Feline Exocrine Pancreatic Disease

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Title 16. Crimes and Offenses Chapter 13. Controlled Substances Article 1

TITLE 16. CRIMES AND OFFENSES CHAPTER 13. CONTROLLED SUBSTANCES ARTICLE 1. GENERAL PROVISIONS § 16-13-1. Drug related objects (a) As used in this Code section, the term: (1) "Controlled substance" shall have the same meaning as defined in Article 2 of this chapter, relating to controlled substances. For the purposes of this Code section, the term "controlled substance" shall include marijuana as defined by paragraph (16) of Code Section 16-13-21. (2) "Dangerous drug" shall have the same meaning as defined in Article 3 of this chapter, relating to dangerous drugs. (3) "Drug related object" means any machine, instrument, tool, equipment, contrivance, or device which an average person would reasonably conclude is intended to be used for one or more of the following purposes: (A) To introduce into the human body any dangerous drug or controlled substance under circumstances in violation of the laws of this state; (B) To enhance the effect on the human body of any dangerous drug or controlled substance under circumstances in violation of the laws of this state; (C) To conceal any quantity of any dangerous drug or controlled substance under circumstances in violation of the laws of this state; or (D) To test the strength, effectiveness, or purity of any dangerous drug or controlled substance under circumstances in violation of the laws of this state. (4) "Knowingly" means having general knowledge that a machine, instrument, tool, item of equipment, contrivance, or device is a drug related object or having reasonable grounds to believe that any such object is or may, to an average person, appear to be a drug related object. -

4-Aminobenzoic Acid (PABA)

SCCP/1008/06 EUROPEAN COMMISSION HEALTH & CONSUMER PROTECTION DIRECTORATE-GENERAL Directorate C - Public Health and Risk Assessment C7 - Risk assessment SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE ON CONSUMER PRODUCTS SCCP Opinion on 4-Aminobenzoic acid (PABA) COLIPA n° S1 Adopted by the SCCP during the 8th plenary meeting of 20 June 2006 SCCP/1008/06 Opinion on 4-Aminobenzoic acid (PABA) ____________________________________________________________________________________________ TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. BACKGROUND ………………………………………………… 3 2. TERMS OF REFERENCE ……………………………………………….... 3 3. OPINION ………………………………………………… 4 4. CONCLUSION ………………………………………………… 48 5. MINORITY OPINION ………………………………………………… 48 6. REFERENCES ………………………………………………… 48 7. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ………………………………………………… 56 2 SCCP/1008/06 Opinion on 4-Aminobenzoic acid (PABA) ____________________________________________________________________________________________ 1. BACKGROUND PABA or 4-Aminobenzoic acid (PABA) is listed in Annex VII part 1 no. 1 on the List of permitted UV filters that may be used in cosmetic products. The maximum authorised concentration in finished cosmetic products is 5 %. No other limitations and requirements or conditions of use and warnings are required by the SCCP. In 2001, the Commission received inquiries from Denmark expressing its concern about the use of certain UV filters in cosmetic products. In this connection an opinion on PABA was missing, as the substance has been introduced into the Annexes of the cosmetics legislation based on safety evaluations from the Member States prior to the existence of the SCCNFP. Submission I on the UV-filter 4-Aminobenzoic acid (PABA) was submitted December 2005. 2. TERMS OF REFERENCE 1. Is 4-Aminobenzoic acid (PABA) safe for continued use as a UV filter in cosmetic products under the current restriction of 5.0 % as a maximum concentration? 2. Does the SCCP consider that the use of 4-Aminobenzoic acid (PABA) is safe for the consumer in a concentration up to 5 % when used in other cosmetic products than sunscreen products? 3. -

![Ehealth DSI [Ehdsi V2.2.2-OR] Ehealth DSI – Master Value Set](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8870/ehealth-dsi-ehdsi-v2-2-2-or-ehealth-dsi-master-value-set-1028870.webp)

Ehealth DSI [Ehdsi V2.2.2-OR] Ehealth DSI – Master Value Set

MTC eHealth DSI [eHDSI v2.2.2-OR] eHealth DSI – Master Value Set Catalogue Responsible : eHDSI Solution Provider PublishDate : Wed Nov 08 16:16:10 CET 2017 © eHealth DSI eHDSI Solution Provider v2.2.2-OR Wed Nov 08 16:16:10 CET 2017 Page 1 of 490 MTC Table of Contents epSOSActiveIngredient 4 epSOSAdministrativeGender 148 epSOSAdverseEventType 149 epSOSAllergenNoDrugs 150 epSOSBloodGroup 155 epSOSBloodPressure 156 epSOSCodeNoMedication 157 epSOSCodeProb 158 epSOSConfidentiality 159 epSOSCountry 160 epSOSDisplayLabel 167 epSOSDocumentCode 170 epSOSDoseForm 171 epSOSHealthcareProfessionalRoles 184 epSOSIllnessesandDisorders 186 epSOSLanguage 448 epSOSMedicalDevices 458 epSOSNullFavor 461 epSOSPackage 462 © eHealth DSI eHDSI Solution Provider v2.2.2-OR Wed Nov 08 16:16:10 CET 2017 Page 2 of 490 MTC epSOSPersonalRelationship 464 epSOSPregnancyInformation 466 epSOSProcedures 467 epSOSReactionAllergy 470 epSOSResolutionOutcome 472 epSOSRoleClass 473 epSOSRouteofAdministration 474 epSOSSections 477 epSOSSeverity 478 epSOSSocialHistory 479 epSOSStatusCode 480 epSOSSubstitutionCode 481 epSOSTelecomAddress 482 epSOSTimingEvent 483 epSOSUnits 484 epSOSUnknownInformation 487 epSOSVaccine 488 © eHealth DSI eHDSI Solution Provider v2.2.2-OR Wed Nov 08 16:16:10 CET 2017 Page 3 of 490 MTC epSOSActiveIngredient epSOSActiveIngredient Value Set ID 1.3.6.1.4.1.12559.11.10.1.3.1.42.24 TRANSLATIONS Code System ID Code System Version Concept Code Description (FSN) 2.16.840.1.113883.6.73 2017-01 A ALIMENTARY TRACT AND METABOLISM 2.16.840.1.113883.6.73 2017-01 -

Pharmaceutical Appendix to the Tariff Schedule 2

Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States (2007) (Rev. 2) Annotated for Statistical Reporting Purposes PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE HARMONIZED TARIFF SCHEDULE Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States (2007) (Rev. 2) Annotated for Statistical Reporting Purposes PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE TARIFF SCHEDULE 2 Table 1. This table enumerates products described by International Non-proprietary Names (INN) which shall be entered free of duty under general note 13 to the tariff schedule. The Chemical Abstracts Service (CAS) registry numbers also set forth in this table are included to assist in the identification of the products concerned. For purposes of the tariff schedule, any references to a product enumerated in this table includes such product by whatever name known. ABACAVIR 136470-78-5 ACIDUM LIDADRONICUM 63132-38-7 ABAFUNGIN 129639-79-8 ACIDUM SALCAPROZICUM 183990-46-7 ABAMECTIN 65195-55-3 ACIDUM SALCLOBUZICUM 387825-03-8 ABANOQUIL 90402-40-7 ACIFRAN 72420-38-3 ABAPERIDONUM 183849-43-6 ACIPIMOX 51037-30-0 ABARELIX 183552-38-7 ACITAZANOLAST 114607-46-4 ABATACEPTUM 332348-12-6 ACITEMATE 101197-99-3 ABCIXIMAB 143653-53-6 ACITRETIN 55079-83-9 ABECARNIL 111841-85-1 ACIVICIN 42228-92-2 ABETIMUSUM 167362-48-3 ACLANTATE 39633-62-0 ABIRATERONE 154229-19-3 ACLARUBICIN 57576-44-0 ABITESARTAN 137882-98-5 ACLATONIUM NAPADISILATE 55077-30-0 ABLUKAST 96566-25-5 ACODAZOLE 79152-85-5 ABRINEURINUM 178535-93-8 ACOLBIFENUM 182167-02-8 ABUNIDAZOLE 91017-58-2 ACONIAZIDE 13410-86-1 ACADESINE 2627-69-2 ACOTIAMIDUM 185106-16-5 ACAMPROSATE 77337-76-9 -

Pharmaceuticals As Environmental Contaminants

PharmaceuticalsPharmaceuticals asas EnvironmentalEnvironmental Contaminants:Contaminants: anan OverviewOverview ofof thethe ScienceScience Christian G. Daughton, Ph.D. Chief, Environmental Chemistry Branch Environmental Sciences Division National Exposure Research Laboratory Office of Research and Development Environmental Protection Agency Las Vegas, Nevada 89119 [email protected] Office of Research and Development National Exposure Research Laboratory, Environmental Sciences Division, Las Vegas, Nevada Why and how do drugs contaminate the environment? What might it all mean? How do we prevent it? Office of Research and Development National Exposure Research Laboratory, Environmental Sciences Division, Las Vegas, Nevada This talk presents only a cursory overview of some of the many science issues surrounding the topic of pharmaceuticals as environmental contaminants Office of Research and Development National Exposure Research Laboratory, Environmental Sciences Division, Las Vegas, Nevada A Clarification We sometimes loosely (but incorrectly) refer to drugs, medicines, medications, or pharmaceuticals as being the substances that contaminant the environment. The actual environmental contaminants, however, are the active pharmaceutical ingredients – APIs. These terms are all often used interchangeably Office of Research and Development National Exposure Research Laboratory, Environmental Sciences Division, Las Vegas, Nevada Office of Research and Development Available: http://www.epa.gov/nerlesd1/chemistry/pharma/image/drawing.pdfNational -

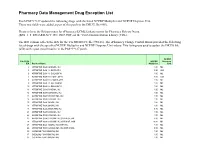

Pharmacy Data Management Drug Exception List

Pharmacy Data Management Drug Exception List Patch PSS*1*127 updated the following drugs with the listed NCPDP Multiplier and NCPDP Dispense Unit. These two fields were added as part of this patch to the DRUG file (#50). Please refer to the Release notes for ePharmacy/ECME Enhancements for Pharmacy Release Notes (BPS_1_5_EPHARMACY_RN_0907.PDF) on the VistA Documentation Library (VDL). The IEN column reflects the IEN for the VA PRODUCT file (#50.68). The ePharmacy Change Control Board provided the following list of drugs with the specified NCPDP Multiplier and NCPDP Dispense Unit values. This listing was used to update the DRUG file (#50) with a post install routine in the PSS*1*127 patch. NCPDP File 50.68 NCPDP Dispense IEN Product Name Multiplier Unit 2 ATROPINE SO4 0.4MG/ML INJ 1.00 ML 3 ATROPINE SO4 1% OINT,OPH 3.50 GM 6 ATROPINE SO4 1% SOLN,OPH 1.00 ML 7 ATROPINE SO4 0.5% OINT,OPH 3.50 GM 8 ATROPINE SO4 0.5% SOLN,OPH 1.00 ML 9 ATROPINE SO4 3% SOLN,OPH 1.00 ML 10 ATROPINE SO4 2% SOLN,OPH 1.00 ML 11 ATROPINE SO4 0.1MG/ML INJ 1.00 ML 12 ATROPINE SO4 0.05MG/ML INJ 1.00 ML 13 ATROPINE SO4 0.4MG/0.5ML INJ 1.00 ML 14 ATROPINE SO4 0.5MG/ML INJ 1.00 ML 15 ATROPINE SO4 1MG/ML INJ 1.00 ML 16 ATROPINE SO4 2MG/ML INJ 1.00 ML 18 ATROPINE SO4 2MG/0.7ML INJ 0.70 ML 21 ATROPINE SO4 0.3MG/ML INJ 1.00 ML 22 ATROPINE SO4 0.8MG/ML INJ 1.00 ML 23 ATROPINE SO4 0.1MG/ML INJ,SYRINGE,5ML 5.00 ML 24 ATROPINE SO4 0.1MG/ML INJ,SYRINGE,10ML 10.00 ML 25 ATROPINE SO4 1MG/ML INJ,AMP,1ML 1.00 ML 26 ATROPINE SO4 0.2MG/0.5ML INJ,AMP,0.5ML 0.50 ML 30 CODEINE PO4 30MG/ML -

Chronic Pancreatitis: Introduction

Chronic Pancreatitis: Introduction Authors: Anthony N. Kalloo, MD; Lynn Norwitz, BS; Charles J. Yeo, MD Chronic pancreatitis is a relatively rare disorder occurring in about 20 per 100,000 population. The disease is progressive with persistent inflammation leading to damage and/or destruction of the pancreas . Endocrine and exocrine functional impairment results from the irreversible pancreatic injury. The pancreas is located deep in the retroperitoneal space of the upper part of the abdomen (Figure 1). It is almost completely covered by the stomach and duodenum . This elongated gland (12–20 cm in the adult) has a lobe-like structure. Variation in shape and exact body location is common. In most people, the larger part of the gland's head is located to the right of the spine or directly over the spinal column and extends to the spleen . The pancreas has both exocrine and endocrine functions. In its exocrine capacity, the acinar cells produce digestive juices, which are secreted into the intestine and are essential in the breakdown and metabolism of proteins, fats and carbohydrates. In its endocrine function capacity, the pancreas also produces insulin and glucagon , which are secreted into the blood to regulate glucose levels. Figure 1. Location of the pancreas in the body. What is Chronic Pancreatitis? Chronic pancreatitis is characterized by inflammatory changes of the pancreas involving some or all of the following: fibrosis, calcification, pancreatic ductal inflammation, and pancreatic stone formation (Figure 2). Although autopsies indicate that there is a 0.5–5% incidence of pancreatitis, the true prevalence is unknown. In recent years, there have been several attempts to classify chronic pancreatitis, but these have met with difficulty for several reasons. -

PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX to the HARMONIZED TARIFF SCHEDULE Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States (2008) (Rev

Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States (2008) (Rev. 2) Annotated for Statistical Reporting Purposes PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE HARMONIZED TARIFF SCHEDULE Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States (2008) (Rev. 2) Annotated for Statistical Reporting Purposes PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE TARIFF SCHEDULE 2 Table 1. This table enumerates products described by International Non-proprietary Names (INN) which shall be entered free of duty under general note 13 to the tariff schedule. The Chemical Abstracts Service (CAS) registry numbers also set forth in this table are included to assist in the identification of the products concerned. For purposes of the tariff schedule, any references to a product enumerated in this table includes such product by whatever name known. ABACAVIR 136470-78-5 ACIDUM GADOCOLETICUM 280776-87-6 ABAFUNGIN 129639-79-8 ACIDUM LIDADRONICUM 63132-38-7 ABAMECTIN 65195-55-3 ACIDUM SALCAPROZICUM 183990-46-7 ABANOQUIL 90402-40-7 ACIDUM SALCLOBUZICUM 387825-03-8 ABAPERIDONUM 183849-43-6 ACIFRAN 72420-38-3 ABARELIX 183552-38-7 ACIPIMOX 51037-30-0 ABATACEPTUM 332348-12-6 ACITAZANOLAST 114607-46-4 ABCIXIMAB 143653-53-6 ACITEMATE 101197-99-3 ABECARNIL 111841-85-1 ACITRETIN 55079-83-9 ABETIMUSUM 167362-48-3 ACIVICIN 42228-92-2 ABIRATERONE 154229-19-3 ACLANTATE 39633-62-0 ABITESARTAN 137882-98-5 ACLARUBICIN 57576-44-0 ABLUKAST 96566-25-5 ACLATONIUM NAPADISILATE 55077-30-0 ABRINEURINUM 178535-93-8 ACODAZOLE 79152-85-5 ABUNIDAZOLE 91017-58-2 ACOLBIFENUM 182167-02-8 ACADESINE 2627-69-2 ACONIAZIDE 13410-86-1 ACAMPROSATE -

Simplified Oral Pancreatic Function Test

Arch Dis Child: first published as 10.1136/adc.63.7.780 on 1 July 1988. Downloaded from Archives of Disease in Childhood, 1988, 63, 780-784 Simplified oral pancreatic function test J W L PUNTIS,* J D BERG,t B M BUCKLEY,t I W BOOTH,* AND A S McNEISH* *Institute of Child Health, University of Birmingham, Birmingham Children's Hospital, and tDepartment of Clinical Biochemistry, Sandwell District General Hospital, West Bromwich, West Midlands SUMMARY The standard Bentiromide test and a new modified test using p-aminosalicylic acid (PAS) as a pharmacokinetic marker for p-aminobenzoic acid (PABA) have been evaluated in the detection of pancreatic exocrine insufficiency in children. The conventional two day test using a colorimetric assay for urinary PABA discriminated poorly between five children with pancreatic insufficiency and 13 others with normal pancreatic function. Two further groups of patients, comprising 28 with pancreatic exocrine insufficiency and 20 with normal pancreatic function underwent the modified test, and urine samples were analysed by high performance liquid chromatography. The results showed a complete separation between groups. The use of PAS eliminates a number of sources of error inherent in a two day Bentiromide test and provides a simplified and accurate diagnostic test for pancreatic insufficiency. The PABA-PAS modified test enables collection of the urine to be done during a single six hour period. Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency is often considered ordered gut motility or an enteropathy (which result in the differential diagnosis of failure to thrive, in low PABA absorption) or in those with hepatic or protracted diarrhoea, or steatorrhoea. -

Human Pancreatic Exocrine Response to Nutrients in Health and Disease

vi1 REVIEW Human pancreatic exocrine response to nutrients in health Gut: first published as 10.1136/gut.2005.065946 on 10 June 2005. Downloaded from and disease J Keller, P Layer ............................................................................................................................... Gut 2005;54(Suppl VI):vi1–vi28. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.065946 1.0 INTRODUCTION exocrine response to various endogenous stimuli. Optimal digestion and absorption of nutrients This chapter will summarise literature data on requires a complex interaction among motor and pancreatic exocrine response to a normal diet, its secretory functions of the gastrointestinal tract. physical and biochemical properties, and to Digestion of macronutrients is a prerequisite for administration of individual food components absorption and occurs mostly via enzymatic in healthy humans with respect to total pan- hydrolysis. In this context, pancreatic enzymes, creatic secretion, secretion of individual in particular lipase, amylase, trypsin, and chy- enzymes, ratios of enzymes, intraluminal pH motrypsin, play the most important role but and bicarbonate and bile acid secretion. several brush border enzymes as well as other pancreatic and extrapancreatic enzymes also 2.2 Pancreatic response to a normal diet participate in macronutrient digestion. The cru- In the fasting state, human pancreatic exocrine cial importance of pancreatic exocrine function is secretion is cyclical and closely correlated with reflected by the detrimental malabsorption in upper gastrointestinal -

Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States (2004) -- Supplement 1 Annotated for Statistical Reporting Purposes

Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States (2004) -- Supplement 1 Annotated for Statistical Reporting Purposes PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE HARMONIZED TARIFF SCHEDULE Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States (2004) -- Supplement 1 Annotated for Statistical Reporting Purposes PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE TARIFF SCHEDULE 2 Table 1. This table enumerates products described by International Non-proprietary Names (INN) which shall be entered free of duty under general note 13 to the tariff schedule. The Chemical Abstracts Service (CAS) registry numbers also set forth in this table are included to assist in the identification of the products concerned. For purposes of the tariff schedule, any references to a product enumerated in this table includes such product by whatever name known. Product CAS No. Product CAS No. ABACAVIR 136470-78-5 ACEXAMIC ACID 57-08-9 ABAFUNGIN 129639-79-8 ACICLOVIR 59277-89-3 ABAMECTIN 65195-55-3 ACIFRAN 72420-38-3 ABANOQUIL 90402-40-7 ACIPIMOX 51037-30-0 ABARELIX 183552-38-7 ACITAZANOLAST 114607-46-4 ABCIXIMAB 143653-53-6 ACITEMATE 101197-99-3 ABECARNIL 111841-85-1 ACITRETIN 55079-83-9 ABIRATERONE 154229-19-3 ACIVICIN 42228-92-2 ABITESARTAN 137882-98-5 ACLANTATE 39633-62-0 ABLUKAST 96566-25-5 ACLARUBICIN 57576-44-0 ABUNIDAZOLE 91017-58-2 ACLATONIUM NAPADISILATE 55077-30-0 ACADESINE 2627-69-2 ACODAZOLE 79152-85-5 ACAMPROSATE 77337-76-9 ACONIAZIDE 13410-86-1 ACAPRAZINE 55485-20-6 ACOXATRINE 748-44-7 ACARBOSE 56180-94-0 ACREOZAST 123548-56-1 ACEBROCHOL 514-50-1 ACRIDOREX 47487-22-9 ACEBURIC ACID 26976-72-7 -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2002/0010208A1 Shashoua Et Al

US 2002001 0208A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2002/0010208A1 Shashoua et al. (43) Pub. Date: Jan. 24, 2002 (54) DHA-PHARMACEUTICAL AGENT Related U.S. Application Data CONJUGATES OF TAXANES (63) Continuation of application No. 09/135,291, filed on (76) Inventors: Victor Shashoua, Brookline, MA (US); Aug. 17, 1998, now abandoned, which is a continu Charles Swindell, Merion, PA (US); ation of application No. 08/651,312, filed on May 22, Nigel Webb, Bryn Mawr, PA (US); 1996, now Pat. No. 5,795,909. Matthews Bradley, Layton, PA (US) Publication Classification Correspondence Address: Edward R. Gates, Esq. (51) Int. Cl." ............................................ A61K 31/337 Wolf, Greenfield & Sacks, P.C. (52) U.S. Cl. .............................................................. 514/449 600 Atlantic Avenue Boston, MA 02210 (US) (57) ABSTRACT The invention provides conjugates of cis-docosahexaenoic (21) Appl. No.: 09/846,838 acid and pharmaceutical agents useful in treating noncentral nervous System conditions. Methods for Selectively target 22) Filled: Mayy 1, 2001 ingg pharmaceuticalp agents9. to desired tissues are pprovided. Patent Application Publication Jan. 24, 2002 Sheet 1 of 14 US 2002/0010208A1 1 OO 5 O -5OO - 1 OO-9 -8 -7 -6 -5 -4 LOG-10 OF SAMPLE CONCENTRATION (MOLAR) CCRF-CEM-o- SR ----- RPM-8226----- K-562- - -A - - HL-60 (TB) -g- - MOLT4: ... O Fig. 1 1 OO 5 O -5OO -1 O O -8 -7 -6 -5 -4 -- 9 LOGo OF SAMPLE CONCENTRATION (MOLAR) A549/ATCC-o-NS326. NCEKVX 28. --Q-- NCI-H322M-...-a---Eidsf8::... NC-H522--O-- HOP-62---Fig. 2 a-- NC-H460.-------- Patent Application Publication Jan.