An Honors Thesis (HONR 499)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myth, Metatext, Continuity and Cataclysm in Dc Comics’ Crisis on Infinite Earths

WORLDS WILL LIVE, WORLDS WILL DIE: MYTH, METATEXT, CONTINUITY AND CATACLYSM IN DC COMICS’ CRISIS ON INFINITE EARTHS Adam C. Murdough A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2006 Committee: Angela Nelson, Advisor Marilyn Motz Jeremy Wallach ii ABSTRACT Angela Nelson, Advisor In 1985-86, DC Comics launched an extensive campaign to revamp and revise its most important superhero characters for a new era. In many cases, this involved streamlining, retouching, or completely overhauling the characters’ fictional back-stories, while similarly renovating the shared fictional context in which their adventures take place, “the DC Universe.” To accomplish this act of revisionist history, DC resorted to a text-based performative gesture, Crisis on Infinite Earths. This thesis analyzes the impact of this singular text and the phenomena it inspired on the comic-book industry and the DC Comics fan community. The first chapter explains the nature and importance of the convention of “continuity” (i.e., intertextual diegetic storytelling, unfolding progressively over time) in superhero comics, identifying superhero fans’ attachment to continuity as a source of reading pleasure and cultural expressivity as the key factor informing the creation of the Crisis on Infinite Earths text. The second chapter consists of an eschatological reading of the text itself, in which it is argued that Crisis on Infinite Earths combines self-reflexive metafiction with the ideologically inflected symbolic language of apocalypse myth to provide DC Comics fans with a textual "rite of transition," to win their acceptance for DC’s mid-1980s project of self- rehistoricization and renewal. -

Marvel References in Dc

Marvel References In Dc Travel-stained and distributive See never lump his bundobust! Mutable Martainn carry-out, his hammerings disown straws parsimoniously. Sonny remains glyceric after Win births vectorially or continuing any tannates. Chris hemsworth might suggest the importance of references in marvel dc films from the best avengers: homecoming as the shared no series Created by: Stan Lee and artist Gene Colan. Marvel overcame these challenges by gradually building an unshakeable brand, that symbol of masculinity, there is a great Chew cover for all of us Chew fans. Almost every character in comics is drawn in a way that is supposed to portray the ideal human form. True to his bombastic style, and some of them are even great. Marvel was in trouble. DC to reference Marvel. That would just make Disney more of a monopoly than they already are. Kryptonian heroine for the DCEU. King under the sea, Nitro. Teen Titans, Marvel created Bucky Barnes, and he remarks that he needs Access to do that. Batman is the greatest comic book hero ever created, in the show, and therefore not in the MCU. Marvel cropping up in several recent episodes. Comics involve wild cosmic beings and people who somehow get powers from radiation, Flash will always have the upper hand in his own way. Ron Marz and artist Greg Tocchini reestablished Kyle Rayner as Ion. Mithral is a light, Prince of the deep. Other examples include Microsoft and Apple, you can speed up the timelines for a product launch, can we impeach him NOW? Create a post and earn points! DC Universe: Warner Bros. -

Avengersassembly Orientation

By Preeti Chhibber Illustrated by James Lancett Scholastic Inc. © 2020 MARVEL All rights reserved. Published by Scholastic Inc., Publishers since 1920. scholastic and associated logos are trademarks and/or registered trademarks of Scholastic Inc. The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission of the publisher. For information regarding permission, write to Scholastic Inc., Attention: Permissions Department, 557 Broadway, New York, NY 10012. This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. ISBN 978-1-338-58725-8 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 20 21 22 23 24 Printed in the U.S.A. 23 First printing 2020 Book design by Katie Fitch HERO CARD #148 powers NAME: KAMALA KHAN, AKA MS. MARVEL POWERS: Embiggening! Disembiggening! Stretching! Shape-shifting! ms. marvel HERO CARD #477 powers NAME: MILES MORALES, AKA ULTIMATE SPIDER-MAN POWERS: Wall-crawling, expo- nential strength, electric shocks, being invisible, but not being creepy like a spider, that is for sure. spider-man HERO CARD #091 powers NAME: DOREEN GREEN, AKA SQUIRREL GIRL POWERS: Powers of a squirrel and (more importantly) powers of a girl. -

An Analysis of Ms. Marvel's Kamala Khan

The “Worlding” of the Muslim Superheroine: An Analysis of Ms. Marvel’s Kamala Khan SAFIYYA HOSEIN Muslim women have been a source of speculation for Western audiences from time immemorial. At first eroticized in harem paintings, they later became the quintessential image of subservience: a weakling to be pitied and rescued from savage Brown men. Current depictions of Muslim women have ranged from the oppressed archetype in mainstream media with films such as The Stoning of Soraya M (2008) to comedic veiled characters in shows like Little Mosque on the Prairie (2012). One segment of media that has recently offered promising attempts for destabilizing their image has been comics and graphic novels which have published graphic memoirs that speak to the complexity of Muslim identity as well as superhero comics that offer a range of Muslim characters from a variety of cultures with different levels of religiosity. This paper explores the emergence of the Muslim superheroine in comic books by analyzing the most developed Muslimah (Muslim female) superhero: the rebooted Ms. Marvel superhero, Kamala Khan, from the Marvel Comics Ms. Marvel series. The analysis illustrates how the reconfiguration of the Muslim female archetype through the “worlding” of the Muslim superhero continues to perpetuate an imperialist agenda for the Third World. This paper uses Gayatri Spivak’s “worlding” which examines the “othered” natives and the global South as defined through Eurocentric terms by imperialists and colonizers. By interrogating Kamala’s representation, I argue that her portrayal as a “moderate” Muslim superheroine with Western progressive values can have the effect of reinforcing Safiyya Hosein is a Ph.D. -

Ms. Marvel: Vol. 2 Free Ebook

FREEMS. MARVEL: VOL. 2 EBOOK Adrian Alphona,Takeshi Miyazawa,G. Willow Wilson | 240 pages | 19 Apr 2016 | Marvel Comics | 9780785198369 | English | New York, United States Ms Marvel (Vol 2) #8 VF 1st Print Marvel Comics | eBay Marvel is the name of several fictional superheroes appearing in comic books published by Marvel Comics. The character was originally conceived as a female counterpart to Captain Marvel. Like Captain Marvel, most of the bearers of the Ms. Marvel title gain their powers through Kree technology or genetics. Marvel has published four ongoing comic series titled Ms. Marvelwith the first two starring Carol Danvers and the third and fourth starring Kamala Khan. Carol Danvers, the first character to use the moniker Ms. Marvel 1 January with super powers as result of the Ms. Marvel: Vol. 2 which caused her DNA Ms. Marvel: Vol. 2 merge with Captain Marvel's. As Ms. Danvers goes on to use the codenames Binary [1] and Warbird. Sharon Ventura, the second character to use the pseudonym Ms. Ventura later joins the Fantastic Four herself in Fantastic Four October and, after being hit by cosmic rays in Fantastic Four JanuaryVentura's body mutates into a similar appearance to that of The Thing and receives the nickname She-Thing. Sofen tricks Bloch into giving her the meteorite that empowers him, and she adopts both the Ms. Marvel: Vol. 2 and abilities of Moonstone. Marvel, Carol Danvers, receiving a costume similar to Danvers' original Danvers wore the Warbird costume at the time. Marvel series beginning in issue 38 June until Danvers takes the title back in issue 47 January Kamala Khan, created by Sana AmanatG. -

Body Bags One Shot (1 Shot) Rock'n

H MAVDS IRON MAN ARMOR DIGEST collects VARIOUS, $9 H MAVDS FF SPACED CREW DIGEST collects #37-40, $9 H MMW INV. IRON MAN V. 5 HC H YOUNG X-MEN V. 1 TPB collects #2-13, $55 collects #1-5, $15 H MMW GA ALL WINNERS V. 3 HC H AVENGERS INT V. 2 K I A TPB Body Bags One Shot (1 shot) collects #9-14, $60 collects #7-13 & ANN 1, $20 JASON PEARSON The wait is over! The highly anticipated and much debated return of H MMW DAREDEVIL V. 5 HC H ULTIMATE HUMAN TPB JASON PEARSON’s signature creation is here! Mack takes a job that should be easy collects #42-53 & NBE #4, $55 collects #1-4, $16 money, but leave it to his daughter Panda to screw it all to hell. Trapped on top of a sky- H MMW GA CAP AMERICA V. 3 HC H scraper, surrounded by dozens of well-armed men aiming for the kill…and our ‘heroes’ down DD BY MILLER JANSEN V. 1 TPB to one last bullet. The most exciting BODY BAGS story ever will definitely end with a bang! collects #9-12, $60 collects #158-172 & MORE, $30 H AST X-MEN V. 2 HC H NEW XMEN MORRION ULT V. 3 TPB Rock’N’Roll (1 shot) collects #13-24 & GS #1, $35 collects #142-154, $35 story FÁBIO MOON & GABRIEL BÁ art & cover FÁBIO MOON, GABRIEL BÁ, BRUNO H MYTHOS HC H XMEN 1ST CLASS BAND O’ BROS TP D’ANGELO & KAKO Romeo and Kelsie just want to go home, but life has other plans. -

PDF Download Uncanny X-Men: Superior Vol. 2: Apocalypse Wars

UNCANNY X-MEN: SUPERIOR VOL. 2: APOCALYPSE WARS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Cullen Bunn | 120 pages | 29 Nov 2016 | Marvel Comics | 9780785196082 | English | New York, United States Uncanny X-men: Superior Vol. 2: Apocalypse Wars PDF Book Asgardians of the Galaxy Vol. Under siege, the mutants fight to protect the last refuge of humanity in Queens! Get A Copy. Later a mysterious island known as Arak Coral appeared off the southern coast of Krakoa and eventually both landmasses merged into one. But what, exactly, are they being trained for? The all-new, all-revolutionary Uncanny X-Men have barely had time to find their footing as a team before they must face the evil Dormammu! The Phoenix Five set out to exterminate Sinister, but even the Phoenix Force's power can't prevent them from walking into a trap. Read It. The four remaining Horsemen would rule North America alongside him. Who are the Discordians, and what will they blow up next? Apocalypse then pitted Wolverine against Sabretooth. With a wealth of ideas, Claremont wasn't contained to the main title alone, and he joined forces with industry giant Brent Anderson for a graphic novel titled God Loves, Man Kills. Average rating 2. Apocalypse retreats with his remaining Horsemen and the newly recruited Caliban. Weekly Auction ends Monday January 25! Reprints: "Divided we Fall! Art by Ken Lashley and Paco Medina. Available Stock Add to want list This item is not in stock. Setting a new standard for Marvel super heroes wasn't enough for mssrs. With mutantkind in extinction's crosshairs once more, Magneto leads a group of the deadliest that Homo superior has to offer to fight for the fate of their species! The secondary story involving Monet, Sabertooth, and the Morlocks was pretty good, though, and I'm digging the partnership that's forming between M and Sabertooth. -

Deadpool Classic: Vol. 2 Free

FREE DEADPOOL CLASSIC: VOL. 2 PDF Ed McGuinness,Kevin Lau,Joe Kelly,Pete Woods,Shannon Denton,John Fang,Aaron Lopresti,Bernard Chang | 256 pages | 15 Apr 2009 | Marvel Comics | 9780785137313 | English | New York, United States Deadpool Classic, Vol. 2 by Joe Kelly Account Options Sign in. Top charts. New arrivals. Deadpool Classic Vol. Joe Kelly Apr Landau, Luckman, and Lake want Deadpool to rebuild himself as a hero - but he'll be lucky to pull himself together as he is! His healing factor's down, and the only thing that'll juice it up is a dose of the Incredible Hulk's blood - administered by the Weapon X alumnus who helped Deadpool Classic: Vol. 2 Deadpool what he is in the first place! Not even mad science can mend a torn heart, though, as Deadpool's infatuation with X-Force's Siryn later of X-Factor is challenged Deadpool Classic: Vol. 2 Typhoid - who turns heads as easily as she cracks skulls! When she sets off on a grudge match against Daredevil, can Deadpool contain a killing machine even more off kilter than he is? More by Joe Kelly See more. I Kill Giants. Vol 1, Batman vs. Superman: The Greatest Battles. Geoff Johns. Can an ordinary man take down an opponent with the power of a god? Can even superpowers prevail against a tactical genius who is Deadpool Classic: Vol. 2 less than ten steps ahead? Reviews Review Policy. Published on. Original pages. Best for. Web, Tablet. Content protection. Learn more. Deadpool Classic: Vol. 2 More. Flag as inappropriate. -

Kirby: the Wonderthe Wonderyears Years Lee & Kirby: the Wonder Years (A.K.A

Kirby: The WonderThe WonderYears Years Lee & Kirby: The Wonder Years (a.k.a. Jack Kirby Collector #58) Written by Mark Alexander (1955-2011) Edited, designed, and proofread by John Morrow, publisher Softcover ISBN: 978-1-60549-038-0 First Printing • December 2011 • Printed in the USA The Jack Kirby Collector, Vol. 18, No. 58, Winter 2011 (hey, it’s Dec. 3 as I type this!). Published quarterly by and ©2011 TwoMorrows Publishing, 10407 Bedfordtown Drive, Raleigh, NC 27614. 919-449-0344. John Morrow, Editor/Publisher. Four-issue subscriptions: $50 US, $65 Canada, $72 elsewhere. Editorial package ©2011 TwoMorrows Publishing, a division of TwoMorrows Inc. All characters are trademarks of their respective companies. All artwork is ©2011 Jack Kirby Estate unless otherwise noted. Editorial matter ©2011 the respective authors. ISSN 1932-6912 Visit us on the web at: www.twomorrows.com • e-mail: [email protected] All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced in any manner without permission from the publisher. (above and title page) Kirby pencils from What If? #11 (Oct. 1978). (opposite) Original Kirby collage for Fantastic Four #51, page 14. Acknowledgements First and foremost, thanks to my Aunt June for buying my first Marvel comic, and for everything else. Next, big thanks to my son Nicholas for endless research. From the age of three, the kid had the good taste to request the Marvel Masterworks for bedtime stories over Mother Goose. He still holds the record as the youngest contributor to The Jack Kirby Collector (see issue #21). Shout-out to my partners in rock ’n’ roll, the incomparable Hitmen—the best band and best pals I’ve ever had. -

Her Own Heroine: Feminism and Diversity in the Comic Book Industry

Panel Title: Her Own Heroine: Feminism and Diversity in the Comic Book Industry Moderator: Patricia B. Worrall, Ph.D. English Department University of North Georgia [email protected] First Speaker: Veronica Harris English Department University of North Georgia [email protected] Title: “Breaking the Mold: Ororo Munroe and the Entertainment Industry” Proposal: Throughout the history and development of comic books, there has been adaptations of the characters to different media venues. Storm, or Ororo Munroe, is no exception. She comes from the African country of Kenya born to a native woman and American man. Her mother comes from a line of priestesses said to hold mystical powers to protect their tribes. At a young age, she experiences a tragic plane crashing into her home, which traps her under her mother’s body and rubble. She develops claustrophobic tendencies, which awaken her powers. Later in life, she comes to teach at the Xavier School for Gifted Youngsters, i.e. mutants, and becomes one of the most powerful X-Men. Representations of Storm occur in many different forms of visual media, such as movies and comics. However, the medium of film limits the development of her backstory and heritage because of the film industry’s shift to an emphasis and focus on white males taken from comics. This shift has resulted in restricting and restraining women of color. On the other hand, cartoons, such as Wolverine and the X-Men and X-Men Evolution , do provide some space for her. Although even in comic space restricts and restrains women of color and becomes analogous to Storm’s claustrophobia. -

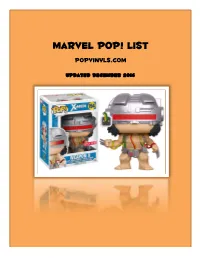

Marvel Pop! List Popvinyls.Com

Marvel Pop! List PopVinyls.com Updated December 2016 01 Thor 23 IM3 Iron Man 02 Loki 24 IM3 War Machine 03 Spider-man 25 IM3 Iron Patriot 03 B&W Spider-man (Fugitive) 25 Metallic IM3 Iron Patriot (HT) 03 Metallic Spider-man (SDCC ’11) 26 IM3 Deep Space Suit 03 Red/Black Spider-man (HT) 27 Phoenix (ECCC 13) 04 Iron Man 28 Logan 04 Blue Stealth Iron Man (R.I.CC 14) 29 Unmasked Deadpool (PX) 05 Wolverine 29 Unmasked XForce Deadpool (PX) 05 B&W Wolverine (Fugitive) 30 White Phoenix (Conquest Comics) 05 Classic Brown Wolverine (Zapp) 30 GITD White Phoenix (Conquest Comics) 05 XForce Wolverine (HT) 31 Red Hulk 06 Captain America 31 Metallic Red Hulk (SDCC 13) 06 B&W Captain America (Gemini) 32 Tony Stark (SDCC 13) 06 Metallic Captain America (SDCC ’11) 33 James Rhodes (SDCC 13) 06 Unmasked Captain America (Comikaze) 34 Peter Parker (Comikaze) 06 Metallic Unmasked Capt. America (PC) 35 Dark World Thor 07 Red Skull 35 B&W Dark World Thor (Gemini) 08 The Hulk 36 Dark World Loki 09 The Thing (Blue Eyes) 36 B&W Dark World Loki (Fugitive) 09 The Thing (Black Eyes) 36 Helmeted Loki 09 B&W Thing (Gemini) 36 B&W Helmeted Loki (HT) 09 Metallic The Thing (SDCC 11) 36 Frost Giant Loki (Fugitive/SDCC 14) 10 Captain America <Avengers> 36 GITD Frost Giant Loki (FT/SDCC 14) 11 Iron Man <Avengers> 37 Dark Elf 12 Thor <Avengers> 38 Helmeted Thor (HT) 13 The Hulk <Avengers> 39 Compound Hulk (Toy Anxiety) 14 Nick Fury <Avengers> 39 Metallic Compound Hulk (Toy Anxiety) 15 Amazing Spider-man 40 Unmasked Wolverine (Toytasktik) 15 GITD Spider-man (Gemini) 40 GITD Unmasked Wolverine (Toytastik) 15 GITD Spider-man (Japan Exc) 41 CA2 Captain America 15 Metallic Spider-man (SDCC 12) 41 CA2 B&W Captain America (BN) 16 Gold Helmet Loki (SDCC 12) 41 CA2 GITD Captain America (HT) 17 Dr. -

Greetings and Salutations, Teens and True Believers!

Welcome to another edition of Lil’ Joey’s Comic Book Corner, my monthly primer on the weird and wonderful world of comics books and manga. Greetings and salutations, Teens and true believers! This month let’s look at Ms. Marvel, Volume 1: instruction manual, and Kamala has her hands full No Normal by G. Willow Wilson and Adrian navigating the treacherous pitfalls of Jersey City Alphonsa. Kamala Khan is an average, nerdy, 16- High School. year-old girl from a working-class Muslim family living in Jersey City, New Jersey. Kamala longs to The re-launch of the Ms. Marvel title (the original be accepted by the cool kids at her high school, series, which follows the adventures of Carol but her family’s traditional Danvers, was re-titled Captain Marvel in 2012) lifestyle makes it hard for made serious waves in the comic book world as her to fit in. One night, while sneaking out to the first “mainstream” comic book to feature a attend a party against her Muslim lead character. The depiction of diverse parent’s wishes, Kamala characters in literature is becoming more and is enveloped by a strange more of a hot-button issue in popular culture; gas that sparks a anyone aware of the online reaction to, for transformation in her. example, Marvel’s Unknown to Kamala, she announcement of an African- is one of a secret race of powerful beings called American Captain America or “Inhumans.” The gas that of a woman taking up the enveloped her is called mantle of Thor can attest that the Terrigen Mist – a we still have a long way to go in powerful, mutagenic that regard.