Download Sample

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Naupaka 032018

MARCH | APRIL 2018 RELAX, SHOP & PLAY AT WAIKOLOA BEACH RESORT E V E N T mar N W E apr S C A R L E N D A WaikoloaBeachResort.com Connected to the Past Keeping Hawaiian Traditions Alive Through Hula “To see through the fragments of time to the full power of the original being … that is a function of art.” —Mythologist Joseph Campbell n Hawai`i, art has often been a powerful vehicle connecting the Hawaiian people to their past Iand inspiring us all through its truth-telling and beauty. This is seen in the work of the state’s painters, wood carvers, sculptors, weavers, and more. And it is particularly apparent in the songs (mele), chants (oli), and hula dances that reach deep into the soul of the Manaola halau perfoming a hula kahiko at Merrie Monarch Festival in 2016. Photo courtesy of Merrie Monarch Festival. Hawaiian culture, both keeping its ancient traditions alive and telling its sacred stories. On a broader scale, hula is celebrated throughout the islands, At Waikoloa Beach Resort, guests and locals alike enjoy hula and in particular at the annual Merrie Monarch Festival held in Hilo performances several times a week on stages at both Queens’ (April 5 - 7, 2018). MarketPlace and Kings’ Shops, as well as at weekly lū`au at Hilton Waikoloa Village and Waikoloa Beach Marriott Resort & Spa. HULA TO THE WORLD “Respect for the Hawaiian culture was hard-baked from the Nani Lim-Yap is one of Hawai`i’s foremost practitioners of very beginning into everything we do,” says Scott Head, vice traditional dance, both as a dancer and as a kumu hula (master president resort operations. -

Nsn 09-14-16

IS BUGG • D AH “E Ala Na Moku Kai Liloloa” S F W R In This Issue: E E E N ! The Adornment of Ka‘ena E • Malia K. Evans R S Page 12 & 13 O I N H Waialua High School C S E Food For Thought H 1 Page 14 T 9 R 7 Menehune Surfing Championship O 0 N Entry Form Page 16 NORTH SHORE NEWS September 14, 2016 VOLUME 33, NUMBER 19 Cover Story & Photo by: Janine Bregulla St. Michael School Students Bless the North Shore Food Bank With a new school year upon the opportunity to teach a lesson distributed at the North Shore Food us, it is a challenge of every edu- that emphasizes the importance of Bank to those in need. Based upon cator to find ways to engage their community, they along with the a well-received response this will be students in activities that have the parents rose to the challenge. The an ongoing project throughout the power to become lifelong lessons. families, faculty and students col- school year that hopefully inspires So when the faculty of St. Mi- lected enough hygiene products to others. chael's School was presented with assemble 87 care packages that were PROUDLY PUBLISHED IN Permit No. 1479 No. Permit Hale‘iwa, Hawai‘i Honolulu, Hawaii Honolulu, U.S. POSTAGE PAID POSTAGE U.S. Home of STANDARD Hale‘iwa, HI 96712 HI Hale‘iwa, Menehune Surfing PRE-SORTED 66-437 Kamehameha Hwy., Suite 210 Suite Hwy., Kamehameha 66-437 Championships Page 2 www.northshorenews.com September 14, 2016 North Shore Neighborhood Board #27 Tuesday, September 27, 2016 7 p.m. -

Hawaiiana in 2002 a Bibliography of Titles of Historical Interest

Hawaiiana in 2002 A Bibliography of Titles of Historical Interest Compiled by Joan Hori, Jodie Mattos, and Dore Minatodani, assisted by Joni Watanabe Ahlo, Charles and Jerry Walker, with Rubellite Kawena Johnson. Kamehameha's Children Today. Honolulu: J. Walker, 2000. vi, 206 p. Genealogy. Alu Like, Inc. Native Hawaiian Population By District and Census Tract in Census 2000. Honolulu: Alu Like, Inc., 2001. iii, 85, 6 p. Blocker-Krantz, Lynn. To Honolulu in Five Days: Cruising Aboard Matson's S. S. Lurline. Berkeley, CA: Ten Speed Press, 2001. viii, 150 p. History of the Lurline and ocean travel to Hawai'i. Burlingame, Burl. Advance Force Pearl Harbor. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2002. 481 p. Businesses that built Hawaii. Honolulu: Honolulu Star-Bulletin, 2002. 88 p. Coleman, Stuart Holmes. Eddie Would Go: The Story of Eddie Aikau, Hawaiian Hero. Honolulu: MindRaising Press, 2001. 271 p. Cordy, Ross H. The Rise and Fall of the 0 'ahu Kingdom: A Brief Overview of O 'ahu 's History. Honolulu: Mutual Publishing, 2002. 64 p. Craig, Robert D. Historical Dictionary of Polynesia. 2nd ed. Lanham, MD: Scare- crow Press, 2002. xxxvi, 365 p. Includes Hawai'i. At Hamilton Library, University of Hawai'i at Manoa,Joan Hori is curator of the Hawai- ian Collection; Jodie Mattos is a librarian in the Business, Social Science and Humanities Department; Dore Minatodani is a librarian with the Hawaiian Collection; and Joni Wata- nabe is a student in the College of Business Administration. The Hawaiian Journal of History, vol. 37 (2003) 235 2^6 THE HAWAIIAN JOURNAL OF HISTORY Davis, Helen Kapililani Sanborn. -

Western-Constructed Narratives of Hawai'i

History in the Making Volume 11 Article 14 January 2018 Western-Constructed Narratives of Hawai’i Megan Medeiros CSUSB Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/history-in-the-making Part of the American Popular Culture Commons, Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons, History of the Pacific Islands Commons, and the Public History Commons Recommended Citation Medeiros, Megan (2018) "Western-Constructed Narratives of Hawai’i," History in the Making: Vol. 11 , Article 14. Available at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/history-in-the-making/vol11/iss1/14 This Public History is brought to you for free and open access by the History at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in History in the Making by an authorized editor of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Western-Constructed Narratives of Hawai’i By Megan Medeiros What comes to mind when you hear someone talking about Hawai’i? Perhaps, you envision an idyllic tropical locale filled with beautiful landscapes and sundrenched beaches just waiting to welcome you to a summer-time escape from reality? Or maybe you think of a secluded island, where play comes before work and people exude a carefree “aloha spirit”? In reality, Hawai’i is simultaneously neither and so much more. The widely held public conception of Hawai’i as a mystical tropical paradise is a misleading construction concocted by Westerners who possessed, at best, ephemeral and, at worst, completely fabricated conceptions of daily life within the Hawaiian Archipelago. How did this happen? How did such manifestly inaccurate representations of Hawai’i come to dominate popular perceptions of the islands and its people? The best way to understand this process is to apply the principles of “othering” put forth by renowned scholar Edward Said in his most famous work, Orientalism. -

M Narch Festival April 10 - 17, 1977 Hilo, Hawaii

~ERRI E M NARCH FESTIVAL APRIL 10 - 17, 1977 HILO, HAWAII . ,~.- Official Program & Guide It is my pleasure indeed to bid you welcome and send you the greetings of the people of the County 0 Hawaii on the occasi on of this 14th Annual Monarch Festiva l at Hi lo. We are especially happy to see that your field of p articipation includes groups from around the State of Hawaii as well as from other parts of o u r Nation. You are to be congratulated for the long hours and for the dedicated effort you-as dancers, m usi c ians, teachers, fam illes, and sponsors toget h er- have put in to o rganizing t h e p reparing yours Ives fo r th is special B ig Is land festiva l to share w ith residents and vis itors al ike. We are p leased also that o ur County of Hawaii fa cilitie s, as w ell as the beau tiful settings of o ur hotel s, will provide the backdrop for you I' contests and celebrat ions, and w e send YOLI our congratula tions and very best w is h es for a successful, safe and happy festival of th e pageantry, songs, dancing and MAYOR'S cultural activities so beautifully and so strongly rem iniscent of the spirit of old Hawaii. PROCLAMATION Kalakaua was a t raveler. In 1879, he becan1e t he first k ing to visi the Un ited States. In 1881, he was the fi rst k ing 0 f a wes ern, Christ ian nation to visit Japar . -

Lotus to Adjust Position and Center Spine Type Based on the Final Width of Spine

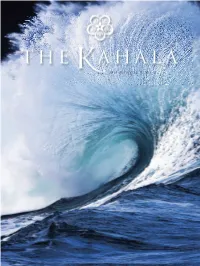

THE KAHALA Lotus to adjust position and center spine type based on the final width of spine. 2014-2015 VOL. 9, NO. 2 December 2014-june 2015, VOL. 9, NO.2 CONTENTS Volume 9, Number 2 Features 29 Layers of Meaning The abstract paintings of Honolulu-based artist Mary Mitsuda are a multilayered exploration of ideas, tracing lines of meaning and inviting the viewer to pause and look closer. Story by Christine Thomas Photography by Dana Edmunds 38 Journey Into Tranquility With its exquisite Japanese gardens, beautiful temple and impressive Amida Buddha, the Byodo-In shrine is a place for contemplation and introspection, in the lovely and serene Valley of the Temples on O‘ahu’s windward side. Story by Thelma Chang Lotus to adjust position and center spine type based on the final width of spine. 2014-2015 VOL. 9, NO. 2 46 The Eddie: The Ultimate Big-Wave Surfing Contest The Quiksilver in Memory of Eddie Aikau, one of the most prestigious competitions in surfi ng, is named for the ON THE COVER extraordinary man who inspired the phrase “Eddie Would Photographer Brian Go,” known to surfers around the world. Bielmann captures the wild and powerful Story by Stuart H. Coleman Photography by Brian Bielmann beauty of a wave on O‘ahu’s North Shore. 6 CONTENTS Volume 9, Number 2 10 Editor’s Note Depar tments PROFILES: 15 Miss Congeniality Senior Reservations Agent Lorna Barbosa Bennett Medeiros has greeted guests of The Kahala with her warm smile for nearly 40 years. Story by Simplicio Paragas Photography by Olivier Koning 21 INDULGENCES: Art of Zen Yoga can be experienced in many ways at The Kahala, from atop a standup AD paddleboard, in the pool or in the hotel’s fitness center. -

1856 1877 1881 1888 1894 1900 1918 1932 Box 1-1 JOHANN FRIEDRICH HACKFELD

M-307 JOHANNFRIEDRICH HACKFELD (1856- 1932) 1856 Bornin Germany; educated there and served in German Anny. 1877 Came to Hawaii, worked in uncle's business, H. Hackfeld & Company. 1881 Became partnerin company, alongwith Paul Isenberg andH. F. Glade. 1888 Visited in Germany; marriedJulia Berkenbusch; returnedto Hawaii. 1894 H.F. Glade leftcompany; J. F. Hackfeld and Paul Isenberg became sole ownersofH. Hackfeld& Company. 1900 Moved to Germany tolive due to Mrs. Hackfeld's health. Thereafter divided his time betweenGermany and Hawaii. After 1914, he visited Honolulu only threeor fourtimes. 1918 Assets and properties ofH. Hackfeld & Company seized by U.S. Governmentunder Alien PropertyAct. Varioussuits brought againstU. S. Governmentfor restitution. 1932 August 27, J. F. Hackfeld died, Bremen, Germany. Box 1-1 United States AttorneyGeneral Opinion No. 67, February 17, 1941. Executors ofJ. F. Hackfeld'sestate brought suit against the U. S. Governmentfor larger payment than was originallyallowed in restitution forHawaiian sugar properties expropriated in 1918 by Alien Property Act authority. This document is the opinion of Circuit Judge Swan in The U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals forthe Second Circuit, February 17, 1941. M-244 HAEHAW All (BARK) Box 1-1 Shipping articleson a whaling cruise, 1864 - 1865 Hawaiian shipping articles forBark Hae Hawaii, JohnHeppingstone, master, on a whaling cruise, December 19, 1864, until :the fall of 1865". M-305 HAIKUFRUIT AND PACKlNGCOMP ANY 1903 Haiku Fruitand Packing Company incorporated. 1904 Canneryand can making plant installed; initial pack was 1,400 cases. 1911 Bought out Pukalani Dairy and Pineapple Co (founded1907 at Pauwela) 1912 Hawaiian Pineapple Company bought controlof Haiku F & P Company 1918 Controlof Haiku F & P Company bought fromHawaiian Pineapple Company by hui of Maui men, headed by H. -

Hawaiian Lifeguard Association Watch Collection It Could Be Said That Hawaii Holds the Key to World Peace

TIME IS EVERYTHING OFFICIAL WATCH The Hawaiian Lifeguard Association watch collection It could be said that Hawaii holds the key to world peace ... it’s called the spirit of was created to serve the aloha, which encompasses the charm, warmth, and sincerity of the Hawaiian people. needs of these lifeguards on Aloha is more than a word of greeting or farewell or a salutation. Aloha means a mutual regard and the job, and launches just as affection and extends warmth in caring with no obligation in return. Aloha is the essence of relationships the organization is celebrating in which each person is important to every other person for collective existence. Aloha means to hear what is not said, to see what cannot be seen, and to know the unknowable. its 100th Anniversary. The watches are made to stand up to the The aloha spirit of Hawaii is alive and well in the work done by the Hawaiian Lifeguard enormous power of the ocean, but are also Association in their daily efforts to ensure the safety of those in the ocean. excellent knock-around watches, suitable for most any water environment, whether in Hawaii’s big waves or less challenging situations. Plus, they’re just cool looking casual lifestyle timepieces, perfect for everyday wear. The HLA watches are made with 316L stainless steel cases and bezels, 120 click unidirectional ratcheting bezels for diving, screw in case backs and crown to ensure 200 meters water resistance. In addition, the watches have extremely reliable Japanese quartz movements, Official HLA highly scratch resistant K1 glass crystals, and OFFICIAL WATCH OF THe 5508 comfortable genuine NBR rubber straps with HAWAIIAN LIFEGUARD ASSOCIATION patterned back for ventilation. -

Notable Hawaiians of the 20Th Century

Notable Hawaiians of the 20th Century Notable Hawaiians • Notable Hawaiians Hawaiians • Notable Hawaiians • Notable Hawaiians When the second issue of ‘Öiwi: A Native newspaper and magazine articles, television Hawaiian Journal was being conceptualized news reports, and an occasional book profile in 1999, it was difficult to ignore the highlighted a few Hawaiians now and then, number of “best of” lists which were being no one had taken account at any length of announced on almost a daily basis. It seemed Hawaiians who were admired by and who as if we couldn’t get enough—What were inspired other Hawaiians. the most important books of the millennium? The one hundred most significant events? We began discussing this idea amongst The best and worst dressed movie stars? ourselves: Whom did we consider noteworthy While sometimes humorous, thought- and important? Whom were we inspired by provoking, and/or controversial, the in our personal, spiritual, and professional categories were also nearly endless. Yet all lives? These conversations were enthusiastic the hoopla was difficult to ignore. After all, and spirited. Yet something was missing. there was one question not being addressed What was it? Oh yes—the voice of the in the general media at both the local and people. We decided that instead of imposing national levels: Who were the most notable our own ideas of who was inspirational and Hawaiians of the 20th century? After all the noteworthy, we would ask the Hawaiian attention given over the years to issues of community: “Who do you, the -

ASIA PACIFIC DANCE FESTIVAL Stories

2015 ASIA PACIFIC DANCE FESTIVAL Stories LIVING THE ART OF HULA THURSDAY, JULY 16, 2015 • 7:30PM John F. Kennedy Theatre, University of Hawai‘i at Ma¯ noa LOCAL MOTION! SUNDAY, JULY 19, 2015 • 2:00PM John F. Kennedy Theatre, University of Hawai‘i at Ma¯ noa CHURASA – OKINAWAN DRUM & DANCE THURSDAY, JULY 23, 2015 • 7:30PM John F. Kennedy Theatre, University of Hawai‘i at Ma¯ noa WELCOMING CEREMONY FRIDAY, JULY 24, 2015 • 6:00PM East-West Center Friendship Circle STORIES I SATURDAY, JULY 25, 2015 • 7:30PM John F. Kennedy Theatre, University of Hawai‘i at Ma¯ noa STORIES II SUNDAY, JULY 26, 2015 • 2:00PM John F. Kennedy Theatre, University of Hawai‘i at Ma¯ noa HUMANITIES FORUM SUNDAY, JULY 26, 2015 • 4:45PM East-West Center Imin Center, Jefferson Hall A co-production of the University of Hawai‘i at Ma¯ noa Outreach College and East-West Center Arts Program with the support of the University of Hawai‘i at Ma¯ noa Department of Theatre and Dance. 2015 ASIA PACIFIC DANCE FESTIVAL ASIA PACIFIC DANCE FESTIVAL Director Tim Slaughter Associate Director Eric Chang Organizing Committee William Feltz Kara Miller Michael Pili Pang Amy Lynn Schiffner Yukie Shiroma Judy Van Zile Staff Margret Arakaki, Assistant to Director; Kay Linen, Grant Writer Production Staff M Richard, Production Coordinator; Camille Monson and Anna Reynolds, Festival Assistants; Justin Fragiao, Site Manager; Vince Liem, Lighting Designer; Todd Bodden, Sound Engineer; Samuel Bukoski and Maggie Songer, Production Crew; Stephanie Jones, Costume Crew; Margret Arakaki, Box Office Supervisor; -

Hula: Kalākaua Breaks Cultural Barriers

Reviving the Hula: Kalākaua Breaks Cultural Barriers Breaking Barriers to Return to Barrier to Cultural Tradition Legacy of Tradition Tradition Kalākaua Promotes Hula at His Thesis Tourism Thrives on Hula Shows In 1830, Queen Kaʻahumanu was convinced by western missionaries to forbid public performances of hula Coronation Hula became one of the staples of Hawaiian tourism. In the islands, tourists were drawn to Waikiki for the which led to barriers that limited the traditional practice. Although hula significantly declined, King Kalākaua David Kalākaua became king in 1874 and at his coronation on February 12, 1883 he invited several hālau (hula performances, including the famed Kodak Hula Show in 1937. broke cultural barriers by promoting public performances again. As a result of Kalākaua’s promotion of hula, schools) to perform. Kalākaua’s endorsement of hula broke the barrier by revitalizing traditional practices. its significance remains deeply embedded within modern Hawaiian society. “The orientation of the territorial economy was shifting from agribusiness to new crops of tourists...Hawaiian culture- particularly Hawaiian music and hula-became valued commodities… highly politicized, for whoever brokered the presentation of Hawaiian culture would determine the development of tourism in Hawaii.” “His Coronation in 1883 and jubilee “The coronation ceremony took place at the newly Imada, Adria. American Quarterly, vol. 56, no. 1, Mar. 2004 celebration in 1886 both featured hula rebuilt Iolani Palace on February 12, 1883. The festivities then continued for two weeks thereafter, concluding performances.” “In 1937, Fritz Herman founded the Kodak Hula Show, a performance venue feasts hosted by the king for the people and nightly "History of Hula." Ka `Imi Na'auao O Hawaii Nei Institute. -

A Brief History of the Hawaiian People

0 A BRIEF HISTORY OP 'Ill& HAWAIIAN PEOPLE ff W. D. ALEXANDER PUBLISHED BY ORDER OF THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE HAWAIIAN KINGDOM NEW YORK,: . CINCINNATI•:• CHICAGO AMERICAN BOOK C.OMPANY Digitized by Google ' .. HARVARD COLLEGELIBRAllY BEQUESTOF RCLANOBUr.ll,' , ,E DIXOII f,'.AY 19, 1936 0oPYBIGRT, 1891, BY AlilBIOAN BooK Co)[PA.NY. W. P. 2 1 Digit zed by Google \ PREFACE AT the request of the Board of Education, I have .fi. endeavored to write a simple and concise history of the Hawaiian people, which, it is hoped, may be useful to the teachers and higher classes in our schools. As there is, however, no book in existence that covers the whole ground, and as the earlier histories are entirely out of print, it has been deemed best to prepare not merely a school-book, but a history for the benefit of the general public. This book has been written in the intervals of a labo rious occupation, from the stand-point of a patriotic Hawaiian, for the young people of this country rather than for foreign readers. This fact will account for its local coloring, and for the prominence given to certain topics of local interest. Especial pains have been taken to supply the want of a correct account of the ancient civil polity and religion of the Hawaiian race. This history is not merely a compilation. It is based upon a careful study of the original authorities, the writer having had the use of the principal existing collections of Hawaiian manuscripts, and having examined the early archives of the government, as well as nearly all the existing materials in print.