Why Do South Asian Documentaries Matter?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Studying Emotions in South Asia

South Asian History and Culture ISSN: (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rsac20 Studying emotions in South Asia Margrit Pernau To cite this article: Margrit Pernau (2021) Studying emotions in South Asia, South Asian History and Culture, 12:2-3, 111-128, DOI: 10.1080/19472498.2021.1878788 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/19472498.2021.1878788 © 2021 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group. Published online: 14 Feb 2021. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 1053 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rsac20 SOUTH ASIAN HISTORY AND CULTURE 2021, VOL. 12, NOS. 2–3, 111–128 https://doi.org/10.1080/19472498.2021.1878788 Studying emotions in South Asia Margrit Pernau Center for the History of Emotions, Max Planck Institute for Human Development, Berlin, Germany ABSTRACT Keywords Emotions are not a new comer in South Asian studies. Putting them centre Emotions; affects; theories of stage, however, allow for an increasing complexity and reflexivity in the emotions; methodology; categories we are researching: Instead of assuming that we already know South Asia what love, anger, or fear is and hence can use them to explain interactions and developments, the categories themselves have become open to inquiry. Emotions matter at three levels. They impact the way humans experience the world; they play an important role in the process through which individuals and social groups endow their experiences with mean ing; and they are important in providing the motivation to act in the world. -

Nationalism, Caste-Blindness, and the Continuing Problems of War-Displaced Panchamars in Post-War Jaffna Society

Article CASTE: A Global Journal on Social Exclusion Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 51–70 February 2020 brandeis.edu/j-caste ISSN 2639-4928 DOI: 10.26812/caste.v1i1.145 Nationalism, Caste-Blindness, and the Continuing Problems of War-Displaced Panchamars in Post-War Jaffna Society Kalinga Tudor Silva1 Abstract More than a decade after the end of the 26-year old LTTE—led civil war in Sri Lanka, a particular section of the Jaffna society continues to stay as Internally Displaced People (IDP). This paper tries to unravel why some low caste groups have failed to end their displacement and move out of the camps while everybody else has moved on to become a settled population regardless of the limitations they experience in the post-war era. Using both quantitative and qualitative data from the affected communities the paper argues that ethnic-biases and ‘caste-blindness’ of state policies, as well as Sinhala and Tamil politicians largely informed by rival nationalist perspectives are among the underlying causes of the prolonged IDP problem in the Jaffna Peninsula. In search of an appropriate solution to the intractable IDP problem, the author calls for an increased participation of these subaltern caste groups in political decision making and policy dialogues, release of land in high security zones for the affected IDPs wherever possible, and provision of adequate incentives for remaining people to move to alternative locations arranged by the state in consultation with IDPs themselves and members of neighbouring communities where they cannot be relocated at their original sites. Keywords Caste, caste-blindness, ethnicity, nationalism, social class, IDPs, Panchamars, Sri Lanka 1Department of Sociology, University of Peradeniya, Peradeniya, Sri Lanka E-mail: [email protected] © 2020 Kalinga Tudor Silva. -

Migrated Archives): Ceylon

Colonial administration records (migrated archives): Ceylon Following earlier settlements by the Dutch and Despatches and registers of despatches sent to, and received from, the Colonial Portuguese, the British colony of Ceylon was Secretary established in 1802 but it was not until the annexation of the Kingdom of Kandy in 1815 that FCO 141/2180-2186, 2192-2245, 2248-2249, 2260, 2264-2273: the entire island came under British control. In Open, confidential and secret despatches covering a variety of topics including the acts and ordinances, 1948, Ceylon became a self-governing state and a the economy, agriculture and produce, lands and buildings, imports and exports, civil aviation, railways, member of the British Commonwealth, and in 1972 banks and prisons. Despatches regarding civil servants include memorials, pensions, recruitment, dismissals it became the independent republic under the name and suggestions for New Year’s honours. 1872-1948, with gaps. The years 1897-1903 and 1906 have been of Sri Lanka. release in previous tranches. Below is a selection of files grouped according to Telegrams and registers of telegrams sent to and received from the Colonial Secretary theme to assist research. This list should be used in conjunction with the full catalogue list as not all are FCO 141/2187-2191, 2246-2247, 2250-2263, 2274-2275 : included here. The files cover the period between Open, confidential and secret telegrams on topics such as imports and exports, defence costs and 1872 and 1948 and include a substantial number of regulations, taxation and the economy, the armed forces, railways, prisons and civil servants 1899-1948. -

The Impacts of Small Arms Availability and Misuse in Sri Lanka

In the Shadow of a Cease-fire: The Impacts of Small Arms Availability and Misuse in Sri Lanka by Chris Smith October 2003 A publication of the Small Arms Survey Chris Smith The Small Arms Survey The Small Arms Survey is an independent research project located at the Graduate Institute of International Studies in Geneva, Switzerland. It is also linked to the Graduate Institute’s Programme for Strategic and International Security Studies. Established in 1999, the project is supported by the Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs, and by contributions from the Governments of Australia, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. It collaborates with research institutes and non-governmental organizations in many countries including Brazil, Canada, Georgia, Germany, India, Israel, Jordan, Norway, the Russian Federation, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Sweden, Thailand, the United Kingdom, and the United States. The Small Arms Survey occasional paper series presents new and substantial research findings by project staff and commissioned researchers on data, methodological, and conceptual issues related to small arms, or detailed country and regional case studies. The series is published periodically and is available in hard copy and on the project’s web site. Small Arms Survey Phone: + 41 22 908 5777 Graduate Institute of International Studies Fax: + 41 22 732 2738 47 Avenue Blanc Email: [email protected] 1202 Geneva Web site: http://www.smallarmssurvey.org Switzerland ii Occasional Papers No. 1 Re-Armament in Sierra Leone: One Year After the Lomé Peace Agreement, by Eric Berman, December 2000 No. 2 Removing Small Arms from Society: A Review of Weapons Collection and Destruction Programmes, by Sami Faltas, Glenn McDonald, and Camilla Waszink, July 2001 No. -

Majoritarian Politics in Sri Lanka: the ROOTS of PLURALISM BREAKDOWN

Majoritarian Politics in Sri Lanka: THE ROOTS OF PLURALISM BREAKDOWN Neil DeVotta | Wake Forest University April 2017 I. INTRODUCTION when seeking power; and the sectarian violence that congealed and hardened attitudes over time Sri Lanka represents a classic case of a country all contributed to majoritarianism. Multiple degenerating on the ethnic and political fronts issues including colonialism, a sense of Sinhalese when pluralism is deliberately eschewed. At Buddhist entitlement rooted in mytho-history, independence in 1948, Sinhalese elites fully economic grievances, politics, nationalism and understood that marginalizing the Tamil minority communal violence all interacting with and was bound to cause this territorialized community stemming from each other, pushed the island to eventually hit back, but they succumbed to towards majoritarianism. This, in turn, then led to ethnocentrism and majoritarianism anyway.1 ethnic riots, a civil war accompanied by terrorism What were the factors that motivated them to do that ultimately killed over 100,000 people, so? There is no single explanation for why Sri democratic regression, accusations of war crimes Lanka failed to embrace pluralism: a Buddhist and authoritarianism. revival in reaction to colonialism that allowed Sinhalese Buddhist nationalists to combine their The new government led by President community’s socio-economic grievances with Maithripala Sirisena, which came to power in ethnic and religious identities; the absence of January 2015, has managed to extricate itself minority guarantees in the Constitution, based from this authoritarianism and is now trying to on the Soulbury Commission the British set up revive democratic institutions promoting good prior to granting the island independence; political governance and a degree of pluralism. -

Draft Copy 3

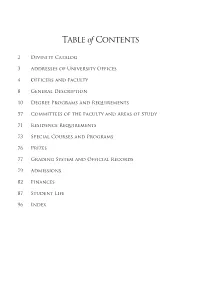

Table of Contents 2 Divinity Catalog 3 Addresses of University Offices 4 Officers and Faculty 8 General Description 10 Degree Programs and Requirements 57 Committees of the Faculty and Areas of Study 71 Residence Requirements 73 Special Courses and Programs 76 Prizes 77 Grading System and Official Records 79 Admissions 82 Finances 87 Student Life 96 Index 2 Divinity Catalog Divinity Catalog Announcements 2017-2018 More information regarding the University of Chicago Divinity School can be found online at http:// divinity.uchicago.edu. Or you may contact us at: Divinity School University of Chicago 1025 E. 58th St. Chicago, Illinois 60637 Telephone: 773-702-8200 Welcome to the University of Chicago Divinity School. In keeping with its long-standing traditions and policies, the University of Chicago considers students, employees, applicants for admission or employment, and those seeking access to University programs on the basis of individual merit. The University does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, national or ethnic origin, age, status as an individual with a disability, protected veteran status, genetic information, or other protected classes under the law (including Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972). For additional information regarding the University of Chicago’s Policy on Harassment, Discrimination, and Sexual Misconduct, please see: http://harassmentpolicy.uchicago.edu/page/policy. The University official responsible for coordinating compliance with this Notice of Nondiscrimination is Bridget Collier, Associate Provost and Director of the Office for Equal Opportunity Programs. Ms. Collier also serves as the University’s Title IX Coordinator, Affirmative Action Officer, and Section 504/ADA Coordinator. -

Freedom of Expression in Sri Lanka: How the Sri Lankan Constitution Fuels Self-Censorship and Hinders Reconciliation

Freedom of Expression in Sri Lanka: How the Sri Lankan Constitution Fuels Self-Censorship and Hinders Reconciliation By Clare Boronow Human Rights Study Project University of Virginia School of Law May 2012 Table of Contents I. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................ 1 II. FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION AND SELF -CENSORSHIP .................................................................... 3 A. Types of self-censorship................................................................................................... 4 1. Good self-censorship .................................................................................................... 4 2. Bad self-censorship....................................................................................................... 5 B. Self-censorship in Sri Lanka ............................................................................................ 6 III. SRI LANKA ’S CONSTITUTION FACILITATES THE VIOLATION OF FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION, THEREBY PROMOTING SELF -CENSORSHIP ............................................................................ 11 A. Express textual limitations on the freedom of expression.............................................. 11 B. The Constitution handcuffs the judiciary ....................................................................... 17 1. All law predating the 1978 Constitution is automatically valid ................................. 18 2. Parliament may enact unconstitutional -

An Anthropological Critique of Hate Speech Debates

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by SOAS Research Online International Journal of Communication 11(2017), 1173–1191 1932–8036/20170005 Extreme Speech Online: An Anthropological Critique of Hate Speech Debates MATTI POHJONEN Africa’s Voices Foundation, UK SAHANA UDUPA Central European University, Hungary Exploring the cases of India and Ethiopia, this article develops the concept of “extreme speech” to critically analyze the cultures of vitriolic exchange on Internet-enabled media. While online abuse is largely understood as “hate speech,” we make two interventions to problematize the presuppositions of this widely invoked concept. First, extreme speech emphasizes the need to contextualize online debate with an attention to user practices and particular histories of speech cultures. Second, related to context, is the ambiguity of online vitriol, which defies a simple antonymous conception of hate speech versus acceptable speech. The article advances this analysis using the approach of “comparative practice,” which, we suggest, complicates the discourse of Internet “risk” increasingly invoked to legitimate online speech restrictions. Keywords: online abuse, hate speech, India, Ethiopia, comparative practice, Internet risk The recent electoral victories for conservative groups with aggressive online presence have brought the political stakes of digital speech into sharp public focus, unsettling euphoric pronouncements on new media as a radical enabler of citizen participation and open society. Whether online Islamist radicalization or hate messages on social media during the 2016 refugee crisis, current developments have reinvigorated political debates on the limits of free speech online. The discourse on digital technologies has tilted toward the “dark side” of new media as a platform for promoting hate speech, fake news, right-wing nationalist mobilization, terrorism, misogyny, and intergroup conflict (Lovink, 2013; Morozov, 2012). -

SALA Summer 2008 Newsletter

Dept. of Humanities & Social Sciences, Indian Institute of Technology Roorkee (IITR) WINTER 2016 VOLUME 40 NO. 2 SALA President’s Column 1 PRESIDENT’S COLUMN SALA 2016 Conference Program 2-10 Salaam! Namaste! Howdy, ya’ll! On behalf of the executive commit- th MLA Panels of Interest/featuring SALA Members 10-11 tee, I extend a warm welcome to our 16 annual conference, in Austin, Texas, my home State! Over the past year, we have been preparing for Like Father, Like Son: A Dialogue with Professor Kamal 12-16 this moment. Co-Chairs Jana Fedtke and Abdollah “Abdy” Zahiri have Verma and Ambassador Richard Verma done an amazing job! When you get a chance, please thank them. Open Letters to the Modern Language Association 17-19 Also, thanks to Nalini Iyer, our outstanding secretary, Umme Al- (MLA) Wazedi, our adept treasurer, and to Aniruddha Mukhopadhyay, who SALA Member News 20 stepped in as the web manager when Madhurima Chakraborty stepped down. Thanks to them both for their efforts to make that transition seam- South Asian Review CFP, Regular Issue 2016 21 less. Kris Stokes continues to provide his web expertise, so that our web- site is useful and navigable. Summer Pervez has truly been a co-leader. Like Father, Like Son, continued 22-25 Rahul Gairola, editor of salaam, has continued to shape our newsletter into informative and relevant coherence. And, thanks to Melanie Wat- Other SALA 2016 announcements 23-25 tenbarger, for her work with the graduate caucus and a special task force. In Memoriam 26 Perhaps SALA's crown jewel, though, is our beloved Professor P. -

Contents V Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung in Southeast Asia Vii Editorial Axel Schmidt

Contents v Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung in Southeast Asia vii Editorial Axel Schmidt 1 Elections and Demoracy in Southeast Asia: Beyond the Ballot Box and Towards Governance Simon SC Tay and Tan Hsien-Li 29 Elections andDemoracy in Asia: India and Sri Lanka - Beyond the Ballot Box and Towards Governance Victor Ivan 39 Generation and Electoral Politics in South Korea Kang Won-Taek 53 The 2004 Election and Democracy in Malaysia Lim Hong Hai 63 Institutional Continuity and the 2004 Philippine Elections Julio C. Teehankee 69 Summary of the International Conference on 'Elections in Asia - Is Democracy Making Progress? Norbert von Hofmann 73 Women to Power in Asia's Election Year 2004? Andrea Fleschenerg 81 Programme and List of Participants iii Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung in Southeast Asia Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung has been present in Southeast Asia for more than 30 years. Its country offices in Bangkok, Jakarta, Manila and Hanoi have been active in implementing national cooperation programmes in partnership with parliaments, civil society groups and non-governmental organizations, academic institutions and ‘think-tanks’, government departments, political parties, women’s groups, trade unions, business associations and the media. In 1995, the Singapore office was transformed into an Office for Regional Cooperation in Southeast Asia. Its role is to support, in close cooperation with the country offices, ASEAN cooperation and integration, Asia-Europe dialogue and partnership, and country programmes in Cambodia and other ASEAN member states where there are no Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung offices. Its activities include dialogue programmes, international and regional conferences (e.g. on human rights, social policy, democratization, comprehensive security), Asia-Europe exchanges, civil education, scholarship programmes, research (social, economic and labour policies, foreign policy) as well as programmes with trade unions and media institutes. -

Cultural Citizenship and the Politics of Censorship in Post-Colonial India

Cultural Citizenship and the Politics of Censorship in Post-Colonial India: Media, Power, and the Making of the Citizen Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde Vorgelegt der Fakultät für Wirtschafts— und Sozialwissenschaften der Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg im Oktober 2013 von Lion König, M.A. Erstgutachter: Prof. Subrata K. Mitra, Ph.D. (Rochester) Zweitgutachterin: Prof. Dr. Christiane Brosius To the Citizens of India—legal as well as moral. Table of Contents List of Figures List of Tables List of Abbreviations Preface and Acknowledgments I. Introduction—Mapping the Field of Enquiry 13 1.1. Culture, Citizenship and Censorship: Building a Connective Structure 13 1.2. Core Question and Hypotheses 16 1.3. Citizenship and Cultural Citizenship: Conceptual Approaches 21 1.4. Overlaps between Citizenship and Culture in India 24 1.5. Culture: The Continuous Transformation of a Concept 28 1.6. Culture and Citizenship: Tracing Literary-Philosophical Linkages 29 1.7. Citizenship and the Media: Belonging through Representation 34 1.8. The Role of the Indian Mass Media in Nation-Building 37 1.8.1. Doordarshan and All India Radio 39 1.8.2. The Films Division 40 1.9. Media ‘from Below’: New Voices in the Discourse 42 II. Towards a New Paradigm—Bridging Political Science and Cultural Studies 46 2.1. Interdisciplinary Research: Opportunities and Challenges 46 2.2. Initiating a Dialogue between Political Science and Cultural Studies 48 2.3. Positivism: Striving for a Scientific Study of Politics 52 2.4. Beyond Positivism: A ‘Soft’ Political Science 55 2.5. Where Political Science and Cultural Studies meet: Sketching the Interface 59 2.6. -

Banned Films, C/Overt Oppression: Practices of Film Censorship from Contemporary Turkey

BANNED FILMS, C/OVERT OPPRESSION: PRACTICES OF FILM CENSORSHIP FROM CONTEMPORARY TURKEY A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by Sonay Ban December 2020 Examining Committee Members: Damien Stankiewicz, Advisory Chair, Anthropology Heather Levi, Anthropology Wazhmah Osman, Media Studies and Production Bilge Yeşil, External Member, College of Staten Island, CUNY ABSTRACT This project explores how film censorship shapes film production and circulation at film festivals, public screenings, and theatrical releases since the early 2000s in Turkey. It argues that, over time, mechanisms of censorship under Erdoğan’s authoritarian regime became less centralized; practices of censorship became more dispersed and less and less “official;” and the various imposing actors and agencies have differed from those in previous decades. Though still consistent with longstanding state ideologies, reasons for censorship practices, now more than ever, must be complexly navigated and negotiated by producers and distributors of film, including festival organizers, art institutions, and filmmakers themselves, through self-censorship. Drawing on a number of in-depth case studies of films banned after 2000, this project analyzes these works within the political and social contexts surrounding their releases, as well as ethnographic data based on dozens of extensive semi-structured interviews with cultural producers over five years of fieldwork. The corresponding