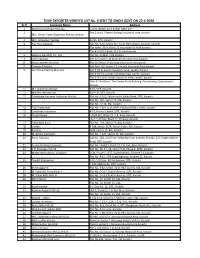

TDAP EXPORTER VERIFIED LIST No. 9 SENT to SINDH GOVT on 22-4-2020 Sr.# Company Name Address 1 Multinational Export Bureau L-10 D, BLOCK 22, F B IND

TDAP EXPORTER VERIFIED LIST No. 9 SENT TO SINDH GOVT ON 22-4-2020 Sr.# Company Name Address 1 Multinational Export Bureau L-10 D, BLOCK 22, F B IND. AREA KHI 2 Plot 2 and 17 Sector Korangi Industrial Area, Karachi M/s. United Towel Exporters Private Limited 3 M/s. Homecare Textiles D-115, SITE, Karachi 4 Five Star Apparels Plot No. E-92, Sector No. 31-D, P&T Society, Korangi, Karachi. Plot No# L-33/A, Block 22 Industrial F.B Area Karachi Plot # LA 8/19 Block 22 F.B Area Karachi 5 Lakhany Silk Mills Pvt. Ltd. Plot No. D/48-D, SITE Karachi 7 Vista Apparels Plot 6/1, Sector 15 Korangi Industrial Area Karachi 8 Nova Leathers (Pvt) Ltd Plot 30 Sector 15 Korangi Industrial Area Karachi 9 Threads & Motifs Plot No# 126, Sector 15, Korangi Industrial Area Karachi 10 Gul Ahmed Textile Mills Ltd Plot # HT-8, Landhi Industrial Area, Landhi, Karachi Plot # HT-19, Landhi Industrial Area, Landhi, Karachi Plot # H-5, H-6, Landhi Industrial Area, Landhi, Karachi 16th & 23rd Floor, The Center Point Building, Expressway, Qayyumabad, Karachi 11 M.I. Industries (Dying) B-45, SITE, Karachi. 12 Mahee International F/413-B, SITE, Karachi. 13 Cambridge Garment Industries Pvt Ltd. Plot No. A-5/1, Fakharuddin Valika Road, SITE, Karachi. Plot No. 102, Sector 27, KIA, Karachi. Plot No. C-124, KIA, Karachi. 14 ZIQI Enterprises Plot No. 2 & 9, A-VI, KEPZ, PO Box18700, Landhi, Karachi. 15 Combined Industries A-15, Binoria Chowk, SITE, Karachi. 16 Globe Dyeing L-26/B & C, Block 22, F.B. -

Branch Directory

Dubai Islamic Bank - Branch Directory Abbottabad S.No Branch Code Branch Name Address Province PABX Number Khyber 1 31 Abbottabad CB 306/4, Lala Rukh Plaza, Mansehra Road, Abbottabad, Pakhtunkhwa 0992-342239-41 Ground Floor, Shop Nos.12 & 13, Mamu Jee Market, Opp GPO, Cantt Khyber 2 161 Abbottabad 2 Bazaar, Abbottabad, Pakhtunkhwa 0992-342394 Attock S.No Branch Code Branch Name Address Province PABX Number Plot No B-1-63, A Block, Khan Plaza, Fawara Chowk, Civil Bazaar, Attock. 3 73 Attock Punjab. Punjab 057-2702054-6 Mehria Town Housing Scheme, Phase 1, Shop No. 25 + 39, Block - A, Kamra 4 187 Mehria Road - Attock Punjab Bahawalpur S.No Branch Code Branch Name Address Province PABX Number Model Town Plot No 12.B, Khewat No 148,Khatooni No.246,General Officer Colony, 062-2889951-3, 5 71 Bahawalpur Model Town B, Bahawalpur,Punjab. Punjab 2889961-3 Burewala S.No Branch Code Branch Name Address Province PABX Number 439/EB, Block C, Al-Aziz Super Market, College Road, Burewala. Vehari 6 95 Burewala District, Punjab. Punjab 067-3772388 Chakwal S.No Branch Code Branch Name Address Province PABX Number Ground Floor, No. 1636, Khewat 323, Opposite Main PTCL Office Main 7 172 Chakwal Talagang Road, Chakwal District, Punjab. Punjab 054-3544115 Chaman S.No Branch Code Branch Name Address Province PABX Number Ground Floor, Haji Ayub Plaza, Plot No. Mall Road, Chaman.Killa Abdullah 8 122 Chaman District, Balochistan . Balochistan 0826-61806-61812 Dadyal S.No Branch Code Branch Name Address Province PABX Number Ground Floor, Khasra No. 552, Moza Mandi, Kacheri Road, Dadyal, District Azad Jammu & 9 120 Dadyal Mirpur Azad Jammu Kashmir.