On Secular Stagnation in the Industrialized World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Commercial Real Estate Grapples with Going Green in Recession

Print California Real Estate Journal Online Article Page 1 of 4 California Real Estate Journal Newswire Articles www.carealestatejournal.com © 2009 The Daily Journal Corporation. All rights reserved. • select Print from the File menu above CREJ FRONT PAGE • Jan. 26, 2009 Commercial Real Estate Grapples With Going Green in Recession California developers and manufacturers await details of Obama's stimulus plan Developers and manufactures await details of Obama's stimulus plan By KEELEY WEBSTER CREJ Staff Writer Even as U.S. President Barack Obama has been making headlines for his "green team" and a proposal to invest $150 billion over the next 10 years in green energy, Hayward-based Optisolar was forced to lay off 130 employees, or 50 percent of its workforce. Optisolar Inc., a vertically integrated manufacturer of solar panels, is down, but not out. "We are hopeful that the new attitude in Washington will enable us to come out of this holding pattern," said Alan Bernheimer, the company's vice president of corporate communications. The employees who were laid off were hired to deal with the exponential growth the company was expecting after the interest in all-things-green took off and a series of federal, state and local policies and legislative initiatives took form to promote green business and development. But when Optisolar was not able to access the equity investment it needed for its planned manufacturing expansion, it was forced to trim staffing to what the current state of the business could support, Bernheimer said. That state includes a solar farm under construction in Canada. -

Ordinance No. 2015-37

ORDINANCE NO. 2015-37 ORDINANCE GRANTING AN EXCLUSIVE FRANCHISE TO PROGRESSIVE WASTE SOLUTIONS OF FL., INC., A FLORIDA CORPORATION, FOR THE COLLECTION OF RESIDENTIAL MUNICIPAL SOLID WASTE, AS THE COMPANY WITH THE HIGHEST RANKED BEST OVERALL PROPOSAL PURSUANT TO REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL NO. 2014-15-9500-00-002, FOR A TERM BEGINNING UPON EXECUTION OF THE EXCLUSIVE FRANCHISE AGREEMENT BY THE PARTIES AND ENDING ON SEPTEMBER 30, 2019, WITH AN AUTOMATIC RENEWAL TERM THEREAFTER OF FIVE YEARS, BEGINNING ON OCTOBER 1, 2019 AND ENDING ON SEPTEMBER 30, 2023, AND SUBSEQUENT RENEWALS AT THE OPTION OF THE PARTIES, FOR A TERM OF ONE YEAR EACH, WITH A CUMULATIVE DURATION OF ALL SUBSEQUENT RENEWALS AFTER THE FIRST RENEWAL TERM NOT EXCEEDING A TOTAL OF FIVE YEARS; APPROVING THE TERMS OF THE EXCLUSIVE FRANCHISE IN SUBSTANTIAL CONFORMITY WITH THE AGREEMENT ATTACHED HERETO AND MADE A PART HEREOF AS EXHIBIT '·t··; AND AUTHORIZING THE MAYOR AND THE CITY CLERK, AS ATTESTING WITNESS, ON BEHALF OF THE CITY, TO EXECUTE THE EXCLUSIVE FRANCHISE AGREEMENT; REPEALING ALL ORDINANCES OR PARTS OF ORDINANCES IN CONFLICT HEREWITH; PROVIDING PENALTIES FOR VIOLATION HEREOF; PROVIDING FOR A SEVERABILITY CLAUSE; AND PROVIDING FOR AN EFFECTIVE DATE. WHEREAS, the City issued a request for proposals ("'RFP") for certain types of Solid Waste Collection Services; and ORDINANCE NO. 2015-37 Page 2 WHEREAS, Progressive Waste Solutions of FL, Inc. ("'Progressive Waste") submitted a proposal in response to the City's RFP (RFP No. 2014-15-9500-00-002); and WHEREAS, the City has relied upon -

How Secular Is the Current Economic Stagnation?

How secular is the current economic stagnation? Maria Roubtsova ∗ September 30, 2016 Abstract From the burst of the dotcom bubble in 2000, until the global financial crisis that started in August 2007, the global economy was growing. During that phase, macroe- conomics went through an era of general optimism around the idea of having reached a great moderation, with high steady growth and low stable inflation. Central bankers thought they managed to dampen the economic cycles. This era came to an end fol- lowing the meltdown which started with the global financial crisis of 2007. And as among economic agents, macroeconomists’ general state of mind went from optimism to pessimism. Almost ten years since the beginning of the crisis, growth is not back to its pre-crisis trends. Therefore, macroeconomists are debating the notion of a secular stagnation. Is the economy on a long-term stagnation trend, if so, for what reasons, and how to address this situation? This paper offers a critical review of the debates among macroeconomists around this notion of secular stagnation, a concept which was invented by Alvin Hansen following the global economic crisis of the 1930s, and was brought back into the public debate largely by Lawrence Summers since the end of 2013. This literature review starts with a brief synthesis of the original debate about secular stagnation, launched by Hansen in 1938, and ended in the mid-1950s, since these debates inspired contemporary theorists. The second part highlights the main elements of neoclassical explanations for secular stagnation. The third part focuses on the Minskian idea of the end of a debt super-cycle. -

Super! Drama TV April 2021

Super! drama TV April 2021 Note: #=serial number [J]=in Japanese 2021.03.29 2021.03.30 2021.03.31 2021.04.01 2021.04.02 2021.04.03 2021.04.04 Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun 06:00 06:00 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:00 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:00 06:00 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:00 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:00 #15 #17 #19 #21 「The Long Morrow」 「Number 12 Looks Just Like You」 「Night Call」 「Spur of the Moment」 06:30 06:30 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 #16 06:30 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:30 06:30 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:30 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:30 「The Self-Improvement of Salvadore #18 #20 #22 Ross」 「Black Leather Jackets」 「From Agnes - With Love」 「Queen of the Nile」 07:00 07:00 CRIMINAL MINDS Season 10 07:00 CRIMINAL MINDS Season 10 07:00 07:00 STAR TREK Season 1 07:00 THUNDERBIRDS 07:00 #1 #2 #20 #19 「X」 「Burn」 「Court Martial」 「DANGER AT OCEAN DEEP」 07:30 07:30 07:30 08:00 08:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:00 08:00 ULTRAMAN towards the future 08:00 THUNDERBIRDS 08:00 10 10 #1 #20 #13「The Romance Recalibration」 #15「The Locomotion Reverberation」 「bitter harvest」 「MOVE- AND YOU'RE DEAD」 08:30 08:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:30 08:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:30 10 #14「The Emotion Detection 10 12 Automation」 #16「The Allowance Evaporation」 #6「The Imitation Perturbation」 09:00 09:00 information[J] 09:00 information[J] 09:00 09:00 information[J] 09:00 information[J] 09:00 09:30 09:30 THE GREAT 09:30 SUPERNATURAL Season 14 09:30 09:30 BETTER CALL SAUL Season 3 09:30 ZOEY’S EXTRAORDINARY -

Super! Drama TV December 2020 ▶Programs Are Suspended for Equipment Maintenance from 1:00-7:00 on the 15Th

Super! drama TV December 2020 ▶Programs are suspended for equipment maintenance from 1:00-7:00 on the 15th. Note: #=serial number [J]=in Japanese [D]=in Danish 2020.11.30 2020.12.01 2020.12.02 2020.12.03 2020.12.04 2020.12.05 2020.12.06 Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun 06:00 06:00 MACGYVER Season 2 06:00 MACGYVER Season 2 06:00 MACGYVER Season 2 06:00 MACGYVER Season 2 06:00 06:00 MACGYVER Season 3 06:00 BELOW THE SURFACE 06:00 #20 #21 #22 #23 #1 #8 [D] 「Skyscraper - Power」 「Wind + Water」 「UFO + Area 51」 「MacGyver + MacGyver」 「Improvise」 06:30 06:30 06:30 07:00 07:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:00 07:00 STAR TREK Season 1 07:00 STAR TREK: THE NEXT 07:00 Season 12 Season 12 Season 12 Season 12 #4 GENERATION Season 7 #7「The Grant Allocation Derivation」 #9 「The Citation Negation」 #11「The Paintball Scattering」 #13「The Confirmation Polarization」 「The Naked Time」 #15 07:30 07:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:30 information [J] 07:30 「LOWER DECKS」 07:30 Season 12 Season 12 Season 12 #8「The Consummation Deviation」 #10「The VCR Illumination」 #12「The Propagation Proposition」 08:00 08:00 SUPERNATURAL Season 11 08:00 SUPERNATURAL Season 11 08:00 SUPERNATURAL Season 11 08:00 SUPERNATURAL Season 11 08:00 08:00 THUNDERBIRDS ARE GO 08:00 STAR TREK: THE NEXT 08:00 #5 #6 #7 #8 Season 3 GENERATION Season 7 「Thin Lizzie」 「Our Little World」 「Plush」 「Just My Imagination」 #18「AVALANCHE」 #16 08:30 08:30 08:30 THUNDERBIRDS ARE GO 「THINE OWN SELF」 08:30 -

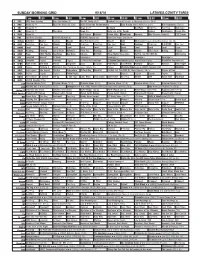

Sunday Morning Grid 9/18/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 9/18/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Cincinnati Bengals at Pittsburgh Steelers. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) (TVG) 2016 Evian Golf Championship Auto Racing Global RallyCross Series. Rio Paralympics (Taped) 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch BestPan! Paid Prog. Paid Prog. Skin Care 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) Vista L.A. at the Parade Explore Jack Hanna Ocean Mys. 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Amazing Why Pressure Cooker? CIZE Dance 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Good Day Game Day (N) Å 13 MyNet Arthritis? Matter Secrets Beauty Best Pan Ever! (TVG) Bissell AAA MLS Soccer Galaxy at Sporting Kansas City. (N) 18 KSCI Paid Prog. Paid Prog. Church Faith Paid Prog. Paid Prog. Paid Prog. AAA Cooking! Paid Prog. R.COPPER Paid Prog. 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR Painting Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexico Martha Ellie’s Real Baking Project 28 KCET Peep 1001 Nights Bug Bites Bug Bites Edisons Biz Kid$ Three Nights Three Days Eat Fat, Get Thin With Dr. ADD-Loving 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å 34 KMEX Conexión Pagado Secretos Pagado La Rosa de Guadalupe El Coyote Emplumado (1983) María Elena Velasco. -

Blanchard and Summers 1984 for the U.K., Germany and France; See Buiter 1985 for a More De- Tailed Study of U.K

This PDF is a selection from an out-of-print volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: NBER Macroeconomics Annual 1986, Volume 1 Volume Author/Editor: Stanley Fischer, editor Volume Publisher: MIT Press Volume ISBN: 0-262-06105-8 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/fisc86-1 Publication Date: 1986 Chapter Title: Hysteresis and the European Unemployment Problem Chapter Author: Olivier J. Blanchard, Lawrence H. Summers Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c4245 Chapter pages in book: (p. 15 - 90) — Olivier I. Blanchard andLawrenceH. Summers MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY AND NBER, HARVARD UNWERSITY AND NBER Hysteresis and the European Unemployment Problem After twenty years of negligible unemployment, most of Western Europe has since the early 1970s suffered a protracted period of high and ris- ing unemployment. In the United Kingdom unemployment peaked at 3.3 percent over the period 1945—1970, but has risen almost continu- ously since 1970, and now stands at over 12 percent. For the Common Market nations as a whole, the unemployment rate more than doubled between 1970 and 1980 and has doubled again since then. Few forecasts call for a significant decline in unemployment over the next several years, and none call for its return to levels close to those that prevailed in the 1950s and 1960s. These events are not easily accounted for by conventional classical or Keynesian macroeconomic theories. Rigidities associated with fixed- length contracts, or the costs of adjusting prices or quantities, are un- likely to be large enough to account for rising unemployment over periods of a decade or more. -

Some Political Economy of Monetary Rules

SUBSCRIBE NOW AND RECEIVE CRISIS AND LEVIATHAN* FREE! “The Independent Review does not accept “The Independent Review is pronouncements of government officials nor the excellent.” conventional wisdom at face value.” —GARY BECKER, Noble Laureate —JOHN R. MACARTHUR, Publisher, Harper’s in Economic Sciences Subscribe to The Independent Review and receive a free book of your choice* such as the 25th Anniversary Edition of Crisis and Leviathan: Critical Episodes in the Growth of American Government, by Founding Editor Robert Higgs. This quarterly journal, guided by co-editors Christopher J. Coyne, and Michael C. Munger, and Robert M. Whaples offers leading-edge insights on today’s most critical issues in economics, healthcare, education, law, history, political science, philosophy, and sociology. Thought-provoking and educational, The Independent Review is blazing the way toward informed debate! Student? Educator? Journalist? Business or civic leader? Engaged citizen? This journal is for YOU! *Order today for more FREE book options Perfect for students or anyone on the go! The Independent Review is available on mobile devices or tablets: iOS devices, Amazon Kindle Fire, or Android through Magzter. INDEPENDENT INSTITUTE, 100 SWAN WAY, OAKLAND, CA 94621 • 800-927-8733 • [email protected] PROMO CODE IRA1703 Some Political Economy of Monetary Rules F ALEXANDER WILLIAM SALTER n this paper, I evaluate the efficacy of various rules for monetary policy from the perspective of political economy. I present several rules that are popular in I current debates over monetary policy as well as some that are more radical and hence less frequently discussed. I also discuss whether a given rule may have helped to contain the negative effects of the recent financial crisis. -

Who Should Be the Next Fed Chairman?

A SYMPOSIUM OF VIEWS THE MAGAZINE OF INTERNATIONAL ECONOMIC POLICY 888 16th Street, N.W. Suite 740 Washington, D.C. 20006 Phone: 202-861-0791 Fax: 202-861-0790 www.international-economy.com [email protected] Who Should Over the next several years, commentators will speculate Be the on the identity of the next Chairman of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors once Alan Greenspan’s Next Fed tenure ends in 2006. Instead of speculation centered on who is likely to be next, per- haps the initial question should relate to who should Chairman? assume the post many describe today as “central banker to the world”? 44 THE INTERNATIONAL ECONOMY FALL 2004 TIE ASKED DOZENS OF EXPERTS Among those mentioned as possible replacements:* Bob Rubin Martin Feldstein Larry Summers Ben Bernanke William McDonough Joseph Stiglitz Lawrence B. Lindsey Robert McTeer Janet Yellen Glen Hubbard David Malpass Robert Barro Ian Macfarlane Bill Gross *Note: Selections made prior to November 2 U.S. presidential election. FALL 2004 THE INTERNATIONAL ECONOMY 45 BARNEY FRANK Member, U.S. House of Representatives, and senior GEORGE SOROS Democrat on the Financial Chairman, Soros Fund Services Committee Management f John Kerry is elected President, I will urge strongly Bob Rubin is by far the most qualified. the appointment of Nobel Prize winner Joseph Stiglitz Ito chair the Fed. That position has become the single most influential office affecting national economic pol- icy, and Stiglitz’s commitment to and understanding of the importance of combining economic growth with a concern for economic fairness are sorely needed. Given the increasing role that globalization plays, his interna- tional experience is also a great asset. -

Anticipation of Future Consumption: a Monetary Perspective

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Faria, Joao Ricardo; McAdam, Peter Working Paper Anticipation of future consumption: a monetary perspective ECB Working Paper, No. 1448 Provided in Cooperation with: European Central Bank (ECB) Suggested Citation: Faria, Joao Ricardo; McAdam, Peter (2012) : Anticipation of future consumption: a monetary perspective, ECB Working Paper, No. 1448, European Central Bank (ECB), Frankfurt a. M. This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/153881 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu WORKING PAPER SERIES NO 1448 / JULY 2012 ANTICIPATION OF FUTURE CONSUMPTION A MONETARY PERSPECTIVE by Joao Ricardo Faria and Peter McAdam In 2012 all ECB publications feature a motif taken from the €50 banknote. -

NCIS Comments on RMA's Second Draft of the 2011 SRA And

Response to the Risk Management Agency’s Second Draft of the Standard Reinsurance Agreement and Appendices Issued on February 23, 2010 Submitted by National Crop Insurance Services, Inc. On April 9, 2010 National Crop Insurance Services, Inc. 8900 Indian Creek Parkway, Suite 600 Overland Park, KS 66210-1567 National Crop Insurance Services, Inc. April 9, 2010 Contents Part Page 1. Overview……………………………………………………….. 3 2. Concerns with the Financial Provisions of the Second Draft.. 3 3. SRA Provisions………………………………………………… 26 National Crop Insurance Services, Inc. 2 April 9, 2010 1. Overview NCIS appreciates the ongoing efforts of USDA’s Risk Management Agency (RMA) to meet and discuss its second draft of the 2011 Standard Reinsurance Agreement (SRA) and the appendices. The industry continues to have serious problems with the second draft. With these comments, which include a new proposal for reinsurance terms of the SRA, and the negotiating meetings scheduled to take place soon, NCIS believes that a workable and mutually acceptable SRA and appendices can be developed. On February 17, 2010, RMA officials presented the key features of the financial provisions of the second draft of the SRA at the crop insurance industry’s annual meeting. On February 23, 2010, RMA released the text of the second draft, including the texts of draft Appendices I-IV, and requested comments by March 22, 2010 (Manager’s Bulletin No. MGR-10-002). On March 19, 2010, RMA extended the comment period to April 9, 2010 (Manager’s Bulletin No. MGR- 10-002.1). These comments are being provided in response to the April 9 call for comments on April 9. -

Meeting Minutes

DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY PRESIDENT’S ECONOMIC RECOVERY ADVISORY BOARD NOVEMBER 2, 2009 MEETING The meeting was convened at the White House pursuant to notice at 11:24 AM (EST). WHITE HOUSE ATTENDEES Barack Obama, President of the United States Rahm Emanuel, Chief of Staff Valerie Jarrett, Senior Advisor and Assistant to the President Lawrence Summers, Director, National Economic Council Carol Browner, Assistant to the President Austan Goolsbee, Staff Director and Chief Economist Jen Psaki, Deputy Press Secretary Adam Hitchcock, Office of the Chief of Staff ADVISORY BOARD MEMBERS PRESENT Paul Volcker, Chairman Anna Burger, Chair, Change to Win John Doerr, Partner, Kleiner, Perkins, Caufield & Byers William H. Donaldson, Former Chairman, SEC Roger W. Ferguson, Jr., President & CEO, TIAA-CREF Mark T. Gallogly, Founder & Managing Partner, Centerbridge Partners L.P. Jeff Immelt, Chairman & CEO, GE Monica C. Lozano, Publisher & Chief Executive Officer, La Opinion Charles E. Phillips, Jr., President, Oracle Corporation Penny Pritzker, Chairman & Founder, Pritzker Realty Group David F. Swensen, Chief Investment Officer, Yale University Richard L. Trumka, President, AFL-CIO Robert Wolf, Chairman & CEO, UBS Group Americas DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY ATTENDEES Timothy F. Geithner, Secretary of the Treasury Emanuel A. Pleitez, Designated Federal Officer The President's Economic Recovery Advisory Board (PERAB) held a meeting with the President to discuss long-term, innovation based ideas to sustain growth and continue to create jobs of the future at 11:24 AM (EST) on November 2, 2009 in the Roosevelt Room of the White House. In accordance with provisions of the Federal Advisory Committee Act, Public Law 92-463, and Federal Committee Management Regulations, 41 C.F.R.