Strengthening the Global Trade and Investment System for Sustainable Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Declaration of Jason Bartlett in Support of 86 MOTION For

Apple Inc. v. Samsung Electronics Co. Ltd. et al Doc. 88 Att. 34 Exhibit 34 Dockets.Justia.com Apple iPad review -- Engadget Page 1 of 14 Watch Gadling TV's "Travel Talk" and get all the latest travel news! MAIL You might also like: Engadget HD, Engadget Mobile and More MANGO PREVIEW WWDC 2011 E3 2011 COMPUTEX 2011 ASUS PADFONE GALAXY S II Handhelds, Tablet PCs Apple iPad review By Joshua Topolsky posted April 3rd 2010 9:00AM iPad Apple $499-$799 4/3/10 8/10 Finally, the Apple iPad review. The name iPad is a killing word -- more than a product -- it's a statement, an idea, and potentially a prime mover in the world of consumer electronics. Before iPad it was called the Best-in-class touchscreen Apple Tablet, the Slate, Canvas, and a handful of other guesses -- but what was little more than rumor Plugged into Apple's ecosystems and speculation for nearly ten years is now very much a reality. Announced on January 27th to a Tremendous battery life middling response, Apple has been readying itself for what could be the most significant product launch in its history; the making (or breaking) of an entirely new class of computer for the company. The iPad is No multitasking something in between its monumental iPhone and wildly successful MacBook line -- a usurper to the Web experience hampered by lack of Flash Can't stand-in for dedicated laptop netbook throne, and possibly a sign of things to come for the entire personal computer market... if Apple delivers on its promises. -

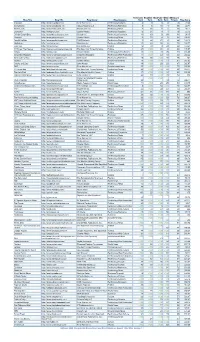

Blog Title Blog URL Blog Owner Blog Category Technorati Rank

Technorati Bloglines BlogPulse Wikio SEOmoz’s Blog Title Blog URL Blog Owner Blog Category Rank Rank Rank Rank Trifecta Blog Score Engadget http://www.engadget.com Time Warner Inc. Technology/Gadgets 4 3 6 2 78 19.23 Boing Boing http://www.boingboing.net Happy Mutants LLC Technology/Marketing 5 6 15 4 89 33.71 TechCrunch http://www.techcrunch.com TechCrunch Inc. Technology/News 2 27 2 1 76 42.11 Lifehacker http://lifehacker.com Gawker Media Technology/Gadgets 6 21 9 7 78 55.13 Official Google Blog http://googleblog.blogspot.com Google Inc. Technology/Corporate 14 10 3 38 94 69.15 Gizmodo http://www.gizmodo.com/ Gawker Media Technology/News 3 79 4 3 65 136.92 ReadWriteWeb http://www.readwriteweb.com RWW Network Technology/Marketing 9 56 21 5 64 142.19 Mashable http://mashable.com Mashable Inc. Technology/Marketing 10 65 36 6 73 160.27 Daily Kos http://dailykos.com/ Kos Media, LLC Politics 12 59 8 24 63 163.49 NYTimes: The Caucus http://thecaucus.blogs.nytimes.com The New York Times Company Politics 27 >100 31 8 93 179.57 Kotaku http://kotaku.com Gawker Media Technology/Video Games 19 >100 19 28 77 216.88 Smashing Magazine http://www.smashingmagazine.com Smashing Magazine Technology/Web Production 11 >100 40 18 60 283.33 Seth Godin's Blog http://sethgodin.typepad.com Seth Godin Technology/Marketing 15 68 >100 29 75 284 Gawker http://www.gawker.com/ Gawker Media Entertainment News 16 >100 >100 15 81 287.65 Crooks and Liars http://www.crooksandliars.com John Amato Politics 49 >100 33 22 67 305.97 TMZ http://www.tmz.com Time Warner Inc. -

Flickr: a Case Study of Web2.0, Aslib Proceedings, 60 (5), Pp

promoting access to White Rose research papers Universities of Leeds, Sheffield and York http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ This is an author produced version of a paper published in Aslib Proceedings. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/9043 Published paper Cox, A.M. (2008) Flickr: A case study of Web2.0, Aslib Proceedings, 60 (5), pp. 493-516 http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/00012530810908210 White Rose Research Online [email protected] Flickr: A case study of Web2.0 Andrew M. Cox University of Sheffield, UK [email protected] Abstract The “photosharing” site Flickr is one of the most commonly cited examples used to define Web2.0. This paper explores where Flickr’s real novelty lies, examining its functionality and its place in the world of amateur photography. The paper draws on a wide range of sources including published interviews with its developers, user opinions expressed in forums, telephone interviews and content analysis of user profiles and activity. Flickr’s development path passes from an innovative social game to a relatively familiar model of a website, itself developed through intense user participation but later stabilising with the reassertion of a commercial relationship to the membership. The broader context of the impact of Flickr is examined by looking at the institutions of amateur photography and particularly the code of pictorialism promoted by the clubs and industry during the C20th. The nature of Flickr as a benign space is premised on the way the democratic potential of photography is controlled by such institutions. -

UPDATED Activate Outlook 2021 FINAL DISTRIBUTION Dec

ACTIVATE TECHNOLOGY & MEDIA OUTLOOK 2021 www.activate.com Activate growth. Own the future. Technology. Internet. Media. Entertainment. These are the industries we’ve shaped, but the future is where we live. Activate Consulting helps technology and media companies drive revenue growth, identify new strategic opportunities, and position their businesses for the future. As the leading management consulting firm for these industries, we know what success looks like because we’ve helped our clients achieve it in the key areas that will impact their top and bottom lines: • Strategy • Go-to-market • Digital strategy • Marketing optimization • Strategic due diligence • Salesforce activation • M&A-led growth • Pricing Together, we can help you grow faster than the market and smarter than the competition. GET IN TOUCH: www.activate.com Michael J. Wolf Seref Turkmenoglu New York [email protected] [email protected] 212 316 4444 12 Takeaways from the Activate Technology & Media Outlook 2021 Time and Attention: The entire growth curve for consumer time spent with technology and media has shifted upwards and will be sustained at a higher level than ever before, opening up new opportunities. Video Games: Gaming is the new technology paradigm as most digital activities (e.g. search, social, shopping, live events) will increasingly take place inside of gaming. All of the major technology platforms will expand their presence in the gaming stack, leading to a new wave of mergers and technology investments. AR/VR: Augmented reality and virtual reality are on the verge of widespread adoption as headset sales take off and use cases expand beyond gaming into other consumer digital activities and enterprise functionality. -

Weekly Wireless Report September 23, 2016

Week Ending: Weekly Wireless Report September 23, 2016 This Week’s Stories Yahoo Says Information On At Least 500 Million User Accounts Inside This Issue: Was Stolen September 22, 2016 This Week’s Stories Yahoo Says Information On Internet company says it believes the 2014 hack was done by a state-sponsored actor; potentially the At Least 500 Million User biggest data breach on record. Accounts Was Stolen Yahoo Inc. is blaming “state-sponsored” hackers for what may be the largest-ever theft of personal You Can Now Exchange user data. Your Recalled Samsung Galaxy Note 7 The internet company, which has agreed to sell its core business to Verizon Communications Inc., said Products & Services Thursday that hackers penetrated its network in late 2014 and stole personal data on more than 500 million users. The stolen data included names, email addresses, dates of birth, telephone numbers Facebook Messenger Gets and encrypted passwords, Yahoo said. Polls And Now Encourages Peer-To-Peer Payments Yahoo said it believes that the hackers are no longer in its corporate network. The company said it Allo Brings Google’s didn't believe that unprotected passwords, payment-card data or bank-account information had been ‘Assistant’ To Your Phone affected. Today Computer users have grown inured to notices that a tech company, retailer or other company with Emerging Technology which they have done business had been hacked. But the Yahoo disclosure is significant because the iHeartRadio Is Finally company said it was the work of another nation, and because it raises questions about the fate of the Getting Into On-Demand $4.8 billion Verizon deal, which was announced on July 25. -

Sign up Now Or Login with Your Facebook Account'' - Look Familiar? You Can Now Do the Same Thing with Your Pinterest Account

Contact us Visit us Visit our website ''Sign up now or Login with your Facebook Account'' - Look familiar? You can now do the same thing with your Pinterest account. With this, users can easily Pin collections and oer some new ways to pin images. Right now this feature is only avail- able on two apps, but as Pinterest said, its early tests have shown that this integration increases shares to Pinterest boards by 132 percent. We can expect more apps will open up with this feature to nurture our Pinterest ob- session. View More Your Facebook's News Feed is like a billboard of your life and for years, it has been powered by automated software that tracks your actions to show you the posts you will most likely engage with, or as Facbook's FAQ said, ''the posts you will nd interesting''. But now you can say goodbye to guesswork. Facebook has cre- ated a new function called ''See First''. Simply add the Pages, friends or public gures’ proles to your See First list and it will revamp your News Feed Prefer- ences. Getting added to that list guarantees all their posts will appear at the top of a user’s News Feed with a blue star. View More Youku Tudou, which has been de- scribed as China’s answer to YouTube and boasts 185 million unique users per month, will air its rst foreign TV series approved under new rules from China’s media regulator, SAP- PRFT. The Korean romantic comedy entitled "Hyde, Jekyll, and Me'' will be available this weekend. -

Home Reviews Gear Gaming Entertainment Tomorrow Audio Video Deals Buyer's Guide

11/2/2020 MIT tests autonomous 'Roboat' that can carry two passengers | Engadget Login Home Reviews Gear Gaming Entertainment Tomorrow Audio Video Deals Buyer's Guide Log in Sign up 3 related articles Login https://www.engadget.com/mit-autonomous-roboat-ii-carries-passengers-140145138.html 1/10 11/2/2020 MIT tests autonomous 'Roboat' that can carry two passengers | Engadget Latest in Tomorrow Daimler and Volvo team up to make fuel cells for trucks and generators 1h ago Image credit: MIT Csail MIT tests autonomous 'Roboat' that can carry two passengers The half-scale Roboat II is being tested in Amsterdam's canals Nathan Ingraham 'Pristine' October 26, 2020 meteorite 2 255 may provide Comments Shares clues to the origins of our solar system 6h ago 3 related articles Login https://www.engadget.com/mit-autonomous-roboat-ii-carries-passengers-140145138.html 2/10 11/2/2020 MIT tests autonomous 'Roboat' that can carry two passengers | Engadget Disney robot with human- like gaze is equal parts uncanny and horrifying 10.31.20 Modified drones help scientists better predict volcanic eruptions MIT Csail 10.30.20 We’ve heard plenty about the potential of autonomous vehicles in recent years, but MIT is thinking about different forms of self-driving transportation. For the last five years, MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL) and the Senseable City Lab have been working on a fleet of autonomous boats to deploy in Amsterdam. Last year, we saw the autonomous “roboats” that could assemble themselves into a series of floating structures for various uses, and today CSAIL is unveiling the “Roboat II.” What makes this one particularly notable is that it’s the first that can carry passengers. -

Home Gear Gaming Entertainment Tomorrow the Buyer's Guide Video

12/23/2018 MIT can shrink 3D objects down to nanoscale versions Login Home Login Gear Gaming Entertainment Tomorrow3 related articles The Buyer's Guide Video Reviews Log in Sign up https://www.engadget.com/2018/12/17/mit-nanoscale-object-shrinking/ 1/14 12/23/2018 MIT can shrink 3D objects down to nanoscale versions Latest in Login Tomorrow 3 related articles The Morning After: Drone attacks and self-lacing Nikes 12.21.18 Image credit: Daniel Oran/MIT MIT can shrink 3D objects down to nanoscale versions It could be useful for tiny parts in robotics, medicine and beyond. Jon Fingas, @jonfingas 12.17.18 in Gadgetry President 10 631 poised to Comments Shares sign bill creating quantum computing initiative 12.20.18 Marlboro owner Sponsored Links by Taboola https://www.engadget.com/2018/12/17/mit-nanoscale-object-shrinking/ 2/14 12/23/2018 MIT can shrink 3D objects down to nanoscale versions invests Before you renew Amazon Prime, read this $12.8 billion in e- Login cigarette maker Juul 3 related aHrteircel’es sW hat Makes An Azure Free Account So Valuable... 12.20.18 You're Probably Overpaying at Amazon – This Genius Trick Will Fix That WMHoiicrknieobysuyoft Azure ILO tidies up your dab sessions with self- contained ceramic pellets 12.20.18 https://www.engadget.com/2018/12/17/mit-nanoscale-object-shrinking/ 3/14 12/23/2018 MIT can shrink 3D objects down to nanoscale versions Login 3 related articles Daniel Oran/MIT It's difficult to create nanoscale 3D objects. The techniques either tend to be slow (such as stacking layers of 2D etchings) or are limited to specific materials and shapes. -

Social Media Identity Deception Detection: a Survey

Social Media Identity Deception Detection: A Survey AHMED ALHARBI, HAI DONG, XUN YI, ZAHIR TARI, and IBRAHIM KHALIL, School of Computing Technologies, RMIT University, Australia Social media have been growing rapidly and become essential elements of many people’s lives. Meanwhile, social media have also come to be a popular source for identity deception. Many social media identity deception cases have arisen over the past few years. Recent studies have been conducted to prevent and detect identity deception. This survey analyses various identity deception attacks, which can be categorized into fake profile, identity theft and identity cloning. This survey provides a detailed review of social media identity deception detection techniques. It also identifies primary research challenges and issues in the existing detection techniques. This article is expected to benefit both researchers and social media providers. CCS Concepts: • Security and privacy ! Social engineering attacks; Social network security and privacy. Additional Key Words and Phrases: identity deception, fake profile, Sybil, sockpuppet, social botnet, identity theft, identity cloning, detection techniques ACM Reference Format: Ahmed Alharbi, Hai Dong, Xun Yi, Zahir Tari, and Ibrahim Khalil. 2021. Social Media Identity Deception Detection: A Survey . ACM Comput. Surv. 37, 4, Article 111 (January 2021), 35 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/ 1122445.1122456 1 INTRODUCTION Social media are web-based communication tools that facilitate people with creating customized user profiles to interact and share information with each other. Social media have been growing rapidly in the last two decades and have become an integral part of many people’s lives. Users in various social media platforms totalled almost 3.8 billion at the start of 2020, with a total growth of 321 million worldwide in the past 12 months1. -

Unmanned Vehicle Systems & Operations on Air, Sea, Land

Kansas State University Libraries New Prairie Press NPP eBooks Monographs 10-2-2020 Unmanned Vehicle Systems & Operations on Air, Sea, Land Randall K. Nichols Kansas State University Hans. C. Mumm Wayne D. Lonstein Julie J.C.H Ryan Candice M. Carter See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/ebooks Part of the Aerospace Engineering Commons, Aviation and Space Education Commons, Higher Education Commons, and the Other Engineering Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Nichols, Randall K.; Mumm, Hans. C.; Lonstein, Wayne D.; Ryan, Julie J.C.H; Carter, Candice M.; Hood, John-Paul; Shay, Jeremy S.; Mai, Randall W.; and Jackson, Mark J., "Unmanned Vehicle Systems & Operations on Air, Sea, Land" (2020). NPP eBooks. 35. https://newprairiepress.org/ebooks/35 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Monographs at New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in NPP eBooks by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Randall K. Nichols, Hans. C. Mumm, Wayne D. Lonstein, Julie J.C.H Ryan, Candice M. Carter, John-Paul Hood, Jeremy S. Shay, Randall W. Mai, and Mark J. Jackson This book is available at New Prairie Press: https://newprairiepress.org/ebooks/35 UNMANNED VEHICLE SYSTEMS & OPERATIONS ON AIR, SEA, LAND UNMANNED VEHICLE SYSTEMS & OPERATIONS ON AIR, SEA, LAND PROFESSOR RANDALL K. NICHOLS, JULIE RYAN, HANS MUMM, WAYNE LONSTEIN, CANDICE CARTER, JEREMY SHAY, RANDALL MAI, JOHN P HOOD, AND MARK JACKSON NEW PRAIRIE PRESS MANHATTAN, KS Copyright © 2020 Randall K. -

40 Lessons from 40 Years of Apple Ads

40 Lessons from 40 Years of Apple Ads Apple was founded on April fools day in 1976. It’s first office was Steve Jobs’ parents’ garage: And it’s first products were humble: Steve Jobs was obsessed with poets, and he and Woz both drew inspiration from one of the best, Bob Dylan. Any great folklorist will tell you that Apple’s origins met the primary criteria for future exaltation. They were humble, poor, and hard working. From those origins, Apple has grown to a global behemoth with over $269 billion dollars in the bank. One of the (many) things that helped Apple get to where it is today is a mastery of advertising. This article presents 40 of the best Apple ads over 40 years and draws 40 lessons from each. It spans 1977’s “Simplicity” all the way to “The Rock x Siri Dominate the Day.” 1977 — “Simplicity” (https://archive.org/details/Apple_II_-_Simplicity_is_the_ultimate_sophistication) “Apple II will change the way you think about computers.” This is an introduction to the Apple II. It displays the features of the device with a clear emphasis on personal computing. The idea of having a personal computer was very new at the time; many people didn’t think there was a use for a computer at home. The lesson: When you’re introducing something new, keep it simple. 1978 — “Bestselling” (http://www.macmothership.com/gallery/MiscAds/a2bestselling1.jpg) “Since we developed Apple II in April 1977, more people have chosen our computer than all other personal computers combined.” Apple opens the brochure with the above quote, providing social proof from buyers. -

Searchfactpack07 Bb.Qxp

A SUPPLEMENT TO FACT PACK 2007 IN ASSOCIATION WITH Published November 5, 2007 © Copyright 2007 Crain Communications Inc. MARKETING Search Marketing Fact Pack 2007 | Advertising Age | 3 SEARCH MARKETING THE WHO, WHAT, WHERE, WHEN OF SEARCH. AND HOW. SEARCH. BY NOW MARKETERS don’t need anyone to tell them that it’s important and that they should be paying attention to it. After all, search composes 40% of online ad spending and is becoming an ever-more-important driver of traffic across the web. Almost a quarter of September web traffic came from search engines, up from 20% last year (Page 20). Those trends mean there continues to be a thirst for quality information around the channel, what its major players are up to and how best to use it. In our annual Search Marketing Fact Pack, Ad Age culls much of that data into one handy guide that can sit on your desk all year long. (Download extra Fact Packs from the DataCenter at AdAge.com.) It’s been a year of big changes for major search engines. Yahoo in early 2007 rolled out its much-watched Panama search system, which factored in an ad’s relevancy as well as bid price to determine placement. Google introduced a universal search system that incorporated multiple media categories, such as images, video, local and books, into its results. And Ask.com garnered positive reviews for its new “Ask3D” system meant to help users find what they’re looking for faster. Profiles of the top five search players, starting on Page 10, outline each company’s financial and share results and what to watch for in the year ahead.