The Failure of Post-War Reconstruction in Jaffna, Sri Lanka: Indebtedness, Caste Exclusion and the Search for Alternatives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Test of Character for Jaffna Rivals for Sissies Was Perturbed Over a Comment St

Thursday 25th February, 2010 15 93rd Battle of the Golds Letter Shopping is A test of character for Jaffna rivals for Sissies was perturbed over a comment St. Patrick’s College Jaffna College made by Mr. Trevor Chesterfield in Ihis regular column in your esteemed newspaper on 22.02.2010. Writing about terrorism and its effect on sports he retraces the history particularly cricket, in the recent past. Then he directly refers to events that led to the boycott of World Cup match- es in Sri Lanka by Australia and West Indies. This is what he wrote: “Now Shane Warne is thinking about his options. He did the same in 1996 during the World Cup when both Australia and West Indies declined to Seated from left: A. M. Monoj, M. D. Sajeenthiran, S. Sahayaraj (PoG), P. Seated from left: M. Thileepan (Asst. Coach), S. Komalatharan, S. Niroshan, S. play their games in Colombo after the Navatheepan (Captain), Rev. Fr. Gero Selvanayaham (Rector), S. Milando Jenifer (V. Seeralan (V. Capt), B. L. Mohanakumar (Physical Director), N. A. Wimalendran truck bomb at the Central Bank. Capt), P. Jeyakumar (MiC), A. S. Nishanthan (Coach), B. Michael Robert, M. V. (Principal), P. Srikugan (Captain), J. Nigethan, B. Prasad, R. Kugan (Coach). Typically,politicians opened their jaws Hamilton. Standing from left: Marino Sanjay, G. Tishanth Tuder, J. Livington, V. Standing from left: S. Vishnujan, P. Sobinathsuvan, R. Bentilkaran, K. Trasopanan, and one crassly suggested how in ref- Kuhabala, A. M. Nobert, G. Morison, Erik Prathap, V. Jehan Regilus, R. Ajith Darwin, T. Priyalakshan, N. Bengamin Nirushan, S. -

Studying Emotions in South Asia

South Asian History and Culture ISSN: (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rsac20 Studying emotions in South Asia Margrit Pernau To cite this article: Margrit Pernau (2021) Studying emotions in South Asia, South Asian History and Culture, 12:2-3, 111-128, DOI: 10.1080/19472498.2021.1878788 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/19472498.2021.1878788 © 2021 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group. Published online: 14 Feb 2021. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 1053 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rsac20 SOUTH ASIAN HISTORY AND CULTURE 2021, VOL. 12, NOS. 2–3, 111–128 https://doi.org/10.1080/19472498.2021.1878788 Studying emotions in South Asia Margrit Pernau Center for the History of Emotions, Max Planck Institute for Human Development, Berlin, Germany ABSTRACT Keywords Emotions are not a new comer in South Asian studies. Putting them centre Emotions; affects; theories of stage, however, allow for an increasing complexity and reflexivity in the emotions; methodology; categories we are researching: Instead of assuming that we already know South Asia what love, anger, or fear is and hence can use them to explain interactions and developments, the categories themselves have become open to inquiry. Emotions matter at three levels. They impact the way humans experience the world; they play an important role in the process through which individuals and social groups endow their experiences with mean ing; and they are important in providing the motivation to act in the world. -

The Case of Kataragama Pāda Yātrā in Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka Journal of Social Sciences 2017 40 (1): 41-52 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4038/sljss.v40i1.7500 RESEARCH ARTICLE Collective ritual as a way of transcending ethno-religious divide: the case of Kataragama Pāda Yātrā in Sri Lanka# Anton Piyarathne* Department of Social Studies, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, The Open University of Sri Lanka, Nawala, Sri Lanka. Abstract: Sri Lanka has been in the prime focus of national and who are Sinhala speakers, are predominantly Buddhist, international discussions due to the internal war between the whereas the ethnic Tamils, who communicate in the Tamil Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) and the Sri Lankan language, are primarily Hindu. These two ethnic groups government forces. The war has been an outcome of the are often recognised as rivals involved in an “ethnic competing ethno-religious-nationalisms that raised their heads; conflict” that culminated in war between the LTTE (the specially in post-colonial Sri Lanka. Though today’s Sinhala Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam, a military movement and Tamil ethno-religious-nationalisms appear as eternal and genealogical divisions, they are more of constructions; that has battled for the liberation of Sri Lankan Tamils) colonial inventions and post-colonial politics. However, in this and the government. Sri Lanka suffered heavily as a context it is hard to imagine that conflicting ethno-religious result of a three-decade old internal war, which officially groups in Sri Lanka actually unite in everyday interactions. ended with the elimination of the leadership of the LTTE This article, explains why and how this happens in a context in May, 2009. -

Socio-Religious Desegregation in an Immediate Postwar Town Jaffna, Sri Lanka

Carnets de géographes 2 | 2011 Espaces virtuels Socio-religious desegregation in an immediate postwar town Jaffna, Sri Lanka Delon Madavan Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/cdg/2711 DOI: 10.4000/cdg.2711 ISSN: 2107-7266 Publisher UMR 245 - CESSMA Electronic reference Delon Madavan, « Socio-religious desegregation in an immediate postwar town », Carnets de géographes [Online], 2 | 2011, Online since 02 March 2011, connection on 07 May 2019. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/cdg/2711 ; DOI : 10.4000/cdg.2711 La revue Carnets de géographes est mise à disposition selon les termes de la Licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Socio-religious desegregation in an immediate postwar town Jaffna, Sri Lanka Delon MADAVAN PhD candidate and Junior Lecturer in Geography Université Paris-IV Sorbonne Laboratoire Espaces, Nature et Culture (UMR 8185) [email protected] Abstract The cease-fire agreement of 2002 between the Sri Lankan state and the separatist movement of Liberalisation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), was an opportunity to analyze the role of war and then of the cessation of fighting as a potential process of transformation of the segregation at Jaffna in the context of immediate post-war period. Indeed, the armed conflict (1987-2001), with the abolition of the caste system by the LTTE and repeated displacements of people, has been a breakdown for Jaffnese society. The weight of the hierarchical castes system and the one of religious communities, which partially determine the town's prewar population distribution, the choice of spouse, social networks of individuals, values and taboos of society, have been questioned as a result of the conflict. -

CHAP 9 Sri Lanka

79o 00' 79o 30' 80o 00' 80o 30' 81o 00' 81o 30' 82o 00' Kankesanturai Point Pedro A I Karaitivu I. Jana D Peninsula N Kayts Jana SRI LANKA I Palk Strait National capital Ja na Elephant Pass Punkudutivu I. Lag Provincial capital oon Devipattinam Delft I. Town, village Palk Bay Kilinochchi Provincial boundary - Puthukkudiyiruppu Nanthi Kadal Main road Rameswaram Iranaitivu Is. Mullaittivu Secondary road Pamban I. Ferry Vellankulam Dhanushkodi Talaimannar Manjulam Nayaru Lagoon Railroad A da m' Airport s Bridge NORTHERN Nedunkeni 9o 00' Kokkilai Lagoon Mannar I. Mannar Puliyankulam Pulmoddai Madhu Road Bay of Bengal Gulf of Mannar Silavatturai Vavuniya Nilaveli Pankulam Kebitigollewa Trincomalee Horuwupotana r Bay Medawachchiya diya A d o o o 8 30' ru 8 30' v K i A Karaitivu I. ru Hamillewa n a Mutur Y Pomparippu Anuradhapura Kantalai n o NORTH CENTRAL Kalpitiya o g Maragahewa a Kathiraveli L Kal m a Oy a a l a t t Puttalam Kekirawa Habarane u 8o 00' P Galgamuwa 8o 00' NORTH Polonnaruwa Dambula Valachchenai Anamaduwa a y O Mundal Maho a Chenkaladi Lake r u WESTERN d Batticaloa Naula a M uru ed D Ganewatta a EASTERN g n Madura Oya a G Reservoir Chilaw i l Maha Oya o Kurunegala e o 7 30' w 7 30' Matale a Paddiruppu h Kuliyapitiya a CENTRAL M Kehelula Kalmunai Pannala Kandy Mahiyangana Uhana Randenigale ya Amparai a O a Mah Reservoir y Negombo Kegalla O Gal Tirrukkovil Negombo Victoria Falls Reservoir Bibile Senanayake Lagoon Gampaha Samudra Ja-Ela o a Nuwara Badulla o 7 00' ng 7 00' Kelan a Avissawella Eliya Colombo i G Sri Jayewardenepura -

Urban Transport System Development Project for Colombo Metropolitan Region and Suburbs

DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT URBAN TRANSPORT SYSTEM DEVELOPMENT PROJECT FOR COLOMBO METROPOLITAN REGION AND SUBURBS URBAN TRANSPORT MASTER PLAN FINAL REPORT TECHNICAL REPORTS AUGUST 2014 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY EI ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. JR 14-142 DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT URBAN TRANSPORT SYSTEM DEVELOPMENT PROJECT FOR COLOMBO METROPOLITAN REGION AND SUBURBS URBAN TRANSPORT MASTER PLAN FINAL REPORT TECHNICAL REPORTS AUGUST 2014 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT URBAN TRANSPORT SYSTEM DEVELOPMENT PROJECT FOR COLOMBO METROPOLITAN REGION AND SUBURBS Technical Report No. 1 Analysis of Current Public Transport AUGUST 2014 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY (JICA) ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. URBAN TRANSPORT SYSTEM DEVELOPMENT PROJECT FOR COLOMBO METROPOLITAN REGION AND SUBURBS Technical Report No. 1 Analysis on Current Public Transport TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 Railways ............................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 History of Railways in Sri Lanka .................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Railway Lines in Western Province .............................................................................................. 5 1.3 Train Operation ............................................................................................................................ -

The Household Water Usage Community Awareness Regarding

Original Article DOI: http://doi.org/10.4038/jmj.v32i1.90 The household water usage Community awareness regarding water pollution and factors associated with it among adult residents in MOH area, Uduvil 1Rajeev G , 2Murali V 1 RDHS Jaffna,2 Ministry of Health Abstract Introduction Introduction: Water pollution is a one of the Water is the driving force of nature and most public health burdens and the consumption of important natural resource that permeates all contaminated water has adverse health effects and aspects of the life on Earth. It is essential for even affects fetal development. The objective was human health and contributes to the sustainability to describe the household water usage pattern, of ecosystems. Safe water access and adequate community awareness of water pollution and sanitation are two basic determinants of good health factors associated with it among adult residents in (1). Both of these are important to protect people MOH area, Uduvil. from water related diseases like diarrhoeal diseases and typhoid (2). Method: A descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted on a community-based sample Clean drinking water is important for overall health of 817 adult residents with multi stage cluster and plays a substantial role in health of children sampling method. The data was collected by and their survival. Giving access to safe water is an interviewer administered questionnaire. one of the most effective ways to promote health Statistically significance for selected factors and and reduce poverty. All have the right to access awareness were analyzed with chi square and enough, continuous, safe, physically accessible, Mann-Whitney U test. -

Sri Lanka – Tamils – Eastern Province – Batticaloa – Colombo

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: LKA34481 Country: Sri Lanka Date: 11 March 2009 Keywords: Sri Lanka – Tamils – Eastern Province – Batticaloa – Colombo – International Business Systems Institute – Education system – Sri Lankan Army-Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam conflict – Risk of arrest This response was prepared by the Research & Information Services Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. This research response may not, under any circumstance, be cited in a decision or any other document. Anyone wishing to use this information may only cite the primary source material contained herein. Questions 1. Please provide information on the International Business Systems Institute in Kaluvanchikkudy. 2. Is it likely that someone would attain a high school or higher education qualification in Sri Lanka without learning a language other than Tamil? 3. Please provide an overview/timeline of relevant events in the Eastern Province of Sri Lanka from 1986 to 2004, with particular reference to the Sri Lankan Army (SLA)-Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) conflict. 4. What is the current situation and risk of arrest for male Tamils in Batticaloa and Colombo? RESPONSE 1. Please provide information on the International Business Systems Institute in Kaluvanchikkudy. Note: Kaluvanchikkudy is also transliterated as Kaluwanchikudy is some sources. No references could be located to the International Business Systems Institute in Kaluvanchikkudy. The Education Guide Sri Lanka website maintains a list of the “Training Institutes Registered under the Ministry of Skills Development, Vocational and Tertiary Education”, and among these is ‘International Business System Overseas (Pvt) Ltd’ (IBS). -

Engaging the Tamil Diaspora in Peace-Building Efforts in Sri Lanka Michael Potters

Undergraduate Transitional Justice Review Volume 1 | Issue 3 Article 5 2010 Engaging the Tamil Diaspora in Peace-Building Efforts in Sri Lanka Michael Potters Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/undergradtjr Recommended Citation Potters, Michael (2010) "Engaging the Tamil Diaspora in Peace-Building Efforts in Sri Lanka," Undergraduate Transitional Justice Review: Vol. 1 : Iss. 3 , Article 5. Available at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/undergradtjr/vol1/iss3/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Transitional Justice Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Potters: Engaging the Tamil Diaspora in Peace-Building Efforts in Sri Lank ENGAGING THE TAMIL DIASPORA IN PEACE-BUILDING EFFORTS IN SRI LANKA Michael Potters Refugees who have fled the conflict in Sri Lanka have formed large diaspora communities across the globe, forming one of the largest in Toronto, Canada. Members of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) have infiltrated these communities and elicited funding from its members, through both coercion and consent, to continue the fight in their home country. This paper will outline the importance of including these diaspora communities in peace-building efforts, and will propose a three-tier solution to enable these contributions. On the morning of October 17, 2009, Canadian authorities seized the vessel Ocean Lady off the coast of British Columbia, Canada. The ship had entered Canadian waters with 76 Tamil refugees on board, fleeing persecution and violence in the aftermath of Sri Lanka’s long and violent civil war. -

Characterization of Irrigation Water Quality of Chunnakam Aquifer in Jaffna Peninsula

Tropical Agricultural Research Vol. 23 (3): 237 – 248 (2012) Characterization of Irrigation Water Quality of Chunnakam Aquifer in Jaffna Peninsula A. Sutharsiny, S. Pathmarajah1*, M. Thushyanthy2 and V. Meththika3 Postgraduate Institute of Agriculture University of Peradeniya Sri Lanka ABSTRACT. Chunnakam aquifer is the main lime stone aquifer of Jaffna Peninsula. This study focused on characterization of Chunnakam aquifer for its suitability for irrigation. Groundwater samples were collected from wells to represent different uses such as domestic, domestic with home garden, public wells and farm wells during January to April 2011. Important chemical parameters, namely electrical conductivity (EC), chloride, calcium, magnesium, carbonate, bicarbonate, sulfate, sodium and potassium were determined in water samples from 44 wells. Sodium percentage, Sodium adsorption ratio (SAR), and residual Sodium Carbonate (RSC) levels were calculated using standard equations to map the spatial variation of irrigation water quality of the aquifer using GIS. Groundwater was classified based on Chadha diagram and US salinity diagram. Two major hydro chemical facies Ca-Mg-Cl-SO4 and Na-Cl-SO4 were identified using Chadha diagram. Accordingly, it indicates permanent hardness and salinity problems. Based on EC, 16 % of the monitored wells showed good quality and 16 % showed unsuitable water for irrigation. Based on sodium percentage, 7 % has excellent and 23 % has doubtful irrigation water quality. However, according to SAR and RSC values, most of the wells have water good for irrigation. US salinity hazard diagram showed, 16 % as medium salinity and low alkali hazard. These groundwater sources can be used to irrigate all types of soils with little danger of increasing exchangeable sodium in soil. -

Volume V, Issues 3-4 September 2011 PERSPECTIVES on TERRORISM Volume 5, Issues 3-4

Volume V, Issues 3-4 September 2011 PERSPECTIVES ON TERRORISM Volume 5, Issues 3-4 Special Double Issue on Terrorism and Political Violence in Africa Guest Editors: James J. F. Forest and Jennifer Giroux 2 September 2011 PERSPECTIVES ON TERRORISM Volume 5, Issues 3-4 Table of Contents: Articles Terrorism and Political Violence in Africa: Contemporary Trends in a Shifting Terrain ................................................................................................5 by James J.F. Forest and Jennifer Giroux Terrorism in Liberation Struggles: Interrogating the Engagement Tactics of the Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta ........................18 by Ibaba Samuel Ibaba ‘Forcing the Horse to Drink or Making it Realise its Thirst’? Understanding the Enactment of Anti-Terrorism Legislation (ATL) in Nigeria .............................................................................................................33 by Isaac Terwase Sampson and Freedom C. Onuoha Opportunity Costs or Costly Opportunities? The Arab Spring, Osama Bin Laden, and Al-Qaeda's African Affiliates .............................................50 by Alex S. Wilner Al-Qaeda's Influence in Sub-Saharan Africa: Myths, Realities and Possibilities .....................................................................................................63 by James J.F. Forest From Theory to Practice: Exploring the Organised Crime-Terror Nexus in Sub-Saharan Africa ...................................................................................81 by Annette -

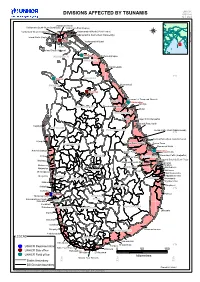

DIVISIONS AFFECTED by TSUNAMIS GIS Unit Sri Lanka

UNHCR DIVISIONS AFFECTED BY TSUNAMIS GIS Unit Sri Lanka ValikamamValikamam NorthNorth ValikamamValikamam South-WestSouth-West (Sandilipay)(Sandilipay) ValikamamValikamam EastEast (Kopay)(Kopay) Valikamam West (Chankanai) VadamaradchiVadamaradchi NorthNorth (Point(Point Perdro)Perdro) JAFFNAJAFFNA VadamaradchiVadamaradchi South-WestSouth-West (Karaveddy)(Karaveddy) Island North (Kayts) JaffnaJaffna VadamaradchiVadamaradchi EastEast Divisions.WOR Affected Jaffna DelftDelft DelftDelftIsland South (Velanai) KillinochchiKillinochchi KILINOCHCHIKILINOCHCHI KillinochchiKillinochchi PuthukudiyiruppuPuthukudiyiruppu MULLAITIVUMULLAITIVU MaritimepattuMaritimepattu 9°N MannarMannar VAVUNIYAVAVUNIYA MANNARMANNAR KuchchaveliKuchchaveli VavuniyaVavuniya TrincomaleeTrincomalee TownTown andand GravetsGravets MorawewaMorawewa TrincomaleeTrincomalee KinniyaKinniya ANURADHAPURAANURADHAPURA ThambalagamuwaThambalagamuwa MutturMuttur TRINCOMALEETRINCOMALEE SeruvilaSeruvila Verugal/Verugal/ EchchilampattaiEchchilampattai KoralaiKoralai PattuPattu NorthNorth KalpitiyaKalpitiya PUTTALAMPUTTALAM POLONNARUWAPOLONNARUWA KoralaiKoralai PattuPattu WestWest (Oddamavadi)(Oddamavadi) 8°N KoralaiKoralai PattuPattu WestWest (Valachchenai)(Valachchenai) MundelMundel KoralaiKoralai PattuPattu (South)(South) EravurEravur TownTown KURUNEGALAKURUNEGALA KoralaiKoralai PattuPattu (South)(South) EravurEravur TownTown ManmunaiManmunai NorthNorth ArachchikattuwaArachchikattuwa BatticaloaBatticaloa EravurEravur PattuPattu BatticaloaBatticaloaKattankudyKattankudy ManmunaiManmunai