The Red Locked Room

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Japanese Women's Science Fiction: Posthuman Bodies and the Representation of Gender Kazue Harada Washington University in St

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations Arts & Sciences Spring 5-15-2015 Japanese Women's Science Fiction: Posthuman Bodies and the Representation of Gender Kazue Harada Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds Part of the East Asian Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Harada, Kazue, "Japanese Women's Science Fiction: Posthuman Bodies and the Representation of Gender" (2015). Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 442. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds/442 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Arts & Sciences at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS Department of East Asian Languages & Cultures Dissertation Examination Committee: Rebecca Copeland, Chair Nancy Berg Ji-Eun Lee Diane Wei Lewis Marvin Marcus Laura Miller Jamie Newhard Japanese Women’s Science Fiction: Posthuman Bodies and the Representation of Gender by Kazue Harada A dissertation presented to the Graduate School of Arts & Sciences of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2015 St. Louis, Missouri © 2015, Kazue Harada -

Portrayals of Police and Crime in Japanese Anime and Manga

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Carolina Digital Repository ALL THE EVIL OF GOOD: PORTRAYALS OF POLICE AND CRIME IN JAPANESE ANIME AND MANGA By Katelyn Mitchell Honors Thesis Department of Asian Studies University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill April 23, 2015 Approved: INGER BRODEY (Student’s Advisor) 1 “All the Evil of Good”: Portrayals of Police and Crime in Japanese Anime and Manga By Katelyn Mitchell “Probity, sincerity, candor, conviction, the idea of duty, are things that, when in error, can turn hideous, but – even though hideous, remain great; their majesty, peculiar to the human conscience, persists in horror…Nothing could be more poignant and terrible than [Javert’s] face, which revealed what might be called all the evil of good” -Victor Hugo, Les Misérables Volume I, Book VIII, Chapter III: “Javert Satisfied” Abstract This thesis examines and categorizes the distinct, primarily negative, portrayals of law enforcement in Japanese literature and media, beginning with its roots in kabuki drama, courtroom narratives and samurai codes and tracing it through modern anime and manga. Portrayals of police characters are divided into three distinct categories: incompetents used as a source of comedy; bland and consistently unsuccessful nemeses to charismatic criminals, used to encourage the audience to support and favor these criminals; or cold antagonists fanatically devoted to their personal definition of ‘justice’, who cause audiences to question the system that created them. This paper also examines Western influences, such as Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes and Victor Hugo’s Inspector Javert, on these modern media portrayals. -

AKIYOSHI SUSUKI/ Cross-Cultural Reading of Doll-Love Novels In

CROSS-CULTURAL READING OF DOLL-LOVE NOVELS IN JAPAN AND THE WEST Akiyoshi Suzuki Abstract: This paper makes the following two points: first, Japanese doll-love novels, especially those at the dawn of the genre in Japan, such as Jun’ichiro Tanizaki’s Some Prefer Nettles (Tade kuu mushi), should be read from the perspective of Japanese reality, history, philosophy, and culture. Second, the popular criticism of doll-love novels needs to be reconsidered as representing adult male childishness and female objectification. 1 Introduction It has been said that love of a doll or a figure represents narcissism, fetishism, or a transitional object. These are technical terms of psychoanalysis, and supposedly, psychoanalytical theory is universally applicable to human beings. The representation of love of a doll in a literary text and thus the text itself are, therefore, universally regarded as psychically strange. Reading a literary text from a feminist perspective leads to the same conclusion. In feminist theory, doll-love, especially a novel of an adult male love of a female doll, is regarded as asymmetrical in gender difference and thus outrageous and condemnable. Feminist criticism of the objectification of a woman in love, as Atsushi Koyano points out, is based on an asymmetric relation in mutual love, but not in one-sided love (Koyano, 2001, 24). A doll-love novel is one- sided love as long as the doll is regarded as an object; generally, a doll has no will, no heart, and no language. In many novels, however, an adult male protagonist loves a doll as a female human or a female human as a doll in order to gratify his own desire, and thus his objectification of a woman can be criticized because he does not see the woman as a living individual. -

Portrayals of Police and Crime in Japanese Anime and Manga

ALL THE EVIL OF GOOD: PORTRAYALS OF POLICE AND CRIME IN JAPANESE ANIME AND MANGA By Katelyn Mitchell Honors Thesis Department of Asian Studies University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill April 23, 2015 Approved: INGER BRODEY (Student’s Advisor) 1 “All the Evil of Good”: Portrayals of Police and Crime in Japanese Anime and Manga By Katelyn Mitchell “Probity, sincerity, candor, conviction, the idea of duty, are things that, when in error, can turn hideous, but – even though hideous, remain great; their majesty, peculiar to the human conscience, persists in horror…Nothing could be more poignant and terrible than [Javert’s] face, which revealed what might be called all the evil of good” -Victor Hugo, Les Misérables Volume I, Book VIII, Chapter III: “Javert Satisfied” Abstract This thesis examines and categorizes the distinct, primarily negative, portrayals of law enforcement in Japanese literature and media, beginning with its roots in kabuki drama, courtroom narratives and samurai codes and tracing it through modern anime and manga. Portrayals of police characters are divided into three distinct categories: incompetents used as a source of comedy; bland and consistently unsuccessful nemeses to charismatic criminals, used to encourage the audience to support and favor these criminals; or cold antagonists fanatically devoted to their personal definition of ‘justice’, who cause audiences to question the system that created them. This paper also examines Western influences, such as Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes and Victor Hugo’s Inspector Javert, on these modern media portrayals. It also examines the contradictions between these negative, antagonistic characters and existing facts and statistics – Japan’s low crime rate and generally high reports of civilian satisfaction with the police. -

Copyright by Benjamin Paul Miller 2012

Copyright by Benjamin Paul Miller 2012 The Thesis Committee for Benjamin Paul Miller Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Drawn in Bloodlines: Blood, Pollution, Identity, and Vampires in Japanese Society APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: Kirsten C. Fischer Patricia Maclachlan Drawn in Bloodlines: Blood, Pollution, Identity, and Vampires in Japanese Society by Benjamin Paul Miller, B.A. Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2012 Dedication I dedicate this thesis to Yule Brynner, who put it most aptly when he said, “So let it be written, so let it be done.” Acknowledgements I would like to acknowledge my graduate advisor, Dr. Kirsten C. Fischer, for her support and guidance in writing this thesis. I would also like to express my gratitude to my parents, Sherman and Victoria, for their unwavering support of my academic career. v Abstract Drawn in Bloodlines: Blood, Pollution, Identity, and Vampires in Japanese Society Benjamin Paul Miller, M.A. The University of Texas at Austin, 2007 Supervisor: Kirsten C. Fischer This thesis is an examination of the evolution of blood ideology, which is to say the use of blood as an organizing metaphor, in Japanese society. I begin with the development of blood as a substance of significant in the eighth century and trace its development into a metaphor for lineage in the Tokugawa period. I discuss in detail blood’s conceptual and rhetorical utility throughout the post-Restoration period, first examining its role in establishing a national subjectivity in reference to both the native intellectual tradition of the National Learning and the foreign hegemony of race. -

170313 Library Books List.Pdf

NDC no. of shelf Title Author 104 83 Toshihiko Izutsu and the Philosophy of WORD : In Search of the Spiritual Orient Eisuke Wakamatsu LTCB International Library Selection No.37 HOLY FOOLERY IN LIFE OF JAPAN 210 51 A HISTORICAL OVERVIEW HIGUCHI KAZUNORI JAPANESE JOURNAL OF EUROPEAN STUDIES 90 302 2014 vol.2 Organization for European Studies, Waseda University Research and Training Institute 90 Ministry of Justice 302 WHITE PAPER ON CRIME 2013 Japan Rethinking "Japanese Studies" from Practices in the Nordic Region Liu Jianhui ; Sano Mayuko 97 304 「日本研究」再考-北欧の実践から 劉建輝;佐野真由子 305 76 日本研究 第45集 伊東貴之 The Union of National Economic Associations in Japan 96 305 Information Bulletin of The Union of National Economic Association in Japan No.33 日本経済学会連合 LTCB International Library Selection No.36 JAPAN'S ASIAN DIPLOMACY 319 51 A Legacy of Two Millennia OGURA KAZUO 319 90 外交青書 2014 平成26年版(第57号) 外務省 319 96 外交 Vol.15 Sept. 2012 「外交」編集委員会 319 96 Diplomatic Bluebook 2012 Summary Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan 319 96 外交青書 2012 平成24年版(第55号) 外務省 319 96 国際交流基金 日本語教育紀要 第9号 2014 独立行政法人国際交流基金 日本語国際センター 事業化開発チーム 319 97 外交史料館報 第27号 平成25年12月 外務省外交史料館 JAPAN & BELGIUM W.F. Vande Walle 97 319 An Itinerary of Mutual Inspiration David De Cooman 319 reception Megumi Shigeru and Sakie Yokota 150 Years of Friendship between Japan and Belgium 1866-2016 reception 319 (NB: 2 examples) 150 Years of Friendship between Japan and Belgium Celebration Committee THE RISE OF SHARING 83 332 FOURTH-STAGE CONSUMER SOCIETY IN JAPAN Miura Atsushi The Power of the Weave 90 332 The Hidden -

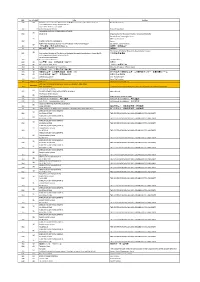

Ⅱ公衆への観覧 1 上映会等 Screening Programs and Exhibitions

Ⅱ公衆への観覧 1 上映会等 Screening Programs and Exhibitions 1-1 入場者数 Number of Visitors プログ 上 映 1回平均 上映日数 ラム数 作品数 上映回数 入場者数 入館者数 上映会(大ホール) 205日 224 288 449 160人 71,380人 上映会(小ホール) 27日 27 37 54 88人 4,747人 上映会計 232日 251 325 503 151人 76,127人 キャンパス 一般 シニア 学生 小人 障害者等 無料 メンバーズ 上映会 46.52% 29.47% 1.52% 0.06% 10.46% 5.17% 6.41% 入館者数内訳 開催日数 1日平均入館者数 入館者数 展覧会(展示室) 213日 70人 14,988人 上映会と展覧会計 445日 91,115人 1-1-1 上映会 Screening Programs 回数 上映会名 入場者数(人) 会場 379 生誕100年 木下忠司の映画音楽 18,352人 大ホール 380 《京橋映画小劇場No.33》アンコール特集:2015年度上映作品より 2,088人 小ホール 381 EUフィルムデーズ2016 11,458人 大ホール 382 生誕100年 映画監督 加藤泰 17,684人 大ホール 383 《京橋映画小劇場No.34》 ドキュメンタリー作家 羽田澄子 2,659人 小ホール 384 第38回PFF 4,533人 大ホール および小ホール 385 シネマの冒険 闇と音楽2016 スウェーデン映画協会コレクション 1,416人 大ホール 386 UCLA映画テレビアーカイブ 復元映画コレクション 4,458人 大ホール 387 NFC所蔵外国映画選集2016 3,264人 大ホール 388 DEFA70周年 知られざる東ドイツ映画 6,210人 大ホール 389 自選シリーズ 現代日本の映画監督5 押井守 4,005人 大ホール 129 1-1-2 展覧会 Visitors to Exhibitions 回数 展覧会名 入場者数(人) 47 写真展 映画館 映画技師/写真家 中馬聰の仕事 4,747人 48 角川映画の40年 5,822人 49 戦後ドイツの映画ポスター 4,419人 130 1-2 上映会 Screening Programs 上映会一覧(開館より平成27年度まで) 1-2-1 Screenings from the Opening Programs in Fiscal 1970 until 2015 回数 企画名 1 アメリカ古典映画の回顧 昭和 年度[1970] 45 Retrospective of American Classic Films 2 成瀬巳喜男監督の特集 Films of Mikio Naruse 3 シナリオライター野田高梧をしのぶ In Memory of the Scriptwriter Kogo Noda 4 フランス映画の歴史 History of French Films 5 ドイツ映画の回顧 Retrospective of German Films 6 田中絹代特集―一女優の歩みに見る日本映画史 昭和 年度[1971] 46 Kinuyo Tanaka-Japanese Film History as Seen by an Actress 7 内田吐夢監督の回顧上映 Retrospective of Tomu Uchida 8 フランス映画の特集 French Film Program 9 アニメーション映画の回顧 Retrospective of Animation -

Note on the English Guidebook for Your Information, We Have Provided

Note on the English Guidebook For your information, we have provided in the following section an English translation of the Application Guidebook of the Graduate School of Humanities, Seikei University, for 2020 enrollment. Note that this is neither the official or current issue of the Guidebook, which is a PDF file you can obtain from the following page: https://www.seikei.ac.jp/university/s-net/admissions/graduate_school.html When you apply, please refer primarily to the official Japanese Guidebook. Since the English translation is based on the previous years’ Guidebook, none of the subsequent changes have been incorporated. In all cases, the terms and conditions in the official Japanese Guidebook apply, rather than those in the English translation. While some of the classes in the Graduate School of Humanities at Seikei University are conducted in English, Japanese proficiency is necessary for enrollment, as well as life here after that. GRADUATE SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES: THE THREE POLICIES For Freshers 2020 I. Founding Spirits and Educational Goals Based on the educational philosophy that “a truly human education aims to cultivate a spontaneous spirit and the discovery and development of individuality” advanced by the founder of Seikei University, Nakamura Haruji, three aims have been put forward: 1. Instead of attaching too much importance to intellectual education, practice a human education that has a balance of personality, knowledge, mind and body, to produce human resources that combine solid education and rich humanity and can dedicate themselves to the development of the society. 2. We teach and research on theories and applications of the academics, aim at the creation of free knowledge, and master its depth to contribute to the progress of culture. -

Cross-Cultural Reading of Doll0love Novels in Japan and the West

CROSS-CULTURAL READING OF DOLL-LOVE NOVELS IN JAPAN AND THE WEST ∗ Akiyoshi Suzuki Abstract: This paper makes the following two points: first, Japanese doll-love novels, especially those at the dawn of the genre in Japan, such as Jun’ichiro Tanizaki’s Some Prefer Nettles (Tade kuu mushi), should be read from the perspective of Japanese reality, history, philosophy, and culture. Second, the popular criticism of doll-love novels needs to be reconsidered as representing adult 1 male childishness and female objectification. Introduction It has been said that love of a doll or a figure represents narcissism, fetishism, or a transitional object. These are technical terms of psychoanalysis, and supposedly, psychoanalytical theory is universally applicable to human beings. The representation of love of a doll in a literary text and thus the text itself are, therefore, universally regarded as psychically strange. Reading a literary text from a feminist perspective leads to the same conclusion. In feminist theory, doll-love, especially a novel of an adult male love of a female doll, is regarded as asymmetrical in gender difference and thus outrageous and condemnable. Feminist criticism of the objectification of a woman in love, as Atsushi Koyano points out, is based on an asymmetric relation in mutual love, but not in one-sided love (Koyano, 2001, 24). A doll-love novel is one- sided love as long as the doll is regarded as an object; generally, a doll has no will, no heart, and no language. In many novels, however, an adult male protagonist loves a doll as a female human or a female human as a doll in order to gratify his own desire, and thus his objectification of a woman can be criticized because he does not see the woman as a living individual. -

Nei Racconti C'è Veleno Identità E Immagini Femminili in Quattro Racconti Di Kirino Natsuo

Corso di Laurea magistrale in Lingue e culture dell'Asia Orientale Tesi di Laurea Nei racconti c'è veleno Identità e immagini femminili in quattro racconti di Kirino Natsuo Relatore Ch. Prof. Paola Scrolavezza Correlatore Ch. Prof. Luisa Bienati Laureando Lucia Durì Matricola 813831 Anno Accademico 2011 / 2012 要旨 1951 年に金沢に生まれた桐野夏生は、現代の日本文学界の中で非常に興味深い存在 である。世界的にも有名になった理由は彼女の作品の独創性と面白さだけではないと 思う。桐野の作品が世界中の読者を魅了できたのは、それに含まれる現代社会の問題 が日本のだけのものではなく、世界各国の問題でもあると認められるからである。 そこで、本論文の第一章では、桐野夏生の著作について論じながら、作品の特色や 主な主題を示します。 桐野夏生が有名になり始めたのは 1993 年に『顔に降りかかる雨』という推理小説が 江戸川乱歩賞を受賞してからのことである。日本では、1960 年ごろまでは女性はこの ジャンルの発達においてあまり重要な役割を果たさなかったが、1980 年ごろから女性 作家による、社会批判を含んだ推理小説の本格的なブームが起きた。推理小説で初登 場する桐野も、男性の領分であったこのジャンルにおいて、構造、ルール、また主題 の点からも、挑戦を試みた女性作家の一人として認められる。女性探偵の村野ミロの 一連の成功と失敗を語ることにより、桐野はこのジャンルにおける女性の登場人物の 役割を回復するだけではなく、いまだに男性的な見方に基づいた家父長制社会におけ る女性の諸問題をはっきり示すこともできたと思う。 日本推理作家協会賞を受賞 した『アウト』は 2004 年エドガー賞にノミネートされ、 日本人作家が同賞にノミネートされた初の小説となった。その結果、『グロテスク』 や『リアルワールド』が英語に翻訳されたこともあり、桐野夏生は世界的な名声を得 た。 『アウト』と『グロテスク』の成功で桐野はハードボイルド小説家あるいは犯罪小 説家と呼ばれもする一方、彼女の作品のテーマはさまざまなジャンルに跨り、「桐野 ジャンル」というひとつの別のジャンルであると評されたこともある。ジャンルに注 意を集中するよりも、桐野の小説は社会から疎外されている個人あるいは集団の不自 由さや不安さ、または女性の近代の社会的な役割などのテーマを扱う。「毒」という 人間の乱暴で、利己的で暗い面を表すのが小説の目的ではなく、さまざまな人物の抑 制された希望が発生させるエネルギーの表れを描こうとしているのであろう。 I 本論文の第二章ではまた、四つの短編小説を翻訳と検討するが、これらは、桐野の 初期の作品の推理小説から離れる一方、彼女の全作品との多くの共通点があると言え る。詳しく言えば、さまざまな女性についての物語であり、作家が『アウト』や『グ ロテスク』でも検討した女性の社会的なイメージと人格との関連を表す。 『使ってしまったコインについて』は三人の女子の同性愛めいた友情の決裂につい ての話であり、「女のステレオタイプ化」に影響された女性の、男性に対しての無抵 抗な態度が見られる。ある土曜日の夜、三人の主人公の女子は「先生」と呼ばれてい る女に SM ショーに誘われる。美人のミクは未知の人にそのディシプリンショーに突然 -

Investigating the Revival of the Boy Detective in Japan's Lost Decade

Manga, Murder and Mystery: Investigating the Revival of the Boy Detective in Japan’s Lost Decade by Tsugumi Okabe A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Comparative Literature University of Alberta © Tsugumi Okabe, 2019 Abstract The past two decades have seen a sustained growth in the number of Japanese mystery and detective comics (manga) publications that feature boys (and girls) as crime fighting agents. While the earliest incarnation of the boy detective character type can be traced to the works of Edogawa Rampo (1894-1965), little critical attention has been paid to the impact of his works on contemporary manga narratives. This thesis takes up the genre of Japanese mystery/detective manga and explores the construction of the boy detective (shōnen tantei) to address the crisis of young adult culture during the so-called Lost Decade in Japan. It conducts a comparative textual analysis of three commercially successful manga: Kanari Yōzaburō and Seimaru Amagi’s Kindaichi Shōnen no Jikenbo (1992-1997), Aoyama Gōshō’s Meitantei Konan (1994- ), and Ohba Tsugumi’s Death Note (2003-06), and reveals that the boy detective is defined by his role as the other, but that each series deals with this otherness in thematically different ways in response to the discursive formation of youth delinquents in 1990s Japan. Additionally, because the boy detective tradition in manga emerged from more traditional literature, this thesis takes an interdisciplinary approach to contextualizing the deeply complex literary history of Japanese detective fiction as it contributes to an understanding of how (youth) identity can be analyzed in detective manga.