Ann Symonds – Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Minutes of the Proceedings Legislative

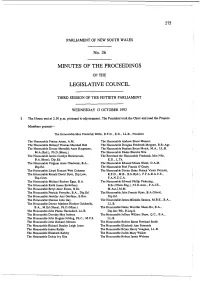

PARLIAMENT OF NEW SOUTH WALES No. 26 MINUTES OF THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL THIRD SESSION OF THE FIlTIETH PARLIAMENT WEDNESDAY 13 OCTOBER 1993 1 The House met at 2.30 p.m. pursuant to adjournment. The President took the Chair and read the Prayers. Members present- The Honourable Max Frederick Willis, R.F.D., E.D., LL.B., President The Honourable Franca Arena, A.M. The Honourable Andrew Bruce Manson The Honourable Richard Thomas Marshall Bull The Honourable Douglas Frederick Moppett, B.Sc.Agr. The Honourable Doctor Meredith Anne Burgmann, The Honourable Stephen Bruce Mutch. M.A.. LL.B. M.A.(Syd.). Ph.D.(Macq.) The Honourable Elaine Blanche Nile The Honourable Janice Carolyn Bumswoods. The Revcrend the Honourable Frederick John Nile, B.A.(Hons), Dip.Ed. E.D., L.Th. The Honourable Virginia Anne Chadwick, B.A.. The Honourable Edward Moses Obeid, O.A.M. Dip.Ed. The Honourable Paul Francis O'Grady The Honourable Lloyd Duncan Watt Coleman The Honourable Doctor Brian Patrick Victor Peuutti. The Honourable Ronald David Dyer. Dip.Law, R.F.D.. M.B.. B.S.(Syd.), F.F.A.R.A.C.S.. Dip.Crim. F.A.N.Z.C.A. The Honourable Michael Rueben Egan, B.A. The Honourable Edward Philip Pickering, The Honourable Keith James Enderbury B.Sc.(Chem.Ene.).- ,. F.I.E.Aus1.. F.A.I.E., The Honourable Beryl Alice Evans, B.Ec. M.Aus.1.M.M. The Honourable Patricia Forsythe. B.A., Dip.Ed. The Honourable John Francis Ryan, B.A.(Hons). The Honourable Jennifer Ann Gardiner, B.Bus. -

Copyright and Use of This Thesis This Thesis Must Be Used in Accordance with the Provisions of the Copyright Act 1968

COPYRIGHT AND USE OF THIS THESIS This thesis must be used in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Reproduction of material protected by copyright may be an infringement of copyright and copyright owners may be entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. Section 51 (2) of the Copyright Act permits an authorized officer of a university library or archives to provide a copy (by communication or otherwise) of an unpublished thesis kept in the library or archives, to a person who satisfies the authorized officer that he or she requires the reproduction for the purposes of research or study. The Copyright Act grants the creator of a work a number of moral rights, specifically the right of attribution, the right against false attribution and the right of integrity. You may infringe the author’s moral rights if you: - fail to acknowledge the author of this thesis if you quote sections from the work - attribute this thesis to another author - subject this thesis to derogatory treatment which may prejudice the author’s reputation For further information contact the University’s Director of Copyright Services sydney.edu.au/copyright ‘When the stars align’: decision-making in the NSW juvenile justice system 1990-2005 Elaine Fishwick A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Education and Social Work University of Sydney 2015 Faculty of Education and Social Work Office of Doctoral Studies AUTHOR’S DECLARATION This is to certify that: I. this thesis comprises only my original work towards the <insert Name of Degree> Degree II. -

Legislative Council

23 August, 1988 COUNCIL 22 1 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL Tuesday, 23 August, 1988 The President took the chair at 2.30 p.m. The President offered the Prayers. PETITIONS Education Policies The Hon. J. H. Jobling presented a petition requesting that the Minister for Education reconsi'der funding changes to class 4 schools and praying that this House consider the effect on teachers and on the standard of education of such funding changes within class 4 schools. Petition received. Abortion The Hon. Ann Symonds presented a petition supporting the continued availability of abortion and of counselling services at abortion clinics, and praying that this House vote against the private member's bill of Reverend the Hon. F. J. Nile. Petition received. GOVERNOR'S SPEECH: ADDRESS IN REPLY Third Day's Debate Debate resumed from 18th August. The Hon. JUDITH WALKER [2.38]: To continue my contribution to this debate I wish to refer to the significance of the report of the Commission of Audit. Not only is it the Holy Grail of the Greiner Government but also it fails to report the total assets of New South Wales. However, oversea reports reveal that, because of its assets and net worth, New South Wales has an AAA credit rating. The Greiner Government did not earn that rating, but the Wran Labor Government and the Unsworth Labor Government did. The Labor Party Opposition, in conjunction with the federal Labor Government, has created jobs and by instilling confidence in the business sector has created more jobs. Labor governments have introduced wage and dispute handling agreements and, in the main, the workers have accepted the agreements. -

Australia: Professor Marian Simms Head, Political Studies Department

Australia: Professor Marian Simms Head, Political Studies Department University of Otago Paper prepared for presentation at the joint ANU/UBA ‘John Fogarty Seminar’, Buenos Aires, Argentina 26-27 April 2007 Please note this paper is a draft version and is not for citation at this stage 1 Overview: Australian has been characterized variously as ‘The Lucky Country’ (Donald Horne), ‘A Small Rich Industrial Country’ (Heinz Arndt), and as suffering from ‘The Tyranny of Distance’ (Geoffrey Blainey). These distinguished authors have all mentioned negatives alongside positives; for example, political commentator Donald Horne’s famous comment was meant to be ironic – Australia’s affluence, and hence stability, were founded on good luck via rich mineral resources. For Blainey, the historian, geography mattered, both in terms of the vast distances from Europe and in terms of the vast size of the country.1 For economic historian Arndt, size was a double-edged sword – Australia had done well in spite of its small population. Those commentatories were all published in the 1970s. Since then much has happened globally, namely the stock market crash of the eighties, the collapse of communism in the late eighties and early nineties, the emergence of the Asian tigers in the nineties, and the attack on New York’s twin towers in 2001. All were profound events. It is the argument of this paper that in spite of these and other challenges, Australia’s institutional fabric has incorporated economic, social and political change. This is not to say that it has solved all of its social and economic problems, especially those dealing with minority groups such as the indigenous community, disaffected youth and some immigrant groups. -

Legislative Council

17803 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL Tuesday 22 September 2009 __________ The President (The Hon. Peter Thomas Primrose) took the chair at 2.30 p.m. The President read the Prayers. The PRESIDENT: I acknowledge the Gadigal clan of the Eora nation and its elders and thank them for their custodianship of this land. ASSENT TO BILLS Assent to the following bills reported: Aboriginal Land Rights Amendment Bill 2009 Births, Deaths and Marriages Registration Amendment (Change of Name) Bill 2009 NSW Lotteries (Authorised Transaction) Bill 2009 Occupational Licensing Legislation Amendment (Regulatory Reform) Bill 2009 Parliamentary Remuneration Amendment (Salary Packaging) Bill 2009 Crimes (Forensic Procedures) Amendment (Untested Registrable Persons) Bill 2009 CRIMES (FORENSIC PROCEDURES) AMENDMENT (UNTESTED REGISTRABLE PERSONS) BILL 2009 Message received from the Legislative Assembly returning the bill without amendment. DISTINGUISHED VISITORS The PRESIDENT: Order! I draw the attention of the House to the presence in the President's gallery and the public gallery of four former distinguished members: former President the Hon. Max Willis, former Leader of the Opposition the Hon. John Hannaford, the Hon. Patricia Forsythe and the Hon. John Ryan. DEATH OF THE HONOURABLE VIRGINIA ANNE CHADWICK, AO, A FORMER MEMBER OF THE LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL, A FORMER MINISTER OF THE CROWN AND A FORMER PRESIDENT OF THE LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL The PRESIDENT: I report the death on 18 September 2009 of the Hon. Virginia Anne Chadwick, aged 64 years, a former President and member of this House from 1978 to 1999. On behalf of the House I have extended to her family the deep sympathy of the Legislative Council in the loss sustained. -

Thesis August

Chapter 1 Introduction Section 1.1: ‘A fit place for women’? Section 1.2: Problems of sex, gender and parliament Section 1.3: Gender and the Parliament, 1995-1999 Section 1.4: Expectations on female MPs Section 1.5: Outline of the thesis Section 1.1: ‘A fit place for women’? The Sydney Morning Herald of 27 August 1925 reported the first speech given by a female Member of Parliament (hereafter MP) in New South Wales. In the Legislative Assembly on the previous day, Millicent Preston-Stanley, Nationalist Party Member for the Eastern Suburbs, created history. According to the Herald: ‘Miss Stanley proceeded to illumine the House with a few little shafts of humour. “For many years”, she said, “I have in this House looked down upon honourable members from above. And I have wondered how so many old women have managed to get here - not only to get here, but to stay here”. The Herald continued: ‘The House figuratively rocked with laughter. Miss Stanley hastened to explain herself. “I am referring”, she said amidst further laughter, “not to the physical age of the old gentlemen in question, but to their mental age, and to that obvious vacuity of mind which characterises the old gentlemen to whom I have referred”. Members obviously could not afford to manifest any deep sense of injury because of a woman’s banter. They laughed instead’. Preston-Stanley’s speech marks an important point in gender politics. It introduced female participation in the Twenty-seventh Parliament. It stands chronologically midway between the introduction of responsible government in the 1850s and the Fifty-first Parliament elected in March 1995. -

Kevin Rudd: a Professional Profile 59 the Queensland Office of the Cabinet 61 the Council of Australian Governments 69 Conclusion 77

The Entrepreneurial Bureaucrat A Study of Policy Entrepreneurship in the Formation of a National Strategy to Create an Asia-Literate Australia Christopher fames Mackenzie Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by research in Victoria University of Technology August 2001 .. 11 Contents .. Contents 11 . Declarations V1 .. Acknowledgements V11 Abstract Vlll . Abbreviations lX Introduction Policy Entrepreneurship and the NALSAS Strategy 1 Context of the Study 5 Microeconomic, Public Sector and Intergovernmental Reform in Australia 5 Engagement with Asia and the Significance of Asian Studies 8 Significance of the Study 10 Research Methodology 12 The Case Study 12 Interview Data and Documentary Evidence 13 Data Analysis 19 Summary of Methodology 21 Preview of the Organisation of the Study 21 Chapter One: Entrepreneurship in Policy Making: Theoretical Perspectives Introduction 24 Policy Entrepreneurs 27 Placing the Entrepreneur in a Theoretical Framework 32 Theories of Policy Entrepreneurship 39 Conclusion 52 Chapter Two: The Entrepreneur: Location and Context Introduction 57 111 Kevin Rudd: A Professional Profile 59 The Queensland Office of the Cabinet 61 The Council of Australian Governments 69 Conclusion 77 Chapter Three: The Development of Asian Studies in Australian Schools Introduction 78 Making Education Policy in Australia 79 The Teaching of Asian Languages in Australia 81 The Auchmuty Report 83 The Asian Studies Association of Australia (ASAA) 86 The National Policy on Languages 91 The Asian -

Robert Webster

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ORAL HISTORY PROJECT LC Members Ante-Room, Parliament House, Sydney Monday, 16 July 2018 The discussion commenced at 11.10 a.m. Present Mr David Blunt Dr David Clune Mr Robert Webster Monday, 16 July 2018 Legislative Council Page 1 Dr CLUNE: How did you become a member of Parliament? Mr WEBSTER: I became a farmer by accident. I was supposed to be a lawyer but being an only child of relatively elderly parents I started doing law at Sydney University in 1970 and not long after my father had a stroke. We only had a small farm with no farm hands and basically my dad said, "I can't pay someone to run the farm and keep you at university at the same time so you will have to come home and look after things until I get better." So I went back to the farm but he did not get better. I ended up doing a wool classing certificate instead of a law degree. But I was always interested in the law, in history and in English—which was my main subject at school—and it did not take long before I got interested in politics. The Whitlam Government was elected and did a lot of things which people in the country did not like so as a consequence I joined the then Country Party. I was elected to my first position, which was a director of the Carcoar Pastures Protection Board, in the early 1970s and I enjoyed it. My dad died when I was 21 so I took over full responsibility for the farm and my mother. -

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL Wednesday, 16 March

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL Wednesday, 16 March 1994 ______ The President (The Hon. Max Frederick Willis) took the chair at 2.30 p.m. The President offered the Prayers. PETITIONS Anti-Discrimination (Homosexual Vilification) Legislation Petitions praying that the anti-discrimination (homosexual vilification) legislation be repealed because it censors criticism of homosexuals, received from the Hon. Elaine Nile and Reverend the Hon. F. J. Nile. Container Deposit Legislation Petition praying that because of the detrimental effect of throw-away packaging on the environment, legislation be introduced imposing a mandatory deposit on all containers sold in New South Wales, received from the Hon. R. S. L. Jones. Serious Traffic Offence Penalties Petition praying that the House review the laws relating to road accident fatality or grievous bodily harm and institute severe penalties, received from the Hon. Judith Walker. Abortion Petition praying that because of community support for the continued availability of abortions and a woman's right to choose abortion and the continued availability of counselling services for abortion clinics, the House not support any restriction of existing abortion services, received from the Hon. Ann Symonds. GOVERNOR'S SPEECH: ADDRESS IN REPLY Sixth Day's Debate Debate resumed from 15 March. The Hon. DOROTHY ISAKSEN [2:37]: Since the Governor visited this House on 1 March the Government has announced his re-appointment for a further 12 months. I would like to take this opportunity to congratulate His Excellency on his re-appointment and to wish him and Mrs Shirley Sinclair a successful and rewarding 12 months. Without question, they are an extremely hard-working and enthusiastic partnership and give great support to many groups within our community. -

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL Friday, 1St November, 1991

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL Friday, 1st November, 1991 ______ The President took the chair at 9 a.m. The President offered the Prayers. PETITIONS Abortion Petition praying that because of recognition of the right to life of the unborn child, the House support the Procurement of Miscarriage Limitation Bill, received from the Hon. Dr Marlene Goldsmith. Stray Dogs Petition praying that the Premier fulfil his promise to ban the sending of stray dogs to laboratories within New South Wales, received from the Hon. R. S. L. Jones. BUDGET ESTIMATES AND RELATED PAPERS Financial Year 1991-92 Debate resumed from 30th October. The Hon. I. M. MACDONALD [9.5]: As I was saying in my truncated assessment of the Budget last Wednesday night, this Government has lost its credibility as an economic manager. It lost that primarily because, after spending $1 million whooping it up at the Regent Hotel, it released the Curran report. Though that report emphasised debt and liability, this Government brings forward a budget that will dramatically increase both the debt and the liability of this State. The State debt is $9 billion. The Hon. J. M. Samios: What is the debt of Victoria? The Hon. I. M. MACDONALD: The Hon. J. M. Samios refers to Victoria. I am happy to deal with that instantly. New South Wales taxation revenue per head of population is now $250 in excess of the average taxation level for an individual in Victoria. Yet members of this Government claim they are economic managers. The Government claims to be concerned about the level of debt in this State. -

The Hon. Max Frederick Willis) Took the Chair at 2.30 P.M

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL Wednesday, 15th September, 1993 ______ The President (The Hon. Max Frederick Willis) took the chair at 2.30 p.m. The President offered the Prayers. STANDING COMMITTEE ON STATE DEVELOPMENT Motion by the Hon. J. P. Hannaford agreed to: That the Hon. Beryl Evans be discharged from the Standing Committee on State Development and that the Hon. J. H. Jobling be appointed as a member of such Committee. JOINT SELECT COMMITTEE UPON WASTE MANAGEMENT Report The Hon. J. F. RYAN [2.35]: On behalf of the Chairman I desire to lay upon the table of the House the report of the Joint Select Committee upon Waste Management, dated September 1993. Ordered to be printed. The Hon. J. F. RYAN, by leave: In tabling this report I should like to thank all members of the committee for their efforts in bringing the report together. I am sure the Chairman in another place would appreciate my thanking on his behalf the members of this House who served on the committee and the staff who helped in the production of the report. Most members agreed with the recommendations contained in the report. It was well worth investigating the many serious issues and I am sure all members appreciated the unique process by which not only members of Parliament but also a series of reference groups worked together to produce the report. That successful experiment allowed the community to have some input. However, there were two matters with which I was not pleased. Important details of the report were revealed to the press before the document was tabled, and I understand that regrettable action is not in accordance with the normal procedures of this House. -

Minutes of Proceedings

1373 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL MINUTES OF PROCEEDINGS No. 116 TUESDAY 22 SEPTEMBER 2009 Contents 1 Meeting of the House ............................................................................................................................. 1374 2 Assents to Bills ....................................................................................................................................... 1374 3 Message from the Legislative Assembly—Crimes (Forensic Procedures) Amendment (Untested Registrable Persons) Bill 2009 ............................................................................................................... 1374 4 Distinguished Visitors ............................................................................................................................ 1374 5 Death of Former President—The Honourable Virginia Anne Chadwick AO ........................................ 1374 6 Condolence Motion—The Honourable Virginia Anne Chadwick AO .................................................. 1374 7 Ministerial Statement—Changes in Administration .............................................................................. 1375 8 Leadership—Government ...................................................................................................................... 1376 9 Ministerial Statement—Representation of Government in the Legislative Council .............................. 1376 10 Ministerial Statement—Parliamentary Secretaries ................................................................................