Hormonal Modulation of Mineral Metabolism in Reproduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Associations Between Serum Leptin Level and Bone Turnover in Kidney Transplant Recipients

Associations between Serum Leptin Level and Bone Turnover in Kidney Transplant Recipients ʈ ʈ ʈ Csaba P. Kovesdy,*† Miklos Z. Molnar,‡§ Maria E. Czira, Anna Rudas, Akos Ujszaszi, Laszlo Rosivall,‡ Miklos Szathmari,¶ Adrian Covic,** Andras Keszei,†† Gabriella Beko,‡‡ ʈ Peter Lakatos,¶ Janos Kosa,¶ and Istvan Mucsi §§ *Division of Nephrology, Salem Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Salem, Virginia; †Division of Nephrology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia; ‡Institute of Pathophysiology, Semmelweis University, Budapest, Hungary; §Harold Simmons Center for Chronic Disease Research & Epidemiology, Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute at ʈ Harbor-University of California–Los Angeles Medical Center, Torrance, California; Institute of Behavioral Sciences, Semmelweis University, Budapest, Hungary; ¶First Department of Internal Medicine, Semmelweis University, Budapest, Hungary; **University of Medicine Gr T Popa, Iasi, Romania; ††Department of Epidemiology, Maastricht University, Maastricht, Netherlands; ‡‡Central Laboratory, Semmelweis University, Budapest, Hungary; and §§Division of Nephrology, Department of Medicine, McGill University Health Center, Montreal, Quebec, Canada Background and objectives: Obesity is associated with increased parathyroid hormone (PTH) in the general population and in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). A direct effect of adipose tissue on bone turnover through leptin production has been suggested, but such an association has not been explored in kidney transplant recipients. Design, setting, participants, & measurements: This study examined associations of serum leptin with PTH and with biomarkers of bone turnover (serum beta crosslaps [CTX, a marker of bone resorption] and osteocalcin [OC, a marker of bone formation]) in 978 kidney transplant recipients. Associations were examined in multivariable regression models. Path analyses were used to determine if the association of leptin with bone turnover is independent of PTH. -

Endocrine System WS19

Endocrine System Human Physiology Unit 3 Endocrine System • Various glands located throughout the body • Some organs may also have endocrine functions • Endocrine glands/organs synthesize and release hormones • Hormones travel in plasma to target cells Functions of the Endocrine System • Differentiation of nervous and reproductive system during fetal development • Regulation of growth and development • Regulation of the reproductive system • Maintains homeostasis • Responds to changes from resting state Mechanisms of Hormone Regulation • Hormones have different rates and rhythms of secretion • Hormones are regulated by feedback systems to maintain homeostasis • Receptors for hormones are only on specific effector cells • Excretion of hormones vary for steroid hormones and peptide hormones Regulation of Hormone Secretion • Release of hormones occurs in response to • A change from resting conditions • Maintaining a regulated level of hormones or substances • Hormone release is regulated by • Chemical factors (glucose, calcium) • Endocrine factors (tropic hormones, HPA) HPA = Hypothalamic-Pituitary Axis • Neural controls (sympathetic activation) Hormone Feedback Systems Negative feedback maintains hormone concentrations within physiological ranges • Negative feedback • Feedback to one level Loss of • Long-loop Negative Feedback feedback • Feedback to two levels control often leads to • Hypothalamus-Pituitary-Gland Axis pathology Negative Feedback Short-Loop Negative Feedback Long-Loop Negative Feedback Hormone Transport Peptide/Protein Hormones -

The ENDOCRINE SYSTEM Luteinizinghormones Hormone/Follicle-Stimulating Are Chemical Hormone Messengers

the ENDOCRINE SYSTEM LuteinizingHormones hormone/follicle-stimulating are chemical hormone messengers. (LH/FSH) They bind to specific target cells Crucial for sex cell production Growth hormone–releasingwith receptors, hormone regulate (GHRH) metabolism and the sleep cycle, and contribute Thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH) Regulatesto thyroid-stimulating growth and hormone development. release The endocrine glands and organs secrete Corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) Regulatesthese to release hormones of adrenocorticotropin all over that is vitalthe to body. the production of cortisol (stress response hormone). The hypothalamus is a collection of specialized cells that serve as the central relay system between the nervous and endocrine systems. hypothalamus Growth hormone-releasing hormone (GHRH) Thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH) Regulates the release of thyroid-stimulating hormones Luteinizing hormone/follicle-stimulating hormone (LH/FSH) Crucial for sex cell production Corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) Regulates the release of adrenocorticotropin that’s vital to the production of cortisol 2 The hypothalamus translates the signals from the brain into hormones. From there, the hormones then travel to the pituitary gland. Located at the base of the brain inferior to the hypothalamus, the pituitary gland secretes endorphins, controls several other endocrine glands, and regulates the ovulation and menstrual cycles. pituitary gland 3 The anterior lobe regulates the activity of the thyroid, adrenals, and reproductive glands by producing hormones that regulate bone and tissue growth in addition to playing a role in the absorption of nutrients and minerals. anterior lobe Prolactin Vital to activating milk production in new mothers Thyrotropin Stimulates the thyroid to produce thyroid hormones vital to metabolic regulation Corticotropin Vital in stimulating the adrenal gland and the “fight-or-flight” response 4 The posterior lobe stores hormones produced by the hypothalamus. -

Endocrine Paraneoplastic Syndromes: a Review

Endocrinology & Metabolism International Journal Review Article Open Access Endocrine paraneoplastic syndromes: a review Abstract Volume 1 Issue 1 - 2015 Paraneoplastic endocrine syndromes result from ectopic production of hormones by Hala Ahmadieh,1 Asma Arabi2 different tumors. Hypercalcemia of malignancy is the most common, mostly caused by 1Division of Endocrinology, American University of Beirut, ectopic parathyroid hormone related peptide (PTHrP) production which increases bone Lebanon resorption. Other causes include the rare ectopic parathyroid hormone (PTH) production, 2Department of Internal Medicine, American University of ectopic production of 1, 25-(OH)2 vitamin D by the tumor and its adjacent macrophages and Beirut-Medical Center, Lebanon bone metastasis which by itself in addition to the local production of PTHrP at the level of the bone lead to bone resorption and thus hypercalcemia. Treatment includes extracellular Correspondence: Asma Arabi, Department of Internal fluid volume repletion, bisphosphonates or denosumab and calcitonin. Ectopic Cushing’s Medicine, Division of Endocrinology, American University of syndrome caused by ectopic ACTH production results in hypokalemia, proximal muscle Beirut-Medical Center, Po Box 11-0236, Riad El-Solh, Beirut, weakness, easy bruisability, hypertension, diabetes and psychiatric abnormalities including Lebanon, Email depression and mood disorders. Different diagnostic measures help to differentiate Cushing’s disease from ectopic Cushing’s syndrome. Treatment includes surgical resection Received: October 26, 2014 | Published: January 02, 2015 of tumor and medical therapy to suppress excess cortisol production. Ectopic secretion of ADH has been associated with different tumor types. The best treatment options include removal of the underlying tumor, chemotherapy, or radiotherapy in addition to free water restriction, demeclocycline and vaptans. -

Physiological Adaptations in Pregnancy-Resources Table

Responsibility/ Adaptations in Pregnancy Additional Information Hormones ➢ Maintaining homeostasis Perinatal Nursing – 2021 ➢ Regulation of growth Simpson, Creehan, O’Brien-Abel, Roth ➢ Development and Cellular communication & Rohan Chapter three – Physiological Changes of Pregnancy Blackburn, Susan Tucker Page 48 Placenta ➢ Responsible for transfer of nutrients to the fetus ❖ Placental Hormones are critical and waste products away from the fetus for many of the metabolic and ➢ Functions as the fetal lungs, gi, liver, kidney and endocrine changes during endocrine organ pregnancy ➢ Major Hormones ❖ Fetal bone growth and placental ❖ hCG - Human chorionic gonadotropin calcium transport is mediated ❖ hPL – Human Placental Lactogen by Parathyroid hormone related ❖ Estrogen protein or PTHrP ❖ Progesterone ❖ Corticotrophin-releasing ❖ Serves as an endocrine gland hormone or CRH and PGs have a ❖ Major Hormones major role in initiation of ❖ hCG - Human chorionic gonadotropin myometrial contractility and ❖ hPL – Human Placental Lactogen labor onset ❖ Estrogen Page 49 ❖ Progesterone ➢ HCG ➢ Primarily secreted by the placenta Page 49 1 | P a g e ➢ Major function is to maintain progesterone and estrogen production by the corpus luteum until the placental function is adequate (approximately 10 weeks post-conception) ➢ Thought to have a role in fetal testosterone and corticosteroid production and angiogenesis ➢ Found in maternal serum by within 7-8 days after implantation ➢ Positive pregnancy test – 3 weeks after conception and 5 weeks after LMP ➢ Elevated -

The Regulation of Parathyroid Hormone Secretion and Synthesis

BRIEF REVIEW www.jasn.org The Regulation of Parathyroid Hormone Secretion and Synthesis Rajiv Kumar* and James R. Thompson† *Division of Nephrology and Hypertension, Department of Internal Medicine, Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, and †Department of Physiology, Biophysics and Bioengineering, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota ABSTRACT Secondary hyperparathyroidism classically appears during the course of chronic renal basis of these observations regarding failure and sometimes after renal transplantation. Understanding the mechanisms by pathogenesis, therapy for 2°HPT in the which parathyroid hormone (PTH) synthesis and secretion are normally regulated is context of CKD and ESRD includes the important in devising methods to regulate overactivity and hyperplasia of the para- control of serum phosphate concentra- ϩ thyroid gland after the onset of renal insufficiency. Rapid regulation of PTH secretion tions, the administration of Ca2 and in response to variations in serum calcium is mediated by G-protein coupled, calcium- vitamin D analogs, and the administra- sensing receptors on parathyroid cells, whereas alterations in the stability of mRNA- tion of calcimimetics.33,34,16,35,36 encoding PTH by mRNA-binding proteins occur in response to prolonged changes in Nevertheless, 2°HPT remains a signifi- serum calcium. Independent of changes in intestinal calcium absorption and serum cant clinical problem and additional meth- calcium, 1␣,25-dihydroxyvitamin D also represses the transcription of PTH by associ- ods for the treatment of this condition would ating with the vitamin D receptor, which heterodimerizes with retinoic acid X receptors be helpful, especially in refractory situations, to bind vitamin D-response elements within the PTH gene. -

21 CFR Ch. I (4–1–20 Edition) § 862.1542

§ 862.1542 21 CFR Ch. I (4–1–20 Edition) subpart E of part 807 of this chapter acid) in serum, plasma, and urine. subject to § 862.9. Measurements of phenylalanine are used in the diagnosis and treatment of [52 FR 16122, May 1, 1987, as amended at 65 FR 2307, Jan. 14, 2000] congenital phenylketonuria which, if untreated, may cause mental retarda- § 862.1542 Oxalate test system. tion. (a) Identification. An oxalate test sys- (b) Classification. Class II. tem is a device intended to measure § 862.1560 Urinary phenylketones the concentration of oxalate in urine. (nonquantitative) test system. Measurements of oxalate are used to aid in the diagnosis or treatment of (a) Identification. A urinary urinary stones or certain other meta- phenylketones (nonquantitative) test bolic disorders. system is a device intended to identify (b) Classification. Class I (general con- phenylketones (such as phenylpyruvic trols). The device is exempt from the acid) in urine. The identification of premarket notification procedures in urinary phenylketones is used in the subpart E of part 807 of this chapter diagnosis and treatment of congenital subject to § 862.9. phenylketonuria which, if untreated, may cause mental retardation. [52 FR 16122, May 1, 1987, as amended at 65 (b) Classification. Class I (general con- FR 2307, Jan. 14, 2000] trols). The device is exempt from the § 862.1545 Parathyroid hormone test premarket notification procedures in system. subpart E of part 807 of this chapter subject to § 862.9. (a) Identification. A parathyroid hor- mone test system is a device intended [52 FR 16122, May 1, 1987, as amended at 65 to measure the levels of parathyroid FR 2307, Jan. -

The Unique Endocrine Milieu of the Fetus

Perspectives The Unique Endocrine Milieu of The Fetus Delbert A. Fisher Department ofPediatrics, University of California, Los Angeles School ofMedicine, Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, Torrance, California 90509 Since the pioneering studies of Jost and colleagues four decades hormone precursor. DHAS is transported to the liver for 16- ago, there has been impressive progress in our understanding of hydroxylation and/or to the placenta, where it is hydrolyzed by the intrauterine endocrine milieu (1). Fetal endocrine physiology a steroid sulfatase and utilized as substrate for placental estrogen differs in many important ways from the endocrinology of post- biosynthesis. DHAS serves as substrate for placental estrone and natal life. It is characterized by a series of unique fetal endocrine estradiol production; 160H-DHAS is the major substrate for organs, by a number of hormones or metabolites uniquely placental estriol synthesis (1-6). Estriol is a hormone unique to prominent in the fetal compartment, by the adaptation of several pregnancy; it is not secreted by the ovary of nonpregnant women. fetal endocrine systems to special intrauterine functions, and by There is evidence that placental chorionic gonadotropin mechanisms to neutralize the biological actions of several potent (hCG) is an important stimulus to fetal adrenal function early hormones critical for normal postnatal development (Table I). in pregnancy; fetal pituitary adrenocorticotropin (ACTH) is es- The following discussion is intended to provide a brief perspective sential for maintenance of fetal zone function by midgestation of this unique environment. (4, 5, 7). Other pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC)-derived pep- tides-alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone (a-MSH), cor- Fetal endocrine adaptations ticotropin-like intermediate peptide (CLIP), and f,-endorphin- In several instances, fetal endocrine systems or hormones have seem to have only limited roles (4, 5). -

Vitamin D, Parathyroid Hormone and the Metabolic Syndrome in Middle

European Journal of Endocrinology (2009) 161 947–954 ISSN 0804-4643 CLINICAL STUDY Vitamin D, parathyroid hormone and the metabolic syndrome in middle-aged and older European men David M Lee, Martin K Rutter1, Terence W O’Neill, Steven Boonen2, Dirk Vanderschueren3, Roger Bouillon4, Gyorgy Bartfai5, Felipe F Casanueva6,7, Joseph D Finn, Gianni Forti8, Aleksander Giwercman9, Thang S Han10, Ilpo T Huhtaniemi11, Krzysztof Kula12, Michael E J Lean13, Neil Pendleton14, Margus Punab15, Alan J Silman, Frederick C W Wu16 and the European Male Ageing Study Group ARC Epidemiology Unit, The University of Manchester, Manchester M13 9PT, UK, 1Manchester Diabetes Centre, The University of Manchester, Manchester, UK, 2Division of Gerontology and Geriatrics and Centre for Musculoskeletal Research, Department of Experimental Medicine, 3Department of Andrology and Endocrinology and 4Department of Experimental Medicine, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Leuven, Belgium, 5Department of Obstetrics, Gynaecology and Andrology, Albert Szent-Gyorgy Medical University, Szeged, Hungary, 6Department of Medicine, Santiago de Compostela University, Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Santiago (CHUS), Santiago de Compostela, Spain, 7CIBER de Fisiopatologı´a Obesidad y Nutricio´n (CB06/03), Instituto Salud Carlos III, Santiago de Compostela, Spain, 8Andrology Unit, Department of Clinical Physiopathology, University of Florence, Florence, Italy, 9Reproductive Medicine Centre, Malmo¨ University Hospital, University of Lund, Malmo¨, Sweden, 10Department of Endocrinology, -

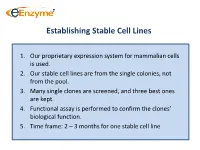

Establishing Stable Cell Lines

Establishing Stable Cell Lines 1. Our proprietary expression system for mammalian cells is used. 2. Our stable cell lines are from the single colonies, not from the pool. 3. Many single clones are screened, and three best ones are kept. 4. Functional assay is performed to confirm the clones’ biological function. 5. Time frame: 2 – 3 months for one stable cell line List of In-Stock ACTOne GPCR Stable Clones Transduced Gi-coupled receptors (22) Transduced Gs coupled receptors (34) Cannabinoid receptor 1 (CB1) Vasoactive Intestinal Peptide Receptor 2 (VIPR2) Dopamine Receptor 2 (DRD2) Melanocortin 4 Receptor (MC4R) Melanocortin 5 Receptor (MC5R) Somatostatin Receptor 5 (SSTR5) Parathyroid Hormone Receptor 1 (PTHR1) Adenosine A1 Receptor (ADORA1) Glucagon Receptor (GCGR) Chemokine (C-C motif) receptor 5 (CCR5) Dopamine Receptor 1 (DRD1) Melanin-concentrating Hormone Receptor 1 (MCHR1) Prostaglandin E Receptor 4 (EP4) Vasoactive Intestinal Peptide Receptor 1 (VIPR1) Cannabinoid receptor 2 (CB2) Gastric Inhibitor Peptide Receptor (GIPR) Glutamate receptor, metabotropic 8 (GRM8) Dopamine Receptor 5 (DRD5) Opioid receptor, kappa 1 (OPRK1) Parathyroid Hormone Receptor 2 (PTHR2) Adenosine A3 receptor (ADORA3) 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) receptor 6 (HTR4) Corticotropin Releasing Hormone Receptor 2 (CRHR2) Glutamate receptor, metabotropic 8 (GRM8) Adenylate Cyclase Activating Polypeptide 1 Receptor type I (ADCYAP1R1) Neuropeptide Y Receptor Y1 (NPY1R) Secretin Receptor (SCTR) Neuropeptide Y Receptor Y2 (NPY2R) Follicle -

Overview of the Endocrine System and Agents Sherrill J

CHAPTER 7 Overview of the Endocrine System and Agents Sherrill J. Brown, DVM, PharmD, BCPS | Kendra Keeley Procacci, PharmD, BCPS, AE–C | Katherine S. Hale, PharmD, BCPS LEARNING OBJECTIVES KEY TERMS AND DEFINITIONS After completing this chapter, you should be able to Acromegaly — overproduction of growth hormone. 1. Describe the negative feedback system used to regulate levels of many of the body’s Feedback system — method of hormones regulation of hormone levels where the 2. Defi ne the following: target hormone affects the production of the stimulating hormone, either PART ● Acromegaly negatively (inhibits production) or ● Hyperparathyroidism positively (stimulates production). 3 ● Hyperthyroidism Hyperparathyroidism — ● Hypoparathyroidism overactive parathyroid glands, ● Hypopituitarism classifi ed as primary, secondary, or tertiary depending on cause of ● Hypothyroidism parathyroid hyperactivity and the 3. State the brand and generic names of the most widely prescribed medications for presence of hyper- or hypocalcemia. pituitary disorders, thyroid disorders, and parathyroid disorders Hypoparathyroidism — a 4. Be familiar with their routes of administration and dosage forms, and the most disorder related to inadequate secretion of parathyroid hormone by common adverse effects of medications used to treat pituitary disorders, thyroid the parathyroid glands resulting in disorders, and parathyroid disorders abnormally low levels of calcium in 5. Describe the therapeutic effects of medications used to treat pituitary disorders, the blood. thyroid disorders, and parathyroid disorders Hypopituitarism — defi ciency of pituitary hormones. Hypothyroidism — a condition which the body does not produce he endocrine system consists of glands located throughout the body, which enough thyroid hormone. T release hormones into the blood. Hormones are chemicals released from Osteomalacia — bone disease one cell in the body that affect other cells in other parts of the body. -

Research Article Interactions Between Serum Adipokines and Osteocalcin in Older Patients with Hip Fracture

Hindawi Publishing Corporation International Journal of Endocrinology Volume 2012, Article ID 684323, 11 pages doi:10.1155/2012/684323 Research Article Interactions between Serum Adipokines and Osteocalcin in Older Patients with Hip Fracture Alexander Fisher,1, 2 Wichat Srikusalanukul,1, 2 Michael Davis,1, 2 and Paul Smith2, 3 1 Department of Geriatric Medicine, The Canberra Hospital, Canberra, P.O. Box 11, Woden, ACT 2606, Australia 2 Australian National University Medical School Canberra, Canberra, ACT 0200, Australia 3 Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, The Canberra Hospital, P.O. Box 11, Woden, ACT 2606, Australia Correspondence should be addressed to Alexander Fisher, alex.fi[email protected] Received 28 October 2011; Accepted 17 December 2011 Academic Editor: Huan Cai Copyright © 2012 Alexander Fisher et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Introduction. Experiments on genetically modified animals have discovered a complex cross-regulation between adipokines (leptin, adiponectin) and osteocalcin. The relationships between these molecules in human osteoporosis are still unclear. We evaluated the hypothesis of a bidirectional link between adipokines and osteocalcin. Materials and Methods. In a cross-sectional study of 294 older patients with osteoporotic hip fracture, we estimated serum concentrations of leptin, adiponectin, resistin, osteocalcin, parameters of mineral metabolism, and renal function. Results. After adjustment for multiple potential confounders, serum osteocalcin concentration was inversely associated with resistin and positively with leptin, leptin/resistin ratio, and adiponectin/resistin ratio. In multivariate regression models, osteocalcin was an independent predictor of serum leptin, resistin, leptin/resistin, and adiponectin/resistin ratios.