Salsa on St. Clair

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neighbourhood Equity Scores for Toronto Neighbourhoods and Recommended Neighbourhood Improvement Areas

Appendix B Neighbourhood Equity Scores for Toronto Neighbourhoods and Recommended Neighbourhood Improvement Areas All Scores are out of a maximum 100 points: the lower the Score, the higher the level of total overall inequities faced by the neighbourhood. Neighbourhoods with Scores lower than the Neighbourhood Equity Benchmark of 42.89 face serious inequities that require immediate action. Neighbourhoods marked with "*" in the Rank column were designated by Council as Priority Neighbourhood Areas for Investment (PNIs) under the 2005 Strategy. For neighbourhoods marked with a "+" in the Rank column, a smaller portion of the neighbourhood was included in a larger Priority Neighbourhood Areas for Investment designated by Council under the 2005 Strategy. Neighbourhood Recommended Rank Neighbourhood Number and Name Equity Score as NIA 1* 24 Black Creek 21.38 Y 2* 25 Glenfield-Jane Heights 24.39 Y 3* 115 Mount Dennis 26.39 Y 4 112 Beechborough-Greenbrook 26.54 Y 5 121 Oakridge 28.57 Y 6* 2 Mount Olive-Silverstone-Jamestown 29.29 Y 7 5 Elms-Old Rexdale 29.54 Y 8 72 Regent Park 29.81 Y 9 55 Thorncliffe Park 33.09 Y 10 85 South Parkdale 33.10 Y 11* 61 Crescent Town 33.21 Y 12 111 Rockcliffe-Smythe 33.86 Y 13* 139 Scarborough Village 33.94 Y 14* 21 Humber Summit 34.30 Y 15 28 Rustic 35.40 Y 16 125 Ionview 35.73 Y 17* 44 Flemingdon Park 35.81 Y 18* 113 Weston 35.99 Y 19* 22 Humbermede 36.09 Y 20* 138 Eglinton East 36.28 Y 21 135 Morningside 36.89 Y Staff report for action on the Toronto Strong Neighbourhoods Strategy 2020 1 Neighbourhood Recommended -

City of Toronto — Detached Homes Average Price by Percentage Increase: January to June 2016

City of Toronto — Detached Homes Average price by percentage increase: January to June 2016 C06 – $1,282,135 C14 – $2,018,060 1,624,017 C15 698,807 $1,649,510 972,204 869,656 754,043 630,542 672,659 1,968,769 1,821,777 781,811 816,344 3,412,579 763,874 $691,205 668,229 1,758,205 $1,698,897 812,608 *C02 $2,122,558 1,229,047 $890,879 1,149,451 1,408,198 *C01 1,085,243 1,262,133 1,116,339 $1,423,843 E06 788,941 803,251 Less than 10% 10% - 19.9% 20% & Above * 1,716,792 * 2,869,584 * 1,775,091 *W01 13.0% *C01 17.9% E01 12.9% W02 13.1% *C02 15.2% E02 20.0% W03 18.7% C03 13.6% E03 15.2% W04 19.9% C04 13.8% E04 13.5% W05 18.3% C06 26.9% E05 18.7% W06 11.1% C07 29.2% E06 8.9% W07 18.0% *C08 29.2% E07 10.4% W08 10.9% *C09 11.4% E08 7.7% W09 6.1% *C10 25.9% E09 16.2% W10 18.2% *C11 7.9% E10 20.1% C12 18.2% E11 12.4% C13 36.4% C14 26.4% C15 31.8% Compared to January to June 2015 Source: RE/MAX Hallmark, Toronto Real Estate Board Market Watch *Districts that recorded less than 100 sales were discounted to prevent the reporting of statistical anomalies R City of Toronto — Neighbourhoods by TREB District WEST W01 High Park, South Parkdale, Swansea, Roncesvalles Village W02 Bloor West Village, Baby Point, The Junction, High Park North W05 W03 Keelesdale, Eglinton West, Rockcliffe-Smythe, Weston-Pellam Park, Corso Italia W10 W04 York, Glen Park, Amesbury (Brookhaven), Pelmo Park – Humberlea, Weston, Fairbank (Briar Hill-Belgravia), Maple Leaf, Mount Dennis W05 Downsview, Humber Summit, Humbermede (Emery), Jane and Finch W09 W04 (Black Creek/Glenfield-Jane -

Community Check-Up: Downsview-Roding-Cfb Get to Know North York! | NORTH YORK MIRROR W |

9 community check-up: downsview-roding-cfb get to know north york! YORK MIRROR w | | NORTH As part of a Summer 020304050607080910 07080910 Snapshot feature, 2001 2011 2006 2011 The North York Mirror looks at the COMMUNITY DIFFERENCE FIVE-YEAR changing trends and demographics in of a decade change its local neighbour- check-up hoods. Data courtesy This week: Downsview-Roding-CFB August 27, 2013 Tuesday, Statistics Canada via the City of Toronto. >3x -21.9% Downsview-Roding- Between 2001 and 2011, the number While Italian remains the top CFB: Population Allen Road and Sheppard Avenue of people in Downsview-Roding-CFB non-official Home Language in the (2011): 34,655 West. who listed Tagalog as their Home neighbourhood the number of people Language more than tripled (295 in Downsview-Roding-CFB who people to 895). listed Italian as their Home Language LANGUAGES dropped by 21.9 per cent between 2006 and 2011. Italian is the most common non- official language in Downsview- Roding-CFB. In the 2011 census, 14.6 -6.7% per cent of residents listed Italian CITY While the number of people in the +51.8% as their Mother Tongue, and 8.4 per 0-14 age group (Children) has grown LIVING ARRANGEMENTS cent listed Italian as their Home between 2006 to 2011, the group’s The number of people in Downsview- CONTEXT FOR SENIORS (age 65+) Language. overall population is still down 6.7 Roding-CFB who listed Portuguese In the 2011 census, the percentage of A comparison of a per cent from its 2001 total. -

The North York East LIP Strategic Plan and Report

The North York East LIP Strategic Plan and Report The North York East Strategic Plan has been developed around six areas of focus: Information & Outreach; Civic Engagement; Collaboration & Capacity Building; Language Training & Supports; Labour Market; and Health Services.Six working groups will be established to address these areas of focus. In- depth directions for each working group are outlined in the main body of this report Executive Summary In 2009, Citizenship and Immigration Canada (CIC), in partnership with the Ontario Ministry of Citizenship and Immigration, launched Local Immigration Partnership (LIP) projects throughout Ontario. LIPs were developed as research initiatives to identify ways to coordinate and enhance local service delivery to newcomers across the province, while promoting efficient use of resources. In October 2009, Working Women Community Centre entered an agreement with CIC to lead a LIP project in the North York East area of Toronto. The North York East LIP is located in the far north of the city, contained by Steeles Avenue to the north, Highway 401 to the south, Victoria Avenue East to the east and the Don Valley River to the west. The area population is almost 80,000, 70% of which are immigrants to Canada. A major priority for the North York East LIP project was to root its research in the real-life experiences of local newcomers and local community organizations. In total, over 400 newcomers & immigrants, and over 100 service providers were consulted and engaged with to identify challenges, solutions and new directions for the settlement sector in the area. Methods of engagement for both newcomers and service providers included focus group research, key-informant interviews, community consultations and advisory panel workshops. -

Cycling Service by Neighbourhood

CITY OF CITY OF VAUGHAN MARKHAM ± 116 130 21 24 36 50 49 48 2 35 27 37 117 129 CITY OF 22 34 47 46 131 3 25 51 52 PICKERING 132 1 4 38 53 118 128 5 40 26 33 134 23 45 135 39 6 28 29 105 126 113 127 137 31 32 41 42 119 133 8 30 103 7 136 115 112 108 102 43 125 138 100 140 110 109 104 99 44 11 10 9 107 106 101 55 139 111 56 124 54 120 91 92 123 13 90 94 96 97 58 15 114 98 57 93 59 60 12 89 88 95 61 67 66 121 14 83 74 80 79 68 69 62 122 16 87 71 64 84 81 65 86 78 75 72 73 63 85 76 17 82 70 20 CITY OF 77 LAKE 18 MISSISSAUGA 19 ONTARIO 0 3 6 12 Km Legend Notes: KM of Cycling Infrastructure by KM of Cycling Service By Neighbourhood Streets per Neighbourhood 1 - Cycling Service is the proportion of street kilometres in the neighbourhood (excluding highways) Transportation Services Cycling Infrastructure & Programs Unit 0.0% - 2.4% that have cycling routes (cycle tracks, bike lanes, trails, quiet street sharrows), represented as a percentage Data Source: Contains information licensed under 2.5% - 4.5% (out of 100). The more cycling routes that exist, the higher the score. the Open Government License – Toronto 2 - Neighbourhood Equity Index Scores (out of 100) are those identified by City of Toronto Social Development, Projection: NAD 1927 MTM 3 4.6% - 6.9% Finance & Administration Division for the Toronto Strong Neighbourhoods Strategy 2020. -

Low Other* Dwelling Density Availability of Destinations

21 24 116 130 2 35 36 50 49 48 27 131 22 34 37 117 129 3 25 51 52 47 46 4 132 26 38 53 118 1 5 33 40 128 135 134 23 39 45 6 29 113 28 32 105 133 31 41 42 119 126 137 7 8 30 103 127 136 115 112 108 102 43 125 100 138 140 11 10 110 109 101 99 44 9 111 107 104 56 55 139 106 124 Dwelling Availability of 91 92 97 54 120 density destinations 13 90 94 96 58 123 15 89 98 57 High - High 12 114 93 59 60 14 88 95 67 61 121 83 74 66 High - Low 87 80 79 71 68 69 62 16 75 64 122 86 84 81 78 76 65 Low - High 7372 63 85 70 Low - Low 20 17 82 77 Other* 18 19 0 2.5 5 km * Indicates DB belonged to the middle quintile of Neighbourhoods dwelling density and/or availability of destinations 1 West Humber-Clairville 25 Glenfield-Jane Heights 49 Bayview Woods-Steeles 73 Moss Park 96 Casa Loma 121 Oakridge 2 Mount Olive-Silverstone- 26 Downsview-Roding-CFB 50 Newtonbrook East 74 North St. James Town 97 Yonge-St.Clair 122 Birchcliffe-Cliffside Jamestown 27 York University Heights 51 Willowdale East 75 Church-Yonge Corridor 98 Rosedale-Moore Park 123 Cliffcrest 3 Thistletown-Beaumond Heights 28 Rustic 52 Bayview Village 76 Bay Street Corridor 99 Mount Pleasant East 124 Kennedy Park 4 Rexdale-Kipling 29 Maple Leaf 53 Henry Farm 77 Waterfront Communities- 100 Yonge-Eglinton 125 Ionview 5 Elms-Old Rexdale 30 Brookhaven-Amesbury 54 O'Connor-Parkview The Island 101 Forest Hill South 126 Dorset Park 6 Kingsview Village-The Westway 31 Yorkdale-Glen Park 55 Thorncliffe Park 78 Kensington-Chinatown 102 Forest Hill North 127 Bendale 7 Willowridge-Martingrove-Richview 32 Englemount-Lawrence -

Community Check-Up: Hillcrest Village Russian Spanish Persian Korean Cantonese - Hillcrest Village: Population (2011): 17,650 Their Homelanguage

8 | community check-up: hillcrest village get to know north york! The North York 020304050607080910 07080910 Mirror looks at the 2001 2011 2006 2011 changing trends and demographics in COMMUNITY DIFFERENCE FIVE-YEAR its local neighbour- hoods. Data courtesy of a decade change Statistics Canada via check-up Tuesday, September 3, 2013 Tuesday, the City of Toronto. This week: Hillcrest Village +3.5% -36.0% Between 2001 and 2011, the number After more than doubling between of people in Hillcrest Village who listed 2001 and Hillcrest Village: Population (2011): 17,650 English as their Home Language has 2006, the increased by 3.5 per cent, though total number NORTH YORK MIRROR | NORTH that number has decreased by 6.3 per of people LANGUAGES cent since 2006. listing Persian (Farsi) as their Home Language Russian Chinese, Mandarin and Cantonese are dropped significantly between 2006 Korean common non-official languages in Hill- and 2011: by 36 per cent. RomanianSpanish Persian crest Village. In the 2011 census, 42.2 +23.3% Arabic per cent of residents listed one of The number of people in the 65+ age CITY MOTHER TONGUE the three as their Mother Tongue, and group (Seniors) has grown 23.3 per Chinese “Mother Tongue” refers to the first Cantonese 34 per cent listed one of the three as CONTEXT cent between 2001 and 2011. This is -14.1% language learned at home in childhood and their Home Language. the only age group to have grown in The number of people in Hillcrest Mandarin still understood at the time of the census. -

Hillcrest Village

2016 NEIGHBOURHOOD PROFILE NEIGHBOURHOOD # 48. Hillcrest Village STEELES AVE E V I C D T O O N R M I D A U I L P N L A C S A R N R K C D R A E V E E K 4 0 4 Y A T W S H G E I I L H S E L E LL AVE V MCNICO A S M H A R B FINCH AVE E Neighbourhood Snapshot Population 16,934 Population Change 2011-2016 -4.1% Population Density 3,148 people per square km Population 800 Female 600 Female 400 200 53.2% 0 200 Male Male 400 600 800 46.8% 0-4 5-9 100+ 10-14 15-19 20-24 25-29 30-34 35-39 40-44 45-49 50-54 55-59 60-64 65-69 70-74 75-79 80-84 85-89 90-94 95-99 Children Youth Working Age Pre-Retirement Seniors 0-14 years 15-24 years 25-54 years 55-64 years 65+ years 2,110 (12%) 2,155 (13%) 6,055 (36%) 2,270 (13%) 4,300 (25%) City Rate: 15% City Rate: 12% City Rate: 45% City Rate: 12% City Rate: 16% Prepared by Social Policy, Analysis & Research Source: Statistics Canada, 2016 Census of Population Neighbourhoods data set at: www.toronto.ca/open Copyright 2018 City of Toronto. All rights reserved. Visit Wellbeing Toronto: www.toronto.ca/wellbeing Published: Februrary 2018 Contact: [email protected] 1 2016 NEIGHBOURHOOD PROFILE Notes This profile has been automatically generated from the Social Data Warehouse maintained by the Social Policy, Analysis and Research (SPAR) Unit of the Social Development, Finance & Administration Division. -

Child & Family Inequities Score

CHILD & FAMILY INEQUITIES SCORE Technical Report The Child & Family Inequities Score provides a neighbourhood-level measure of the socio-economic challenges that children and families experience. The Child & Family Inequities Score is a tool to help explain the variation in socio-economic status across the City of Toronto neighbourhoods. It will help service providers to understand the context of the neighbourhoods and communities that they serve. It will also help policy makers and researchers understand spatial inequities in child and family outcomes. While other composite measures of socio-economic status in the City exist, the Child & Family Inequities Score is unique because it uses indicators that are specific to families with children under the age of 12. The Child & Family Inequities Score is a summary measure derived from indicators which describe inequities experienced by the child and family population in each of Toronto’s 140 neighbourhoods. The Child & Family Inequities Score is comprised of 5 indicators: • Low Income Measure: Percent of families with an after-tax family income that falls below the Low Income Measure. • Parental Unemployment: Percent of families with at least one unemployed parent / caregiver. • Low Parental Education: Percent of families with at least one parent / caregiver that does not have a high school diploma. • No Knowledge of Official Language: Percent of families with no parents who have knowledge of either official language (English or French). 1 • Core Housing Need: Percent of families in core housing need . This report provides technical details on how the Child & Family Inequities Score was created and describes how the resulting score should be interpreted. -

City of Toronto Map with 73 Bias

73 BUSINESS IMPROVEMENT AREAS STEELES AVE E LESLIE ST LESLIE ALBION RD TAPSCOTT RD 24 DREWRY AVE CUMMER AVE 39 MCNICOLL AVE 08 BRIMLEY RD 01 FINCH AVE W WILLOWDALEAVE 26 404 HIGHWAY FINCH AVE E WESTON RD WESTON 42 JANE ST JANE 41 HIGHWAY 400 HIGHWAY 23 WILLIAM R ALLEN RD ALLEN R WILLIAM MARTINGROVE RD HUNTINGWOOD DR 01 10 MIDLAND AVE 33 MCCOWANRD REXDALE BLVD WILSONHEIGHTS BLVD SHEPPARD AVE W HIGHWAY 427 07 ST BATHURST 59 SHEPPARD AVE E KEELE ST KEELE BAYVIEW AVE BAYVIEW 40 09 HIGHWAY27 HIGHWAY 401 02 HIGHWAY 401 PROGRESS AVE YORK MILLS RD WILSON AVE 36 HIGHWAY 409 HIGHWAY 401 ELLESMERE RD MILITARY TRL BRIDGELAND AVE PORTUNION RD CALEDONIA RD CALEDONIA 25 MARKHAMRD ORTONPARK RD AVENUE RD SCARBOROUGHGOLF CLUBRD WILLIAMR ALLEN RD 44 DIXON RD 72 34 LAWRENCE AVE W 37 38 69 ST KEELE MOUNTPLEASANT RD LAWRENCE AVE E SCARLETT RD 151515 43 DON MILLS RD MILLS DON 12 ST DUFFERIN 70 BIRCHMOUNTRD BLACK CREEKDR MORNINGSIDEAVE THE WESTWAY BELLAMYRD N 65 KINGSTON RD EGLINTON AVE W 11 EGLINTON AVE E ISLINGTONAVE 48 24 27 73 64 25 HIGHWAY427 GUILDWOOD PKWY ORIOLE PKWYORIOLE DANFORTH RD KIPLINGAVE LAIRDDR RENFORTHDR 04 ROYALYORK RD SPADINA RD 49 VICTORIAPARK AVE KENNEDYRD DAVISVILLE AVE WARDEN AVE 50 ST YONGE OVERLEA BLVD 03 29 MOORE AVE ST CLAIR AVE W RATHBURN RD ST CLAIR AVE E 60 15 55 33 71 DON VALLEY PARKWAY DUNDAS ST W SYMINGTONAVE GREENWOODAVE O CONNOR DR DAVENPORT RD DONLANDSAVE WOODBINEAVE PHARMACY AVE BURNHAMTHORPE RD COXWELL AVE Lake Ontario 35 58 36 ANNETTE ST DUPONT ST PAPEAVE DAWES RD KEELE KEELE ST 51 02 23 58 66 BLOOR ST W LANSDOWNE AVE 20 -

The Office of Last Resort

T O R O N T O O M B U D S M A N A N N U A L R E P O R T 2 0 1 0 AGINCOURT NORTH · AGINCOURT SOUTH-MALVERN WEST · ALDERWOOD · ANNEX · BANBURY-DON MILLS · BATHURST MANOR · BAY STREET CORRIDOR · BAYVIEW VILLAGE · BAYVIEW WOODS-STEELES · BEDFORD PARF-NORTOWN · BEECHBOROUGH-GREENBROOF · BENDALE · BIRCH- CLIFFE-CLIFFSIDE · BLACF CREEF · BLAFE-JONES · BRIAR HILL-BELGRAVIA · BRIDLE PATH-SUNNYBROOF-YORF MILLS · BROADVIEW NORTH · BROOFHAVEN-AMESBURY · CABBAGETOWN-SOUTH ST. JAMES TOWN · CALEDONIA-FAIRBANF · CASA LOMA · CENTENNIAL SCARBOROUGH · CHURCH-YONGE CORRIDOR · CLAIRLEA-BIRCHMOUNT · CLANTON PARF · CLIFFCREST · CORSO ITALIA-DAVENPORT · CRESCENT TOWN · DAN- FORTH VILLAGE – EAST YORF · DANFORTH VILLAGE – TORONTO · DON VALLEY VILLAGE · DORSET PARF · DOVERCOURT-WALLACE EMERSON- JUNCTION · DOWNSVIEW-RODING-CFB · DUFFERIN GROVE · EAST END-DANFORTH · EDENBRIDGE-HUMBER VALLEY · EGLINTON EAST · ELMS- OLD REXDALE · ENGLEMOUNT-LAWRENCEThis page has been · ERINGATE-CENTENNIAL-WEST intentionally left blank. DEANE · ETOBICOFE WEST MALL · FLEMINGDON PARF · FOREST HILL NORTH · FOREST HILL SOUTH · GLENFIELD-JANE HEIGHTS · GREENWOOD-COXWELL · GUILDWOOD · HENRY FARM · HIGH PARF NORTH · HIGH PARF-SWANSEA · HIGHLAND CREEF · HILLCREST VILLAGE · HUMBER HEIGHTS-WESTMOUNT · HUMBER SUMMIT · HUMBERMEDE · HUMEWOOD- CEDARVALE · IONVIEW · ISLINGTON-CITY CENTRE WEST · JUNCTION AREA · FEELESDALE-EGLINTON WEST · FENNEDY PARF · FENSINGTON-CHI- NATOWN · FINGSVIEW VILLAGE-THE WESTWAY · FINGSWAY SOUTH · L’AMOREAUX · LAMBTON BABY POINT · LANSING-WESTGATE · LAWRENCE PARF NORTH · -

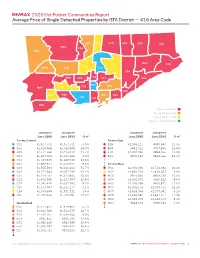

2020 Hot Pocket Communities Report Average Price of Single-Detached Properties by GTA District — 416 Area Code

2020 Hot Pocket Communities Report Average Price of Single-Detached Properties by GTA District — 416 Area Code C07 C14 C15 E05 E07 E11 W05 C06 W10 E09 E10 C04 C13 W09 W04 C12 E04 C10 W03 C03 C11 E08 C09 C02 E03 W08 W02 E06 W07 W01 E01 E02 C01 C08 W06 10 per cent plus 5 to 9.99 per cent 0 to 4.99 per cent -0.1 per cent and under January to January to January to January to June, 2020 June, 2019 % +/- June, 2020 June, 2019 % +/- Toronto Central Toronto East C01 $1,877,541 $1,953,511 -3.9% E08 $1,068,117 $940,684 13.5% C02 $2,918,968 $2,322,849 25.7% E09 $851,321 $767,846 10.9% C03 $2,371,546 $2,014,072 17.7% E10 $1,002,285 $884,955 13.3% C04 $2,217,913 $2,199,122 0.9% E11 $900,195 $801,262 12.3% C06 $1,397,835 $1,228,539 13.8% C07 $1,822,344 $1,662,244 9.6% Toronto West C08 $2,555,500 $1,641,813 55.7% W01 $2,050,596 $1,731,382 18.4% C09 $3,127,643 $3,687,292 -15.2% W02 $1,465,726 $1,410,057 3.9% C10 $2,109,727 $1,873,935 12.6% W03 $911,833 $824,133 10.6% C11 $2,430,505 $2,193,747 10.8% W04 $1,005,070 $926,819 8.4% C12 $3,346,422 $3,697,343 -9.5% W05 $1,018,398 $900,831 13.1% C13 $1,673,994 $1,624,177 3.1% W06 $1,202,176 $1,034,415 16.2% C14 $2,039,649 $1,971,731 3.4% W07 $1,435,099 $1,377,081 4.2% C15 $1,702,456 $1,533,291 11.0% W08 $1,693,382 $1,447,217 17.0% W09 $1,094,075 $1,039,140 5.3% Toronto East W10 $814,105 $758,751 7.3% E01 $1,471,647 $1,378,987 6.7% E02 $1,691,725 $1,514,577 11.7% E03 $1,197,161 $1,099,204 8.9% E04 $935,655 $836,585 11.8% E05 $1,086,239 $983,589 10.4% E06 $1,095,287 $924,872 18.4% E07 $1,002,731 $892,010 12.4%