Book Reviews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Social Doctrine of the Church Today

“Instaurare omnia in Christo” The Social Doctrine of the Church Today Christ, the King of the Economy Archbishop Lefebvre and Money Interview With Traditional Catholic Businessmen July - August 2016 It is not surprising that the Cross no longer triumphs, because sacrifice no longer triumphs. It is not surprising that men no longer think of anything but raising their standard of living, that they seek only money, riches, pleasures, comfort, and the easy ways of this world. They have lost the sense of sacrifice” (Archbishop Lefebvre, Jubilee Sermon, Nov. 1979). Milan — fresco from San Marco church, Jesus’ teaching on the duty to render to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s; and to God, the things that are God’s. Letter from the Publisher Dear readers, Because he is body and soul, man has basic human needs, like food, drink, clothes, and shelter, which he cannot obtain unless he has basic, minimal possessions. The trouble is that possessions quickly engender love for them; love breeds dependence; and depen- dence is only one step away from slavery. Merely human wisdom, like Virgil’s Aeneid, has stigmatized it as “the sacrilegious hunger for gold.” For the Catholic, the problem of material possessions is compounded with the issue of using the goods as if not using them, of living in the world without being of the world. This is the paradox best defined by Our Lord in the first beatitude: “Blessed be the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.” Our civilization is fast heading towards decomposition partly for not understanding these basic truths. -

Holy Land and Holy See

1 HOLY LAND AND HOLY SEE PAPAL POLICY ON PALESTINE DURING THE PONTIFICATES OF POPES PIUS X, BENEDICT XV AND PIUS XI FROM 1903 TO 1939 PhD Thesis Gareth Simon Graham Grainger University of Divinity Student ID: 200712888 26 July 2017 2 CONTENTS Chapter 1: Introduction – Question, Hypothesis and Methodology Chapter 2: A Saint for Jerusalem – Pope Pius X and Palestine Chapter 3: The Balfour Bombshell – Pope Benedict XV and Palestine Chapter 4: Uneasy Mandate – Pope Pius XI and Palestine Chapter 5: Aftermath and Conclusions Appendix 1.The Roads to the Holy Sepulchre – Papal Policy on Palestine from the Crusades to the Twentieth Century Appendix 2.The Origins and Evolution of Zionism and the Zionist Project Appendix 3.The Policies of the Principal Towards Palestine from 1903 to 1939 Appendix 4. Glossary Appendix 5. Dramatis Personae Bibliography 3 CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION – QUESTION, HYPOTHESIS AND METHODOLOGY 1.1. THE INTRIGUING QUESTION Invitation to Dr Theodor Herzl to attend Audience with Pope Pius X On 25 January 1904, the Feast of the Conversion of St Paul, the recently-elected Pope Pius X granted an Audience in the Vatican Palace to Dr Theodor Herzl, leader of the Zionist movement, and heard his plea for papal approval for the Zionist project for a Jewish national home in Palestine. Dr Herzl outlined to the Supreme Pontiff of the Catholic Church the full details of the Zionist project, providing assurances that the various Holy Places in Palestine would be “ex-territorialised” to ensure their security and protection, and sought the Pope’s endorsement and support, preferably through the issuing of a pro-Zionist encyclical. -

The Rite of Sodomy

The Rite of Sodomy volume iii i Books by Randy Engel Sex Education—The Final Plague The McHugh Chronicles— Who Betrayed the Prolife Movement? ii The Rite of Sodomy Homosexuality and the Roman Catholic Church volume iii AmChurch and the Homosexual Revolution Randy Engel NEW ENGEL PUBLISHING Export, Pennsylvania iii Copyright © 2012 by Randy Engel All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, New Engel Publishing, Box 356, Export, PA 15632 Library of Congress Control Number 2010916845 Includes complete index ISBN 978-0-9778601-7-3 NEW ENGEL PUBLISHING Box 356 Export, PA 15632 www.newengelpublishing.com iv Dedication To Monsignor Charles T. Moss 1930–2006 Beloved Pastor of St. Roch’s Parish Forever Our Lady’s Champion v vi INTRODUCTION Contents AmChurch and the Homosexual Revolution ............................................. 507 X AmChurch—Posing a Historic Framework .................... 509 1 Bishop Carroll and the Roots of the American Church .... 509 2 The Rise of Traditionalism ................................. 516 3 The Americanist Revolution Quietly Simmers ............ 519 4 Americanism in the Age of Gibbons ........................ 525 5 Pope Leo XIII—The Iron Fist in the Velvet Glove ......... 529 6 Pope Saint Pius X Attacks Modernism ..................... 534 7 Modernism Not Dead— Just Resting ...................... 538 XI The Bishops’ Bureaucracy and the Homosexual Revolution ... 549 1 National Catholic War Council—A Crack in the Dam ...... 549 2 Transition From Warfare to Welfare ........................ 551 3 Vatican II and the Shaping of AmChurch ................ 561 4 The Politics of the New Progressivism .................... 563 5 The Homosexual Colonization of the NCCB/USCC ....... -

Frederick Dent Grant and Ida Honore Grant Papers USGPL.FDGIHG

Frederick Dent Grant and Ida Honore Grant papers USGPL.FDGIHG This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on September 28, 2020. Mississippi State University Libraries P.O. Box 5408 Mississippi State 39762 [email protected] URL: http://library.msstate.edu/specialcollections Frederick Dent Grant and Ida Honore Grant papers USGPL.FDGIHG Table of Contents Summary Information ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical Note ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Scope and Content Note ...................................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................... 5 Controlled Access Headings ............................................................................................................................... 5 Related Collections ................................................................................................................................................ 6 Collection Inventory ............................................................................................................................................. 6 Series I: Correspondence ................................................................................................................................ -

Pontiff Asks Uthoiics to Assist Fellow

ENCYCUCAL TREATS NEEDS OF MISSIONS Supplement to the Denver Catholic Register N a t i o n a l N a t i o n a l PONTIFF ASKS UTHOIICS S e c t i o n THE S e c t i o n TO ASSIST FELLOW MAN REGISTER (Name Registered in the U. S. Patent Office) MIMtCR OF AUDIT tUNKAU OF CISCULATIONS Ay Migr. J*m*i I. T v c tk TU* Paper Is CotuMcM wltb NCWC WasbInftoB Nrss tMdqusrtsrt br Its Own Lssssd W lru U u Its tiwo John Leads Us to the Messias Vatican City,—Counsels for entrusting ^ a te r SperUI Ssrrtcs. RsIlfMus News Ssrvtcs, Mission Ssrvleos. Rsllflous Nsws Photos and NCWC Plcturo Sorvke responsibility to native Bishops and clergy in the Thursday, December 3, 1959 missions, for training native priests, and, for the first time in an encyclical, an appeal “to all those lay Catholics, wherever they might be, to come LAITY CHALLENGED TO SERVE forward in the professions and in public life to consider seriously the possibility of helping their brothers" are stressed in the fourth encyclical of Love in Action Vital Pope John XXIII’s Pontificate. Fntitled Princept Paxtomm For priests to be able to pen (The Prince of Sbepberda) and etrate the cultured classes, Pope dated Nov. 29, the document Jota instructed Bishops to pro mark! the 40th anniveraary of f i t “centers of culture In which For Aiding Missions 3 another great encyclical on the foreign missionaries and native miasions, Pope Benedict XV's priests may be able to put to Chicago. -

Reflections for Lent Year A

Church of Saint Leo the Great Lincroft, New Jersey Reflections for Lent Year A 1 Lenten Prayer Book composed by Reverend John T. Folchetti, D.Min. Pastor, Church of Saint Leo the Great Dedication His Holiness Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI Who taught us to see the Face of God in Christ Jesus the Eternal Son and His Eminence Timothy Michael Cardinal Dolan Archbishop of New York A Good Shepherd and dear friend 2 Introduction Lectio Divina Lectio Divina (Latin for Divine Reading) is a traditional monastic practice of Scriptural reading, meditation and prayer intended to promote communion with God and to increase the knowledge of God’s word. It does not treat Sacred Scripture as texts to be studied, but as God’s living word. Lectio, Meditatio, Oratio, Contemplatio Traditionally, Lectio Divina has four separate steps: a reading of a passage from Sacred Scripture, a reflection on its meaning, followed by prayer and contemplation on the Word of God. Historically, Lectio Divina has been a “community practice”, that is, performed by monks and nuns in monasteries but this practice can be used by an individual and any group, the family in particular. Lectio Divina has been likened to a meal. First, one takes a bite of the food (lectio). The food is then chewed (meditatio), its taste savored (oratio) and finally “digested” and made part of the body (contemplatio). The ultimate purpose of this form of meditative prayer is to lead one to a deeper knowledge of Jesus Christ, the Living Word of God, The Bread of Life. Preparation: Stillness It is very important that an atmosphere of calm and tranquility of mind and body be established before one begins the four traditional steps. -

4Th Sunday of Easter.Pdf

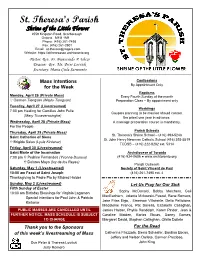

St. Theresa’s Parish Shrine of the Little Flower 2559 Kingston Road, Scarborough Ontario M1M 1M1 Phone: (416) 261-7498 Fax: (416) 261-2901 Email: [email protected] Website: https://sttheresassc.archtoronto.org Pastor: Rev. Fr. Bienvenido P. Ebcas Deacon: Rev. Mr. Peter Lovrick Secretary: Maria Ciela Sarmiento Confessions Mass Intentions By Appointment Only for the Week Baptisms Monday, April 26 (Private Mass) Every Fourth Sunday of the month Carmen Tiongson (Maylu Tiongson) Preparation Class – By appointment only Tuesday, April 27 (Livestreamed) Weddings 7:00 pm Healing for Camillus John Pulle Couples planning to be married should contact (Mary Tisseverasinghe) the priest one year in advance. Wednesday, April 28 (Private Mass) A marriage preparation course is mandatory. For the People Parish Schools Thursday, April 29 (Private Mass) St. Theresa’s Shrine School – (416) 393-5248 Saint Catherine of Siena St. John Henry Newman Catholic School (416) 393-5519 Brigida Salas (Lysle Kintanar) TCDSB – (416) 222-8282 ext. 5314 Friday, April 30 (Livestreamed) Saint Marie of the Incarnation Archdiocese of Toronto 7:00 pm Pedrine Fernandes (Yvonne Dsousa) (416) 934-0606 ● www.archtoronto.org Dolores Mayo (Ivy de los Reyes) Parish Outreach Saturday, May 1 (Livestreamed) Society of Saint Vincent de Paul 10:00 am Feast of Saint Joseph (416) 261-7498 ext. 4 Thanksgiving to Padre Pio by Mildred Halder Sunday, May 2 (Livestreamed) Let Us Pray for Our Sick Fifth Sunday of Easter Sophy McDonald, Bobby Melchers, Gail 10:00 am Birthday Blessings for Virginia Lagamon MacEachern, Jolanta Mirkowski-Paszel, Rene Romero, Special Intentions for Paul John & Patricia Jane Frias Eigo, , Emerson Villarante, Delio Pellicione, Kintanar Madeleine Franco, Pat Savella, Elizabeth Callaghan, PUBLIC MASSES ARE CANCELLED UNTIL James Halder, Phyllis Randolph, Karen Pinder, Jean & FURTHER NOTICE. -

Pope Benedict XVI - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Page 1 of 13

Pope Benedict XVI - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Page 1 of 13 Pope Benedict XVI From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. His Holiness Pope Benedict XVI (in Latin Benedictus XVI) Benedict XVI was born Joseph Alois Ratzinger on April 16, 1927. He is the 265th and current Pope, the bishop of Rome and head of the Roman Catholic Church. He was elected on April 19, 2005, in the 2005 papal conclave, over which he presided. He was formally inaugurated during the papal inauguration Mass on April 24, 2005. Contents 1 Overview 2 Early life (1927–1951) 2.1 Background and childhood (1927–1943) 2.2 Military service (1943–1945) 2.3 Education (1946–1951) 3 Early church career (1951–1981) 4 Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (1981 - 2005) 4.1 Health 4.2 Sex abuse scandal Name Joseph Alois Ratzinger 4.3 Dialogue with other faiths Papacy began April 19, 2005 5 Papacy 5.1 Election to the Papacy Papacy ended Incumbent 5.1.1 Prediction Predecessor Pope John Paul II 5.1.2 Election Successor Incumbent 5.2 Choice of name Born April 16, 1927 5.3 Early days of Papacy Place of birth Marktl am Inn, Bavaria, 6 See also Germany 7 Notes 8 Literature 9 Works 10 See also 11 External links and references 11.1 Official 11.2 Biographical 11.3 General Overview Pope Benedict was elected at the age of 78, the oldest pope since Clement XII (elected 1730) at the start of his papacy. He served longer as a cardinal before being elected pope than any pope since Benedict XIII (elected 1724). -

Catalog 191 PDF Download

Preserving Christian Publications, Inc. TRADITIONAL CATHOLIC BOOKS ____________________________________________ Offering More than 5,500 Used and Out-of-Print Catholic Titles Availiable in our Printed Catalogs and on Our Web Site www.pcpbooks.net And 46 Books in Print Selected from Catholic Classics & Important Books for Our Time Catalog 191 September 2021 Preserving Christian Publications, Inc. is a tax-exempt not-for-profit corporation devoted to the preservation of our Catholic heritage. All charitable contributions toward its used-book and publishing activities (not including payments for book purchases) are tax-deductible. The Liturgical Year by Abbot Prosper Guéranger The most famous classic commentary on the Masses throughout the Year. The Liturgical Year The Liturgical Year The Liturgical Year Advent Christmas Book 1 Christmas Book 2 The first three volumes of Dom Guéranger’s fifteen- Complete Advent/Christmas set $46 #5962 volume The Liturgical Year comprise Advent (vol. 1) and Advent: $16 #7026 Christmas (vols. 2 & 3). We are offering these three Christmas Bk. 1: $16 #7027 / Christmas Bk. 2: $16 #7028 volumes as a partial set, or as individual volumes that can Available: September 15, 2021 be purchased separately. All volumes are a sewn hardback edition. Volumes 4-6 (Septuagesima-Holy Week) available in November Used and Out-of-Print Titles OUR LORD / OUR LADY Problem of Jesus, The: A Free-Thinker's J., O.Cist 1950 200p dj (G) $17 #96220 Diary [using the literary device of a journal or Infant of Prague, The: The Story of the -

Our Lady of Victories Church (Serving Harrington Park, River Vale and the Pascack/Northern Valley) 150 Harriot Avenue, Harrington Park, New Jersey

Our Lady of Victories Church (serving Harrington Park, River Vale and the Pascack/Northern Valley) 150 Harriot Avenue, Harrington Park, New Jersey www.olvhp.org S˞˗ˍˊˢ, March 22, 2020 A.D. WELCOME 4th SUNDAY OF LENT To the Parish Family of OUR LADY OF VICTORIES (THE LITTLE CHURCH WITH THE BIG HEART) COME WORSHIP WITH US Rev. Wojciech B. Jaskowiak Pastor Mr. Thomas Lagatol Mr. Albert McLaughlin Deacons PARISH OFFICE Maria Hellrigel - Parish Secretary 201-768-1706 Religious Education (CCD) Susan Evanella Denise Coulter (LSEC) 201-768-1400 Sr. Elizabeth Holler, SC Sr. Mary Corrigan, SC In Residence-Convent Selena Piazza Elizabeth Gulfo Lesa Rossmann Martin Coyne II Ministers of Music Parish Trustees Jorden Pedersen Esq. Jon Fischer CFA President Parish Council Chairman Finance Committee THE SACRAMENT OF PENANCE/CONFESSION: Monday - Friday 7:30am - 7:50am. First Friday at 6:00pm - 6:50pm Special Masses: Saturday at 11:00a.m.-Noon; 3:00pm –3:40pm First Friday: 6:00pmConfessionsfollowed byDevotions & Mass First Saturday: 8:00am Mass of Immaculate Heart of Mary THE SACRAMENT OF BAPTISM: To register for Baptismal preparation and Baptism, First Saturday: 12:00pm Mass for Souls in Purgatory call the rectory. THE SACRAMENT OF CONFIRMATION: Novenas prayed after 8:00 a.m. Mass: Call the Religious Ed Office for requirements/class schedule. Our Lady of the Miraculous Medal: Monday THE SACRAMENT OF MATRIMONY: St. Jude and St. Anthony: Wednesday Please call the rectory for an appointment. Infant of Prague: 25th of the month 2THE SACRAMENT OF THE SICK/LAST RITES: Sick calls at any time in emergency. -

BLESSED BE GOD THIS IMMENSELY POPULAR CATHOLIC PRAYER BOOK Went Through Several Editions Between 1925 to 1961

Preserving Christian Publications, Inc. TRADITIONAL CATHOLIC BOOKS ____________________________________________ Offering More than 5,500 Used and Out-of-Print Catholic Titles Availiable in our Printed Catalogs and on Our Web Site www.pcpbooks.net And 34 Books in Print Selected from Catholic Classics & Important Books for Our Time Catalog 188 March 2020 Preserving Christian Publications, Inc. is a tax-exempt not-for-profit corporation devoted to the preservation of our Catholic heritage. All charitable contributions toward its used-book and publishing activities (not including payments for book purchases) are tax-deductible. DURABLE – ECONOMICAL BLESSED BE GOD THIS IMMENSELY POPULAR CATHOLIC PRAYER BOOK went through several editions between 1925 to 1961. We DOUAY-RHEIMS BIBLE have reprinted it five times, the last two of which have been as close as possible to its original specifications. This edition of our reprint INCLUDES such hi-quality features as a bonded leather flex cover, rounded IDEAL GIFT FOR STUDENTS corners, sewn binding, gilded page edges, a marking ribbon. ONLY $32.00 This ALL-TIME CLASSIC prayer book comes with prayers and devotions CHERISHED BY GENERATIONS OF CATHOLICS! Along with the usual array of morning and evening prayers, litanies, novenas, et cetera, also included Reprint of the are more rare devotions for Holy Days, Special Feasts, Holy Week, Ember and John Murphy Co. – P. J. Kenedy Week Days, Seasons and Months of the Year, and more. 1914 edition For EUCHARISTIC DEVOTION, an entire collection of prayers exists 1403 Pages / Bible Paper including a Holy Hour and the famous Forty Hours’ Adoration once practiced in every parish church! Sewn Hardcover This incredible POCKET-SIZE PRAYER BOOK also includes the Ordinary texts (in Latin and English), Sunday Epistles and Gospels (English only), Imitation Leather (Skivertex) Requiem and Nuptial Mass propers (in Latin and English) FOR THE TRADITIONAL LATIN MASS, and even Sunday Vespers and Benediction of Durable End Sheets (Permalex) the Blessed Sacrament. -

Spiritual Communion St. Thomas Aquinas Defined Spiritual

Spiritual Communion St. Thomas Aquinas defined Spiritual Communion as “an ardent desire to receive Jesus in the Holy Sacrament and a loving embrace as though we had already received Him.” The basis of this practice was explained by Pope St. John Paul II in his encyclical, Ecclesia de Eucharistia: ‘In the Eucharist, "unlike any other sacrament, the mystery [of Holy Communion] is so perfect that it brings us to the heights of every good thing: Here is the ultimate goal of every human desire, because here we attain God and God joins himself to us in the most perfect union." ‘Precisely for this reason it is good to cultivate in our hearts a constant desire for the sacrament of the Eucharist. This was the origin of the practice of "spiritual communion," which has happily been established in the Church for centuries and recommended by saints who were masters of the spiritual life. St. Teresa of Jesus wrote: "When you do not receive communion and you do not attend Mass, you can make a spiritual communion, which is a most beneficial practice; by it the love of God will be greatly impressed on you" [The Way of Perfection, Ch. 35] ‘Thus, the passionate desire for God, whom the saints have seen as the Sole Satisfier, and who in the Eucharist is the "summit and source of the Christian life", is at the root of this practice. The experience of St. Padre Pio illustrates the compelling desire felt by the saints in the face of the drawing and attracting power of God's love: “My heart feels as if it were being drawn by a superior force each morning just before uniting with Him in the Blessed Sacrament.