Iranian Azerbaijanis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Toponimys with Ancient Turk Origins in the Balkans

IBAC 2012 vol.2 TOPONIMYS WITH ANCIENT TURK ORIGINS IN THE BALKANS Prof .Ass. Hajiyeva GALIBA Nakhchivan State Univresity, e-mail: [email protected] Abstract One of the sources dealing with the ancient Turkic history are toponyms. Toponymic investigations show that most of the ancient geographical names which have spread in Eurosia, in Central Asia, from North Africa, to Eastern Turkistan even in Siberia and these names were formed before Roman and Byzantine periods. So development of toponymic investigations, study of the history of Turkic peoples and scientific investigation of existing geographical names which keep the history of Turkic peoples have great significance. One of the uninvestigated fields of the Turkic history are geographical names keeping historical facts within are the holy Balkan areas. The toponymic investigations carried on the Balkans show that these territories are the places were the ancient Turkic tribes were firstly settled and possessed. This fact is proved by the Turkic tribe names and by the words of different semantic meaning of the languages of Turkic tribes. The great deal of Balkan geographical names are the names derived out of ethnoniyms thus the names reflecting ancient Turkic tribe names (Astipos//Astepe//Ishtip, Izletdere, Vardar, Sofular, Gilan, Sahsuvar kariyesi, Kosalar village, Tatarli kariyesi, in the Kosova, Uskup, Usturumca, Kumanova, Propishtip, Kochana, Makedonska Kamenika in Makedony, Araz district, Arazli, Azman, Cepine, Coban, Chorlu, Culfalar, Horozlar, Kangirlar, Sakarli, Sungurlar, Karuk, Kaspi, Kaz//Kas, Kazancilar, Kecililer, Kuman, Padarlar, Sofular, Tatar, Uzlar in Bulgaria) show that Balkans historically were Turkic areas. Geographical names are the real witnesses of history. We must pay great attention to the scientific investigations of the geographical names in Balkan states. -

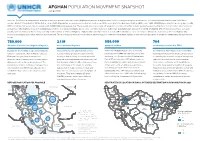

IRN Population Movement Snapshot June 2021

AFGHAN POPULATION MOVEMENT SNAPSHOT June 2021 Since the 1979 Soviet invasion and the subsequent waves of violence that have rocked Afghanistan, millions of Afghans have fled the country, seeking safety elsewhere. The Islamic Republic of Iran boasts 5,894 km of borders. Most of it, including the 921 km that are shared with Afghanistan, are porous and located in remote areas. While according to the Government of Iran (GIRI), some 1,400-2,500 Afghans arrive in Iran every day, recently GIRI has indicated increased daily movements with 4,000-5,000 arriving every day. These people aren’t necesserily all refugees, it is a mixed flow that includes people being pushed by the lack of economic opportunities as well as those who might be in need of international protection. The number fluctuates due to socio-economic challenges both in Iran and Afghanistan and also the COVID-19 situation. UNHCR Iran does not have access to border points and thus is unable to independently monitor arrivals or returns of Afghans. Afghans who currently reside in Iran have dierent statuses: some are refugees (Amayesh card holders), other are Afghans who posses a national passport, while other are undocumented. These populations move across borders in various ways. it is understood that many Afghans in Iran who have passports or are undocumented may have protection needs. 780,000 2.1 M 586,000 704 Amayesh Card Holders (Afghan refugees1) undocumented Afghans passport holders voluntarily repatriated in 2021 In 2001, the Government of Iran issues Amayesh Undocumented is an umbrella term used to There are 275,000 Afghans who hold family Covid-19 had a clear impact on the low VolRep cards to regularize the stay of Afghan refugees. -

KHAZAR UNIVERSITY Faculty

KHAZAR UNIVERSITY Faculty: Education Major: General and Applied Linguistics Topic: “May your young people cast off the stone of singleness:” Azerbaijani “alqış phrases” (blessing formulas) and their American English equivalents, or what is revealed by the lack thereof Master student: Martha Lawry Scientific Advisor: Professor Hamlet Isaxanli Submitted January 2012 1 Summary This thesis by Martha Lawry is entitled “„may your young people cast off the stone of singleness:‟ Azerbaijani „alqış phrases‟ (blessing formulas) and their American English equivalents, or what is revealed by the lack thereof.” The objective of the research is to define the alqış phrases which are frequently used in modern spoken Azerbaijani, determine how best to define them in English, determine their linguistic functions in Azerbaijani, and compare them to the phrases that most closely fulfill the same functions in American English. Ethnographic and comparative research methods were used, including reviewing secondary sources (literature reviews) and qualitative research in the form of both semi- structured interviews conducted with native Azerbaijani speakers of varying ages and social strata living in the Azerbaijan Republic and open-ended structured interviews conducted via an online questionnaire with native English speakers living in the United States. The research led to the conclusion that alqış phrases should be defined as ―blessing formulas‖ in English. Most alqış phrases were determined to be grammatically distinguished by second or third person verbs in optative or imperative mood. They can have the expressive functions of being bono-recognitive, bono-petitive, malo-recognitive or malo-fugitive, although the most common are bono-petitive and malo-fugitive. Alqış phrases were also shown to be politeness strategies according to Levinson and Brown‘s politeness theory (used to protect the speaker‘s positive face or to protect the listener‘s negative face). -

CAUCASUS ANALYTICAL DIGEST No. 86, 25 July 2016 2

No. 86 25 July 2016 Abkhazia South Ossetia caucasus Adjara analytical digest Nagorno- Karabakh www.laender-analysen.de/cad www.css.ethz.ch/en/publications/cad.html TURKISH SOCIETAL ACTORS IN THE CAUCASUS Special Editors: Andrea Weiss and Yana Zabanova ■■Introduction by the Special Editors 2 ■■Track Two Diplomacy between Armenia and Turkey: Achievements and Limitations 3 By Vahram Ter-Matevosyan, Yerevan ■■How Non-Governmental Are Civil Societal Relations Between Turkey and Azerbaijan? 6 By Hülya Demirdirek and Orhan Gafarlı, Ankara ■■Turkey’s Abkhaz Diaspora as an Intermediary Between Turkish and Abkhaz Societies 9 By Yana Zabanova, Berlin ■■Turkish Georgians: The Forgotten Diaspora, Religion and Social Ties 13 By Andrea Weiss, Berlin ■■CHRONICLE From 14 June to 19 July 2016 16 Research Centre Center Caucasus Research German Association for for East European Studies for Security Studies Resource Centers East European Studies University of Bremen ETH Zurich CAUCASUS ANALYTICAL DIGEST No. 86, 25 July 2016 2 Introduction by the Special Editors Turkey is an important actor in the South Caucasus in several respects: as a leading trade and investment partner, an energy hub, and a security actor. While the economic and security dimensions of Turkey’s role in the region have been amply addressed, its cross-border ties with societies in the Caucasus remain under-researched. This issue of the Cauca- sus Analytical Digest illustrates inter-societal relations between Turkey and the three South Caucasus states of Arme- nia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia, as well as with the de-facto state of Abkhazia, through the prism of NGO and diaspora contacts. Although this approach is by necessity selective, each of the four articles describes an important segment of transboundary societal relations between Turkey and the Caucasus. -

A Brief Overview on Karabakh History from Past to Today

Volume: 8 Issue: 2 Year: 2011 A Brief Overview on Karabakh History from Past to Today Ercan Karakoç Abstract After initiation of the glasnost (openness) and perestroika (restructuring) policies in the USSR by Mikhail Gorbachev, the Soviet Union started to crumble, and old, forgotten, suppressed problems especially regarding territorial claims between Azerbaijanis and Armenians reemerged. Although Mountainous (Nagorno) Karabakh is officially part of Azerbaijan Republic, after fierce and bloody clashes between Armenians and Azerbaijanis, the entire Nagorno Karabakh region and seven additional surrounding districts of Lachin, Kelbajar, Agdam, Jabrail, Fizuli, Khubadly and Zengilan, it means over 20 per cent of Azerbaijan, were occupied by Armenians, and because of serious war situations, many Azerbaijanis living in these areas had to migrate from their homeland to Azerbaijan and they have been living under miserable conditions since the early 1990s. Keywords: Karabakh, Caucasia, Azerbaijan, Armenia, Ottoman Empire, Safavid Empire, Russia and Soviet Union Assistant Professor of Modern Turkish History, Yıldız Technical University, [email protected] 1003 Karakoç, E. (2011). A Brief Overview on Karabakh History from Past to Today. International Journal of Human Sciences [Online]. 8:2. Available: http://www.insanbilimleri.com/en Geçmişten günümüze Karabağ tarihi üzerine bir değerlendirme Ercan Karakoç Özet Mihail Gorbaçov tarafından başlatılan glasnost (açıklık) ve perestroyka (yeniden inşa) politikalarından sonra Sovyetler Birliği parçalanma sürecine girdi ve birlik coğrafyasındaki unutulmuş ve bastırılmış olan eski problemler, özellikle Azerbaycan Türkleri ve Ermeniler arasındaki sınır sorunları yeniden gün yüzüne çıktı. Bu bağlamda, hukuken Azerbaycan devletinin bir parçası olan Dağlık Karabağ bölgesi ve çevresindeki Laçin, Kelbecer, Cebrail, Agdam, Fizuli, Zengilan ve Kubatlı gibi yedi semt, yani yaklaşık olarak Azerbaycan‟ın yüzde yirmiye yakın toprağı, her iki toplum arasındaki şiddetli ve kanlı çarpışmalardan sonra Ermeniler tarafından işgal edildi. -

Nationalism, Politics, and the Practice of Archaeology in the Caucasus

-.! r. d, J,,f ssaud Artsus^rNn Mlib scoIuswVC ffiLffi pac,^^€C erplJ pue lr{o) '-I dlllqd ,iq pa11pa ,(8oyoe er4lre Jo ecr] JeJd eq] pue 'sct1t1od 'tustleuolleN 6rl Se]tlJlljd 18q1 uueul lOu soop sltll'slstSo[ocPqJJu ul?lsl?JneJ leool '{uetuJO ezrsuqdtue ol qsl'\\ c'tl'laslno aql 1V cqtJo lr?JttrrJ Suteq e:u e,\\ 3llLl,\\'ieqt 'teqlout? ,{g eldoed .uorsso.rciclns euoJo .:etqSnr:1s louJr crleuols,{s eql ul llnseJ {eru leql tsr:d snolJes uoJl uPlseJnPJ lerll JO suoluolstp :o ..sSutpucJsltu,' "(rolsrqerd '..r8u,pn"r.. roJ EtlotlJr qsllqulso ol ]duralltl 3o elqetclecctl Surqsrn8urlstp o.1". 'speecorcl ll sV 'JB ,(rnluec qlxls-pltu eql ut SutuutSeq'et3:oe9 11^ly 'porred uralse,t\ ut uotJl?ztuolol {eer{) o1 saleleJ I se '{1:clncrlled lBJlsselc uP qil'\\ Alluclrol eq] roJ eJueptlc 1r:crSoloaeqcJe uuts11311l?J Jo uollRnlele -ouoJt-loueqlpue-snseon€JuJequoueqlpuE'l?luoulJv'er8rocg'uelteq -JaZVulpJosejotrolsrqerdsqtJoSuouE}erdlelutSutreptsuoc.,{11euor8ar lsrgSurpeeco:cl'lceistqlsulleJlsnlpselduexalere^esButlele;"{qsnsecne3 reded stql cql ur .{SoloeeqJlu Jo olnlpu lecrllod eql elBltsuotuop [lt,\\ .paluroclduslp lou st euo 'scrlr1od ,(:erodueluoJ o1 polelsJUtr '1tns:nd JturcpeJe olpl ue aq or ,{Soloeuqole 3o ecrlcu'rd eq} lcedxa lou plno'{\ 'SIJIUUOC aAISOldxe ouo 3Jor{,t\ PoJe uP sl 1t 'suolllpuoJ aseql IIe UsAtD sluqle pur: ,{poolq ,{11euor1dacxo lulo^es pue salndstp lelrollrrel snor0tunu qlr,n elalder uot,3e; elllBlo^ ,(re,r. e st 1l 'uolun lel^os JeuIJoJ aql io esdelloc eqt ue,tr.3 'snsBsnBJ aql jo seldoed peu'{u oql lle ro3 ln3Sutueau 'l?Iuusllllu -

Asala & ARF 'Veterans' in Armenia and the Nagorno-Karabakh Region

Karabakh Christopher GUNN Coastal Carolina University ASALA & ARF ‘VETERANS’ IN ARMENIA AND THE NAGORNO-KARABAKH REGION OF AZERBAIJAN Conclusion. See the beginning in IRS- Heritage, 3 (35) 2018 Emblem of ASALA y 1990, Armenia or Nagorno-Karabakh were, arguably, the only two places in the world that Bformer ASALA terrorists could safely go, and not fear pursuit, in one form or another, and it seems that most of them did, indeed, eventually end up in Armenia (36). Not all of the ASALA veterans took up arms, how- ever. Some like, Alex Yenikomshian, former director of the Monte Melkonian Fund and the current Sardarapat Movement leader, who was permanently blinded in October 1980 when a bomb he was preparing explod- ed prematurely in his hotel room, were not capable of actually participating in the fighting (37). Others, like Varoujan Garabedian, the terrorist behind the attack on the Orly Airport in Paris in 1983, who emigrated to Armenia when he was pardoned by the French govern- ment in April 2001 and released from prison, arrived too late (38). Based on the documents and material avail- able today in English, there were at least eight ASALA 48 www.irs-az.com 4(36), AUTUMN 2018 Poster of the Armenian Legion in the troops of fascist Germany and photograph of Garegin Nzhdeh – terrorist and founder of Tseghakronism veterans who can be identified who were actively en- tia group of approximately 50 men, and played a major gaged in the conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh (39), but role in the assault and occupation of the Kelbajar region undoubtedly there were more. -

Sheikh Safi Al-Din Ensemble in Ardabil

Weaver, M.E., Preliminary study on the conservation problems of five Iranian monuments, UNESCO, Paris, 1970. Sheikh Safi al-Din Ensemble in Weaver, M.E., Iran. The conservation of the Shrine of Sheik Safi Ardabil (Iran) at Ardabil: second preliminary study July-August 1971, No 1345 UNESCO, Paris, 1971. Technical Evaluation Mission: 18-22 October 2009 Additional information requested and received from the Official name as proposed by the State Party: State Party: A letter was sent to the State Party on 15 December 2009, requesting the following: Sheikh Safi al-Din Khānegāh and Shrine Ensemble in Ardabil • Information about the timeframe for the approval and implementation of the Ardabil Master Plan; Location: • Description of how the provisions for the core, buffer, and landscape zones relate to the Master Province of Ardabil Plan; Islamic Republic of Iran • Further information on the structure and implementation of the Management Plan for the Brief description: nominated property; • Progress on the implementation without delay of The Sheik Safi al-Din Khānegāh and Shrine Ensemble in ICHHTO’s plans to relocate the brick workshop; Ardabil was built as a microcosmic city of bazaars, public • Detailed information about the underground baths and squares, religious facilities, houses, and multi-level parking which is being built to the west offices. It was the largest khānegāh (Sufic place for of the museum and related measures to mitigate spiritual retreat) in Iran. During the reigns of the Safavid impact on the nominated property; rulers, this ensemble was of special political and national • Steps being taken to develop a Landscape Plan significance as the most prominent shrine of the founder for the entire nominated property; of the dynasty. -

Oct. 6-12, 2020 Further Reproduction Or Distribution Is Subject to Original Copyright Restrictions

Weekly Media Report –Oct. 6-12, 2020 Further reproduction or distribution is subject to original copyright restrictions. ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..…… EDUCATION: 1. Marine Corps’ Landmark PhD Program Celebrates First Technical Graduate (Marines.mil 7 Oct 20) (Navy.mil 7 Oct 20) (NPS.edu 7 Oct 20) (Military Spot 12 Oct 20) … Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Taylor Vencill When the Marine Corps developed its new Doctor of Philosophy Program (PHDP), the service recognized the need for a cohort of strategic thinkers and technical leaders capable of the applied research and innovative thinking necessary to develop warfighter advantage in the modern, cognitive age. The Technical version of the program, PHDP-T, just celebrated its first graduate, with Maj. Ezra Akin completing his doctorate in operations research from the Naval Postgraduate School (NPS), Sept. 25. INDUSTRY PARTNERS: 2. Denver Startup Kayhan Space Lands $600k Seed Round for Collision Avoidance Software (ColoradoInno 6 Oct 20) … Nick Greenhalgh Much like on city streets, space traffic can be hectic and near misses are becoming all too common. Just last year, an in-orbit European Space Agency satellite was forced to perform an evasive maneuver to avoid a collision with a SpaceX satellite. Kayhan Space currently provides satellite collision assessment and avoidance support to the Naval Postgraduate School and BlackSky missions. FACULTY: 3. Will Armenia and Azerbaijan Fight to the Bitter End? [AUDIO INTERVIEW] (English News Highlights 5 Oct 20) Armenia and Azerbaijan accuse each other of attacking civilian areas as the deadliest fighting in the South Caucasus region for more than 25 years continues. KAN's Mark Weiss spoke with South Caucasus expert Brenda Shaffer, formerly a professor at Haifa University and now at the US Navy Postgraduate University. -

3. Energy Reserves, Pipeline Routes and the Legal Regime in the Caspian Sea

3. Energy reserves, pipeline routes and the legal regime in the Caspian Sea John Roberts I. The energy reserves and production potential of the Caspian The issue of Caspian energy development has been dominated by four factors. The first is uncertain oil prices. These pose a challenge both to oilfield devel- opers and to the promoters of pipelines. The boom prices of 2000, coupled with supply shortages within the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), have made development of the resources of the Caspian area very attractive. By contrast, when oil prices hovered around the $10 per barrel level in late 1998 and early 1999, the price downturn threatened not only the viability of some of the more grandiose pipeline projects to carry Caspian oil to the outside world, but also the economics of basic oilfield exploration in the region. While there will be some fly-by-night operators who endeavour to secure swift returns in an era of high prices, the major energy developers, as well as the majority of smaller investors, will continue to predicate total production costs (including carriage to market) not exceeding $10–12 a barrel. The second is the geology and geography of the area. The importance of its geology was highlighted when two of the first four international consortia formed to look for oil in blocks off Azerbaijan where no wells had previously been drilled pulled out in the wake of poor results.1 The geography of the area involves the complex problem of export pipeline development and the chicken- and-egg question whether lack of pipelines is holding back oil and gas pro- duction or vice versa. -

The Effects of Nationalism on Territorial Integrity Among Armenians and Serbs Nina Patelic

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2008 The Effects of Nationalism on Territorial Integrity Among Armenians and Serbs Nina Patelic Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES THE EFFECTS OF NATIONALISM ON TERRITORIAL INTEGRITY AMONG ARMENIANS AND SERBS By Nina Patelic A Thesis submitted to the Department of International Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2008 The members of the Committee approve the thesis of Nina Pantelic, defended on September 28th, 2007. ------------------------------- Jonathan Grant Professor Directing Thesis ------------------------------- Peter Garretson Committee Member ------------------------------- Mark Souva Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii ACKOWLEDGEMENTS This paper could not have been written without the academic insight of my thesis committee members, as well as Dr. Kotchikian. I would also like to thank my parents Dr. Svetlana Adamovic and Dr. Predrag Pantelic, my grandfather Dr. Ljubisa Adamovic, my sister Ana Pantelic, and my best friend, Jason Wiggins, who have all supported me over the years. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………..v INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………………………….1 1. NATIONALISM, AND HOW IT DEVELOPED IN SERBIA AND ARMENIA...6 2. THE CONFLICT OVER KOSOVO AND METOHIJA…………………………...27 3. THE CONFLICT OVER NAGORNO KARABAKH……………………………..56 CONCLUSION………………………………………………………………...……….89 SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY…………………………………………………………93 BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH………………………………………………………….101 iv ABSTRACT Nationalism has been a driving force in both nation building and in spurring high levels of violence. As nations have become the norm in modern day society, nationalism has become detrimental to international law, which protects the powers of sovereignty. -

Russia's Migration Experience Pdf 0.52 MB

Valdai Papers #97 From Mistrust to Solidarity or More Mistrust? Russia’s Migration Experience in the International Context Dmitry Poletaev valdaiclub.com #valdaiclub December, 2018 About the Author Dmitry Poletaev Leading researcher at the Institute of Economic Forecasting of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Director of Migration Research Center This publication and other papers are available on http://valdaiclub.com/a/valdai-papers/ The views and opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not represent the views of the Valdai Discussion Club, unless explicitly stated otherwise. © The Foundation for Development and Support of the Valdai Discussion Club, 2018 42 Bolshaya Tatarskaya st., Moscow, 115184, Russia From Mistrust to Solidarity or More Mistrust? Russia’s Migration Experience in the International Context 3 The ease of transportation and communication in the modern world makes it possible to quickly deliver potential migrants to countries that they previously could only see on their television screens, hear about from family and friends living and working there, or read about in glossy magazines. A new era has dawned, different from anything humanity has ever experienced, and as the world becomes increasingly open to migration, the seeming simplicity of changing status, workplace and place of residence becomes all the more tempting. Unfortunately, ‘migration without borders’,1 once regarded as a promising strategy for the future, is increasingly viewed an undesirable outcome by a signifi cant number of people in host countries, and migrants can expect to fi nd solidarity mainly among fellow migrants and left-wing parties. Freedom of movement and freedom to choose a place of residence can be ranked among the category of freedoms which, as part of the Global Commons, have been restricted to varying degrees at the level of communities, states, and international associations.