Domestic Intelligence: New Powers, New Risks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Drowning in Data 15 3

BRENNAN CENTER FOR JUSTICE WHAT THE GOVERNMENT DOES WITH AMERICANS’ DATA Rachel Levinson-Waldman Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law about the brennan center for justice The Brennan Center for Justice at NYU School of Law is a nonpartisan law and policy institute that seeks to improve our systems of democracy and justice. We work to hold our political institutions and laws accountable to the twin American ideals of democracy and equal justice for all. The Center’s work ranges from voting rights to campaign finance reform, from racial justice in criminal law to Constitutional protection in the fight against terrorism. A singular institution — part think tank, part public interest law firm, part advocacy group, part communications hub — the Brennan Center seeks meaningful, measurable change in the systems by which our nation is governed. about the brennan center’s liberty and national security program The Brennan Center’s Liberty and National Security Program works to advance effective national security policies that respect Constitutional values and the rule of law, using innovative policy recommendations, litigation, and public advocacy. The program focuses on government transparency and accountability; domestic counterterrorism policies and their effects on privacy and First Amendment freedoms; detainee policy, including the detention, interrogation, and trial of terrorist suspects; and the need to safeguard our system of checks and balances. about the author Rachel Levinson-Waldman serves as Counsel to the Brennan Center’s Liberty and National Security Program, which seeks to advance effective national security policies that respect constitutional values and the rule of law. -

Who Is the Attorney General's Client?

\\jciprod01\productn\N\NDL\87-3\NDL305.txt unknown Seq: 1 20-APR-12 11:03 WHO IS THE ATTORNEY GENERAL’S CLIENT? William R. Dailey, CSC* Two consecutive presidential administrations have been beset with controversies surrounding decision making in the Department of Justice, frequently arising from issues relating to the war on terrorism, but generally giving rise to accusations that the work of the Department is being unduly politicized. Much recent academic commentary has been devoted to analyzing and, typically, defending various more or less robust versions of “independence” in the Department generally and in the Attorney General in particular. This Article builds from the Supreme Court’s recent decision in Free Enterprise Fund v. Public Co. Accounting Oversight Board, in which the Court set forth key principles relating to the role of the President in seeing to it that the laws are faithfully executed. This Article draws upon these principles to construct a model for understanding the Attorney General’s role. Focusing on the question, “Who is the Attorney General’s client?”, the Article presumes that in the most important sense the American people are the Attorney General’s client. The Article argues, however, that that client relationship is necessarily a mediated one, with the most important mediat- ing force being the elected head of the executive branch, the President. The argument invokes historical considerations, epistemic concerns, and constitutional structure. Against a trend in recent commentary defending a robustly independent model of execu- tive branch lawyering rooted in the putative ability and obligation of executive branch lawyers to alight upon a “best view” of the law thought to have binding force even over plausible alternatives, the Article defends as legitimate and necessary a greater degree of presidential direction in the setting of legal policy. -

Honesty Won't Aid Enemies; CIA INTERROGATION TACTICS

Honesty won’t aid enemies; CIA INTERROGATION TACTICS The National Law Journal (Online) November 26, 2007 Monday Copyright 2007 ALM Media Properties, LLC All Rights Reserved Further duplication without permission is prohibited Length: 949 words Byline: Andrew Kent / Special to The National Law Journal, Special to the national law journal Body The Bush administration maintains that it cannot publicly discuss or even name the harsh interrogation techniques used by the CIA to break the silence of ″high value″ al-Queda captives like Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, who devised the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks. Recently, Michael Mukasey’s nomination to be attorney general ran into trouble when he declined senators’ requests for his opinion on the legality of waterboarding ? forced inhalation of water, causing choking and asphyxiation ? a technique reportedly used by the CIA on Mohammed and a few others. Mukasey was confirmed, but controversy about the CIA’s methods of interrogating al-Queda leadership, and the official secrecy about them, continues. The Bush administration and its supporters typically offer two reasons why the CIA’s interrogation methods must be secret. Neither is convincing. The principal justification is a variation on the tune the administration has played for years ? opposing us means aiding the enemy. The other justification is protecting CIA interrogators from potential liability. President Bush has repeated that the administration cannot discuss specific methods because ″it doesn’t make any sense to broadcast to the enemy what they ought to prepare for and not prepare for.″ As another official put it, the government cannot ″publicize to the enemy what practices may be on the table and what practices may be off the table. -

Office of the Attorney General the Honorable Mitch Mcconnell

February 3, 2010 The Honorable Mitch McConnell United States Senate Washington, D.C. 20510 Dear Senator McConnell: I am writing in reply to your letter of January 26, 2010, inquiring about the decision to charge Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab with federal crimes in connection with the attempted bombing of Northwest Airlines Flight 253 near Detroit on December 25, 2009, rather than detaining him under the law of war. An identical response is being sent to the other Senators who joined in your letter. The decision to charge Mr. Abdulmutallab in federal court, and the methods used to interrogate him, are fully consistent with the long-established and publicly known policies and practices of the Department of Justice, the FBI, and the United States Government as a whole, as implemented for many years by Administrations of both parties. Those policies and practices, which were not criticized when employed by previous Administrations, have been and remain extremely effective in protecting national security. They are among the many powerful weapons this country can and should use to win the war against al-Qaeda. I am confident that, as a result of the hard work of the FBI and our career federal prosecutors, we will be able to successfully prosecute Mr. Abdulmutallab under the federal criminal law. I am equally confident that the decision to address Mr. Abdulmutallab's actions through our criminal justice system has not, and will not, compromise our ability to obtain information needed to detect and prevent future attacks. There are many examples of successful terrorism investigations and prosecutions, both before and after September 11, 2001, in which both of these important objectives have been achieved -- all in a manner consistent with our law and our national security interests. -

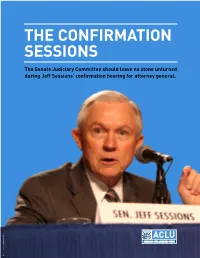

The Confirmation Sessions

THE CONFIRMATION SESSIONS The Senate Judiciary Committee should leave no stone unturned during Jeff Sessions’ confirmation hearing for attorney general. Photo: . Gage Skidmore/Flickr Photo: CONTENTS 3 INTRODUCTION 4 WOULD JEFF SESSIONS CONTINUE THE PUSH FOR POLICE REFORM? 7 WOULD JEFF SESSIONS PROTECT VOTING RIGHTS? WOULD JEFF SESSIONS PROVIDE DUE PROCESS TO IMMIGRANTS 9 AS WELL AS PREVENT THE STATES FROM ENFORCING FEDERAL IMMIGRATION LAW? WOULD JEFF SESSIONS WORK TO REFORM THE POLICIES OF MASS 11 INCARCERATION? WOULD JEFF SESSIONS RESPECT RELIGIOUS LIBERTY, ENSURE 13 THAT RELIGIOUS DISCRIMINATION DOES NOT INFECT U.S. LAWS, AND PROTECT AMERICAN MUSLIMS FROM RELIGIOUS DISCRIMINATION? WOULD JEFF SESSIONS CONTINUE THE JUSTICE DEPARTMENT’S FIGHT 15 FOR LGBT EQUALITY? WOULD JEFF SESSIONS PROTECT VICTIMS OF DOMESTIC VIOLENCE 16 AND SEXUAL ASSAULT? WOULD JEFF SESSIONS PROTECT U.S. CITIZENS FROM MASS 17 SURVEILLANCE AND FIGHT TO KEEP THEIR SENSITIVE DATA SAFE? 18 WOULD SESSIONS FOLLOW THE LAW ON TORTURE? WOULD JEFF SESSIONS ENFORCE FEDERAL LAW TO PROTECT 19 ABORTION CLINICS? 20 CONCLUSION 21 ENDNOTES 2 THE CONFIRMATION SESSIONS ore than thirty years ago, Jefferson Beauregard Sessions III, President-elect Donald Trump’s pick M for Attorney General, was in a similar situation as he will be on January 10 when he goes before the Senate Judiciary Committee for his confirmation hearing. Tapped by President Ronald Reagan for a federal judgeship in 1986, Sessions sat before the very same committee for his previous confirmation hearing. Things did not go well. Witnesses accused Sessions, then the U.S. attorney for the southern district of Alabama, of repeat- edly making racially insensitive and racist remarks. -

Aspiring to a Model of the Engaged Judge

Maurice A. Deane School of Law at Hofstra University Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law Hofstra Law Faculty Scholarship 2019 Aspiring To A Model of the Engaged Judge Ellen Yaroshefsky Maurice A. Deane School of Law at Hofstra University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Ellen Yaroshefsky, Aspiring To A Model of the Engaged Judge, 74 N.Y.U. Ann. Surv. Am. L. 393 (2019) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/faculty_scholarship/1251 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hofstra Law Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ASPIRING TO A MODEL OF THE ENGAGED JUDGE ELLEN YAROSHEFSKY* In 1967, within months of his appointment by President Lyn- don Johnson to the Federal Bench in Detroit, Judge Damon Keith, [a] rookie judge and an African American . faced contro- versy almost immediately when, in an unusual confluence of circumstance, four divisive cases landed on his docket-all of which concerned hidden discriminatory practices that were deeply woven into housing, education, employment, and po- lice institutions. Keith shook the nation as he challenged the status quo and faced off against angry crowds, the KKK, corpo- rate America, and even a sitting U.S. President.' In 1970, Judge Keith ordered citywide busing in Pontiac, Mich- igan, to help integrate the city's schools-a ruling that prompted death threats against him and intense resistance by some white par- ents. -

Jamie S. Gorelick

Jamie S. Gorelick May 30, 2006; May 29, 2007; May 16, 2014 through July 27, 2016 Recommended Transcript of Interview with Jamie S. Gorelick (May 30, 2006; May 29, Citation 2007; May 16, 2014 through July 27, 2016), https://abawtp.law.stanford.edu/exhibits/show/jamie-s-gorelick. Attribution The American Bar Association is the copyright owner or licensee for this collection. Citations, quotations, and use of materials in this collection made under fair use must acknowledge their source as the American Bar Association. Terms of Use This oral history is part of the American Bar Association Women Trailblazers in the Law Project, a project initiated by the ABA Commission on Women in the Profession and sponsored by the ABA Senior Lawyers Division. This is a collaborative research project between the American Bar Association and the American Bar Foundation. Reprinted with permission from the American Bar Association. All rights reserved. Contact Please contact the Robert Crown Law Library at Information [email protected] with questions about the ABA Women Trailblazers Project. Questions regarding copyright use and permissions should be directed to the American Bar Association Office of General Counsel, 321 N Clark St., Chicago, IL 60654-7598; 312-988-5214. ABA Senior Lawyers Division Women Trailblazers in the Law ORAL HISTORY of JAMIE GORELICK Interviewer: Pamela A. Bresnahan Dates of Interviews: May 30, 2006 May 29, 2007 The following is the transcript of an interview with Jamie Gorelick conducted on May 30, 2006 and May 29, 2007, for the Women Trailblazers in the Law, a project of the American Bar Association Commission on Women in the Profession. -

Preserve the Constitution Series

PRESERVE the A SERIES FROM THE HERItaGE FOUNDatION The Constitution of the United States of America has Featuring the Attorneys General of Presidents endured over two centuries. Yet modern liberalism and Reagan and Bush activist judges have rejected America’s core principles, denigrating some constitutional rights with which they disagree, and making up others. The future of liberty depends on America reclaiming its constitutional first principles. Meese The Heritage Foundation’s Preserve the Constitution Series seeks to change America’s course by restoring the courts to their constitutional role—to protect individual liberty, property rights, and free enterprise—and to enforce the constitutional limits on government. Ashcroft Informing citizens on topics related to the Constitution and rule of law, this ongoing series will feature lectures, panel discussions, and other events with some of the nation’s most respected judges, legal scholars, lawyers, and policy analysts. Mukasey For more information on the Preserve the Constitution Series, visit heritage.org/RuleOfLaw Calendar of Events All events will be webcast live from The Heritage Foundation in Washington, D.C. SEPTEMBER Click the Event Title below to RSVP and learn more about each event. SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT September 9, 2011, 12:00 p.m. 1 2 3 A Constitutional President: Ronald Reagan and The Founding Featuring Steve Hayward, Author of The Age of Reagan and Jim Miller, 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 former Reagan Cabinet Member Hosted by Edwin Meese, former United States Attorney General 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 September 13, 2011, 12:00 p.m. -

Obscure but Powerful: Shaping U.S. Immigration Policy Through Attorney General Referral and Review

RETHINKING U.S. IMMIGRATION POLICY INITIATIVE Obscure but Powerful Shaping U.S. Immigration Policy through Attorney General Referral and Review By Sarah Pierce U.S. IMMIGRATION POLICY PROGRAM Obscure but Powerful Shaping U.S. Immigration Policy through Attorney General Referral and Review By Sarah Pierce Migration Policy Institute January 2021 Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... 1 1 Introduction .............................................................................................................................................. 2 2 History of the Attorney General’s Referral and Review Power ........................ 3 A. The Homeland Security Act and Its Effects .................................................................................................6 B. Referral and Review as an Administrative Tool .........................................................................................9 3 The Trump Administration’s Use of Self-Referral ...................................................... 12 A. Restricting Access to Asylum ............................................................................................................................13 B. Eliminating Immigration Judge Discretion ..............................................................................................17 4 The Future of Self-Referral ......................................................................................................... -

Political Control of Federal Prosecutions: Looking Back and Looking Forward

Columbia Law School Scholarship Archive Faculty Scholarship Faculty Publications 2009 Political Control of Federal Prosecutions: Looking Back and Looking Forward Daniel C. Richman Columbia Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Administrative Law Commons, Law and Politics Commons, and the President/Executive Department Commons Recommended Citation Daniel C. Richman, Political Control of Federal Prosecutions: Looking Back and Looking Forward, 58 DUKE L. J. 2087 (2009). Available at: https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship/2464 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at Scholarship Archive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Scholarship Archive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. POLITICAL CONTROL OF FEDERAL PROSECUTIONS: LOOKING BACK AND LOOKING FORWARD DANIEL RICHMANt ABSTRACT This Essay explores the mechanisms of control over federal criminal enforcement that the administration and Congress used or failed to use during George W. Bush's presidency. It gives particular attention to Congress, not because legislators played a dominant role, but because they generally chose to play such a subordinate role. My fear is that the media focus on management inadequacies or abuses within the Justice Department during the Bush administrationmight lead policymakers and observers to overlook the -

Senior Leadership Electronic Records from Administration of Janet Reno (1993-2001 ), John Ashcroft (2001-2005), Alberto Gonzales

NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION Request for Records DlsposlUon Aulhority Records Schedule: DAA-0080-2015-0008 Request for Records Disposition Authority Records Schedule Number DAA-0060-2015-0008 Schedule Status Modified Approved Version Agency or Establishment Department of Justice Record Group I Scheduling Group General Records of the Department of Justice Records Schedule applies to Major Subdivsion Major Subdivision Senior Leadership Offices Minor Subdivision Office of the Attorney General, Office of the Deputy Attorney General, Office of the Associate Attorney General Schedule Subject Electronic Records of the Attorney General, Deputy Attorney General, Associate Attorney General, and their program staffs from the administrations of Janet Reno (1993-2001 ), John Ashcroft (2001-2005), Alberto Gonzales (2005-2007), and Michael Mukasey (2007-2009). Internal agency concurrences will No be provided Background Information These records are legacy electronic records that do not fall under old, paper-based, non-media neutral schedules, nor do they fall under the 2010 media neutral schedule, which is for the administration of Eric Holder and forward. Item Count Number of Total Disposition Number of Permanent Number of Temporary Number of Withdrawn Items Disposition Items Disposition Items Disposition Items 1 1 0 0 GAO Approval Eleclronlc Records Archives Page 1 of& PDF Created on: 11/20/2017 NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION Request for Records DlsposlUon Aulharlty Records Schedule: DAA.OD&D.ZD15-0DD8 Outline of Records Schedule Items for DM-0060-2015-0008 Sequence Number 1 Electronic Records of the Attorney General, Deputy Attorney General, Associate A ttorney General, and their program staffs from the administrations of Janet Reno (1 993-2001), John Ashcroft (2001-2005), Alberto Gonzales (2005-2007), and Michae I Mukasey (2007-2009). -

Congressional Record—Senate S8167

December 5, 2011 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE S8167 EXECUTIVE SESSION ported by the Judiciary Committee on publican leadership at the end of last September 15 without opposition from year to refuse to agree to votes on a single member of the Committee, those nominations. That decision stood NOMINATION OF EDGARDO RAMOS Democratic or Republican. Mr. in stark contrast to the practice fol- TO BE UNITED STATES DISTRICT Furman, an experienced Federal pros- lowed by the Democratic majority in JUDGE FOR THE SOUTHERN DIS- ecutor who served as Counselor to At- the Senate during President Bush’s TRICT OF NEW YORK torney General Michael Mukasey for first two years. Last year, Senate Re- two years during the Bush Administra- publicans refused to use the same tion, is a nominee with an impressive standards for considering President NOMINATION OF ANDREW L. CAR- background and bipartisan support. Obama’s judicial nominees as we did TER, JR., TO BE UNITED STATES There is no reason or explanation for when the Senate gave up or down votes DISTRICT JUDGE FOR THE why the Senate could not also consider to all 100 of President Bush’s judicial SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW his nomination today. nominations reported by the Com- YORK There is also no reason or expla- mittee in his first two years. All 100 nation why Republican leadership will were confirmed before the end of the not consent to consider the other 20 ju- 107th Congress, including two con- NOMINATION OF JAMES RODNEY dicial nominations waiting for final troversial circuit court nominations GILSTRAP TO BE UNITED Senate action, all but four of which reported and then confirmed during the STATES DISTRICT JUDGE FOR were reported by the Committee with- lame duck session in 2002.