The Interpretation of Psalm 11 by W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Asterius on Psalm 11 Homily 2 As Is Well Known, the Tenth Century Hebrew Masoretic Text (MT) Used for Modern Bible Translations

Asterius On Psalm 11 Homily 2 As is well known, the tenth century Hebrew Masoretic Text (MT) used for modern Bible translations has 150 psalms whereas the Psalter in the Septuagint (LXX) has 151 psalms. This homily is based on Psalm 11 LXX which is Psalm 12 MT. Most psalms have a title or superscription which may include names of composers or people to whom a psalm is committed, situational details, genre, and liturgical directions.1 Whether these superscriptions were part of the original composition is unknown. In any case, the superscriptions are incorporated into the psalm text in the Hebrew MT, such that when the text was versified in the sixteenth century, they were counted as the first verse. This incorporaton is already evident in some of the psalm fragments found among the Dead Sea Scrolls. For example, the oldest fragment 4QPsa (= 4Q83, mid second century BCE) shows ‘no special separation between title and text’.2 More tellingly, 4QpPsa (= 4Q171 Pesher Psalms) which contains commentary on Psalm 45, includes commentary on its superscription, as if it were part of the psalm proper.3 Early Christians who used the LXX also considered the psalm title or superscription to be part of scripture and would exegete it as such. The superscription for Psalm 11 LXX in the Hebrew MT reads: ‘To the leader: according to The Sheminith. A Psalm of David.’ In the Greek LXX it reads: ‘To the end, upon the eighth. A Psalm of David’.4 Asterius spends considerable time in the first part of the homily expounding this title, and in particular the significance of the eighth day in redemption history. -

Psalms Psalm

Cultivate - PSALMS PSALM 126: We now come to the seventh of the "Songs of Ascent," a lovely group of Psalms that God's people would sing and pray together as they journeyed up to Jerusalem. Here in this Psalm they are praying for the day when the Lord would "restore the fortunes" of God's people (vs.1,4). 126 is a prayer for spiritual revival and reawakening. The first half is all happiness and joy, remembering how God answered this prayer once. But now that's just a memory... like a dream. They need to be renewed again. So they call out to God once more: transform, restore, deliver us again. Don't you think this is a prayer that God's people could stand to sing and pray today? Pray it this week. We'll pray it together on Sunday. God is here inviting such prayer; he's even putting the very words in our mouths. PSALM 127: This is now the eighth of the "Songs of Ascent," which God's people would sing on their procession up to the temple. We've seen that Zion / Jerusalem / The House of the Lord are all common themes in these Psalms. But the "house" that Psalm 127 refers to (in v.1) is that of a dwelling for a family. 127 speaks plainly and clearly to our anxiety-ridden thirst for success. How can anything be strong or successful or sufficient or secure... if it does not come from the Lord? Without the blessing of the Lord, our lives will come to nothing. -

At Home Study Guide Praying the Psalms for the Week of May 15, 2016 Psalms 1-2 BETHELCHURCH Pastor Steven Dunkel

At Home Study Guide Praying the Psalms For the Week of May 15, 2016 Psalms 1-2 BETHELCHURCH Pastor Steven Dunkel Today we start a new series in the Psalms. The Psalms provide a wonderful resource of Praying the Psalms inspiration and instruction for prayer and worship of God. Ezra collected the Psalms which were written over a millennium by a number of authors including David, Asaph, Korah, Solomon, Heman, Ethan and Moses. The Psalms are organized into 5 collections (1-41, 42-72, 73-89, 90-106, and 107-150). As we read the book of Psalms we see a variety of psalms including praise, lament, messianic, pilgrim, alphabetical, wisdom, and imprecatory prayers. The Psalms help us see the importance of God’s Word (Torah) and the hopeful expectation of God’s people for Messiah (Jesus). • Why is the “law of the Lord” such an important concept in Psalm 1 for bearing fruit as a follower of Jesus? • In John 15, Jesus says that apart from Him you can do nothing. Compare the message of Psalm 1 to Jesus’ words in John 15. Where are they similar? • Psalm 2 tells of kings who think they have influence and yet God laughs at them (v. 3). Why is it important that we seek our refuge in Jesus (2:12)? • Our heart for Bethel Church in this season is that we would saturate ourselves with God’s Word, specifically the book of Psalms. We’ve created a reading plan that allows you to read a Psalm a day or several Psalms per day as well as a Proverb. -

Predator, Prey and Protector

Predator, Prey, and Protector: Helping Victims Think and Act from Psalm 10 by David Powlison elen had been betrayed by her hus- insubstantial and insecure. All along, gen- band. He had played the part of the uine faith in God as refuge had intertwined Hdutiful, churchgoing husband, with Helen’s tendencies towards keeping father, and provider for many years. Their up appearances: “Put up with it, keep quiet, two children were in college. But unbe- pretend it’s not really happening, and every- knownst to Helen, he had maintained mis- thing’s OK.” Now she couldn’t keep silent. tresses in three cities. Helen had trusted him Now she couldn’t stand it any longer. Now with all the family finances, including a half- she couldn’t pretend. She was in trouble. million dollars she had inherited. He What should she say? How should she siphoned off all her money into his name. think? What should she do? Where does He spent much of it and ran up debts God fit amidst such devastation? Psalm 10 besides, financing a lifestyle of gambling, was uttered and written for those who have immorality, and partying. She’d been igno- rant of the adulteries and fraud, but she was not unaware of other evils. For many years their sexual relationship had been a private Psalm 10 is a message of honest agony to Helen. He routinely forced her to anguish and genuine refuge. commit acts she found repellent. In public his demeanor was usually pleasant; he was seemingly good-natured, quick-witted, worldly-wise, successful, confident, respon- been victimized by others. -

Observations and Reflections on the Giant Psalm

CONCORDIA THEOLOGICAL QUARTERLY Volume 42 Number 1 JANUARY 1978 An Evaluation of the Australian Lutheran "Statement on Homosexuality" ....Robert W. Schaibley 1 Observations and Reflections on the Giant Psalm .................... Raymond F. Surburg 8 flighlights of the Lutheran Reformation in Slovakia .......................... David P. Daniel 21 Theological Observer .................................. 35 Homiletical Studies ................................... 39 Book Reviews ........................................ 80 Books Received ....................................... 99 Observations and Reflections on the Giant Psalm Raymond F. Surburg Psalm 119 is outstanding in a number of ways. It is the longest of the 150 poems comprising the Book of Psalms. Its 176 verses make it the longest chapter in the Bible. Psalm 119 is two chapters removed from the middle chapter of the English Bible (which is also the shortest chapter of the Bible). It is one of thirty-four psalms which in the Hebrew have no super- scription (and is therefore called an orphan psalm). One of the Dead Sea manuscripts from Cave 11 has 114 of the original 176 verses.' This unique poem has been called the "alphabet of Divine Love," "the school of truth," "the storehouse of the Holy Spirit, " "the paradise of all Doctrines as well as the deep mystery of the Scriptures, where the whole moral discipline of all virtues shines brightly. "* The author of this giant among the psalms is not known. Luther and Spurgeon believed David to be its a~thor.~Others favor Ezra4 or some individual living in the time of Ezra and Nehemiah.5 Pieters does not believe that the author lived during the postexilic period but at a time when the author is being persecuted by "princes" (v. -

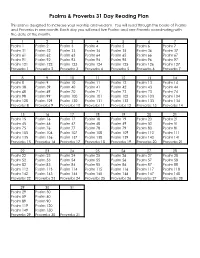

Psalms & Proverbs 31 Day Reading Plan

Psalms & Proverbs 31 Day Reading Plan This plan is designed to increase your worship and wisdom. You will read through the books of Psalms and Proverbs in one month. Each day you will read five Psalms and one Proverb coordinating with the date of the month. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Psalm 1 Psalm 2 Psalm 3 Psalm 4 Psalm 5 Psalm 6 Psalm 7 Psalm 31 Psalm 32 Psalm 33 Psalm 34 Psalm 35 Psalm 36 Psalm 37 Psalm 61 Psalm 62 Psalm 63 Psalm 64 Psalm 65 Psalm 66 Psalm 67 Psalm 91 Psalm 92 Psalm 93 Psalm 94 Psalm 95 Psalm 96 Psalm 97 Psalm 121 Psalm 122 Psalm 123 Psalm 124 Psalm 125 Psalm 126 Psalm 127 Proverbs 1 Proverbs 2 Proverbs 3 Proverbs 4 Proverbs 5 Proverbs 6 Proverbs 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Psalm 8 Psalm 9 Psalm 10 Psalm 11 Psalm 12 Psalm 13 Psalm 14 Psalm 38 Psalm 39 Psalm 40 Psalm 41 Psalm 42 Psalm 43 Psalm 44 Psalm 68 Psalm 69 Psalm 70 Psalm 71 Psalm 72 Psalm 73 Psalm 74 Psalm 98 Psalm 99 Psalm 100 Psalm 101 Psalm 102 Psalm 103 Psalm 104 Psalm 128 Psalm 129 Psalm 130 Psalm 131 Psalm 132 Psalm 133 Psalm 134 Proverbs 8 Proverbs 9 Proverbs 10 Proverbs 11 Proverbs 12 Proverbs 13 Proverbs 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Psalm 15 Psalm 16 Psalm 17 Psalm 18 Psalm 19 Psalm 20 Psalm 21 Psalm 45 Psalm 46 Psalm 47 Psalm 48 Psalm 49 Psalm 50 Psalm 51 Psalm 75 Psalm 76 Psalm 77 Psalm 78 Psalm 79 Psalm 80 Psalm 81 Psalm 105 Psalm 106 Psalm 107 Psalm 108 Psalm 109 Psalm 110 Psalm 111 Psalm 135 Psalm 136 Psalm 137 Psalm 138 Psalm 139 Psalm 140 Psalm 141 Proverbs 15 Proverbs 16 Proverbs 17 Proverbs 18 Proverbs 19 Proverbs 20 Proverbs 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 Psalm 22 Psalm 23 Psalm 24 Psalm 25 Psalm 26 Psalm 27 Psalm 28 Psalm 52 Psalm 53 Psalm 54 Psalm 55 Psalm 56 Psalm 57 Psalm 58 Psalm 82 Psalm 83 Psalm 84 Psalm 85 Psalm 86 Psalm 87 Psalm 88 Psalm 112 Psalm 113 Psalm 114 Psalm 115 Psalm 116 Psalm 117 Psalm 118 Psalm 142 Psalm 143 Psalm 144 Psalm 145 Psalm 146 Psalm 147 Psalm 148 Proverbs 22 Proverbs 23 Proverbs 24 Proverbs 25 Proverbs 26 Proverbs 27 Proverbs 28 29 30 31 Psalm 29 Psalm 30 Psalm 59 Psalm 60 Psalm 89 Psalm 90 Psalm 119 Psalm 120 Psalm 149 Psalm 150 Proverbs 29 Proverbs 30 Proverbs 31. -

Metrical Psalter Book 1 V 1-0-3

The Psalms in metre Book 1 Psalms 1-41 Book 1 ; Page 1 © Dru Brooke-Taylor 2015, the author’s moral rights have been asserted. For further information both on copyright and how to use this material see https://psalmsandpsimilar.wordpress.com v 1.0.3 : 15 vi 2015 Book 1 ; Page 2 Table of Contents Psalm 1 (SHa) CM 5 Psalm 2 (SHa)CM 6 Psalm 3 (SHa) CM 8 Psalm 4 (SHa)CM 10 Psalm 5 (TBa) CM 11 Psalm 6 (TBa) CM 13 Psalm 7 (SHa) CM 14 Psalm 8 (SHa) CM 16 Psalm 8-B (DBT) 13,13,13,13,13,13 18 Psalm 9 (SHa) CM 20 Psalm 10 (SHa) CM 22 Psalm 11 (DBT) CM 24 Psalm 12 - (SHa) CM 25 Psalm 13 (SHa) CM 26 Psalm 14 - (SHa) CM 27 Psalm 14-B - Another version (TB unaltered) LM 28 Psalm 15 - (SHa) CM 30 Psalm 16 - (SHa) CM 31 Psalm 17 - (SHa) CM 33 Part 2 34 Psalm 18 - (SHa) CM 35 Psalm 19 (SHa) CM 40 Psalm 20 (SHa) CM 42 Psalm 21 (SHa) DCM 43 Psalm 22 (SHa) CM 45 Part 2 46 Part 3 46 Psalm 23 (R) CM 48 Psalm 23 - B (SHa) CM 48 Psalm 23 - C A version by Sir H. W. Baker 8787 49 Psalm 23 - D - a version by Addison 88 88 88 50 Psalm 24 (TBa) DCM 52 Psalm 24 - B Dr Watts version to Kingsbridge in LM 54 Part 2 55 Psalm 25 (SHa) DSM 56 Part 2 57 Psalm 26 (SHa) CM 59 Psalm 27 (SHa) CM 60 Psalm 28 (SHa) CM 62 Psalm 29 (SHa) CM 63 Psalm 30 (DBT) DCM 65 Psalm 31 (SHa) CM 67 Psalm 32 (SHa) CM 70 Psalm 33 (TB) CM 72 Part 2 73 Psalm 34 (TB) CM 74 Part 2 75 Psalm 35 (TBa) CM 76 Book 1 ; Page 3 Part 2 77 Part 3 77 Psalm 36 (SHa) CM 79 Psalm 37 (TBa) 888 888 81 Part 2 82 Part 3 83 Part 3 84 Psalm 38 (SHa) CM 86 Part 2 87 Psalm 39 (SHa) CM 88 Psalm 40 (SHa) CM 90 Psalm 40 - B (TBa) LM 92 Psalm 41 (SHa) DCM 94 Book 1 ; Page 4 Psalm 1 (SHa) CM Playford has a good tune in three line harmony, which floats between Emi and G Maj, which is below as ‘Old First’ with the addition of an alto line and some ornamentation. -

Psalm 12.Pdf

1 | P a g e PSALM 12 - The Lord responds to the cry of those oppressed by the deceptive talk of the wicked - Author: Eugene Viljoen © 2015 www.christianstudylibrary.org For any questions about this Scripture passage or the notes, please contact us through the Contact Us tab on the website. Introduction and setting It is not possible to determine a precise context for this psalm. What is clear is that it is about the power of words/speech. There is a strong contrast in this psalm; it concerns the destructive use of the tongue/speech by the wicked versus the life-giving words of the Lord. Evil speech is revealed in its gross godlessness and contrasted with the trustworthy speech of God. Nothing less than salvation from the Lord is the only hope against the destruction of deceptive and lying speech. Again, the shocking reality is that this evil and destructive use of the tongue is by the “neighbour” (vs. 2); in Israel that means those that form part of the Lord’s covenant people! Psalm 12 is a prayer or part of a worship service performed in a time of crisis comparable to the crisis depicted in Psalm 11, where the foundations of life together as people of God are overthrown. The society of the people of the Lord disintegrates where the use of the tongue is not curbed and disciplined to speak that which is truthful. The part of the foundation that is overthrown and destroyed is just/truthful speech. Form and structure In Psalm 12 a speaker pleads with the Lord on behalf of the innocent in verses 1-4. -

1 Samuel W/Associated Psalms

1 Samuel w/Associated Psalms Purpose : Israel should hope in the Davidic line, despite the trouble caused by David’s shortcomings. Outline : 1.1:1-1.7:17 – Foundation of the Kingdom (Birth of Samuel, Capture and return of the Ark) 1.8:1-1.15:35 – Saul’s Kingdom (Israel asks for a king, Saul anointed as king, Samuel rebukes/Lord rejects Saul) 1.16:1-2:20:26 – David’s Kingdom (David and Goliath, Saul’s jealousy of David, Covenant with David, Bathsheba) 2.21:1-2.24:25 – Future of the Kingdom (David’s Census) Author : Samuel & later authors/editors (perhaps prophets) Date : Reign of Saul – 1050-1010 --- Reign of David – 1010-970 Reading 1 Samuel with Associated Psalms (April 8-20): -1&2 Samuel were originally one book, and later divided by the Septuagint (Greek translation of the Old Testament).There is a changing Political landscape – Moabites, Midianites, Ammonites, and Philistines during the period of the Judges. During Saul and David the Philistines are the major enemy.Literary device for the United monarchy (Saul, David, Solomon): 1) Appointment 2) Successes and Potential 3) Failures and Results of Failures. Chapters1-7– Foundation of the Kingdom -Chapter 1: The Birth of Samuel Birth and dedication of Samuel. Father is Elkanah, Mother is Hannah! Hannah makes a vow in 1.1:10-11. She gives birth to Samuel and he is dedicated and raised under Eli the Priest. -Chapter 2: Hannah’s Prayer Compare Sons of Eli and Samuel (1.2:12-17 vs. 1.2:18). Compare Samuel and Jesus (1.2:26 and Luke 2:52). -

Fr. Lazarus Moore the Septuagint Psalms in English

THE PSALTER Second printing Revised PRINTED IN INDIA AT THE DIOCESAN PRESS, MADRAS — 1971. (First edition, 1966) (Translated by Archimandrite Lazarus Moore) INDEX OF TITLES Psalm The Two Ways: Tree or Dust .......................................................................................... 1 The Messianic Drama: Warnings to Rulers and Nations ........................................... 2 A Psalm of David; when he fled from His Son Absalom ........................................... 3 An Evening Prayer of Trust in God............................................................................... 4 A Morning Prayer for Guidance .................................................................................... 5 A Cry in Anguish of Body and Soul.............................................................................. 6 God the Just Judge Strong and Patient.......................................................................... 7 The Greatness of God and His Love for Men............................................................... 8 Call to Make God Known to the Nations ..................................................................... 9 An Act of Trust ............................................................................................................... 10 The Safety of the Poor and Needy ............................................................................... 11 My Heart Rejoices in Thy Salvation ............................................................................ 12 Unbelief Leads to Universal -

A Note on Psalm 11

Vetus Testamentum 67 (2017) 470-479 Vetus Testamentum brill.com/vt The Bird and the Mountains: A Note on Psalm 11 Cat Quine Department of Theology & Religious Studies University of Nottingham [email protected] Abstract This paper demonstrates that the bird and the mountains phrase in Ps 11:1 compares well with a common metaphor relating to siege warfare and military conquest found in Neo-Assyrian royal inscriptions and considers the resulting implications. Keywords Psalms – Neo-Assyrian royal inscriptions – Siege warfare Psalm 11 is often regarded as unremarkable albeit at points textually and form- critically awkward.1 However, in what follows we will demonstrate that the image of a bird fleeing to the mountains in 11:1 is very similar to a similar phrase commonly found in Neo-Assyrian royal inscriptions. * This research was undertaken with funding from a HEFCE Oxford Graduate Scholarship and subsequent support from Midlands3Cities AHRC Doctoral Training Partnership. Thanks are due to my supervisor Dr. C. L. Crouch for her assistance with earlier drafts of this paper and also to the reviewers for their insightful comments. 1 Cf. comments in Erhard S. Gerstenberger, Psalms Part 1 with an Introduction to Cultic Poetry (FOTL XIV; Grand Rapids, 1988), pp. 76-78; F.-L. Hossfeld and Erich Zenger, Die Psalmen I: Psalm 1-50 (Würzburg, 1993), p. 88. Gerstenberger argues it is a psalm of contest but most others view it as a psalm of trust, or confidence, e.g. Richard J. Clifford, Psalms 1-72 (AOTC; Nashville, 2002), p. 76; Peter C. Craigie, Psalms 1-50 (WBC 19; Waco, 1983), p. -

Banquet Without Walls Richard Leach

Banquet without Walls Hymns on the Psalms Richard Leach Printed on recycled and acid-free paper Banquet without Walls: Hymns on the Psalms by Richard Leach Copyright © 2009 Selah Publishing Co., Inc., Pittsburgh, Pa. 15227 www.selahpub.com All rights reserved. All pieces in this collection are under copyright protection of the copyright holder listed with each hymn. Permission must be obtained from the copyright holder to reproduce—in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise—what is included in this book. All of the hymn texts and copyrights held by Selah Publishing Co. may be used by congregations enrolled in the C.C.L.I., LicenSing, or OneLicense.net programs. Typeset and printed in the United States of America. Back cover photo by Alexander Leach, 2005. First edition 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 13 12 11 10 09 Catalog no. 125-429 Contents Note…4 Introduction …5 Psalms…7 Indexes…156 Note To indicate on a text’s page whether it has ever been set to music, the page notes may include a choral setting or an unpublished tune. See the Publications index for information on books cited in the footnotes. 4 Introduction “Banquet without walls” is a phrase I wrote for the table set before us in the presence of our enemies in Psalm 23, and for the dinner tables at which Jesus welcomes outcasts. It also describes the Psalter itself, which has hosted so many singers and interpreters, in very many languages and musical styles, in countless synagogues, churches and other gatherings of God’s people, through the thousands of years since the psalms were writ- ten and collected.