Murad Giray and His Times

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dynamics of FM Frequencies Allotment for the Local Radio Broadcasting

DEVELOPMENT OF LOCAL RADIO BROADCASTING IN UKRAINE: 2015–2018 The Project of the National Council of Television and Radio Broadcasting of Ukraine “Community Broadcasting” NATIONAL COUNCIL MINISTRY OF OF TELEVISION AND RADIO INFORMATION POLICY BROADCASTING OF UKRAINE OF UKRAINE DEVELOPMENT OF LOCAL RADIO BROADCASTING: 2015—2018 Overall indicators As of 14 December 2018 local radio stations local radio stations rate of increase in the launched terrestrial broadcast in 24 regions number of local radio broadcasting in 2015―2018 of Ukraine broadcasters in 2015―2018 The average volume of own broadcasting | 11 hours 15 minutes per 24 hours Type of activity of a TV and radio organization For profit radio stations share in the total number of local radio stations Non-profit (communal companies, community organizations) radio stations share in the total number of local radio stations NATIONAL COUNCIL MINISTRY OF OF TELEVISION AND RADIO INFORMATION POLICY BROADCASTING OF UKRAINE OF UKRAINE DEVELOPMENT OF LOCAL RADIO BROADCASTING: 2015—2018 The competitions held for available FM radio frequencies for local radio broadcasting competitions held by the National Council out of 97 FM frequencies were granted to the on consideration of which local radio stations broadcasters in 4 format competitions, were granted with FM frequencies participated strictly by local radio stations Number of granted Number of general Number of format Practical steps towards implementation of the FM frequencies competitions* competitions** “Community Broadcasting” project The -

The Ukrainian Weekly 1992, No.26

www.ukrweekly.com Published by the Ukrainian National Association Inc.ic, a, fraternal non-profit association! ramian V Vol. LX No. 26 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY0, JUNE 28, 1992 50 cents Orthodox Churches Kravchuk, Yeltsin conclude accord at Dagomys summit by Marta Kolomayets Underscoring their commitment to signed by the two presidents, as well as Kiev Press Bureau the development of the democratic their Supreme Council chairmen, Ivan announce union process, the two sides agreed they will Pliushch of Ukraine and Ruslan Khas- by Marta Kolomayets DAGOMYS, Russia - "The agree "build their relations as friendly states bulatov of Russia, and Ukrainian Prime Kiev Press Bureau ment in Dagomys marks a radical turn and will immediately start working out Minister Vitold Fokin and acting Rus KIEV — As The Weekly was going to in relations between two great states, a large-scale political agreements which sian Prime Minister Yegor Gaidar. press, the Ukrainian Orthodox Church change which must lead our relations to would reflect the new qualities of rela The Crimea, another difficult issue in faction led by Metropolitan Filaret and a full-fledged and equal inter-state tions between them." Ukrainian-Russian relations was offi the Ukrainian Autocephalous Ortho level," Ukrainian President Leonid But several political breakthroughs cially not on the agenda of the one-day dox Church, which is headed by Metro Kravchuk told a press conference after came at the one-day meeting held at this summit, but according to Mr. Khasbu- politan Antoniy of Sicheslav and the conclusion of the first Ukrainian- beach resort, where the Black Sea is an latov, the topic was discussed in various Pereyaslav in the absence of Mstyslav I, Russian summit in Dagomys, a resort inviting front yard and the Caucasus circles. -

The Phenomenon of Transitivity in the Ukrainian Language

THE PHENOMENON OF TRANSITIVITY IN THE UKRAINIAN LANGUAGE 2 CONTENT INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………………… 3 Section 1. GENERAL CONCEPT OF TRANSITIVITY……………………. 8 Liudmyla Shytyk. CONCEPTS OF TRANSITIVITY IN LINGUISTICS……... 8 1.1. The meaning of the term «transition» and «transitivity»…………….. 8 1.2. Transitivity typology…………………………………………………... 11 1.3. The phenomenon of syncretism in the lingual plane…………………. 23 Section 2. TRANSITIVITY PHENOMENA IN THE UKRAINIAN LEXICOLOGY AND GRAMMAR…………………………………………... 39 Alla Taran. SEMANTIC TRANSITIVITY IN VOCABULARY……………… 39 Iryna Melnyk. TRANSPOSITIONAL PHENOMENA IN THE PARTS OF SPEECH SYSTEM……………………………………………………………… 70 Mykhailo Vintoniv. SYNCRETISM IN THE SYSTEM OF ACTUAL SENTENCE DIVISION………………………………………………………… 89 Section 3. TRANSITIVITY IN AREAL LINGUISTIC……………………... 114 Hanna Martynova. AREAL CHARAKTERISTIC OF THE MID-UPPER- DNIEPER DIALECT IN THE ASPECT OF TRANSITIVITY……………….... 114 3.1. Transitivity as areal issue……………………………………………… 114 3.2. The issue of boundary of the Mid-Upper-Dnieper patois…………….. 119 3.3. Transitive patois of Podillya-Mid-Upper-Dnieper boundary…………. 130 Tetiana Tyshchenko. TRANSITIVE PATOIS OF MID-UPPER-DNIEPER- PODILLYA BORDER………………………………………………………….. 147 Tetiana Shcherbyna. MID-UPPER-DNIEPER AND STEPPE BORDER DIALECTS……………………………………………………………………… 167 Section 4. THE PHENOMENA OF SYNCRETISM IN HISTORICAL PROJECTION…………………………………………………………………. 198 Vasyl Denysiuk. DUALIS: SYNCRETIC DISAPPEARANCE OR OFFICIAL NON-RECOGNITION………………………………………………………….. 198 Oksana Zelinska. LINGUAL MEANS OF THE REALIZATION OF GENRE- STYLISTIC SYNCRETISM OF A UKRAINIAN BAROQUE SERMON……. 218 3 INTRODUCTION In modern linguistics, the study of complex systemic relations and language dynamism is unlikely to be complete without considering the transitivity. Traditionally, transitivity phenomena are treated as a combination of different types of entities, formed as a result of the transformation processes or the reflection of the intermediate, syncretic facts that characterize the language system in the synchronous aspect. -

1 Introduction

State Service of Geodesy, Cartography and Cadastre State Scientific Production Enterprise “Kartographia” TOPONYMIC GUIDELINES For map and other editors For international use Ukraine Kyiv “Kartographia” 2011 TOPONYMIC GUIDELINES FOR MAP AND OTHER EDITORS, FOR INTERNATIONAL USE UKRAINE State Service of Geodesy, Cartography and Cadastre State Scientific Production Enterprise “Kartographia” ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Prepared by Nina Syvak, Valerii Ponomarenko, Olha Khodzinska, Iryna Lakeichuk Scientific Consultant Iryna Rudenko Reviewed by Nataliia Kizilowa Translated by Olha Khodzinska Editor Lesia Veklych ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ © Kartographia, 2011 ISBN 978-966-475-839-7 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction ................................................................ 5 2 The Ukrainian Language............................................ 5 2.1 General Remarks.............................................. 5 2.2 The Ukrainian Alphabet and Romanization of the Ukrainian Alphabet ............................... 6 2.3 Pronunciation of Ukrainian Geographical Names............................................................... 9 2.4 Stress .............................................................. 11 3 Spelling Rules for the Ukrainian Geographical Names....................................................................... 11 4 Spelling of Generic Terms ....................................... 13 5 Place Names in Minority Languages -

Proquest Dissertations

University of Alberta "The Biggest Calamity that Overshadowed All Other Calamities": Recruitment of Ukrainian "Eastern Workers" for the War Economy of the Third Reich, 1941-1944 by / ^.-.> S Taras Kurylo A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History and Classics Edmonton, Alberta Spring 2009 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-55416-6 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-55416-6 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

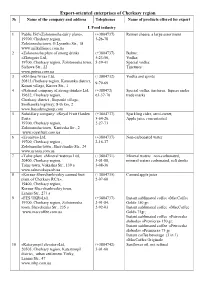

Export-Oriented Enterprises of Cherkasy Region № Name of the Company and Address Telephones Name of Products Offered for Export I

Export-oriented enterprises of Cherkasy region № Name of the company and address Telephones Name of products offered for export I. Food industry 1 Public JSC«Zolotonosha dairy plant», (+3804737) Rennet cheese, a large assortment 19700, Cherkasy region, 5-26-78 Zolotonosha town, G.Lysenko Str., 18 www.milkalliance.com.ua 2 «Zolotonosha plant of strong drinks (+3804737) Balms; «Zlatogor» Ltd, 5-23-50, Vodka; 19700, Cherkasy region, Zolotonosha town, 5-39-41 Special vodka; Sichova Str., 22 Tinctures www.petrus.com.ua 3 «Khlibna Niva» Ltd, (+3804732) Vodka and spirits 20813,Cherkasy region, Kamianka district, 9-79-69 Kosari village, Kirova Str., 1 4 «National company of strong drinks» Ltd, (+380472) Special vodka, tinctures, liquers under 19632, Cherkasy region, 63-37-70 trade marks Cherkasy district , Stepanki village, Smilianske highway, 8-th km, 2 www.bayaderagroup.com 5 Subsidiary company «Royal Fruit Garden (+3804737) Sparkling cider, semi-sweet; East», 5-64-26, Apple juice concentrated 19700, Cherkasy region, 2-27-73 Zolotonosha town, Kanivska Str., 2 www.royalfruit.com.ua 6 «Econiya» Ltd, (+3804737) Non-carbonated water 19700, Cherkasy region , 2-16-37 Zolotonosha town , Shevchenko Str., 24 www.econia.com.ua 7 «Talne plant «Mineral waters» Ltd, (+3804731) Mineral waters non-carbonated, 20400, Cherkasy region, 3-01-88, mineral waters carbonated, soft drinks Talne town, Voksalna Str., 139 а 3-08-36 www.talnovskaya.ub.ua 8 «Korsun-Shevchenkivskiy canned fruit (+3804735) Canned apple juice plant of Cherkasy RCA», 2-07-60 19400, Cherkasy -

The Fluvial Archive of the Middle and Lower Dnieper (A Review)

Netherlands Journal of Geosciences / Geologie en Mijnbouw 81 (3-4): 339-355 (2002) The fluvial archive of the Middle and Lower Dnieper (a review) A.V. Matoshko1, P.F. Gozhik2 & A.S. Ivchenko3 1 Corresponding author, Institute of Geological Sciences, National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, 55B Gonchara Street, 01054, Kiev. Ukraine. E-mail: [email protected] 2 P.F.Gozhik. Institute of Geological Sciences, National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, 55B Gonchara Street, 01054, Kiev. Ukraine. E-mail: [email protected] 3 A.S.Ivchenko. Institute of Geography, National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, 44, 3 Volodymyrska Street, 01034, Kiev. Ukraine. E-mail: [email protected] r ; Manuscript received: November 2000; accepted: January 2002 Abstract Information about the morphology and alluvial sediments of the Dnieper Valley is reviewed. The Dnieper Valley originated in the Late Miocene. The Middle Dnieper Valley is an intercontinental alluvial basin and the Lower Dnieper Valley is a shallow canyon that ends with a delta. Identification of the alluvial dynamic fades (channel, overbank, abandoned channel) is crucial for stratigraphical analysis. The dynamic fades form regular sequences - alluvial suites that combine into series. Individual suites and series are characterized by their mode of occurrence, fades composition, lithological features and expression in the modern landscape. Their stratigraphic position is established with reference to index beds and palaeontological, geochrono- logical and archaeological research, allowing them to be correlated along the valley. Correlation between different parts of the Dnieper system uses a combination of fades and geomorphological analyses, whereas correlation with other river systems makes use of mammalian and molluscan biostratigraphy. -

A Brief Note on Orthography and Transliteration

A Brief Note on Orthography and Transliteration Relationships to Khmelnytsky are as numerous as the names and orthographies that identify the hetman. In this volume, we have chosen to use the modified Ukrainian transliteration “Bohdan Khmelnytsky.” How- ever, where an author refers to a Polish text, we have used the standard Polish spelling, Bohdan Chmielnicki; Russian texts will refer to Bogdan Khmelʹnitskii, and Ukrainian-language texts follow the more standard transliteration of Bohdan Khmelʹnytsʹkyi. Names of places also necessarily vary according to the political moment or perspective in question. Wher- ever possible, we have attempted to standardize the spelling of place names to correspond to the time period and literary context under discussion. Where this is ambiguous, we have opted either for the standard spelling of well-known place names in English or for the present Ukrainian spelling. Names of well-known individuals likewise follow the English spelling of their names, whereas the names of less-commonly-translated writers con- form to either the Library of Congress (for Ukrainian and Russian) or the YIVO (for Hebrew and Yiddish) styles of transliteration. To ease pronun- ciation in our English-language narrative, we have modified the Russian and Ukrainian Library of Congress systems slightly by giving the initial vowel in all personal names as Yu, Ya, and Yo, rather than Iu, Ia, and Io. TABLE 0.1. Sample list of place names with linguistic variants Belarusian Polish Russian Ukrainian Yiddish Bielaja Carkava Biała Cerkiew -

Tetiana Yevsieieva the Activities of Ukraine's Union of Militant Atheists

Tetiana Yevsieieva The Activities of Ukraine’s Union of Militant Atheists during the Period of All-Out Collectivization, 1929–1933 The joint actions of the Communist Party leadership and local party organizations, trade unions, village councils, branches of the Committee of Poor Peasants, and organs of the State Political Administration (GPU—secret police) directed toward implementing all-out collectivization were unable to gain the support of the preponderant majority of Ukraine’s rural residents. It became necessary to devise another way of organizing the peasants that would allow the Soviet government to establish effective control over them. However, the experience of creating non- party peasant conferences in the 1920s had demonstrated convincingly the danger posed to the Soviet regime by the very existence of peasant associations, however varied in character. They inevitably turned into organizations that could compete successfully with the Russian Communist Party (Bolshevik).1 The Ukrainian historian Oksana Hanzha maintains that during the period in question the Bolsheviks still held the reins of power only because there were no other political organizations in the countryside empowered to legally manage affairs in rural areas. The Bolsheviks’ fear of losing control over rural regions was so great that they outlawed even the creation of poor peasant fractions at party conferences because the party’s Central Committee was convinced that they might turn into nuclei of peasant unions.2 Thus, assistance in accelerating the pace of -

Shooting Locations Guide Ukraine Contents

SHOOTING LOCATIONS GUIDE UKRAINE CONTENTS Cherkasy Oblast ........................................... 3 Chernihiv Oblast .......................................... 6 Chernivtsi Oblast .......................................... 9 Dnipro Oblast ............................................... 11 Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast ................................ 12 Kharkiv Oblast .............................................. 15 Kherson Oblast ............................................. 17 Khmelnytskyi Oblast .................................... 20 Kyiv Oblast .................................................... 22 Lviv Oblast ..................................................... 27 Mykolaiv Oblast ............................................ 31 Odesa Oblast ................................................ 33 Poltava Oblast ............................................... 35 Rivne Oblast ................................................ 36 Sumy Oblast ................................................ 38 Vinnytsia Oblast ............................................ 40 Volyn Oblast ................................................ 41 Zakarpattia Oblast ........................................ 43 Zaporizhzhia Oblast ..................................... 46 Zhytomyr Oblast ........................................... 48 Ternopil Oblast ............................................. 49 — Nature reserve — Biosphere reserve — Industry building — National park — Historical and cultural reserve CHERKASY OBLAST Local authorities Cherkasy city Council 36 Baidy Vyshnevetskoho -

The Ukrainian Weekly 1992

Published by the Ukrainian National Association Inc.ic, a, fraternal non-profit association! ramian V Vol. LX No. 26 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY0, JUNE 28, 1992 50 cents Orthodox Churches Kravchuk, Yeltsin conclude accord at Dagomys summit by Marta Kolomayets Underscoring their commitment to signed by the two presidents, as well as Kiev Press Bureau the development of the democratic their Supreme Council chairmen, Ivan announce union process, the two sides agreed they will Pliushch of Ukraine and Ruslan Khas- by Marta Kolomayets DAGOMYS, Russia - "The agree "build their relations as friendly states bulatov of Russia, and Ukrainian Prime Kiev Press Bureau ment in Dagomys marks a radical turn and will immediately start working out Minister Vitold Fokin and acting Rus KIEV — As The Weekly was going to in relations between two great states, a large-scale political agreements which sian Prime Minister Yegor Gaidar. press, the Ukrainian Orthodox Church change which must lead our relations to would reflect the new qualities of rela The Crimea, another difficult issue in faction led by Metropolitan Filaret and a full-fledged and equal inter-state tions between them." Ukrainian-Russian relations was offi the Ukrainian Autocephalous Ortho level," Ukrainian President Leonid But several political breakthroughs cially not on the agenda of the one-day dox Church, which is headed by Metro Kravchuk told a press conference after came at the one-day meeting held at this summit, but according to Mr. Khasbu- politan Antoniy of Sicheslav and the conclusion of the first Ukrainian- beach resort, where the Black Sea is an latov, the topic was discussed in various Pereyaslav in the absence of Mstyslav I, Russian summit in Dagomys, a resort inviting front yard and the Caucasus circles. -

Admin 2 Number of Partners with Ongoing

UKRAINE, Multipurpose Cash - Admin 2 Number of Partners with ongoing/completed Projects ( as of 2Sem8en iDvkaecembeSerre d2yna0-B1uda6) Novhorod-Siverskyi Yampil BELARUS Horodnia Ripky Shostka Liubeshiv Zarichne Ratne Snovsk Koriukivka Hlukhiv Kamin-Kashyrskyi Dubrovytsia Korop Shatsk Stara Chernihiv Sosnytsia Krolevets Volodymyrets Vyzhivka Kulykivka Mena Ovruch Putyvl Manevychi Sarny Rokytne Borzna Liuboml Kovel Narodychi Olevsk Konotop Buryn Bilopillia Turiisk Luhyny Krasiatychi Nizhyn Berezne Bakhmach Ivankiv Nosivka Rozhyshche Kostopil Yemilchyne Kozelets Sumy Volodymyr-Volynskyi Korosten Ichnia Talalaivka Nedryhailiv Lokachi Kivertsi Malyn Bobrovytsia Krasnopillia Romny RUSSIAN Ivanychi Lypova Lutsk Rivne Korets Novohrad-Volynskyi Borodianka Vyshhorod Pryluky Lebedyn FEDERATION Zdolbuniv Sribne Dolyna Sokal Mlyniv Radomyshl Brovary Zghurivka Demydivka Hoshcha Pulyny Cherniakhiv Makariv Trostianets Horokhiv Varva Dubno Ostroh Kyiv Baryshivka Lokhvytsia Radekhiv Baranivka Zhytomyr Brusyliv Okhtyrka Velyka Pysarivka Zolochiv Vovchansk Slavuta Boryspil Yahotyn Pyriatyn Chornukhy Hadiach Shepetivka Romaniv Korostyshiv Vasylkiv Bohodukhiv Velykyi Kamianka-buzka Radyvyliv Iziaslav Kremenets Fastiv Pereiaslav-Khmelnytskyi Hrebinka Zinkiv Krasnokutsk Burluk Bilohiria Polonne Chudniv Andrushivka Derhachi Zhovkva Busk Brody Shumsk Popilnia Obukhiv Myrhorod Kharkiv Liubar Berdychiv Bila Drabiv Kotelva Lviv Lanivtsi Kaharlyk Kolomak Valky Chuhuiv Dvorichna Troitske Zolochiv Tserkva Orzhytsia Khorol Dykanka Pechenihy Teofipol Starokostiantyniv