Ionad Cois Locha: 20 Years On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Donegal Winter Climbing

1 A climbers guide to Donegal Winter Climbing By Iain Miller www.uniqueascent.ie 2 Crag Index Muckish Mountain 4 Mac Uchta 8 Errigal 10 Maumlack 13 Poison Glen 15 Slieve Snaght 17 Horseshoe Corrie (Lough Barra) 19 Bluestacks (N) 22 Bluestacks (S) 22 www.uniqueascent.ie 3 Winter Climbing in Donegal. Winter climbing in the County of Donegal in the North West of Ireland is quite simply outstanding, alas it has a very fleeting window of opportunity. Due to it’s coastal position and relatively low lying mountains good winter conditions in Donegal are a rare commodity indeed. Usually temperatures have to be below 0 for 5 days consecutively, and down to -5 at night, and an ill timed dump of snow can spoil it all. To take advantage of these fleeting conditions you have to drop everything, and brave the inevitably appalling road conditions to get there, for be assured, it won’t last! When Donegal does come into prime Winter condition the crux of your days climbing will without a doubt be travelling by road throughout the county. In this guide I have tried to only use National primary and secondary roads as a means to travel and access. There are of course many regional and third class roads which provide much closer access to the mountains but under winter conditions these can very quickly become unpassable. The first recorded winter climbing I am aware of, was done in the Horsehoe Corrie in the early seventies and since then barely a couple of new routes have been logged anywhere in Donegal each decade since that! It was the winter of 2009/2010 that one of the coldest and longest winters in recorded history occurred with over 6 weeks of minus temperatures and snowdrifts of up to 12m in the Donegal uplands. -

![[BEGIN NICK LETHERT PART 01—Filename: A1005a EML Mmtc]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5265/begin-nick-lethert-part-01-filename-a1005a-eml-mmtc-175265.webp)

[BEGIN NICK LETHERT PART 01—Filename: A1005a EML Mmtc]

Nick Lethert Interview Narrator: Nick Lethert Interviewer: Dáithí Sproule Date: 1 December, 2017 DS: Dáithí Sproule NL: Nick Lethert [BEGIN NICK LETHERT PART 01—filename: A1005a_EML_mmtc] DS: Here we are – we are recording. It says “record” and the numbers are going up. This is myself and Nick Lethert making a second effort at our interview. It’s the first of December, isn’t it? NL: It is. DS: And we’re at the Celtic Junction. I suppose we’ll start at the same place as we started the last time, which was, I just think chronologically, and I think of, what is your background, what is the background of your father, your family, and origins, and your mother. NL: I grew up just down the street from the Celtic Junction in Saint Mark’s parish to a household where the first twelve or so years I lived with my father, who was of German Catholic heritage and my mother, who was Irish Catholic. Both of my mother’s parents came from Connemara. They met in Saint Paul, and I lived with my grandmother, who was from a little village, a tiny little village called Derroe, which is in Connemara over in the area by Carraroe, Costello, sort of bogland around there. My grandmother was a very intense person, not the least of which because her husband, who grew up in Maam Cross, a little further up in the mountains in Connemara, left her and the family when they had three young children, so it made for sort of a Dickens-like life for her and for her three kids, one of which was my mother. -

Make a Connection Déan Ceangal Share a Story Inis

SHARE A STORY MAKE A CONNECTION INIS SCÉAL DÉAN CEANGAL DONEGAL DHÚN NA NGALL EVENT GUIDE CLÁR IMEACHTAÍ Cover Photograph: St. Colmcille’s Arch is part of the archaeological complex at Disert in the foothills of the Bluestack Mountains of South Donegal and protected under the National Monuments Acts. The Disert Heritage Group and the Institute of Technology, Sligo will be leading a free guided tour of the Disert archaeological complex on Monday, August 20 as part of National Heritage Week. As part of the implementation of the County Donegal Heritage Plan, Donegal County Council in partnership with Derry City & Strabane District Council, Foras na Gaeilge and The Heritage Council has commissioned Abarta Heritage to undertake an audit of cultural heritage associated with St. Colmcille in preparation for the 1,500th anniversary of his birth in 2021. If you have information on, or are involved with, heritage sites, artefacts, archives or resources associated with St. Colmcille, please contact the County Donegal Heritage Office. The audit will be completed in mid-November 2018. Grianghraf ar an chlúdach: Tá Stua Cholm Cille mar chuid den choimpléasc seandálaíochta i nDíseart ag bunchnoic na gCruach Gorm i nDeisceart Dhún na nGall agus tá sé faoi chosaint ag Achtanna na Séadchomharthaí Náisiúnta. Beidh Cumann Oidhreachta Dhísirt agus an Institiúid Teicneolaíochta, Sligeach, i mbun turas treoraithe thart ar choimpléasc seandálaíochta Dhísirt Dé Luain, 20 Lúnasa mar chuid de Sheachtain Náisiúnta na hOidhreachta. Mar chuid de chur i bhfeidhm Phlean Oidhreachta Chontae Dhún na nGall, tá Abarta Heritage coimisiúnaithe ag Comhairle Contae Dhún na nGall, i gcomhpháirt le Comhairle Chathair Dhoire agus Cheantar an tSratha Báin, Foras na Gaeilge agus an Chomhairle Oidhreachta, le hiniúchadh a dhéanamh ar an oidhreacht chultúrtha atá bainte le Naomh Colm Cille mar ullmhúchán don bhliain 2021 nuair a bheas comóradh ar 1,500 bliain ón bhliain ar rugadh é. -

Troubled Voices Martin Dowling a Troubles Archive Essay

Troubled Voices A Troubles Archive Essay Martin Dowling Cover Image: Joseph McWilliams - Twelfth March (1991) From the collection of the Arts Council of Northern Ireland About the Author Martin Dowling is a historian, sociologist, and fiddle player, and lecturer in Irish Traditional Music in the School of Music and Sonic Arts in Queen’s University of Belfast. Martin has performed internationally with his wife, flute player and singer Christine Dowling. He teaches fiddle regularly at Scoil Samhradh Willy Clancy and the South Sligo Summer School, as well as at festivals and workshops in Europe and America. From 1998 until 2004 he was Traditional Arts Officer at the Arts Council of Northern Ireland. He is the author of Tenant Right and Agrarian Society in Ulster, 1600-1870 (Irish Academic Press, 1999), and has held postdoctoral fellowships in Queen’s University of Belfast and University College Dublin. Recent publications include “Fiddling for Outcomes: Traditional Music, Social Capital, and Arts Policy in Northern Ireland,” International Journal of Cultural Policy, vol. 14, no 2 (May, 2008); “’Thought-Tormented Music’: Joyce and the Music of the Irish Revival,” James Joyce Quarterly, vol. 44, no. 1 (2008); and “Rambling in the Field of Modern Identity: Some Speculations on Irish Traditional Music,” Radharc: a Journal of Irish and Irish-American Studies, vols. 5-7 (2004-2006), pp. 109-136. He is currently working on a monograph history of Irish traditional music from the death of harpist-composer Turlough Carolan (1738) to the first performance of Riverdance (1994). Troubled Voices Street singers and pedlars of broadsheets had for two centuries been important figures in Irish political and social life. -

AN INTRODUCTION to the ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE of COUNTY DONEGAL

AN INTRODUCTION TO THE ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE of COUNTY DONEGAL AN INTRODUCTION TO THE ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE of COUNTY DONEGAL COUNTY DONEGAL Mount Errigal viewed from Dunlewey. Foreword County Donegal has a rich architectural seventeenth-century Plantation of Ulster that heritage that covers a wide range of structures became a model of town planning throughout from country houses, churches and public the north of Ireland. Donegal’s legacy of buildings to vernacular houses and farm religious buildings is also of particular buildings. While impressive buildings are significance, which ranges from numerous readily appreciated for their architectural and early ecclesiastical sites, such as the important historical value, more modest structures are place of pilgrimage at Lough Derg, to the often overlooked and potentially lost without striking modern churches designed by Liam record. In the course of making the National McCormick. Inventory of Architectural Heritage (NIAH) The NIAH survey was carried out in phases survey of County Donegal, a large variety of between 2008 and 2011 and includes more building types has been identified and than 3,000 individual structures. The purpose recorded. In rural areas these include structures of the survey is to identify a representative as diverse as bridges, mills, thatched houses, selection of the architectural heritage of barns and outbuildings, gate piers and water Donegal, of which this Introduction highlights pumps; while in towns there are houses, only a small portion. The Inventory should not shopfronts and street furniture. be regarded as exhaustive and, over time, other A maritime county, Donegal also has a rich buildings and structures of merit may come to built heritage relating to the coast: piers, light. -

We Tour Everywhere! NO FLYING! 2015 Vacations TROPICANA Motorcoach • Air • Cruise $25 Slot P.O

NEW TOURS! 72 with Volume 24 January-December 2015 SAN ANTONIO, TEXAS HOLIDAY CHRISTMAS ON THE RIVER WALK See page 62 for description See page 105 for description This holiday season, the Riverwalk shines brighter than Grand Canadian ever as thousands of colorful Christmas lights decorate Circle Tour the facades and reflects off the river in San Antonio. Visit the famed Alamo, decorated for the holiday season, enjoy the relaxed holiday atmosphere while See page 95 for description being guided along by more than 6,000 luminaries during Fiesta de las Luminaries, and take a riverboat ride and admire the many holiday decorations from the water! PANAMA CANAL CRUISE We Tour Everywhere! NO FLYING! TROPICANA 2015 Vacations $25 Slot Motorcoach • Air • Cruise Play P.O. Box 348 • Hanover, MD 21076-0348 410-761-3757 1-800-888-1228 www.gunthercharters.com Restroom 57/56/55 14 54/53 52/51 13 50/49 48/47 12 46/45 44/43 11 42/41 40/39 10 38/37 36/35 9 34/33 32/31 8 30/29 28/27 7 26/25 24/23 6 22/21 20/19 5 18/17 16/15 4 14/13 12/11 3 10/9 8/7 2 6/5 4/3 1 2/1 Row # Door Side Driver Side 2 2 INTRODUCTION PLEASE READ THE FOLLOWING INFORMATION THOROUGHLY This section covers very important information and will answer many of your questions. Booking Your Tour Seating Information: 1. You must call to make your reservations, Monday 1. Passengers are assigned seats on all Gunther Tours. -

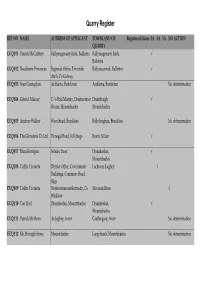

Quarry Register

Quarry Register REF NO NAME ADDRESS OF APPLICANT TOWNLAND OF Registered Status 3A 4A 5A NO ACTION QUARRY EUQY01 Patrick McCafferty Ballymagroarty Irish, Ballintra Ballymagroarty Irish, √ Ballintra EUQY02 Roadstone Provinces Regional Office, Two mile Ballynacarrick, Ballintra √ ditch, Co Galway EUQY03 Sean Granaghan Ardfarna, Bundoran Ardfarna, Bundoran No determination EUQY04 Gabriel Murray C/o Brid Murray, Drumconnor Drumbeagh, √ House, Mountcharles Mountcharles EUQY05 Andrew Walker Woodhead, Bruckless Ballyloughan, Bruckless No determination EUQY06 The Glenstone Co Ltd Donegal Road, Killybegs Bavin, Kilcar √ EUQY07 Brian Kerrigan Selacis, Inver Drumkeelan, √ Mountcharles EUQY08 Coillte Teoranta District Office, Government Lackrom, Laghey √ Buildings, Cranmore Road, Sligo EUQY09 Coillte Teoranta Newtownmountkennedy, Co Meenanellison √ Wicklow EUQY10 Con Friel Drumkeelan, Mountcharles Drumkeelan, √ Mountcharles EUQY11 Patrick Mulhern Ardaghey, Inver Castleogary, Inver No determination EUQY12 Mc Monagle Stone Mountcharles Largybrack, Mountcharles No determination Quarry Register REF NO NAME ADDRESS OF APPLICANT TOWNLAND OF Registered Status 3A 4A 5A NO ACTION QUARRY EUQY14 McMonagle Stone Mountcharles Turrishill, Mountcharles √ EUQY15 McMonagle Stone Mountcharles Alteogh, Mountcharles √ EUQY17 McMonagle Stone Mountcharles Glencoagh, Mountcharles √ EUQY18 McMonagle Stone Mountch arles Turrishill, Mountcharles √ EUQY19 Reginald Adair Bruckless Tullycullion, Bruckless √ EUQY21 Readymix (ROI) Ltd 5/23 East Wall Road, Dublin 3 Laghey √ EUQY22 -

Record of Protected Structures

RECORD OF PROTECTED STRUCTURES Glenties Electoral Area Ref. Name Description Address Number Electoral Area Rating Importance Value 40904202 Dunlewey House Detached early 19th century three-bay two-storey house with projecting open Dunlewey House, Glenties E.A. Regional AGSM porch, recessed two-storey wing to east, three-bay single-storey battlemented Dunlewey, Gweedore billiard room to west, two-storey wing to south, with two-and single-storey canted bay windows to west. 40902615 St John's Church Detached four-bay single-storey Church of Ireland Church, built 1752, with bell St. John's, Clondehorky Glenties E.A. National AIPSM cote to west gable Venetian east window, internal gallery, porch with staircase Parish, Ballymore to west and projecting gabled vestry to north-west corner. Lower, Creeslough 40903210 Carrickfin Church Detached three-bay single-storey Church of Ireland Chapel of Ease with gabled Carrickfin Church, Glenties E.A. Regional AHSM entrance porch, with bellcote to centre of south-west side and projecting sacristy Carrickfin, Kincasslagh, to north, built early 19th century. Letterkenny 40902601 St Michaels Church Detached Ronchamp-esque Catholic Church built 1970, with Baptistry, Blessed Creeslough Glenties E.A. National AP Sacrament Chapel, entrance porch, sacristy, confessionals and Marian chapel to perimeter. 40901501 Hornhead Bridge Twelve arch rubble stone road bridge over tidal stream built c.1800 with rubble Dunfanaghy Glenties E.A. Regional ATS stone segment arches; vaults, cutwaters, parapets, abutments and causeway to south. 40905802 Doocharry Bridge Road bridge over Gweebara river in two segmental-arched spans with custone Doocharry Bridge, Glenties E.A. Regional ATS voussoirs, dressed squared rubble stone haunched ashlar abutments and rubble Doochary stone parapets. -

Planning for Inclusion in County Donegal a Mapping Toolkit 2009

DONEGAL COUNTY DEVELOPMENT BOARDS Planning For Inclusion In County Donegal A Mapping Toolkit 2009 Donegal County Development Board Bord Forbartha Chontae Dhún na nGall FOREWORD CHAIRMAN OF Donegal COUNTY Development Board Following a comprehensive review of Donegal County Development Board’s ‘An Straitéis’ in 2009, it was agreed that the work of the Board would be concentrated on six key priority areas, one of which is on ‘Access to Services’. In this regard the goal of the Board is ‘to ensure best access to services for the community of Donegal’. As Chairperson of Donegal County Development Board, I am confident that the work contained in both of these documents will go a long way towards achieving an equitable distribution of services across the county in terms of informing the development of local and national plans as well as policy documents’ in both the Statistical and Mapping Documents. I would like to take this opportunity to thank all persons involved in the development of these toolkits including the agencies and officers who actively participated in Donegal County Development Board’s Social Inclusion Measures Group, Donegal County Council’s Social Inclusion Forum, Donegal County Councils Social Inclusion Unit and finally the Research and Policy Unit who undertook this work. There is an enormous challenge ahead for all of us in 2010, in ensuring that services are delivered in a manner that will address the needs of everyone in our community, especially the key vulnerable groups outlined in this document. I would urge all of the agencies, with a social inclusion remit in the county, to take cognisance of these findings with the end goal of creating a more socially inclusive society in Donegal in the future. -

Off the Beaten Track

Off the Beaten Track To have your recording considered for review in Sing Out!, please submit two copies (one for one of our reviewers and one for in- house editorial work, song selection for the magazine and eventual inclusion in the Sing Out! Resource Center, our multimedia, folk-related archive). All recordings received are included in Publication Noted (which follows Off the Beaten Track). Send two copies of your recording, and the appropriate background material, to Sing Out!, P.O. Box 5460 (for shipping: 512 E. Fourth St.), Bethlehem, PA 18015, Attention Off The Beaten Track. Sincere thanks to this issues panel of musical experts: Roger Dietz, Richard Dorsett, Tom Druckenmiller, Mark Greenberg, Victor K. Heyman, Stephanie P. Ledgin, John Lupton, Andy Nagy, Angela Page, Mike Regenstreif, Peter Spencer, Michael Tearson, Rich Warren, Matt Watroba, Elijah Wald, and Rob Weir. liant interpretation but only someone with not your typical backwoods folk musician, Jodys skill and knowledge could pull it off. as he studied at both Oberlin and the Cin- The CD continues in this fashion, go- cinnati College Conservatory of Music. He ing in and out of dream with versions of was smitten with the hammered dulcimer songs like Rhinordine, Lord Leitrim, in the early 70s and his virtuosity has in- and perhaps the most well known of all spired many players since his early days ballads, Barbary Ellen. performing with Grey Larsen. Those won- To use this recording as background derful June Appal recordings are treasured JODY STECHER music would be a mistake. I suggest you by many of us who were hearing the ham- Oh The Wind And Rain sit down in a quiet place, put on the head- mered dulcimer for the first time. -

Happy Christmas and Good Wishes for the Coming Year 2002

THE Happy Christmas and Good Wishes for the Coming Year 2002 Welcome to our first edition of The Creeslough View, which you will find is filled with memorabilia, nostalgia, heritage and local history, - the story of life presented by members of our community. The purpose of the Creeslough View is to give the locals an opportunity to document stories, poems, and old photographs to remind us now and again of our past on which we build our future. Because so much happens throughout the year in Creeslough it was felt it would be a shame not to document it. It is hoped the Creeslough View will enable smaller clubs and voluntary organisations to show off their achievements throughout the year. The social history of this locality has changed dramatically, but all the more is the need to record and acknowledge for tomorrow’s world, the spirit and common good, the close knit and dependence on others as a community, and the many characters who sustained it during the difficult times. We would like to thank each and every one of you that contributed to the Creeslough View. For the photographs and the stories, and a special thankyou to the sponsors for their generous support. I must also thank John Doak for all his work in preparing the material for printing. Because we received so much material for this edition, it was impossible to include it all. But rest assured it will be printed in the next edition next year. Again happy Christmas and thank you for purchasing the Creeslough View Declan Breslin 1 THE Muckish Mountain BY CHARLIE GALLAGHER "Muckish proud with her Muckish today has the same end a sand quarry. -

The Letterkenny & Burtonport Extension

L.6. 3 < m \J . 3 - 53 PP NUI MAYNOOTH OlltcisiE na r.£ir55n,i m & ft uac THE LETTERKENNY & BURTONPORT EXTENSION RAILWAY 1903-47: ITS SOCIAL CONTEXT AND ENVIRONMENT by FRANK SW EENEY THESES FOR THE DEGREE OF PH. D. DEPARTMENT OF MODERN HISTORY NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF IRELAND MAYNOOTH HEAD OF DEPARTMENT: Professor R. V. Comerford Supervisor of research: Professor R.V. Comerford October 2004 Volume 2 VOLUME 2 Chapter 7 In the shadow of the great war 1 Chapter 8 The War of Independence 60 Chapter 9 The Civil War 110 Chapter 10 Struggling under native rule 161 Chapter 11 Fighting decline and closure 222 Epilogue 281 Bibliography 286 Appendices 301 iv ILLUSTRATIONS VOLUME 2 Fig. 41 Special trains to and from the Letterkenny Hiring Fair 10 Fig. 42 School attendance in Gweedore and Cloughaneely 1918 12 Fig. 43 New fares Derry-Burtonport 1916 17 Fig. 44 Delays on Burtonport Extension 42 Fig. 45 Indictable offences committed in July 1920 in Co. Donegal 77 Fig. 46 Proposed wages and grades 114 Fig. 47 Irregular strongholds in Donegal 1922 127 Fig. 48 First count in Donegal General Election 1923 163 Fig. 49 Population trends 1911-1926 193 Fig. 50 Comparison of votes between 1923 and 1927 elections 204 Fig. 51 L&LSR receipts and expenses plus governments grants in 1920s 219 Fig. 52 New L&LSR timetable introduced in 1922 220 Fig. 53 Special trains to Dr McNeely’s consecration 1923 221 Fig. 54 Bus routes in the Rosses 1931 230 Fig. 55 Persons paid unemployment assistance 247 Fig.