Evangelical Review of Theology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The HARVEST FIELD

The HARVEST FIELD AUGUST, 189 7. ORIGINAL ARTICLES. A PLEASANT EPISODE. THE SNAKE-BITTEN HINDU’S GBATITUDE. BY THE EEV. JACOB CHAMBERLAIN, M.D. A M up on a little mountain in our mission district fifteen miles from Madanapalle. It stands 1,750 feet above the Madanapalle plain, and is, in the hot season, some ten degrees cooler. I have built here a little “ Hermitage” to which I can come for quiet literary work. The brain works more satisfactorily andrapidly with the lower temperature, and with the absence of the continual interruptions, to which the missionary at his own station is perpetually subject. Driving out to the foot of the mountain very early Monday morning, and climbing up the rough crooked path to the summit soon after sunrise, I can have five clear days with my aman uensis for my work in helping to prepare Telugu Christian literature for the growing native church, and go down „again Friday evening to have Saturday and Sunday at my station for other duties. Thus I am up here n o w ; but my usual isolation was interrupted one day last week by a very pleasing incident. 282 A PLEASANT EPISODE. I was sitting at my desk writing and glancing out upon the moun tain scenery, when, in the wide open doorway, a figure appeared, and looking up, I saw a man from one of our native Christian villages ten miles beyond this, who, with salaams and enquiries for my health, told me that he had come as the escort of a well-to-do high-caste Telugu landholder, who lived in the caste village adjacent to theirs, and who had come up to render his thanks to me for saving his life when he was a lad and had been bitten by a deadly serpent: would I be pleased to give him audience ? He was waiting in the adjoining clump of trees to know whether I could receive him now. -

The Ideological Differences Between Moderates and Extremists in the Indian National Movement with Special Reference to Surendranath Banerjea and Lajpat Rai

1 The Ideological Differences between Moderates and Extremists in the Indian National Movement with Special Reference to Surendranath Banerjea and Lajpat Rai 1885-1919 ■by Daniel Argov Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, in the University of London* School of Oriental and African Studies* June 1964* ProQuest Number: 11010545 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11010545 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 2 ABSTRACT Surendranath Banerjea was typical of the 'moderates’ in the Indian National Congress while Lajpat Rai typified the 'extremists'* This thesis seeks to portray critical political biographies of Surendranath Banerjea and of Lajpat Rai within a general comparative study of the moderates and the extremists, in an analysis of political beliefs and modes of political action in the Indian national movement, 1883-1919* It attempts to mirror the attitude of mind of the two nationalist leaders against their respective backgrounds of thought and experience, hence events in Bengal and the Punjab loom larger than in other parts of India* "The Extremists of to-day will be Moderates to-morrow, just as the Moderates of to-day were the Extremists of yesterday.” Bal Gangadhar Tilak, 2 January 190? ABBREVIATIONS B.N.]T.R. -

Jird Issue 7 Svh 08 15 11 3

A forum for academic, social, and timely issues affecting religious communities around the world. The Journal of InterReligious Dialogue Issue 7 August 2011 www.irdialogue.org 1 To submit an article visit www.irdialogue.org/submissions A forum for academic, social, and timely issues affecting religious communities around the world. Editorial Board Stephanie VarnonHughes and Joshua Zaslow Stanton, Editors‐in‐Chief Aimee Upjohn Light, Executive Editor Matthew Dougherty, Publishing Editor Sophia Khan, Associate Publishing Editor Christopher Stedman, Managing Director of State of Formation Ian Burzynski, Associate Director of State of Formation Editorial Consultants Frank Fredericks, Media Consultant Marinus Iwuchukwu, Outreach Consultant Stephen Butler Murray, Managing Editor Emeritus www.irdialogue.org 2 To submit an article visit www.irdialogue.org/submissions A forum for academic, social, and timely issues affecting religious communities around the world. Board of Scholars and Practitioners Y. Alp Aslandogan, President, Institute of Interfaith Dialog Justus Baird, Director of the Center for Multifaith Education, Auburn Theological Seminary Alan Brill, Cooperman/Ross Endowed Professor in honor of Sister Rose Thering, Seton Hall University Tarunjit Singh Butalia, Chair of Interfaith Committee, World Sikh Council - America Region Reginald Broadnax, Dean of Academic Affairs, Hood Theological Seminary Thomas Cattoi, Assistant Professor of Christology and Cultures, Jesuit School of Theology at Berkeley/Graduate Theological Union Miriam Cooke, -

1. Telegram to Mahomed Ali 2. Telegram to Basanti Devi

1. TELEGRAM TO MAHOMED ALI KHULNA, [June 17, 1925] REGARDING DELHI TROUBLE1 WANT SAY NOTHING ON MERITS. HAVE FULLEST FAITH YOUR INTEGRITY AND GODLINESS. MAY HE GUIDE US ALL. GANDHI From a photostat : S.N. 10644 2. TELEGRAM TO BASANTI DEVI DAS 2 [KHULNA, June 17, 1925 ] BASANTI DEVI DAS STEPASIDE DARJEELING MY HEART WITH YOU. MAY GOD BLESS YOU. EXPECT YOU BE BRAVE. BABY3 MUST NOT OVERGRIEVE. REACHING CALCUTTA EVENING. GANDHI From a photostat : S.N. 10644 3. TELEGRAM TO SATCOURIPATI ROY [KHULNA, June 17, 1925 ] UNTHINKABLE BUT GOD IS GREAT. MISSING FIRST TRAIN KEEP ESSENTIAL ENGAGEMENTS. LEAVING NOON. PRAY AWAIT ARRIVAL FINAL FUNERAL ARRANGEMENTS. THINK BODY SHOULD BE RECEIVED RUSSA ROAD UNLESS FRIENDS HAVE VALID REASONS CONTRARY. NATION’S WORK MUST NOT STOP BUT ADVANCE DOUBLE SPEED HIS GREAT SPIRIT NOBLE EXAMPLE GUIDING US. HOPE PARTY STRIF WILL BE HUSHE AND ALL WILL HEARTILY JOIN DO HONOUR 1 The reference is not clear. 2 This and the telegrams that follow were sent on the passing away of C. R. Das on June 16, at Darjeeling. Gandhiji received the news at Khulna on the following day. 3 Mona Das VOL.32 : 17 JUNE, 1925 - 24 SEPTEMBER, 1925 1 MEMORY THIS IDOL OF BENGAL AND ONE OF GREATEST OF INDIA’S SERVANTS. CANCELLING ASSAM TOUR. GANDHI From a photostat : S.N. 10644 4. TELEGRAM TO URMILA DEVI [KHULNA, June 17, 1925 ] URMILA DEVI NATURAL GRIEVE OVER DEATH LOVED ONES. BRAVE REMAIN UNPERTURBED. I WANT YOU BE BRAVE AND MAKE EVERY MAN YOUR BLOOD BROTHER. REACHING EVENING. GANDHI From a photostat : S.N. -

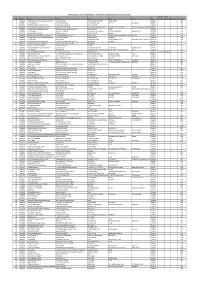

Share Liable to Be Transferres to IEPF Lying in UNCLAIMED SUSPENSE ACCOUNT

SHARES LIABLE TO BE TRANSFERRED TO IEPF LYING IN UNCLAIMED SUSPENSE ACCOUNT Second Third S.No Folio Name Add1 Add2 Add3 Add4 PIN Holder Holder Delivery Shares 1 000010 HARENDRA KUMAR MAGANLAL MEHTA C/O SHRINAGAR 1198 CHANDNI CHOWK DELHI 110006 110006 0 480 2 000013 N S SUNDARAM 9B CLEMENS ROAD POST BOX NO 480 VEPERY CHENNAI 7 600007 0 210 3 000024 BABUBHAI RANCHHODLAL SHAH 153-D KAMLA NAGAR, DELHI-110 007. 110007 0 210 4 000036 CHANDRAKANT RAOJIBHIA AMIN M/S APAJI AMIN & CO CHARTERED ACCOUNTANTS 1299/B/1 LAL DARWAJA NEAR DR K M SHAH S HOSPITAL380001 0 615 5 000042 CHAMPAKLAL ISHWARLAL SHAH 2/4456 SHIVDAS ZAVERZIS SORRI SAGRAMPARA SURAT 395002 0 7 6 000048 K V SIVANNA 181/50 4TH CROSS VYALIKAVAL EXTENSION P O MALLESWARAM BANGALORE 3 560003 0 210 7 000052 NARAYANDAS K DAGA KRISHNA MAHAL MARINE DRIVE MUMBAI 1 400001 0 210 8 000080 MANGALACHERIL SAMUEL ABRAHAM AVT RUBBER PRODUCTS LTD PLOT NO 14-C COCHIN EXPORT PROCESSING ZONE COCHIN 682030 0 502 9 000089 RAMASWAMY PILLAI RAMACHANDRAN 1 PATULLOS ROAD MOUNT ROAD CHENNAI 2 600002 0 435 10 000134 P A ANTONY JOSEALAYAM MUNDAKAPADAM P O ATHIRAMPUZHA DIST-KOTTAYAM KERALA STATE686562 0 210 11 000168 S KOTHANDA RAMAN NAYANAR 11 MADHAVA PERUMAL KOVIL ST MYLAPORE CHENNAI 600004 0 435 12 000171 JETHALAL PANJALAL PAREKH D K ARTS &SCIENCE COLLEGE JAMNAGAR 361001 0 67 13 000173 SAJINI TULSIDAS DASWANI 24 KAHUN ROAD POONA 1 411001 0 1510 14 000226 KRISHNAMOORTY VENNELAGANTI HEAD CASHIER STATE BANK OF INDIA P O GUDUR DIST NELLORE 524101 0 435 15 000227 HAR PRASAD PROPRIETOR M/S GORDHAN DASS SHEONARAINKATRA -

General Studies & Mental Ability

APOnline Limited Notations : 1.Options shown in green color and with icon are correct. 2.Options shown in red color and with icon are incorrect. Question Paper Name : GSMA 13032020 S1 Subject Name : General Studies and Mental Ability Creation Date : 2020-03-13 13:10:04 Duration : 150 Total Marks : 150 Display Marks: Yes Share Answer Key With Delivery Engine : No Actual Answer Key : Yes Calculator : None Magnifying Glass Required? : No Ruler Required? : No Eraser Required? : No Scratch Pad Required? : No Rough Sketch/Notepad Required? : No Protractor Required? : No Show Watermark on Console? : Yes Highlighter : No Auto Save on Console? : No General Studies and Mental Ability Group Number : 1 Group Id : 2310983 Is this Group for Examiner? : No General Studies and Mental Ability Section Id : 2310983 Section Number : 1 Section type : Online Display Number Panel : Yes Group All Questions : Yes Mark As Answered Required? : Yes Sub-Section Number : 1 Sub-Section Id : 2310983 Question Shuffling Allowed : Yes Question Number : 1 Question Id : 231098751 Question Type : MCQ Option Shuffling : Yes Display Question Number : Yes Is Question Mandatory : No Single Line Question Option : No Negative Marks Display Text : 1/3 Option Orientation : Vertical Correct Marks : 1 Wrong Marks : 0.33 In the honour of 200th birth anniversary of______, the World Health Organization has designated the year 2020 as the “Year of Nurse and Midwife" Options : 1. Florence Nightingale 2. Clara Barton 3. Margaret Sanger 4. Elizabeth Grace Neill Question Number : 2 Question Id : 231098752 Question Type : MCQ Option Shuffling : Yes Display Question Number : Yes Is Question Mandatory : No Single Line Question Option : No Negative Marks Display Text : 1/3 Option Orientation : Vertical Correct Marks : 1 Wrong Marks : 0.33 According to the Henley Passport Index, which country's passport is rated as number one with which its citizens can access maximum number of destinations without a prior visa? Note: For this question, discrepancy is found in question/answer. -

Two-Eyed Dialogue: Reflections After Fifty Years

TWO-EYED DIALOGUE Reflections after Fifty Years George Gispert-Sauch IFTY YEARS AGO, MY JESUIT SUPERIOR in Mumbai (Bombay) asked me Fto enrol in the University for a Master’s degree in Sanskrit. His intention was that I should prepare myself for a ministry of intercultural dialogue, to be carried out by a team of Jesuits. Dialogue was not yet a popular word, or at least not a theological word. It was in the time of Pius XII, ten years before Vatican II began, and twelve before Paul VI’s Ecclesiam suam. Early Moves Towards Dialogue The Holy Spirit, however, had for a long time been preparing a new era for a Church conditioned to defensive attitudes by the nineteenth century Syllabus of Errors, and by the anti-modernist crusade a few decades later. Even at the zenith of the colonial enterprise, the meeting of civilizations and religions had given birth to a new attitude towards other cultures among some Christian individuals and small groups.1 In India, at the end of the nineteenth century, a Bengali brahmin converted to Catholicism and proclaimed himself ‘a Hindu by birth and culture, a Catholic by rebirth and faith’. His name was Brahmabandhab Upadhyay.2 This was not altogether an original idea: it had been formulated a couple of decades earlier by his own uncle, the Rev. Kali Charan Banerjee, himself a convert to the Anglican Church. Upadhyay died prematurely as a prisoner, charged with sedition by the British Government in Kolkata (Calcutta). Two years before his death, St Mary’s Theological College in Kuresong, ancestor of what is now the Vidyajyoti Faculty in Delhi, started an ‘Indian Academy’. -

Kansas City Public Library

QO C 8 26! 92 1 Jones <p. Mahatma Gandhi- kansas city public library Kansas city, missouri Books will be issued only on presentation of library card, Please report lost cards and change of residence promptly, Card holders are responsible for all books, records, films, pictures or other library materials checked out on their cards. KANSAS CITY MO. PUBLIC LIBRARY D DDD1 DB^tSbS 3 DATE DUE MAHATMA GANDHI An Interpretation " E. STANLEY JONES AN INTERPRETATION ABINGDON-COKESBURY PRESS NEW YORK NASHVILLE --.AN INTERPRETATION MCMXLVin & PIERCE in are No of the A$* fci^ntjs this book reserved.^ part without written text magr"e reproduced in any form per- misSiofi of the publishers, except brief quotations used in connection with reviews in magazines or newspapers. SEX UP, PRINTED, AND BOUND BY THE PARTHENON PRESS, AT NASHVIULE, TENNESSEE, UNITED STATES OF AMJEJUCA i HIS book was not an easy book to write not for me. When the cable came from the publishers in America asking me to write the book, I put it aside as impossible. I never write a book by request. It must come as a result of an inner urge which I cannot put aside. I felt no such inner urge about this. I have believed in and have loved Mahatma Gandhi through the years in spite of differences. I have stood in sympathy with the Mahatma and have expressed that sympathy during the years when to do so was to open one to the charge of being the queer defending the queer, the off-center defending the eccentric. -

Jird Issue 7 Svh 08 15 11 2

A forum for academic, social, and timely issues affecting religious communities around the world. Uncapping the Springs of Localization: Christian Acculturation in South India in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries, by M. Christhu Doss Introduction Identified for its diversified culture and traditions, India witnessed a process of assimilation and synthesis of cultures during the Indian subcontinent’s medieval period. Undoubtedly, however, the advent of British colonialism during the seventeenth century profoundly altered Indian life, culture, and polity. Conquering forces undermined Ancient Indian customs and values, and “Hindu” practices1 were decried as being superstitious. Consequently, the scathing attack on Indian culture and religion generated vehement criticism from English-educated Indian intelligentsia including Ram Mohan Roy, who even claimed that “the British did not want the light of knowledge to dawn on India.”2 The expansion of Christianity in India constitutes one of the most remarkable cultural transformations in its social history. Western missionaries in general and Protestant Christians in particular, who operated within and through the colonial enterprise, criticized Hindu religion in a narrow and dogmatic manner in an attempt to prove it “inferior,” discrediting it in the minds of the Indian intelligentsia.3 Consequently, scholars view the role of Western missionaries in shaping the nature and course of Christianity in India in more abrogative and adverse terms4 as their strategies, which were complex in nature, created tensions and conflicts within indigenous cultures. Christian converts in India very often felt that they were the victims of their cultural background, since missionaries had so much power and control.5 As a result, both Hindu and Christian nationalists and liberal-minded intelligentsia attempted to develop counteractive strategies to “Indianize” Christianity. -

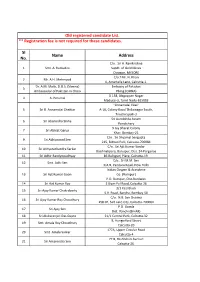

SI No. Name Address ** Registration Fee Is Not Requireě For

Old registered candidate List. ** Registration fee is not required for these candidates. SI Name Address No. C/o.. Sri A. Ramkrishna 1 Smt. A. Kumudini Supdt. of Gold Mines Osrgaon, MYSORE C/o.f Mr. N. Khan 2 Mr. A.H. Mehmood 4, Amartalla Lane, Calcutta-1. Dr. A.M. Malik, D.O.S. (Vienna) Embassy of Pakistan 3 Ambassador of Pakistan in China Piking (CHINA) D 158, Alagappan Nagar 4 A. Perumal Madurai-3, Tamil Nadu-625003 "Annamalai Vilas" 5 Sri R. Annamalai Chettiar A-16, Colony Road Thillainagar South, Tiruchirapalli-3 Sri Aurobinda Asram 6 Sri Abanindra Sinha Pondichary 9 Jay Bharat Colony 7 Sri Abhijit Garua Khar, Bombay-21 C/o.. Sri Shyamal Sengupta 9 Sri Abhiprasad Sen 215, Bidhan Palli, Calcutta-700084 C/o.. Sri Ajit Kumar Sardar 10 Sri Achyutachandra Sarkar Baishnabpara, Baruipur, Dist. 24-Parganas 11 Sri Adhir Bandyopadhyay 86 Ballygunj Place, Calcutta-19. C/o.. Sri M.M. Sen 12 Smt. Aditi Sen 3/A.B, Pandara Road, New Delhi Indian Oxygen & Acetylene 13 Sri Ajit Kumar Goon Co. (Burnpur) P.O. Burnpur, Dist-Burdwan 14 Sri Ajit Kumar Roy 2 Bipin Pal Road, Calcutta-26 3/1 Kazi Block 15 Sri Ajoy Kumar Chakraborty S.V. Road, Bandra, Bombay-50 C/o.. N.B. Sen Sharma 16 Sri Ajoy Kumar Roy Choudhury 158 CE, Salt Lake City, Calcutta-700064 P.O. Gumla 17 Sri Ajoy Sen Dist. Ranchi (BIHAR) 18 Sri Alokeranjan Das Gupta 21/1 Central Park, Calcutta-32 9, Hungerford Street 19 Smt. Amala Roy Choudhury Calcutta-20 177A, Upper Circular Road 20 Smt. -

Police Medal for Meritorious Service Republic Day-2012 Andhra Pradesh

POLICE MEDAL FOR MERITORIOUS SERVICE REPUBLIC DAY-2012 ANDHRA PRADESH 1. SHRI B MALLA REDDY, DEPUTY COMMISSIONER OF POLICE, TRAFFIC, HYDERABAD, ANDHRA PRADESH 2. SHRI P J VICTOR, SUPERINTENDENT OF POLICE, DISTRICT MEDAK , ANDHRA PRADESH 3. SHRI KOPPOLI LAKSHMI REDDY, COMMANDANT, 1ST BN APSP, HYDERABAD, ANDHRA PRADESH 4. SHRI G SUDHEER BABU, SUPERINTENDENT OF POLICE, DISTRICT- MAHABUBNAGAR, ANDHRA PRADESH 5. SHRI M VIJAYA SINGH, ADDITIONAL SUPRINTENDENT OF POLICE AND REGIONAL VIGILANCE & ENFORCEMENT OFFICER, HYDERABAD CITY-II, HYDERABAD, ANDHRA PRADESH 6. SHRI CHADARAJUPALLI VENKATESWARA RAO, DEPUTY SUPERINTENDENT OF POLICE, CID TIRUPATI, ANDHRA PRADESH 7. SHRI MALLAVARAM MALLA REDDY, DEPUTY SUPERINTENDENT OF POLICE, CID (GOW), HYDERABAD, ANDHRA PRADESH 8. SHRI E SHANKER REDDY, DEPUTY SUPERINTENDENT OF POLICE, VIGILANCE AND ENFORCEMENT DEPARTMENT, TASK FORCE, HYDERABAD, ANDHRA PRADESH 9. SHRI N V S SRINIVASA RAO, ASSAULT COMMANDER/ASSISTANT COMMANDANT, GREYHOUNDS, HYDERABAD, ANDHRA PRADESH 10. SHRI V NAGENDRA RAO, ASSAULT COMMANDER/ASSISTANT COMMANDANT, GREYHOUNDS, HYDERABAD, ANDHRA PRADESH 11. SHRI T PRABHAKAR , INSPECTOR OF POLICE, ACB, CIU, HYDERABAD, ANDHRA PRADESH 12. SHRI M NAGA BHUSHANAM, INSPECTOR OF POLICE, INTELLIGENCE, KURNOOL, ANDHRA PRADESH 13. SHRI CH P APPALANARASAIAH, RESERVE SUB INSPECTOR, ANDHRA PRADESH POLICE ACADEMY, HIMAYAT SAGAR, HYDERABAD, ANDHRA PRADESH 14. SHRI K PERRAJU, ASSISTANT SUB INSPECTOR, ACCHUTHAPURAM POLICE STATION, VISAKHAPATNAM DISTRICT , ANDHRA PRADESH 15. SHRI V RAJENDRA PRASAD, ASSISTANT SUB INSPECTOR, DISTRICT SPECIAL BRANCH OFFICE, CHILAKALAPUDI, MACHHLIPATANAM, ANDHRA PRADESH 16. SHRI S RAJAN BABU, ASSISTANT SUB INSPECTOR, PS BHUPALPALLY, WARANGAL RURAL DISTRICT, ANDHRA PRADESH 17. SHRI L SRINIVAS REDDY, ASSISTANT RESERVE SUB INSPECTOR , 10TH BN APSA BEECHPALLY, MAHABUBNAGAR, ANDHRA PRADESH 18. SHRI G MAHABOOB PEERA, ASSISTANT RESERVE SUB INSPECTOR OF POLICE, PTC AMBERPET HYDERABAD, ANDHRA PRADESH 19. -

GANDHI and JESUS the Saving Power of Nonviolence

GANDHI AND JESUS The Saving Power of Nonviolence TERRENCE J. RYNNE Founded in 1970, Orbis Books endeavors to publish works that enlighten the mind, nourish the spirit, and challenge the conscience. The publishing arm of the Maryknoll Fathers and Brothers, Orbis seeks to explore the global dimensions of the Christian faith and mission, to invite dialogue with diverse cultures and religious traditions, and to serve the cause of recon- ciliation and peace. The books published reflect the views of their authors and do not repre- sent the official position of the Maryknoll Society. To learn more about Maryknoll and Orbis Books, please visit our website at www.maryknoll.org. Copyright © 2008 by Terrence J. Rynne. Published in 2008 by Orbis Books, Maryknoll, New York 10545-0308. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. Queries regarding rights and permissions should be addressed to: Orbis Books, P.O. Box 308, Maryknoll, NY 10545-0308. Manufactured in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rynne, Terrence J., 1942– Gandhi and Jesus : the saving power of nonviolence / Terrence J. Rynne. p. cm. Based on the author’s dissertation (Ph.D.—Marquette University). Includes bibliographical references. ISBN-13: 978-1-57075-766-2 1. Nonviolence—Religious aspects. 2. Christianity and other religions—Hinduism. 3. Gandhi, Mahatma, 1869–1948. I. Title. BT736.6.R85 2008 205'.697—dc22 2007033085 CHAPTER ONE Mohandas Gandhi: A Hindu and More ohandas Gandhi was a Hindu who throughout all of his life asso- ciated with, learned from, and showed deep respect for people who Membraced the diverse religions of India, including Islam, Jainism, Christianity, Judaism, and Zoroastrianism.