Engaging Faith Communities in Urban Regeneration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PDF995, Job 6

The Wildlife Trust for Birmingham and the Black Country _____________________________________________________________ The Endless Village Revisited Technical Background December 2005 Protecting Wildlife for the Future The Endless Village Revisited Technical Background 2005 The Wildlife Trust for Birmingham and the Black Country gratefully acknowledges support from English Nature, Dudley MBC, Sandwell MBC, Walsall MBC and Wolverhampton City Council. This Report was compiled by: Dr Ellen Pisolkar MSc IEEM The Endless Village Revisited Technical Background 2005 The Endless Village Revisited Technical Background 2005 Contents Page 1. INTRODUCTION 1 2. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 2 3. SITES 4 3.1 Introduction 4 3.2 Birmingham 3.2.1 Edgbaston Reservoir 5 3.2.2 Moseley Bog 11 3.2.3 Queslett Quarry 17 3.2.4 Spaghetti Junction 22 3.2.5 Swanshurst Park 26 3.3 Dudley 3.3.1 Castle Hill 30 3.3.2 Doulton’s Claypit/Saltwells Wood 34 3.3.3 Fens Pools 44 3.4 Sandwell 3.4.1 Darby’s Hill Rd and Darby’s Hill Quarry 50 3.4.2 Sandwell Valley 54 3.4.3 Sheepwash Urban Park 63 3.5 Walsall 3.5.1 Moorcroft Wood 71 3.5.2 Reedswood Park 76 3.5 3 Rough Wood 81 3.6 Wolverhampton 3.6.1 Northycote Farm 85 3.6.2 Smestow Valley LNR (Valley Park) 90 3.6.3 West Park 97 4. HABITATS 101 The Endless Village Revisited Technical Background 2005 4.1 Introduction 101 4.2 Heathland 103 4.3 Canals 105 4.4 Rivers and Streams 110 4.5 Waterbodies 115 4.6 Grassland 119 4.7 Woodland 123 5. -

Wolverhampton “Listed” Trader Scheme April 2020 to March 2021 Issue 8

Wolverhampton CITY OF WOLVERHAMPTON C O U N C I L Word of Mouth Wolverhampton “Listed” Trader Scheme April 2020 to March 2021 Issue 8 Building and Carpentry * Cleaning Services Conservatories & Orangeries * Damp Proofing Domestic Appliance Installation & Repairs * Electrical Garage Doors * Gardening & Tree Services General Household Jobs * Home Security & Locksmiths Mobility Aids & Services * Painting & Decorating Plastering & Tiling * Plumbing, Heating & Drainage Roofing* TV Services & Aerials Window Fitting & Repair This list of contractors and service providers is compiled by Age UK Wolverhampton and Wolverhampton Trading Standards from unsolicited recommendations provided by previously satisfied customers. We have endeavoured to include only reliable trades people who will do a professional job at a fair price. The price charged is in no way subsidised or discounted to users of this list. IMPORTANT DISCLAIMER: Neither Wolverhampton Trading Standards nor Age UK Wolverhampton can be held accountable for any dispute resulting from the use of a listed trader. The partnership CANNOT accept any liability for, or underwrite the quality of any work done by listed traders. The provision of this list to you does not imply recommendation or approval from Age UK Wolverhampton or Wolverhampton Trading Standards. We trust you will receive a good service from the traders listed and we welcome and actively encourage your comments as these are very important, not only to us but also to all future users of the Word of Mouth booklet. When using traders from this list it is therefore MOST IMPORTANT that you complete the enclosed SATISFACTION SURVEY*, with your comments - GOOD or BAD. Two copies are included in this brochure and additional copies can be obtained from Age UK Wolverhampton. -

Directory of Mental Health Services in Wolverhampton

Directory of Mental Health Services In Wolverhampton 2019 - 2024 Contents Title Page Introduction 1 Emergency Contacts 2 Services for 18 years and over Section 1: Self-referral, referral, and support groups 4 Section 2: Community support services, self-referral and professional 14 referrals Section 3: Services that can be accessed through the Referral and 22 Assessment Service (RAS) Section 4: Services for carers 27 Section 5: Specialist housing services 29 Section 6: Contacts and useful websites 33 Services for 65 years and over Section 1: Community support services – self-referral and 37 professional referrals Section 2: Referral from a General Practitioner (GP) and other 40 agencies Section 3: Contact and useful websites 44 Services for Children and Young People Emergency Contacts 45 Section 1: Referral, self-referral / support groups 47 Section 2: Community support services, self - referral referrals and 50 professional referrals Section 3: Social Care /Local Authority Services 52 Section 4: Services that need a referral from a General Practitioner 54 (GP) and Professional Section 5: Useful websites and contacts 58 0 Introduction Good mental health plays a vital impact upon our quality of life and has an effect upon our ability to attain and maintain good physical health and develop positive relationships with family and friends. Positive mental health also plays a part in our ability to achieve success educationally and achieve other life goals and ambitions including those related to work, hobbies, our home life and sporting and leisure activities. As many as 1 in 4 adults and 1 in 10 children experience mental ill health during their life time. -

Murrle Bennett: the Anglo-German Style

To print, your print settings should be ‘fit to page size’ or ‘fit to printable area’ or similar. Problems? See our guide: https://atg.news/2zaGmwp 7 1 -2 0 2 1 9 1 ISSUE 2488 | antiquestradegazette.com | 17 April 2021 | UK £4.99 | USA $7.95 | Europe €5.50 S E E R 50years D koopman rare art V A I R N T antiques trade G T H E KOOPMAN (see Client Templates for issue versions) THE ART M ARKET WEEKLY [email protected] +44 (0)20 7242 7624 www.koopman.art Coin auction houses end Murrle Bennett: the four-year joint venture are nine staff members (the by Laura Chesters Anglo-German style group has a total of 60 staff). It intends to hold its first auction Jewellery by the Anglo-German firm Murrle Bennett, London coin specialists back at 399 Strand in the which thrived for two decades before the First World Baldwin’s and St James’ autumn. War, appeals today for the reasons it did in the early 20th Auctions have ended their St James’ Auctions, founded tie-up after four years. by Stephen Fenton of century. The jewellery is good quality, effortlessly stylish The stopping of the joint dealership Knightsbridge and (in comparison with handmade or precious stone venture was without costs and Coins, will continue to be jewels of the period) relatively affordable. Stanley Gibbons Group based at 10 Charles II Street, St (owner of Baldwin’s) said it was James’s, in London. The Murrle Bennett output, which embraced all flavours a “major milestone” to “bring Alongside Fenton there are of European Art Nouveau, is a focus of this week’s coin auctions back in house nine full-time employees plus jewellery feature on pages 12-18. -

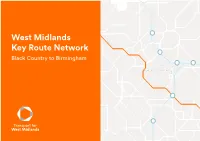

West Midlands Key Route Network

L CHF ELD STAFFORDSH RE WALSALL West MidlandsWOLVERHAMPTON Key Route Network Black Country to Birmingham WEST BROMW CH DUDLEY BRMNGHAM WARW CKSH RE WORCESTERSH RE SOL HULL COVENTRY Figure 1 12 A5 A38, A38(M), A47, A435, A441, A4400, A4540, A5127, B4138, M6 L CHF ELD Birmingham West Midlands Cross City B4144, B4145, B4148, B4154 11a Birmingham Outer Circle A4030, A4040, B4145, B4146 Key Route Network A5 11 Birmingham to Stafford A34 Black Country Route A454(W), A463, A4444 3 2 1 M6 Toll BROWNH LLS Black Country to Birmingham A41 M54 A5 10a Coventry to Birmingham A45, A4114(N), B4106 A4124 A452 East of Coventry A428, A4082, A4600, B4082 STAFFORDSH RE East of Walsall A454(E), B4151, B4152 OXLEY A449 M6 A461 Kingswinford to Halesowen A459, A4101 A38 WEDNESF ELD A34 Lichfield to Wednesbury A461, A4148 A41 A460 North and South Coventry A429, A444, A4053, A4114(S), B4098, B4110, B4113 A4124 A462 A454 Northfield to Wolverhampton A4123, B4121 10 WALSALL A454 A454 Pensnett to Oldbury A461, A4034, A4100, B4179 WOLVERHAMPTON Sedgley to Birmingham A457, A4030, A4033, A4034, A4092, A4182, A4252, B4125, B4135 SUTTON T3 Solihull to Birmingham A34(S), A41, A4167, B4145 A4038 A4148 COLDF ELD PENN B LSTON 9 A449 Stourbridge to Wednesbury A461, A4036, A4037, A4098 A4123 M6 Stourbridge to A449, A460, A491 A463 8 7 WEDNESBURY M6 Toll North of Wolverhampton A4041 A452 A5127 UK Central to Brownhills A452 WEST M42 A4031 9 A4037 BROMW CH K NGSTAND NG West Bromwich Route A4031, A4041 A34 GREAT BARR M6 SEDGLEY West of Birmingham A456, A458, B4124 A459 M5 A38 -

Agenda Item No: 91

Agenda Item No: 7 Wolverhampton City Council OPEN INFORMATION ITEM Committee / Panel PLANNING COMMITTEE Date 1st March 2011 Originating Service Group(s) REGENERATION AND ENVIRONMENT Contact Officer(s)/ STEPHEN ALEXANDER (Head of Development Control) Telephone Number(s) (01902) 555610 Title/Subject Matter APPLICATIONS DETERMINED UNDER OFFICER DELEGATION, WITHDRAWN, ETC. The attached Schedule comprises planning and other application that have been determined by authorised officers under delegated powers given by Committee, those applications that have been determined following previous resolutions of Planning Committee, or have been withdrawn by the applicant, or determined in other ways, as details. Each application is accompanied by the name of the planning officer dealing with it in case you need to contact them. The Case Officers and their telephone numbers are Wolverhampton (01902): Major applications Minor applications Other applications Ian Holiday 555630 Alan Murphy 555632 Martyn Gregory 551125 (Section Leader) (Section Leader) (Section Leader) Jenny Davies 555608 (Planning Officers) (Planning Officers) (Senior Planning Officer) Ragbir Sahota 555616 Tracey Homfray 555641 Mindy Cheema 551360 Mark Elliot 555648 Richard Pitt 551674 Marcela Quinones 555607 Ann Wheeldon 550348 (Senior Planning Officer) Colin Noakes 551132 Andrew Johnson 555604 Nussarat Malik 550141 Phillip Walker 555632 (Planning Officer) HEAD OF DEVELOPMENT CONTROL: STEPHEN ALEXANDER 555610 FAXES can be sent on 551359 or 558792 E-MAIL [email protected] Page 1 of 69 Summary of Applications Determined Under Officer Delegation Introduction 1.1 The attached schedule comprises planning and other applications that have been determined by authorised officers under delegated powers given by Committee, or those that have been withdrawn by the applicant or determined in other ways; as detailed in the schedule. -

10 Fern Leys, Finchfield, Wolverhampton, West Midlands

10 Fern Leys, Finchfield, Wolverhampton, West Midlands, WV3 9EJ 10 Fern Leys, Finchfield, Wolverhampton, West Midlands, WV3 9EJ A traditionally appointed, extended semi-detached house offering well proportioned accommodation with three / four bedrooms over two storeys standing in a sought after residential address at the heart of Finchfield (EPC: D). WOMBOURNE OFFICE. LOCATION under-unit motion sensor lights, tiled floor, double glazed window overlooking the rear Fern Leys is a small, established cul-de-sac standing at the heart of Finchfield which is a garden and double glazed external UPVC door with opaque glazed top leading to the side thriving and popular suburb to the west of Wolverhampton City Centre. There is a wide passage. A double glazed Velux window and door leads into the UTILITY ROOM with loft range of shops within easy walking distance together with a supermarket, building society, space and radiator. The garage has been converted into BEDROOM 4 with double glazed pubs and reputable schooling for all age groups. The open spaces of Bantock Park are a window to the front elevation and radiator. short distance away and there are bus routes to the further, more wide ranging amenities of the City Centre itself. The staircase with wooden balustrades rises to the first floor LANDING. The BATHROOM has been re-fitted to a very high standard with a white suite comprising walk-in shower cubicle, DESCRIPTION bath, low-level wc, vanity wash hand basin, two small chrome heated ladder towel rails, two 10 Fern Leys is a traditionally appointed, extended three/four bedroom semi-detached double glazed opaque windows to the rear elevation, tiled walls and floor. -

Uplands Avenue, Finchfield, Wolverhampton, West Midlands WV3 8AL

82, Uplands Avenue Finchfield, Wolverhampton, West Midlands WV3 8AL Offers in the region of £237,500 "AN ATTRACTIVE AND EXTENDED THREE BEDROOM TRADITIONAL SEMI-DETACHED FAMILY HOME OFFERING WELL PROPORTIONED LIVING ACCOMMODATION" This spacious family home is pleasantly situated on a popular road within walking distance of the shops and amenities offered in the sought after residential area of Finchfield. The property briefly comprises a porch, welcoming entrance hall, living room, sitting room, dining room open to the kitchen, guest w.c, family bathroom, separate w.c and three light and airy bedrooms. The property benefits from an attached single garage, a driveway providing ample off-road parking and a good size enclosed rear garden. VIEWING IS HIGHLY RECOMMENDED TO FULLY APPRECIATE THIS FAMILY HOME AND ITS CONVENIENT LOCATION 82 Uplands Avenue, Finchfield, Wolverhampton, West Midlands WV3 8AL LOCATION SITTING ROOM The property is located in an established and popular 12'4" x 11'4" (3.76 x 3.46) residential area and is within a short walking distance of the local shops and amenities in Finchfield. Further extensive facilities offered by Compton, Tettenhall Village and Wolverhampton City Centre are also within easy reach. Outdoor activities can be enjoyed all year round with the South Staffordshire Railway Walk and nature park within easy reach from this popular and established residential area. PORCH 6'6" x 2'8" (1.99 x 0.83) Having an obscure double glazed door to the front and door opening into the entrance hall. ENTRANCE HALL 12'9" x 6'4" (3.89 x 1.94) A versatile second reception room having a feature fireplace with gas fire and timber surround, picture rail, double central heating radiator, original wooden flooring and a hardwood single glazed door to the rear opening out onto the garden. -

ISSUE 2501 | Antiquestradegazette.Com | 17 July 2021 | UK £4.99 | USA $7.95 | Europe €5.50

To print, your print settings should be ‘fit to page size’ or ‘fit to printable area’ or similar. Problems? See our guide:https://atg.news/2zaGmwp 7 1 -2 0 2 1 9 1 ISSUE 2501 | antiquestradegazette.com | 17 July 2021 | UK £4.99 | USA $7.95 | Europe €5.50 S E E R 50years D V A I R N T antiques trade G T H E KOOPMAN (see Client Templates for issue versions) THE ART M ARKET WEEKLY Left: Renaissance burgonet Inkstand makes its c.1555-60 – £96,000 at Thomas Del Mar. mark among latest London auctions though the hammer price was by Alex Capon some way below the £12m-18m & Roland Arkell estimate. The price with premium added was £10.6m. The overall performance of It helped Christie’s Old the latest London sales of Master evening sale on July 8 Old Master pictures and to a £45.3m total (including ‘important’ works of art premium) with 46 of the 59 lots was fairly mixed but the selling on the night (78%), a auction houses did at least figure that surpassed the welcome the return of some £17.2m from Sotheby’s big-ticket items. equivalent sale the previous After a difficult period due evening where 28 out of 49 lots to the pandemic, last week’s sold (57.1%). series yielded a more Earlier that day, the favourable crop of Exceptional sale at Christie’s consignments. generated a premium-inclusive Pick In terms of Old Master £19.5m from 39 lots (of which pictures, Christie’s had the 30 sold) and was topped at of the pick of the works on this £7.5m by one of the last few week occasion and posted the top Leonardo drawings in private lot of the week when a view of hands (see story below). -

Response to Request for Information

[NOT PROTECTIVELY MARKED] Response to Request for Information Reference FOI 002702 Date 28 August 2018 Entertainment Licence Request: I would like to obtain or purchase a list of venues, pubs and establishments which are licenced for live entertainment which may provide entertainment by three or more musicians constituting a band. With reference to your above request, please see our response provided from page 2 onwards. Polish Catholic Club Polish Catholic Centre Stafford Road Wolverhampton West Midlands WV10 6DQ Hurst Hill Methodist Church Hall Hurst Hill Methodist Church Hall Hurst Road Lanesfield Wolverhampton West Midlands WV14 9EU Gorgeous 34-36 School Street Town Centre Wolverhampton WV1 4LF Divine Bar 77 Darlington Street City Centre Wolverhampton WV1 4LY R.A.F.A. Club Royal Air Force Association 26 Goldthorn Road Wolverhampton West Midlands WV2 4PN The Gunmakers Arms 63 Trysull Road Merry Hill / Bradmore Wolverhampton WV3 7JE Dartmouth Arms Dartmouth Arms Public House 47 Vicarage Road Parkfield Wolverhampton WV2 1DF Grand Station Grand Station Conference And Banqueting Centre Sun Street Wolverhampton West Midlands WV10 0BF The Lakshmi Restaurant 190-210 Dudley Road Blakenhall Wolverhampton WV2 3DY Wolverhampton Racecourse Dunstall Park Centre Gorsebrook Road Whitmore Reans Wolverhampton, West Midlands WV6 0PE The Robin R'n'B Club 2 26-28 Mount Pleasant Bilston Wolverhampton WV14 7LT The Cobra Lounge 30 Queen Street City Centre Wolverhampton WV1 3JW Ujamaa Limited Street Record Clifford Street Wolverhampton West Midlands Northwood -

ANNUAL REPORT 2016/2017 2 Welcome Welcome 3

ANNUAL REPORT 2016/2017 2 Welcome Welcome 3 Welcome from the Chair of Governors Work continued on our £100m Springfield security, education, brownfield research and Campus, which will provide construction community research and development, and education and training from the age of 14 a commitment to grow the number of PhDs On behalf of the Board of Governors, I commend this report to senior professional level. We secured offered and increase career opportunities to you. It highlights the many successes and achievements £8m of Higher Education Funding Council for research students. Our academic of the University of Wolverhampton’s students, staff and for England (HEFCE) Catalyst funding to community continues to undertake applied graduates during the 2016/17 academic year. regenerate the derelict brownfield site, research into a diverse range of subjects, formerly home to the Springfield Brewery. including cell peptide research which could The University’s new Strategic Plan aims to build on the Work also began on the Elite Centre for lead to a new form of male contraception, significant achievements of the institution over its 190 year Manufacturing Skills (ECMS) at the site, the use of an anti-alcoholism drug in the history. It sets out an ambitious vision for the University to which will provide world-class training treatment of pancreatic cancer and research be a progressive and influential sector leader with regional, facilities and will support the delivery of into the demise of the coal mining industry. apprenticeships through to degree level As a global University, we welcome students national and international significance. It will promote Apprenticeships. -

Wolverhampton City Council OPEN INFORMATION ITEM

Agenda Item No: 9 Wolverhampton City Council OPEN INFORMATION ITEM th Committee / Panel PLANNING COMMITTEE Date 20 February 2007 Originating Service Group(s) REGENERATION AND ENVIRONMENT Contact Officer(s)/ STEPHEN ALEXANDER (Head of Development Control) Telephone Number(s) (01902) 555610 Title/Subject Matter APPLICATIONS DETERMINED UNDER OFFICER DELEGATION, WITHDRAWN, ETC. The attached Schedule comprises planning and other application that have been determined by authorised officers under delegated powers given by Committee, those applications that have been determined following previous resolutions of Planning Committee, or have been withdrawn by the applicant, or determined in other ways, as details. Each application is accompanied by the name of the planning officer dealing with it in case you need to contact them. The Case Officers and their telephone numbers are Wolverhampton (01902): Major applications Minor applications Other applications Ian Holiday 555630 Alan Murphy 555632 Martyn Gregory 551125 (Section Leader) (Section Leader) (Section Leader) Mizzy Marshall 551133 (Planning Officers) (Planning Officers) (Senior Planning Officer) Ken Harrop 555649 Tracey Homfray 555641 Jenny Davies 555608 Ragbir Sahota 555616 Richard Pitt 551674 Mindy Cheema 551360 Rob Hussey 551130 (Planning Officer) Phillip Walker 555632 Nussarat Malik 551132 John Somers 551134 Sarah Luxmoore 555602 Mark Elliot 555648 Joseph Bartley 555631 HEAD OF DEVELOPMENT CONTROL: STEPHEN ALEXANDER 555610 FAXES can be sent on 551359 or 558792 E-MAIL [email protected]