National and Provincial-Level Fertility Trends in Iran, 1972-2000

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Analysis of the Impact of Land Use Changes on Soil Erosion Intensity and Sediment Yield Using the Intero Model in the Talar Watershed of Iran

water Article Analysis of the Impact of Land Use Changes on Soil Erosion Intensity and Sediment Yield Using the IntErO Model in the Talar Watershed of Iran Maziar Mohammadi 1, Abdulvahed Khaledi Darvishan 1,* , Velibor Spalevic 2 , Branislav Dudic 3,4,* and Paolo Billi 5 1 Department of Watershed Management Engineering, Faculty of Natural Resources, Tarbiat Modares University, Noor 46417-76489, Iran; [email protected] 2 Department of Geography, Faculty of Philosophy, University of Montenegro, 81400 Niksic, Montenegro; [email protected] 3 Faculty of Management, Comenius University in Bratislava, 82005 Bratislava, Slovakia 4 Faculty of Economics and Engineering Management, University Business Academy, 21107 Novi Sad, Serbia 5 International Platform for Dryland Research and Education, Arid Land Research Center, Tottori University, Tottori 680-0001, Japan; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (A.K.D.); [email protected] (B.D.); Tel.: +98-9183795477 (A.K.D.) Abstract: Land use change is known as one of the main influencing factors on soil erosion and sediment production processes. The objective of the article is to study on how land use change impacts on soil erosion by using Intensity of Erosion and Outflow (IntErO) as a process-oriented Citation: Mohammadi, M.; Khaledi soil erosion model. The study has been conducted under land use changes within the period of Darvishan, A.; Spalevic, V.; Dudic, B.; 1991–2014 in the Talar watershed located in northern Iran. The GIS environment was used to prepare Billi, P. Analysis of the Impact of Land the required maps including Digital Elevation Model (DEM), geology, land use, soil, and drainage Use Changes on Soil Erosion Intensity network. -

Prevalence of Tobacco Mosaic Virus in Iran and Evolutionary Analyses of the Coat Protein Gene

Plant Pathol. J. 29(3) : 260-273 (2013) http://dx.doi.org/10.5423/PPJ.OA.09.2012.0145 The Plant Pathology Journal pISSN 1598-2254 eISSN 2093-9280 © The Korean Society of Plant Pathology Open Access Prevalence of Tobacco mosaic virus in Iran and Evolutionary Analyses of the Coat Protein Gene Athar Alishiri1, Farshad Rakhshandehroo1*, Hamid-Reza Zamanizadeh1 and Peter Palukaitis2 1Department of Plant Pathology, College of Agriculture and Natural Resources, Science and Research Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran 14515-775, Iran 2Department of Horticultural Sciences, Seoul Women’s University, Seoul 139-774, Korea (Received on September 13, 2012; Revised on February 7, 2013; Accepted on March 5, 2013) The incidence and distribution of Tobacco mosaic virus cantaloupe (Cucumis melo var. cantalupensis), courgettes (TMV) and related tobamoviruses was determined using (Cucurbita pepo L. cv. Zucchini), cucumber (Cucumis sativus an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay on 1,926 sympto- L.), melon (C. melo L.), pumpkin (Cucurbita moschata matic horticultural crops and 107 asymptomatic weed Duch.), watermelon (Citrullus lanatus var. lanatus) and samples collected from 78 highly infected fields in the winter squash (Cucurbita maxima Duch. ex Lam)], major horticultural crop-producing areas in 17 pro- eggplant (Solanum melongena L.), garlic (Allium sativum vinces throughout Iran. The results were confirmed by L.), green beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.), onion (Allium host range studies and reverse transcription-polymer- ase chain reaction. The overall incidence of infection by cepa L.), pepper (Capsicum annum L.), potato (Solanum these viruses in symptomatic plants was 11.3%. The tuberosum subsp. tuberosum), spinach (Spinacia oleraceae coat protein (CP) gene sequences of a number of isolates L.) and tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.). -

The State and Territorial Social Justice in Postrevolutionary Iran *

International Journal of Urban and Regional Research Volume 13, Number 1, March 1989 The state and territorial social justice in postrevolutionary Iran * by Hooshang Amirahmadi The Iranian revolution of 1979, which toppled the Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi's 38-year old regime and ended nearly 2500 years of monarchy in Iran. had three generally acknowledged objectives: democracy, national independence and social justice, The first of these objectives was directed against the Shah's dictatorship. the second against external dependency. and the third against the uneven development of capitalism in Iran, The Islamic leadership of the revolution convinced the people that their demands would best be realized in an Islamic government, Of the three objectives. only social justice is of interest here and that only to the extent that it relates to territorial social justice (TSJ), The term 'territory' is used interchangeably with province (Ostan) and refers to an administrative subdivision. used. primarily. as a tool for nominal geographic distribution of state power. political control and economic management, There are 24 such subdivisions in Iran, TSJ is defined to include economic. social. political. cultural and ideological relations within and among territories of a given nation. It encompasses territorial provision of basic needs. balanced interterrito- rial development and resource allocation on the basis of need and potential. territorial balance of political power and decentralization of development policies. popular participation in local administration and decision-making. and respect for cultural diversity and autonomy. The TSJ concept is. therefore. an obvious improvement over conceptions such as 'balance'. 'convergence'. and 'equity' being propagated in the literature on regional questions. -

Nitrate Content in Drinking Water in Gilan and Mazandaran Provinces

ntal & A me na n ly o t ir ic v a n l Ziarati et al., J Environ Anal Toxicol 2014, 4:4 T E o Journal of f x o i l c o a DOI: 10.4172/2161-0525.1000219 n l o r g u y o J Environmental & Analytical Toxicology ISSN: 2161-0525 ResearchResearch Article Article OpenOpen Access Access Nitrate Content in Drinking Water in Gilan and Mazandaran Provinces, Iran Parisa Ziarati1*, Tirdad Zendehdel2 and Sepideh Arbabi Bidgoli3 1Medicinal Chemistry Department, Pharmaceutical Sciences Branch, Islamic Azad University (IAUPS), Tehran, Iran 2Chemistry Department, Advanced Sciences & Technologies Faculty, Pharmaceutical Sciences Branch, Islamic Azad University (IAUPS), Tehran, Iran 3Pharmacology & Toxicology Department, Pharmaceutical Sciences Branch, Islamic Azad University (IAUPS), Tehran, Iran Abstract Water pollution issue has become one of the most important public awareness issues. The excessive use of the fertilizers and pesticides in agriculture with the threat of the chemicals in water and crops especially in the two north provinces of Iran is a major concern of Iranian environmental scientists. This project is a trial to find out the status of nitrate content in drinking water of two great provinces in the north of Iran. The objectives of the present research: Determination the level of nitrate (mg/L) in drinking water of some agricultural and industrial cities and comparing of the probable effects of different industrial factories on the level of nitrate in drinking water of them. The tap water samples of 60 different sites from Rasht , Bandar Anzali and Talesh in Gilan province and Sari, Behshar and Amol in Mazandaran province in three consequent months in summer season (July, August and September) in 2013, were collected and by spectroscopy method were determined. -

IRAN Flash Update As of 21 April 2020

ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF IRAN Flash Update As of 21 April 2020 Highlights • Islamic Republic of Iran is the eighth-worst affected country by COVID-19 in the world; Nearly 85,000 cases have been detected; 5,297 people have died; • Continuing floods and rising water level have caused extensive damage to the peoples’ livelihood and farm lands; four persons were killed, 50 people were rescued in the past week. Coronavirus COVID-19 Situation overview: Between 16 and 21 April, 8,413 new COVID-19 cases, including 520 deaths were confirmed in the Islamic Republic of Iran. This brings the cumulative to 84,802 cases detected with 5,297 deaths. In total, 59,273 patients have 5,297 recovered. The officially confirmed cases and deaths have decreased in the past week. Iran is, however, the deaths eighth-worst affected country in the world with increasing incidence reported in at least 8 of 31 provinces. The Iranian Government opened intercity highways and major shopping centres from 20 April to stimulate its economy. This is a part of the country’s ‘Smart Distancing Plan’ which has allowed the resumption of ‘low risk business’ from 11 April in all provinces except Tehran, and from 18 April in Tehran. Mosques and other religious places remain closed until 4 May while the month of Ramadan is expected to start from 23 April this year. Humanitarian impact/needs: On 20 April, the country’s traffic counting systems marked an increase of about 5.6 percent in traffic volume compared to the previous day. Overcrowded buses and metro wagons were observed. -

INSTITUTIONS, SOCIAL STATUS, and the PROVINCIAL DIVIDE in IRAN's ELECTORAL POLITICS a Dissertation

THE PARADOX OF PARTICIPATION: INSTITUTIONS, SOCIAL STATUS, AND THE PROVINCIAL DIVIDE IN IRAN'S ELECTORAL POLITICS A dissertation submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Alireza Raisi December 2016 Dissertation written by Alireza Raisi M.A., Kent State University, USA, 2013 B.S., Sharif University of Technology, Iran, 2000 Approved by _____Andrew Barnes________________________ , Chair, Doctoral Dissertation Committee _____Landon Hancock______________________ , Members, Doctoral Dissertation Committee _____Daniel Hawes______________________________ _____Mary Ann Heiss____________________________ _____David Kaplan______________ _______________ Accepted by _____Andrew Barnes__________________________ , Chair, Department of Political Science ______James Blank_____________________________ , Dean, College of Arts and Sciences ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES……………………………………………………………………………iv LIST OF TABLES……………………………………………………………………………...v ACKNOWLEDGMENT……………………………………………………………………...vi CHAPTER1 ........................................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 1 CHAPTER2 ......................................................................................................................................... 19 The Rise of Clientelism in Parliamentary -

Differential Mortality in Iran

Differential mortality in Iran Background Among the available data provided by health information systems, data on mortality are commonly used not only as health indicators but also as socioeconomic development indices. Recognizing that in Iran accurate data on causes of death were not available, the Deputy of Health in the Ministry of Health and Medical Education (MOH&ME) established a new comprehensive system for death registration which started in one province (Bushehr) as a pilot in 1997, and was subsequently expanded to include all other provinces, except Tehran province. These data can be used to investigate the nature and extent of differences in mortality in Iran. The objective of this paper is to estimate provincial differences in the level of mortality using this death registration system. Methods Data from the death registration system for 2004 for each province were evaluated for data completeness, and life tables were created for provinces after correction for under-enumeration of death registration. For those provinces where it was not possible to adjust the data on adult deaths by using the Brass Growth Balance method, adult mortality was predicted based on adult literacy using information from provinces with reliable data. Results Child mortality (risk of a newborn dying before age 5, or 5q0) in 2004 varied between 47 per 1000 live births for both sexes in Sistan and Baluchistan province, and 25 per 1000 live births in Tehran and Gilan provinces. For adults, provincial differences in mortality were much greater for males than females. Adult mortality (risk of dying between ages 15 and 60, or 45q15) for females varied between 0.133 in Kerman province and 0.117 in Tehran province; for males the range was from 0.218 in Kerman to 0.149 in Tehran province. -

13836 Thursday DECEMBER 17, 2020 Azar 27, 1399 Jumada Al Awwal 2, 1442 Iran Voices CAS Rejects Appeal Indonesia Leader’S Book “Islamic Concern Over U.S

WWW.TEHRANTIMES.COM I N T E R N A T I O N A L D A I L Y 8 Pages Price 50,000 Rials 1.00 EURO 4.00 AED 42nd year No.13836 Thursday DECEMBER 17, 2020 Azar 27, 1399 Jumada Al Awwal 2, 1442 Iran voices CAS rejects appeal Indonesia Leader’s book “Islamic concern over U.S. over Alekasir’s ban denies in talks Thought in the Quran” nuclear tests Page 2 in ACL final Page 3 with Israel Page 5 published in Urdu Page 8 Rouhani says happy over Trump’s leaving, but ‘not excited’ over Biden’s coming TEHRAN – President Hassan Rouhani He described Trump as a person has said his administration is “not ex- who even blocked the provision of cited” about U.S. President-elect Joe vaccines to patients because he did Biden’s victory, but it’s happy about the not adhere to any moral and humane defeat of Donald Trump. principles. Clear “Some say you are excited about The remarks came two days after the Biden’s coming [into power]. No, we’re U.S. Electoral College voted to confirm no excited, but we’re very happy about the final electoral result of 306 to 232 Trump’s leaving,” Rouhani said at a in favor of Biden. cabinet meeting on Wednesday. Continued on page 2 message ICCIMA offers suggestions to amend next year’s budget bill TEHRAN – Iran Chamber of Commerce, that the budget bill is important to them Industries, Mines, and Agriculture (ICCI- from two perspectives: the impact of the Ayatollah Khamenei urges MA) Research Center, after examining the budget on macroeconomic variables and strengths and weaknesses of the budget bill its impact on the business environment. -

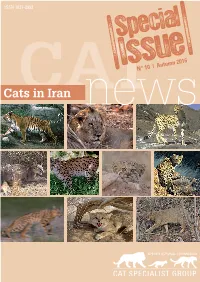

The Caracal in Iran - Current State of Knowledge and Pri- Orities for Conservation

ISSN 1027-2992 I Special Issue I N° 10 | Autumn 2016 CatsCAT in Iran news 02 CATnews is the newsletter of the Cat Specialist Group, a component Editors: Christine & Urs Breitenmoser of the Species Survival Commission SSC of the International Union Co-chairs IUCN/SSC for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). It is published twice a year, and is Cat Specialist Group available to members and the Friends of the Cat Group. KORA, Thunstrasse 31, 3074 Muri, Switzerland For joining the Friends of the Cat Group please contact Tel ++41(31) 951 90 20 Christine Breitenmoser at [email protected] Fax ++41(31) 951 90 40 <[email protected]> Original contributions and short notes about wild cats are welcome Send <[email protected]> contributions and observations to [email protected]. Guidelines for authors are available at www.catsg.org/catnews Cover Photo: From top left to bottom right: Caspian tiger (K. Rudloff) This Special Issue of CATnews has been produced with support Asiatic lion (P. Meier) from the Wild Cat Club and Zoo Leipzig. Asiatic cheetah (ICS/DoE/CACP/ Panthera) Design: barbara surber, werk’sdesign gmbh caracal (M. Eslami Dehkordi) Layout: Christine Breitenmoser & Tabea Lanz Eurasian lynx (F. Heidari) Print: Stämpfli Publikationen AG, Bern, Switzerland Pallas’s cat (F. Esfandiari) Persian leopard (S. B. Mousavi) ISSN 1027-2992 © IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group Asiatic wildcat (S. B. Mousavi) sand cat (M. R. Besmeli) jungle cat (B. Farahanchi) The designation of the geographical entities in this publication, and the representation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Estimating Child Mortality Rate and Its Trend in Hamadan Province, Western Iran from 1990 to 2016: Implications for Sustainable Development Goal

JRHS 2018; 18(1): e00407 JRHS Journal of Research in Health Sciences journal homepage: www.umsha.ac.ir/jrhs Original Article Estimating Child Mortality Rate and its Trend in Hamadan Province, Western Iran from 1990 to 2016: Implications for Sustainable Development Goal Younes Mohammadi (PhD)1,2, Rashid Heidarimoghadam (MD)3, Bistoon Hosseini (PhD)4, Mohammad Babamiri (PhD)5, Azita Nikravesh (MSc)6, Masoumeh Javaheri (MSc)7*, Babak Moeini (PhD)5 1 Modeling of Noncommunicable Disease Research Center, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran 2 Department of Epidemiology, School of Public Health, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran 3 Research Center for Health Sciences, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran 4 Kermanshah Province Electricity Distribution Company, Kermanshah, Iran 5 Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran 6 Deputy of Social Affairs, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran 7 Deputy of Health, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran ARTICLE INFORMATION ABSTRACT Article history: Background: Child mortality is one of the major health indices and the main targets in sustainable Received: 03 January 2018 development goals. This study aimed to estimate child mortality rate and assess the progress toward Revised: 17 February 2018 sustainable development goals in Hamadan Province, western Iran and its districts from 1990 to 2016. Accepted: 26 February 2018 Study design: A cross-sectional study. Available online: 07 March 2018 Methods: We used two data sources including death registration system (DRS) and summary birth history Keywords: data (SBH) of 2010 census for estimating child mortality rate. SBH data was analyzed by Maternal Age Infant mortality/trend Cohort and Maternal age period methods. -

And 'Ethnicity'

ABSTRACT MELLAT AND QOWM: A POLITICAL GEOGRAPHY OF ‘NATION’ AND ‘ETHNICITY’ IN IRAN by Sanan Moradi This thesis examines the Iranian state’s policies towards its ethnic minority regions. The thesis attempts to explain how categories of ‘nation’ and ‘ethnicity’ are constructed as ‘mellat’ and ‘qowm’ through dominant political discourses. Afterwards, the thesis demonstrates how such categories have influenced state’s policies of economic development. The thesis argues that the state has long avoided developing ethnic minority regions, due to perceiving such regions as “unsafe”. Over decades, aversion in developing ethnic minority peripheral provinces, and prioritizing Persian-Shiite majority central parts of the country, has created an internal core- periphery pattern of economic (under)development. Finally, the thesis speculates, this pattern of economic development has influenced interprovincial migration patterns, in a way that populations migrate from underdeveloped ethnic minority periphery to developed Persian-Shiite majority core. Such migration patterns could pave the way for population mixing, and possibly cultural assimilation. MELLAT AND QOWM A POLITICAL GEOGRAPHY OF ‘NATION’ AND ‘ETHNICITY’ IN IRAN A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University In partial fulfillment of The requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Geography by Sanan Moradi Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2014 Advisor________________________ (Dr. Carl Dahlman) Reader_________________________ (Dr. Stanley Toops) Reader_________________________ (Dr. Neringa Klumbyte) Table of Contents List of Tables iv List of Maps v Acknowledgements vi Chapter 1: Introduction 1 1.1 Introduction 1 1.2 Summary of Chapters 2 Chapter 2: Study Area 4 2.1 Introduction 4 2.2 From Empire to State; a Brief History of Iran 4 2.2.1Safavid 4 2.2.2 Qajar 4 2.2.3 Pahlavi 5 2.2.4 The Islamic Republic 6 2.3 Physical Terrain 7 2.4 Ethnic Minorities of Iran; an Overview 8 2.4.1 Azeri 10 2.4.2 Kurd 12 2.4.3 Arab 15 2.4.4 Baluch 16 2.5 Conclusion 18 Chapter 3: Conceptual Framework 19 3.1. -

Iran Is More Than Persia Ethnic Politics in the Islamic Republic

Iran Is More Than Persia Ethnic Politics in the Islamic Republic Brenda Shaffer Foreword by Reuel Marc Gerecht April 2021 FOUNDATION FOR DEFENSE OF DEMOCRACIES Iran Is More Than Persia Ethnic Politics in the Islamic Republic Brenda Shaffer Foreword by Reuel Marc Gerecht April 2021 FDD PRESS A division of the FOUNDATION FOR DEFENSE OF DEMOCRACIES Washington, DC Iran Is More Than Persia: Ethnic Politics in the Islamic Republic Table of Contents FOREWORD ......................................................................................................................................... 6 INTRODUCTION: WHY ETHNICITY IN IRAN IS IMPORTANT ............................................... 7 Tehran Knows .......................................................................................................................................................8 DEMOGRAPHY .................................................................................................................................... 9 Iran’s Ethnic Groups .............................................................................................................................................10 Iran by the Numbers ............................................................................................................................................12 THE ISLAMIC REPUBLIC’S POLICIES TOWARD ETHNIC MINORITIES ................................. 19 Use of Ethnic Minority Languages in Schools and Official Settings .............................................................20 Incarceration