HCVF-V3-October 29-2014-Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Barrier Lake Reservoir the Critters of K-Country: Pine Grosbeaks

Is it us, or has this been the strangest of winters, weather-wise? If You Admire the View, You Are a Friend Of Kananaskis In this month's newsletter... Rebuilding Kananaskis Country's Interpretive Trails News from the Board: Creating volunteer opportunities for you Other News: The winter speaker series is back -- and so are the bears, plus a survey opportunity Kananaskis Special Places: Barrier Lake Reservoir The Critters of K-Country: Pine Grosbeaks Rebuilding Kananaskis Country's Interpretive Trails by Nancy Ouimet, Program Coordinator We received fantastic news this week. The Calgary Foundation has approved a $77,000 grant to support our Rebuilding Kananaskis Country’s Interpretive Trails project. In partnership with Alberta Parks, the Friends of Kananaskis Country is working to replace interpretive signage that was damaged or destroyed by the 2013 flood. This is the first phase of a much larger initiative to refresh all interpretive trail signage; currently there are 32 official interpretive trails, and we are targeting refreshing 3 trails per year. The goal of this project is to foster a relationship between the visitor, the natural environment, and the flood affected area. This project will enhance visitor’s knowledge, thus positively influencing their awareness and understanding about the natural aspects of the site. More specifically, it will provide an opportunity to share the unique story of the 2013 flood, outline the environmental impacts at various natural sites, and highlight the community’s support and involvement in rebuilding Kananaskis Country. We are adopting an approach of fewer, but more engaging and effective, interpretive signs (4-6 signs) to reduce distractions and allow the site to speak for itself. -

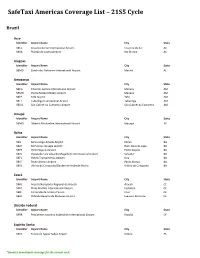

Safetaxi Americas Coverage List – 21S5 Cycle

SafeTaxi Americas Coverage List – 21S5 Cycle Brazil Acre Identifier Airport Name City State SBCZ Cruzeiro do Sul International Airport Cruzeiro do Sul AC SBRB Plácido de Castro Airport Rio Branco AC Alagoas Identifier Airport Name City State SBMO Zumbi dos Palmares International Airport Maceió AL Amazonas Identifier Airport Name City State SBEG Eduardo Gomes International Airport Manaus AM SBMN Ponta Pelada Military Airport Manaus AM SBTF Tefé Airport Tefé AM SBTT Tabatinga International Airport Tabatinga AM SBUA São Gabriel da Cachoeira Airport São Gabriel da Cachoeira AM Amapá Identifier Airport Name City State SBMQ Alberto Alcolumbre International Airport Macapá AP Bahia Identifier Airport Name City State SBIL Bahia-Jorge Amado Airport Ilhéus BA SBLP Bom Jesus da Lapa Airport Bom Jesus da Lapa BA SBPS Porto Seguro Airport Porto Seguro BA SBSV Deputado Luís Eduardo Magalhães International Airport Salvador BA SBTC Hotéis Transamérica Airport Una BA SBUF Paulo Afonso Airport Paulo Afonso BA SBVC Vitória da Conquista/Glauber de Andrade Rocha Vitória da Conquista BA Ceará Identifier Airport Name City State SBAC Aracati/Aeroporto Regional de Aracati Aracati CE SBFZ Pinto Martins International Airport Fortaleza CE SBJE Comandante Ariston Pessoa Cruz CE SBJU Orlando Bezerra de Menezes Airport Juazeiro do Norte CE Distrito Federal Identifier Airport Name City State SBBR Presidente Juscelino Kubitschek International Airport Brasília DF Espírito Santo Identifier Airport Name City State SBVT Eurico de Aguiar Salles Airport Vitória ES *Denotes -

Integrated Access Management

Bow River Water Management Project Richard Phillips On Behalf of The Bow River Water Management Project Advisory Committee 2016 Alberta Irrigation Projects Association Conference Flood and Drought Mitigation: Purpose and Principles Flooding and Drought cannot be prevented, but we can be better prepared • Preparedness, protection and resilience – Reduce risk • Assess, select, coordinate and implement mitigation measures and policies • Evaluate based on: – Understanding causes, risks and impacts – Social, environmental and economic cost-benefit analysis Watershed Management: A Systems Approach • Each river basin is a system • Focus on river basins where flooding and drought risks are highest • Implement best combination of upstream, local, individual and policy-based mitigation measures to protect against flooding events • Enhance the ability to protect against drought Background • The Bow River Working Group, a technical collaboration of water managers and users, was informally established in 2010. • In late 2013 and early 2014 they worked together to identify and assess flood mitigation options in the Bow Basin. Their March 2014 Bow Basin Flood Mitigation and Watershed Management Project report put forward the most promising mitigation options including a number of operational changes for the TransAlta facilities in the upper Bow system. • A separate report conducted by Amec Foster Wheeler in 2015 for Alberta Environment and Parks identified 11 potential flood storage schemes for the Bow River. • This 2016 project is a continuation of both of these prior studies. Vision and Mandate Vision: To have a robust, strategic plan for water management in the Bow River Basin, from the headwaters to the confluence with the Oldman River and continuing through Medicine Hat. -

Little Red Deer Subwatershed Red Deer River State of the Watershed Report 4.4 Little Red Deer River Subwatershed

Little Red Deer Subwatershed Red Deer River State of the Watershed Report 4.4 Little Red Deer River Subwatershed 4.4.1 Watershed Characteristics The Little Red Deer River subwatershed encompasses about 397,166 ha and is located in the Counties of Mountain View and Red Deer and the Municipal Districts of Bighorn No. 8 and Rocky View No. 44 (Figure 112). The Little Red Deer River subwatershed is located south of Gleniffer Lake Reservoir and east of the upper reaches of the Red Deer River. The subwatershed lies in the Subalpine, Upper and Lower Foothills, Foothills Parkland, Dry Mixedwood and Central Parkland Subregions (Figure 113). Soils vary widely, reflecting the great diversity in parent materials and ecological conditions. The vegetation consist of lodgepole pine (P. contorta), Engelmann spruce (P. engelmannii), subalpine fir (A. lasiocarpa) and whitebark pine (P. albicaulis). High elevation grasslands also occur in the Subalpine Subregion. The Upper Foothills Subregion occurs on strongly rolling topography along the eastern edge of the Rocky Mountains. Upland forests are nearly all coniferous and dominated by white spruce (P. glauca), black spruce (P. mariana), lodgepole pine (P. contorta) and subalpine fir (A. lasiocarpa). The Lower Foothills Subregion is dominated by mixed forests of white spruce (P. glauca), black spruce (P. mariana), lodgepole pine (P. contorta), balsam fir (A. balsamea), aspen (Populus spp.), balsam poplar (P. balsamifera) and paper birch (B. papyrifera). The Foothills Parkland is dominated by aspen (Populus spp.), balsam poplar (P. balsamifera) and Bebb willow (S. bebbiana), with a lush understory dominated by a variety of herbaceous plants. Forests in the Dry Mixedwood Subregion are dominated by aspen (Populus spp.), balsam poplar (P. -

Springbank Off-Stream Reservoir Project

Springbank Off-Stream Reservoir Project Canada Environmental Assessment Act, 2012 Project Description April 18, 2016 Prepared for: Alberta Transportation Prepared by: Stantec Consulting Ltd. SPRINGBANK OFF-STREAM RESERVOIR PROJECT CANADA ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT ACT, 2012 PROJECT DESCRIPTION Table of Contents ABBREVIATIONS ............................................................................................................................ I GLOSSARY .................................................................................................................................... II 1.0 GENERAL INFORMATION AND CONTACT(S) .............................................................. 1.1 1.1 NATURE AND PROPOSED LOCATION OF PROJECT ..................................................... 1.1 1.2 PROPONENT CONTACT INFORMATION ......................................................................... 1.4 1.3 LIST OF JURISDICTIONS AND OTHER PARTIES CONSULTED .......................................... 1.5 1.4 OTHER RELEVANT INFORMATION .................................................................................... 1.7 1.4.1 Environmental Assessment and Regulatory Requirements of Other Jurisdictions .......................................................................................... 1.7 1.4.2 Regional Environmental Studies ................................................................ 1.10 2.0 PROJECT INFORMATION ............................................................................................... 2.1 2.1 PROPOSED DEVELOPMENT -

RURAL ECONOMY Ciecnmiiuationofsiishiaig Activity Uthern All

RURAL ECONOMY ciEcnmiIuationofsIishiaig Activity uthern All W Adamowicz, P. BoxaIl, D. Watson and T PLtcrs I I Project Report 92-01 PROJECT REPORT Departmnt of Rural [conom F It R \ ,r u1tur o A Socio-Economic Evaluation of Sportsfishing Activity in Southern Alberta W. Adamowicz, P. Boxall, D. Watson and T. Peters Project Report 92-01 The authors are Associate Professor, Department of Rural Economy, University of Alberta, Edmonton; Forest Economist, Forestry Canada, Edmonton; Research Associate, Department of Rural Economy, University of Alberta, Edmonton and Research Associate, Department of Rural Economy, University of Alberta, Edmonton. A Socio-Economic Evaluation of Sportsfishing Activity in Southern Alberta Interim Project Report INTROI)UCTION Recreational fishing is one of the most important recreational activities in Alberta. The report on Sports Fishing in Alberta, 1985, states that over 340,000 angling licences were purchased in the province and the total population of anglers exceeded 430,000. Approximately 5.4 million angler days were spent in Alberta and over $130 million was spent on fishing related activities. Clearly, sportsfishing is an important recreational activity and the fishery resource is the source of significant social benefits. A National Angler Survey is conducted every five years. However, the results of this survey are broad and aggregate in nature insofar that they do not address issues about specific sites. It is the purpose of this study to examine in detail the characteristics of anglers, and angling site choices, in the Southern region of Alberta. Fish and Wildlife agencies have collected considerable amounts of bio-physical information on fish habitat, water quality, biology and ecology. -

Water Storage Opportunities in the South Saskatchewan River Basin in Alberta

Water Storage Opportunities in the South Saskatchewan River Basin in Alberta Submitted to: Submitted by: SSRB Water Storage Opportunities AMEC Environment & Infrastructure, Steering Committee a Division of AMEC Americas Limited Lethbridge, Alberta Lethbridge, Alberta 2014 amec.com WATER STORAGE OPPORTUNITIES IN THE SOUTH SASKATCHEWAN RIVER BASIN IN ALBERTA Submitted to: SSRB Water Storage Opportunities Steering Committee Lethbridge, Alberta Submitted by: AMEC Environment & Infrastructure Lethbridge, Alberta July 2014 CW2154 SSRB Water Storage Opportunities Steering Committee Water Storage Opportunities in the South Saskatchewan River Basin Lethbridge, Alberta July 2014 Executive Summary Water supply in the South Saskatchewan River Basin (SSRB) in Alberta is naturally subject to highly variable flows. Capture and controlled release of surface water runoff is critical in the management of the available water supply. In addition to supply constraints, expanding population, accelerating economic growth and climate change impacts add additional challenges to managing our limited water supply. The South Saskatchewan River Basin in Alberta Water Supply Study (AMEC, 2009) identified re-management of existing reservoirs and the development of additional water storage sites as potential solutions to reduce the risk of water shortages for junior license holders and the aquatic environment. Modelling done as part of that study indicated that surplus water may be available and storage development may reduce deficits. This study is a follow up on the major conclusions of the South Saskatchewan River Basin in Alberta Water Supply Study (AMEC, 2009). It addresses the provincial Water for Life goal of “reliable, quality water supplies for a sustainable economy” while respecting interprovincial and international apportionment agreements and other legislative requirements. -

Bow River Basin State of the Watershed Summary 2010 Bow River Basin Council Calgary Water Centre Mail Code #333 P.O

30% SW-COC-002397 Bow River Basin State of the Watershed Summary 2010 Bow River Basin Council Calgary Water Centre Mail Code #333 P.O. Box 2100 Station M Calgary, AB Canada T2P 2M5 Street Address: 625 - 25th Ave S.E. Bow River Basin Council Mark Bennett, B.Sc., MPA Executive Director tel: 403.268.4596 fax: 403.254.6931 email: [email protected] Mike Murray, B.Sc. Program Manager tel: 403.268.4597 fax: 403.268.6931 email: [email protected] www.brbc.ab.ca Table of Contents INTRODUCTION 2 Overview 4 Basin History 6 What is a Watershed? 7 Flora and Fauna 10 State of the Watershed OUR SUB-BASINS 12 Upper Bow River 14 Kananaskis River 16 Ghost River 18 Seebe to Bearspaw 20 Jumpingpound Creek 22 Bearspaw to WID 24 Elbow River 26 Nose Creek 28 WID to Highwood 30 Fish Creek 32 Highwood to Carseland 34 Highwood River 36 Sheep River 38 Carseland to Bassano 40 Bassano to Oldman River CONCLUSION 42 Summary 44 Acknowledgements 1 Overview WELCOME! This State of the Watershed: Summary Booklet OVERVIEW OF THE BOW RIVER BASIN LET’S TAKE A CLOSER LOOK... THE WATER TOWERS was created by the Bow River Basin Council as a companion to The mountainous headwaters of the Bow our new Web-based State of the Watershed (WSOW) tool. This Comprising about 25,000 square kilometres, the Bow River basin The Bow River is approximately 645 kilometres in length. It begins at Bow Lake, at an River basin are often described as the booklet and the WSOW tool is intended to help water managers covers more than 4% of Alberta, and about 23% of the South elevation of 1,920 metres above sea level, then drops 1,180 metres before joining with the water towers of the watershed. -

Monitoring the Elbow River

Freshwater Monitoring: A Case Study An educational field study for Grade 8 and 9 students Fall 2010 Acknowledgements The development of this field study program was made possible through a partnership between Alberta Tourism, Parks and Recreation, the Friends of Kananaskis Country, and the Elbow River Watershed Partnership. The program was written and compiled by the Environmental Education Program in Kananaskis Country and the field study equipment and programming staff were made possible through the Friends of Kananaskis Country with financial support from the Elbow River Watershed Partnership, Alberta Ecotrust, the City of Calgary, and Lafarge Canada. The Elbow River Watershed Partnership also provided technical support and expertise. These materials are copyrighted and are the property of Alberta Tourism, Parks and Recreation. They have been developed for educational purposes. Reproduction of student worksheets by school and other non-profit organizations is encouraged with acknowledgement of source when they are used in conjunction with this field study program. Otherwise, written permission is required for the reproduction or use of anything contained in this document. For further information contact the Environmental Education Program in Kananaskis Country. Committee responsible for implementing the program includes: Monique Dietrich Elbow River Watershed Partnership, Calgary, Alberta Jennifer Janzen Springbank High School, Springbank, Alberta Mike Tyler Woodman Junior High School, Calgary, Alberta Janice Poleschuk St. Jean Brebeuf -

Het Is Mij Opgevallen Dat Heel Veel Eerste Keer Canada Reizigers, of Ze

Het is mij opgevallen dat heel veel eerste keer Canada reizigers, of ze nu zelf alles boeken of een via georganiseerde reis, een overvol schema hebben en het zwaartepunt op het zoveel mogelijk locaties aandoen en veel kilometers rijden ligt en daardoor veel moois missen. Soms realiseren de bezoekers zich niet dat je er niet hard zult rijden dus langer over je afstand doet. Vooral de camperrijder onderschat de afstanden nog wel eens en daar is de reisorganisatie medeschuldig aan want die zegt tuurlijk kan je deze reis maken want je kan makkelijke 500 kilometer op een dag rijden waarmee ze voorbijgaan aan de bezienswaardigheden. Daar komt ook bij dat sommige geen idee hebben hoe druk het tegenwoordig is in de maanden juli/augustus en ook september nog. En liever het motto vrijheid blijheid willen volgen en dat is heel begrijpelijk maar even zo maar een plek voor je camper/tent/hotel vind je niet meer in deze periodes en is het handig om zeker in de Nationale Parken een reservering te maken. Ook verdiepen mensen zich niet echt in het voor en na seizoen, want zeker in mei kan er nog heel veel gesloten zijn zoals campings, sommige accomodaties gaan pas tegen het einde van mei open en excursie beginnen ook pas tegen het einde van deze maand. Bv bij Jasper gaan de Maligne Lake Cruises naar Spirit Island pas op 25 mei beginnen en kan er nog ijs op het meer liggen maar daarentegen is de Jasper Tramway al open sinds 22 maart maar de top van Whistler Mountain zal zeker nog deels met sneeuw bedekt zijn. -

Filed Electronically March 3, 2020 Canada Energy Regulator Suite

450 – 1 Street SW Calgary, Alberta T2P 5H1 Tel: (403) 920-5198 Fax: (403) 920-2347 Email: [email protected] March 3, 2020 Filed Electronically Canada Energy Regulator Suite 210, 517 Tenth Avenue SW Calgary, AB T2R 0A8 Attention: Ms. L. George, Secretary of the Commission Dear Ms. George: Re: NOVA Gas Transmission Ltd. (NGTL) NGTL West Path Delivery 2022 (Project) Project Notification In accordance with the Canada Energy Regulator (CER)1 Interim Filing Guidance and Early Engagement Guide, attached is the Project Notification for the Project. If the CER requires additional information with respect to this filing, please contact me by phone at (403) 920-5198 or by email at [email protected]. Yours truly, NOVA Gas Transmission Ltd. Original signed by David Yee Regulatory Project Manager Regulatory Facilities, Canadian Natural Gas Pipelines Enclosure 1 For the purposes of this filing, CER refers to the Canada Energy Regulator or Commission, as appropriate. NOVA Gas Transmission Ltd. CER Project Notification NGTL West Path Delivery 2022 Section 214 Application PROJECT NOTIFICATION FORM TO THE CANADA ENERGY REGULATOR PROPOSED PROJECT Company Legal Name: NOVA Gas Transmission Ltd. Project Name: NGTL West Path Delivery 2022 (Project) Expected Application Submission Date: June 1, 2020 COMPANY CONTACT Project Contact: David Yee Email Address: [email protected] Title (optional): Regulatory Project Manager Address: 450 – 1 Street SW Calgary, AB T2P 5H1 Phone: (403) 920-5198 Fax: (403) 920-2347 PROJECT DETAILS The following information provides the proposed location, scope, timing and duration of construction for the Project. The Project consists of three components: The Edson Mainline (ML) Loop No. -

Currents Finds a Brand New Home

Volume 16, No. 2 Spring, 2010 Trout Unlimited Canada’s Currents finds a brand new home Alberta’s Raven River: an example of conservation in action by Phil Rowley he Raven River, a tributary of the threats facing the Raven. The Edmonton The Raven River project was broken Red Deer River, is located in Cen- chapter backed by the Lloyd Shea Fisheries down into four key components. T tral Alberta just west of Red Deer. Enhancement fund looked for additional • Assessment of fish habitat and riparian 1983 saw the completion of the Dickson funding and project partners to begin work (river bank) conditions Dam forming Gleniffer Lake which the on the Raven. • Gaining a measure of the existing brown Raven River now spills into. Flowing over The Lloyd Shea Fisheries Enhancement trout population 102 KM in an easterly direction from the Fund was created in memory of Lloyd Shea, • Assess the relative abundance, diversity slopes of the Rocky Mountains the Raven an ardent fly fisher, hunter, advocate for and distribution of all fish species in the River carries agriculture, forestry and the conservation and founding member of the River oil and gas industry on her shoulders. The Edmonton chapter. In honour of Lloyd’s Photo by Ryan Popowich. Raven is held close to the hearts of local fly memory and legacy Dave Johnston from • Identify critical spawning areas used by fishers as one of Alberta’s premier brown the Fishin’ Hole proposed that the Edmon- brown trout trout fisheries. As with any river system ton chapter establish the fund with their Assessment of existing fish habitat and exposed to human activity the Raven faces assistance, driven by a primary mandate river bank conditions was done both on a number of threats to its health including to conduct studies on brown trout streams foot and through the unique use of a low sedimentation, cattle damage and an over- in central Alberta.