Reviewed by Evan Torner

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INEMA INTERNATIONAL Students, Faculty, Staff and the Community Are Invited • ADMISSION IS FREE • Donations Welcome 7:30 P.M

MURRAY STATE UNIVERSITY • Spring 2017 INEMA INTERNATIONAL Students, faculty, staff and the community are invited • ADMISSION IS FREE • Donations Welcome 7:30 p.m. Thursday, Friday and Saturday evenings • Curris Center Theater JAN. 26-27-28 • USA, 1992 MARCH 2-3-4 • USA, 2013 • SHAKESPEARE FESTIVAL THUNDERHEART WARM BODIES Dir. Michael Apted With Val Kilmer, Sam Shephard, Graham Greene. Dir. Jonathan Levine, In English and Sioux with English subtitles. Rated R, 119 mins. With Nicholas Hoult, Dave Franco, Teresa Palmer, Analeigh Tipton, John Malkovich Thunderheart is a thriller loosely based on the South Dakota Sioux Indian In English, Rated PG-13, 98 mins. uprising at Wounded Knee in 1973. An FBI man has to come to terms with his mixed blood heritage when sent to investigate a murder involving FBI A romantic horror-comedy film based on Isaac Marion's novel of the same agents and the American Indian Movement. Thunderheart dispenses with name. It is a retelling of the Romeo and Juliet love story set in an apocalyptic clichés of Indian culture while respectfully showing the traditions kept alive era. The film focuses on the development of the relationship between Julie, a on the reservation and exposing conditions on the reservation, all within the still-living woman, and "R", a zombie…A funny new twist on a classic love story, conventions of an entertaining and involving Hollywood murder mystery with WARM BODIES is a poignant tale about the power of human connection. R a message. (Axmaker, Sean. Turner Classic Movies 1992). The story is a timely exploration of civil rights issues and Julie must find a way to bridge the differences of each side to fight for a that serves as a forceful indictment of on-going injustice. -

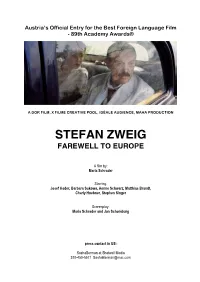

Stefan Zweig Farewell to Europe

Austria’s Official Entry for the Best Foreign Language Film - 89th Academy Awards® A DOR FILM, X FILME CREATIVE POOL, IDÉALE AUDIENCE, MAHA PRODUCTION STEFAN ZWEIG FAREWELL TO EUROPE A film by: Maria Schrader Starring: Josef Hader, Barbara Sukowa, Aenne Schwarz, Matthias Brandt, Charly Huebner, Stephen SInger Screenplay: Maria Schrader and Jan Schomburg press contact in US: SashaBerman at Shotwell Media 310-450-5571 [email protected] Table of Contents Short synopsis & press note …………………………………………………………………… 3 Cast ……............................................................................................................................ 4 Crew ……………………………………………………………………………………………… 6 Long Synopsis …………………………………………………………………………………… 7 Persons Index…………………………………………………………………………………….. 14 Interview with Maria Schrader ……………………………………………………………….... 17 Backround ………………………………………………………………………………………. 19 In front of the camera Josef Hader (Stefan Zweig)……………………………………...……………………………… 21 Barbara Sukowa (Friderike Zweig) ……………………………………………………………. 22 Aenne Schwarz (Lotte Zweig) …………………………….…………………………………… 23 Behind the camera Maria Schrader………………………………………….…………………………………………… 24 Jan Schomburg…………………………….………...……………………………………………….. 25 Danny Krausz ……………………………………………………………………………………… 26 Stefan Arndt …………..…………………………………………………………………….……… 27 Contacts……………..……………………………..………………………………………………… 28 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Technical details Austria/Germany/France, 2016 Running time 106 Minutes Aspect ratio 2,39:1 Audio format 5.1 ! 2! “Each one of us, even the smallest and the most insignificant, -

BERLIN ALEXANDERPLATZ: REMASTERED Berlinale Special BERLIN ALEXANDERPLATZ: REMASTERED BERLIN ALEXANDERPLATZ: REMASTERED Regie: Rainer Werner Fassbinder

Berlinale 2007 BERLIN ALEXANDERPLATZ: REMASTERED Berlinale Special BERLIN ALEXANDERPLATZ: REMASTERED BERLIN ALEXANDERPLATZ: REMASTERED Regie: Rainer Werner Fassbinder Deutschland 1979/1980 Darsteller Franz Biberkopf Günter Lamprecht Länge Film in 13 Teilen Reinhold Gottfried John und mit einem Mieze Barbara Sukowa Epilog: 939 Min. Eva Hanna Schygulla Format 35 mm, 1:1.37 Meck Franz Buchrieser Farbe Cilly Annemarie Düringer Stabliste Pums Ivan Desny Buch Rainer Werner Lüders Hark Bohm Fassbinder, nach Herbert Roger Fritz dem gleichnamigen Frau Bast Brigitte Mira Roman von Alfred Minna Karin Baal Döblin Lina Elisabeth Trissenaar Kamera Xaver Ida Barbara Valentin Schwarzenberger Trude Irm Hermann Kameraassistenz Josef Vavra Terah Margit Carstensen Schnitt Juliane Lorenz Sarug Helmut Griem Franz Walsch Fränze Helen Vita (= R.W. Fassbinder) Baumann Gerhard Zwerenz Ton Carsten Ullrich Barbara Sukowa, Günter Lamprecht Konrad Raul Gimenez Mischung Milan Bor Paula Mechthild Musik Peer Raben Großmann Ausstattung Helmut Grassner BERLIN ALEXANDERPLATZ: REMASTERED Witwe Angela Schmidt Werner Achmann „Vor zwanzig Jahren etwa, ich war gerade vierzehn, vielleicht auch schon Wirt Claus Holm Spezialeffekte Theo Nischwitz fünfzehn, befallen von einer fast mörderischen Pubertät, begegnete ich auf Willy Fritz Schediwy Kostüm Barbara Baum meiner ganz und gar unakademischen, extrem persönlichen, nur meiner Dreske Axel Bauer Maske Peter Knöpfle ureigenen Assoziation verpflichteten Reise durch die Weltliteratur Alfred Bruno Volker Spengler Anni Nöbauer Regieassistenz -

To Download SEARCHING for INGMAR BERGMAN

SYNOPSIS Internationally renowned director Margarethe von Trotta examines Ingmar Bergman’s life and work with a circle of his closest collaborators as well as a new generation of filmmakers. This documentary presents key components of his legacy, as it retraces themes that recurred in his life and art and takes us to the places that were central to Bergman’s creative achievements. DIRECTOR’S BIOGRAPHY The daughter of Elisabeth von Trotta and the painter Alfred Roloff, Margarethe von Trotta was born in Berlin in 1942 and spent her childhood in Düsseldorf. After fine art studies, she moved to Munich to study Germanic and Latin language. She then joined a school for dramatic arts and began an acting career, in the theatres of Düsseldorf and afterwards in the Kleines Theater of Frankfurt in 1969 and 1970. At the end of the 1960 she moved in Paris for her studies and immersed herself in the film-lover circles of the time. She took part in script redacting and directing of short films and discovered via the Nouvelle Vague directors and critics the films of Ingmar Bergman and Alfred Hitchcock. In Germany, Margarethe von Trotta has worked with a new generation of young filmmakers: Herbert Achternbusch, Volker Schlöndorff who she married in 1971 and with whom she directed and wrote The Sudden Wealth of the Poor People of Kombach (1971) and The Lost Honour of Katharina Blum (1975), as well as Rainer Werner Fassbinder who made her act in four of his films. She directed in 1978 her first long feature, The Second Awakening of Christa Klages. -

The Desire for History in Lars Von Trier's Europa and Theo

The Desire for History in Lars von Trier’s Europa and Theo An- gelopoulos’ The Suspended Step of the Stork By Angelos Koutsourakis Spring 2010 Issue of KINEMA THE PERSISTENCE OF DIALECTICS OR THE DESIRE FOR HISTORY IN LARS VON TRIER’S EUROPA AND THEO ANGELOPOULOS’ THE SUSPENDED STEP OF THE STORK In this article I intend to discuss cinema’s potential to represent history in a period that political conflict and historical referents seem to be absent. I am going to pursue this argument through a comparative reading of two films, Lars von Trier’s Europa (1991) and Theo Angelopoulos’ The Suspended Step of the Stork (1991). My contention is that these two films exploit historical narratives of the past and the present with theview to negating teleological and ahistorical assumptions that history has come to a standstill. The central topos of the postmodern theory is that the distinctions between real and fictional reference are not clear-cut and in order to gain an historical understanding one has to go beyond reductionist simplifications between facts and representations. This loss of historical specificity has been heightened by the collapse of a socialist alternative which provided for many years a sense of political conflict. European Cinema has responded in that loss of historicity in various ways. For the most part history becomes a fetish that puts forward a postmodern nostalgia that does not offer an understanding of the historical present. For instance, in Wolfgang Becker’s Goodbye Lenin (2003) the East German past becomes a site of fascination stemming from the absence of overt concrete political conflict in contemporary history. -

Filmprogramm Zur Ausstellung Mo., 1. Juni, 19.30 Uhr Warnung Vor Einer

Filmprogramm zur Ausstellung Mo., 1. Juni, 19.30 Uhr Warnung vor einer heiligen Nutte Rainer Werner Fassbinder BRD 1970 Mit Lou Castel, Eddie Constantine, Hanna Schygulla, Marquard Bohm DCP OmE 103 Minuten Mo., 8. Juni, 19.30 Uhr Händler der vier Jahreszeiten Rainer Werner Fassbinder BRD 1971 Mit Hans Hirschmüller, Irm Hermann DCP OmE 89 Minuten Mo., 15. Juni, 19.30 Uhr Die bitteren Tränen der Petra von Kant Rainer Werner Fassbinder BRD 1972 Mit Margit Carstensen, Hanna Schygulla, Irm Hermann DCP OmE 124 Minuten Mo., 22. Juni, 19 Uhr Welt am Draht Rainer Werner Fassbinder BRD 1973 Mit Klaus Löwitsch, Mascha Rabben, Karl-Heinz Vosgerau, Ivan Desny, Barbara Valentin DCP OmE 210 Minuten Mo., 29. Juni, 19.30 Uhr Angst essen Seele auf Rainer Werner Fassbinder BRD 1974 Mit Brigitte Mira, El Hedi Ben Salem, Barbara Valentin, Irm Hermann DCP OmE 93 Minuten Mo., 6. Juli, 19.30 Uhr Martha Rainer Werner Fassbinder BRD 1974 Mit Margit Carstensen, Karlheinz Böhm 35mm 116 Minuten Mo., 13. Juli, 19.30 Uhr Fontane Effi Briest Rainer Werner Fassbinder BRD 1974 Mit Hanna Schygulla, Wolfgang Schenck, Karlheinz Böhm DCP OmE 141 Minuten Mo., 20. Juli, 19.30 Uhr Faustrecht der Freiheit Rainer Werner Fassbinder BRD 1975 Mit Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Peter Chatel, Karlheinz Böhm DCP OmE 123 Minuten Mo., 27. Juli, 19.30 Uhr Chinesisches Roulette Rainer Werner Fassbinder BRD 1976 Mit Margit Carstensen, Anna Karina DCP OmE 86 Minuten Mo., 3. August, 19.30 Uhr Die Ehe der Maria Braun Rainer Werner Fassbinder BRD 1978 Mit Hanna Schygulla, Klaus Löwitsch, Ivan Desny, Gottfried John DCP OmE 120 Minuten Mo., 10. -

German Videos - (Last Update December 5, 2019) Use the Find Function to Search This List

German Videos - (last update December 5, 2019) Use the Find function to search this list Aguirre, The Wrath of God Director: Werner Herzog with Klaus Kinski. 1972, 94 minutes, German with English subtitles. A band of Spanish conquistadors travels into the Amazon jungle searching for the legendary city of El Dorado, but their leader’s obsessions soon turn to madness.LLC Library CALL NO. GR 009 Aimée and Jaguar DVD CALL NO. GR 132 Ali: Fear Eats the Soul Director: Rainer Werner Fassbinder. with Brigitte Mira, El Edi Ben Salem. 1974, 94 minutes, German with English subtitles. A widowed German cleaning lady in her 60s, over the objections of her friends and family, marries an Arab mechanic half her age in this engrossing drama. LLC Library CALL NO. GR 077 All Quiet on the Western Front DVD CALL NO. GR 134 A/B Alles Gute (chapters 1 – 4) CALL NO. GR 034-1 Alles Gute (chapters 13 – 16) CALL NO. GR 034-4 Alles Gute (chapters 17 – 20) CALL NO. GR 034-5 Alles Gute (chapters 21 – 24) CALL NO. GR 034-6 Alles Gute (chapters 25 – 26) CALL NO. GR 034-7 Alles Gute (chapters 9 – 12) CALL NO. GR 034-3 Alpen – see Berlin see Berlin Deutsche Welle – Schauplatz Deutschland, 10-08-91. [ Opening missing ], German with English subtitles. LLC Library Alpine Austria – The Power of Tradition LLC Library CALL NO. GR 044 Amerikaner, Ein – see Was heißt heir Deutsch? LLC Library Annette von Droste-Hülshoff CALL NO. GR 120 Art of the Middle Ages 1992 Studio Quart, about 30 minutes. -

The Feminine Sublime in 21St Century Surrealist Cinema

Wright State University CORE Scholar Browse all Theses and Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2016 The Feminine Sublime in 21st Century Surrealist Cinema Abigail Sorensen Wright State University Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Repository Citation Sorensen, Abigail, "The Feminine Sublime in 21st Century Surrealist Cinema" (2016). Browse all Theses and Dissertations. 1501. https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all/1501 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Browse all Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE FEMININE SUBLIME IN 21ST CENTURY SURREALIST CINEMA A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Humanities By ABIGAIL SORENSEN B.A., Wright State University, 2013 2016 Wright State University 2 ABSTRACT Sorensen, Abigail. M. Hum. Humanities Department, Wright State University, 2016. The Feminine Sublime in 21st Century Surrealist Cinema. This thesis will examine how the characters in three contemporary surrealist films, Mulholland Dr. (2001), Under the Skin (2013), and Melancholia (2011), experience the sublime. In each film, the female characters are marked by the “otherness” of femininity along with the consequential philosophical and social alienation due to their marginalized roles within the patriarchal structure. Their confrontations with the otherness of sublimity are disparate from their male counterparts, whose experiences are not complicated by patriarchal oppression. The sublimity the characters are faced with forces them to recognize their subjugated social positioning. -

Feature Films LIBRARY Latest Releases

feature films LIBRARY latest releases TWO OF US BLIND SPOT by Filippo Meneghetti by Pierre Trividic & Patrick-Mario Bernard With: Barbara Sukowa, Martine Chevallier, Léa Drucker With: Jean-Christophe Folly, Isabelle Carré, Golshifteh Farahani Nina and Madeleine, two retired women, are secretly deeply in love for decades. From everybody's point of view, including Dominick always had the power to turn invisible but he chose Madeleine's family, they are simply neighbors living on the to keep it secret and barely used it. One day, his ability to top floor of their building. They come and go between their control it gets out of his hands, throwing his life and loves into two apartments, sharing the tender delights of everyday turmoil… life together. Until the day their relationship is turned upside down by an unexpected event leading Madelein's daughter to slowly unveil the truth about them. Paprika Films - Artémis Productions - Tarantula Ex Nihilo - Les Films De Pierre France - Benelux / 2019 France / 2019 ANGOULÊME - PALM SPRINGS - HONORABLE MENTION WHATEVER HAPPENED JURY PRIZE SAF TORONTO TO MY REVOLUTION by Ali Vatansever by Judith Davis With: Saadet Işil Akşoy, Erol Afşin, Onur Buldu, Ümmü Putgül With: Judith Davis, Malik Zidi, Claire Dumas Istanbul, 2018. Urban transformation is sweeping away local Angèle, a young and restless activist, never stops crusading communities. Kamil and his wife Remziye are threatened to for social justice, losing sight of her friends, family and love lose their house. When Kamil suddenly disappears, Remziye in the process. have to face the consequences of his actions. Agat Films - Apsara Films Terminal Film - 2Pilots Film - 4 Proof Film France / 88' / 2018 Turkey - Germany - Romania / 102' / 2018 TALLINN BLACK NIGHTS TRANSFRONTEIRA PERIFERIAS - SLAM RAIVA AUDIENCE AWARD by Partho Sen-Gupta by Sérgio Tréfaut SIX SOPHIA AWARDS INCLUDING BEST FILM With: Adam Bakri, Rachael Blake, Abbey Azziz With: Isabel Ruth, Leonor Siveira, Hugo Bentes Ricky is a young Arab Australian whose peaceful suburban Portugal, 1950. -

Fassbinder Rétrospective 11 Avril – 16 Mai

RAINER WERNER FASSBINDER RÉTROSPECTIVE 11 AVRIL – 16 MAI Lola, une femme allemande 66 LE MONDE COMME VOLONTÉ ET REPRÉSENTATION Venu du théâtre, auteur d’une imposante œuvre cinématographique et télé- visuelle interrompue par sa mort prématurée, Fassbinder a été l’une des plus puissantes figures du nouveau cinéma allemand. Ses films dénoncent un certain état de la société allemande, sa violence de classes et le refoulé de son passé nazi. « Pas d’utopie est une utopie. » Rainer Werner Fassbinder, 1971 Rainer Werner Fassbinder comparait sa filmographie à une maison. Les mauvaises langues sont tentées d’orner l’entrée de l’édifice d’un dantesque « Désespoir », en anglais Despair – comme son adaptation du roman éponyme de Vladimir Nabokov (1978). C’est oublier, au-delà de la chape de plomb existentielle associée à son ciné- RAINER WERNER FASSBINDER WERNER RAINER ma (Années 70 ! Papier peint brunâtre !), que le sous-titre de Despair était Voyage vers la lumière. Tendue entre ciel et terre, la beauté mélancolique de l’œuvre de Fassbinder est celle d’un cinéma de l’utopie, sous le sceau du rimbaldien « Je est un autre » qu’un personnage lâche dans sa pièce L’Ordure, la Ville et la Mort. L’archétype du personnage fassbinderien se projette, rêve d’une âme frère/sœur avec qui il ne ferait qu’un, son double, son reflet mais aussi (et surtout) son bour- reau. « Chaque homme tue ce qu’il aime », chantait Jeanne Moreau dans Querelle. Le coup de foudre entre le personnage-titre de Martha et son futur époux, traité comme un ballet de poupées mécaniques, témoigne de la ferveur fantasmatique dans laquelle le protagoniste fassbindérien se noie par amour et pour cette utopie. -

The German Film Series Spring 2018

Amherst College Department of German Presents The German Film Series Spring 2018 Thursdays at 4:00 and 7:30 pm, Stirn Auditorium, Amherst College (in German with English subtitles) February 8th: Hannah Arendt (Margarethe von Trotta, 2012; 113 min.) Fascinating biopic with acclaimed actress Barbara Sukowa in the title role, centering on the controversies that erupted in 1961 when the famous German-Jewish political philosopher reported on the trial of Adolf Eichmann in Israel. February 22nd: Berlin Calling (Hannes Stöhr, 2008; 105 min.) Fast paced film depicting Ickarus, a DJ/Producer, who is working on an album and touring techno clubs with his girlfriend. After consuming drugs, he goes into a drug induced psychosis and ends up in a psychiatric hospital. A prize winning tragic comedy in the Berlin of today. March 8th: Grüße aus Fukushima (Greetings from Fukushima, Doris Dörrie, 2016, 105 min.) Award-winning poetic drama about the aftermath of the 2011 nuclear disaster: traveling to Fukushima, a troubled young German woman encounters a feisty elderly Japanese lady who, after years of living in a makeshift container city, is determined to rebuild her life at home, right in the contaminated evacuation zone. Screenings co-sponsored by the Goethe-Institut Boston. March 22nd: Stefan Zweig: Farewell to Europe (Maria Schrader, 2016; 106 mins.) Emotional drama telling the story of the Austrian writer and his life in exile from 1936 to 1942. Zweig was one of the most famous writers of his time, but as a Jewish intellectual he struggled to find the right stance towards the events in Nazi Germany. -

Hannah Arendt FRAUEN Samstag, 5.3

PROGRAMMÜBERBLICK Samstag, 5.3. 17 Uhr Hannah Arendt FRAUEN Samstag, 5.3. 20 Uhr Suff ragett e FILM Sonntag, 6.3. 10 Uhr KINOBRUNCH FESTIVAL Sonntag, 6.3. 11 Uhr Rosie Sonntag, 6.3. 17 Uhr Und in der Mitt e der Erde war Feuer 5. + 6. März 2016 Sonntag, 6.3. 19 Uhr Die abhandene Welt EINTRITT Pro Film EUR 8,00 „Rosie“ Eintritt frei, freiwillige Spende erbeten Vorverkaufskarten sind an der MAXOOM-Kasse, Tel. 03332/62250-151, erhältlich. Reservierte Karten müssen bis spätestens 15 Minuten vor Filmbeginn abgeholt werden. Infos unter Tel. 03332/62250-151 und auf www.maxoom.at VeranstalterInnen: Mag.a Liesbeth Horvath a Mag. Susanne Prechtl Zum Internationalen Frauentag Auch Männer sind herzlich willkommen! das Gartenatelier Impressum: oekopark Errichtungs GmbH Am Ökopark 10 • 8230 Hartberg • [email protected] T 03332/622 50-151 • www.oekopark.at • www.maxoom.at MAXOOM MAXOOM powered by OEKOPARK ERLEBNISREICH Deutschland 2012, 113 Min., ab 6 J., Biografi e, Re- Erfahrungen in mehreren Arti keln. Dadurch ent- gie: Margarethe von Trott a, mit Barbara Sukowa, steht ihr berühmtestes und zugleich umstritt enes HANNAH Axel Milberg, Janet Mc Teer, Ulrich Noethen Werk „Eichmann in Jerusalem – Ein Bericht von Hannah Arendt arbeitet als Reporterin für „The der Banalität des Bösen“, das bei vielen aufgrund ARENDT New Yorker“. 1961 nimmt sie im Auft rag der Zei- ihrer Darstellung des Angeklagten auf ein zwie- tung am Eichmann-Prozess in Jerusalem teil. Die spälti ges Echo stößt. Arendt sieht in Eichmann anerkannte Philosophin und Schrift stellerin will nicht das große Monster, für das ihn die Men- anhand des Prozesses den Charakter des verant- schen halten.